Inside the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Process

MIAMI – Phone call or knock on the door?

The 15 finalists for the 2020 modern era class of the Pro Football Hall of Fame presented their campaign speeches on the field years ago and there was just one thing left for them to do Saturday to join the select group of players, owners, executives, coaches and contributors in Canton.

They had to wait.

The minutes seemed like hours as they anxiously passed time until being told to return to their rooms at the Loews Miami Beach Hotel in mid-afternoon to be available to either receive a phone call or knock on the door.

The call means they are out. Better luck next year. Players have been known to immediately start crying when they are given the bad news.

The knock on the door means they are in. And it comes accompanied by a huge hug from HOF president David Baker—at 6-9, 400 pounds, he only knows huge hugs.

“Welcome to Canton,” he says. “Thank you for all you have done for the game.”

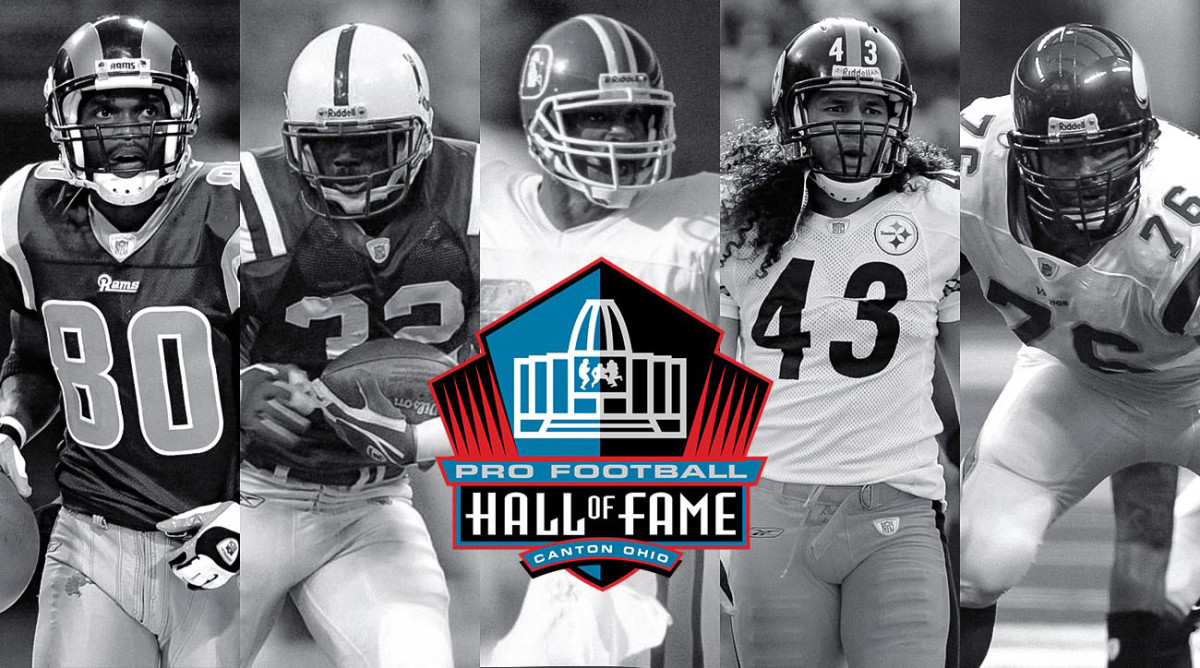

Baker pounded on the doors of Steelers safety Troy Polamalu, Seahawks/Vikings guard Steve Hutchinson, Broncos safety Steve Atwater, Rams receiver Isaac Bruce and Colts running back Edgerrin James on Saturday around 3:15 p.m.

Welcome to the Class of 2020.

Troy Polamlau, Steve Hutchinson, Edgerrin James, Steve Atwater and Isaac Bruce are all headed to the Pro Football Hall of Fame https://t.co/TkGPJ1SIdA pic.twitter.com/6idoHp7N87

— Sports Illustrated (@SInow) February 1, 2020

Polamalu is the only player in his first of year eligibility. The other four had experienced the heartbreak of the phone call more than once.

Along with the 10 seniors, three contributors and two coaches previously selected in Canton on Jan. 8 for the Centennial Class, the HOF is now up to 346 members. How exclusive is this club? In the 100-year history of the NFL, 29,000 men have played the game and there have been 800 players, coaches and officials who have been finalists.

The 48 selectors—I’ve been on the committee for 11 years—convened at 7:30 a.m. in the Cowrie Room on the third floor at the Loews hotel. Usually we meet in the Super Bowl media center, but holding this year’s meeting in the same hotel the players were staying made it easier for Baker to quickly phone the 10 players who failed to pick up the votes and then knock on doors of the five new inductees rather than deal with the brutal Miami traffic.

The Loews was the place to be for autograph seekers. It’s where NFL 100 Players who will be honored Sunday before the kickoff of Super Bowl LIV were staying as well.

We started deliberations at 8 a.m., finished at 2 p.m., and concluded the voting at 2:30 p.m. when the paper ballots with the final vote were handed to a team of accountants from Ernest and Young to tabulate.

Before peeling back the layers of what actually goes on in the meeting room as the selectors “change lives,” as Baker likes to say, let’s enter the Super Bowl hotel room of two men who recently experienced the emotions of selection Saturday.

The Phone Call

Everson Walls, a Cowboys cornerback who led the NFL in interceptions three times and was a three-time All-Pro and later made a Super Bowl XXV game-saving tackle on Thurman Thomas when he played for the Giants, was among the 15 finalists in 2018 for the first time in his 20th and final year of modern era eligibility.

He was a great player, a fearless cover corner, but is best known for getting beat by Dwight Clark on “The Catch,” on Jan. 10, 1982, in the NFC Championship Game, which was the official beginning of the 49ers dynasty in the ‘80s and the beginning of the end of the Tom Landry Era. Clark’s leaping catch with Walls trailing him along the back line of the end zone was voted the No. 2 play in NFL history behind only the Immaculate Reception.

Walls was thrilled to have finally made it to the final 15, even if he did question why it didn’t happen sooner. Bringing the candidates to the Super Bowl site is a relatively new process and makes for great drama, and great television, when Baker knocks on the door. The final 15 are paid $10,000 each to attend a bunch of functions over the weekend, including NFL Honors on Saturday night, when the vote is made public. Even those who didn’t get in are asked to attend.

Early in the afternoon in Minneapolis two years ago, Walls’ wife, daughter and friends left him alone in his room to give him space. He decided to make two phone calls.

The first was to one of his best friends, former 49ers safety Dwight Hicks, who was the veteran teamed with rookies Ronnie Lott, Eric Wright and Carlton Williamson in the Niners secondary in the 1981 playoff game against the Cowboys. Walls and Hicks are as close as brothers.

The second call might surprise you.

Walls called Clark.

They became friendly in 1985 when Clark told him that he and Joe Montana had been paid by Kodak for the famous picture of “The Catch” that was being used in advertisements. Walls was as prominent in the picture as Clark, and Montana wasn’t even in it, but Walls had not been paid a penny. He threatened to sue Kodak and said he settled the case by receiving more money from Kodak than Clark and Montana combined plus a trip to the Super Bowl.

He appreciated Clark telling him about his deal with Kodak and, as a result, they became good friends. They were the Ralph Branca and Bobby Thomson of the NFL. When Clark was diagnosed with ALS in March of 2017, Walls was constantly in touch to check up on him. When the 49ers honored Clark in October of 2017 at halftime of a game at Levi’s Stadium, Walls was the only player from the Cowboys to attend.

As Walls waited and hoped for the knock on the door from Baker, it felt right to spend time talking to Clark.

“We had gotten to know each other really well,” Walls said. “When he started to get sick, we were past the whole adversarial thing. It was about supporting each other. It was really poignant. He was telling me about his experience when Ed DeBartolo was a Hall of Fame finalist (in 2016) and Dwight prayed over his rosaries. He said he would do the same for me. We started talking about family and things we had gone through, trials and tribulations of our past. Our talk had nothing to do with the Hall of Fame.”

Walls’ family and friends were back in the room by mid-afternoon.

“The Hall of Fame told us to close our doors at 3 o’clock,” Walls said. “At 3:33, my phone rings.”

He had to answer it knowing it was not going to be good.

“I was truly just happy to be a part of it, happy to be considered,” Walls said. “I already knew I wasn’t going to make it.”

On June 4, 2018, almost four months after Walls received a call instead of a knock on his door, his friend Dwight Clark passed away. He was just 61 years old.

The Knock On The Door

Kevin Mawae, one of the best centers in NFL history during his 16-year career with the Seahawks, Jets and Titans, was a top 25 semifinalist in 2019 for the sixth time in his sixth year of eligibility and a top 15 finalist for the third year in a row.

He was tired of the phone calls. He wanted Baker to show up at his door.

He was in his hotel room in Atlanta on the day before the Super Bowl last February, just as he had been in Minneapolis the year before and Houston the year before that.

“The waiting is awful,” he said. “Every time the phone rings, you jump.”

It was just Mawae and his wife Tracy waiting together. He did not want 30 people around him. Too much disappointment if he failed to get in again. His friends, at least most of them, knew not to call him as decision time approached. “On draft day you want the phone to ring,” he said. “On this day, you don’t.”

Mawae passed the time playing games on his phone. Just around the time the HOF told all the candidates to be in their rooms, Mawae’s cell phone rang. His heart was racing. He looked at the caller ID. It was one of his best friends.

“Did you get in?” Dino Rizzo asked.

“Bro, what are you calling me for?” Mawae said. “They call if you don’t get in.”

You don’t want friends to call and you don’t want the maid to be knocking asking if you want chocolates on your pillow.

“You don’t want to order room service, either,” Mawae said. “The only knock you want to hear is a big rap by David Baker.”

One of the voters, a Mawae supporter, texted him when the meeting ended and before Baker started making his rounds.

“We did the best we could,” the voter texted.

Mawae was confused. What did that mean? Was he in? Was he out? He was angry about the text.

His mind started playing tricks. He heard knocks on doors down the hall. But was it really his room? He jumped up. Nobody was there. Then there was a booming knock. It was unmistakable. It was his door. No room service person knocks as loud as Baker.

“I just started crying,” Mawae said. “I got lost in the moment for a second.”

He collapsed into Baker’s arms.

His wait was over.

The Process

So, how does the process work?

The original list of modern era candidates is usually about 100. Players and coaches must have been retired five seasons to be eligible and then they are eligible for 20 years. If they have not been elected after 20 years, they become part of the senior pool. The first vote reduces the list to 25. The next vote takes it down to 15.

The final 15 make it into what’s called “The Room,” meaning their candidacy will be debated on Super Bowl Saturday. The HOF picks a media member from the city where the player spent the majority of his career to make a presentation, which sets the tone for the discussion. Then any of the other 47 selectors can request the microphone and speak up in support or against a candidate. Some conversations last 10 minutes. Some go 45-60 minutes.

The list of 15 is then sliced to 10 in the first reduction vote of the day. Additional comments are solicited but rarely offered. Then the list is voted down to five. In every other year, once a candidate makes the final five, he needs 80% approval to be selected. That means 10 no votes can knock him out. At this stage, the candidates are not competing against each other. The voting is considered a formality.

There was a change to the voting procedure this year. A Blue Ribbon panel convened in Canton on Jan. 8 to select 10 seniors, three contributors and two coaches to be part of the Centennial Class of 2020. Once the list was narrowed to those 15, there was not an 80% vote. Nor was there an 80% vote Saturday on the final five modern era candidates.

Why the shift in policy?

The HOF wanted 20 enshrinees: 20 for 2020. Instead of taking a chance that any of the 15 picked in Canton would be rejected, the 80% vote was eliminated. The same reasoning was applied Saturday to the five modern era finalists. Once they made it to the final five, they were in.

Terrell Owens, big surprise, was the most controversial candidate of the 21st century. He had the statistical credentials, but the HOF made a ruling that the locker room can be considered an extension of the playing field.

So a player such as Owens, generally considered a quarterback killer and locker room cancer, was the subject of an hour-long discussion in his first year of eligibility. He didn’t make the cut to 10. The second year there was another hour spent on Owens and again he didn’t make the cut to 10.

The third time was the lucky charm for T.O. in 2018. It took another hour of deliberation, but this time he made the cut to 10 and then the cut to five, received the 80% final vote, and true to form, became the first living HOFer not to show up for the induction ceremony in Canton. Owens decided to “love me some me” and celebrate instead in Chattanooga, where he went to college.

It’s always fascinating to observe the dynamics in the meeting room. Some of the voters are quiet and have often been referred to as “silent assassins.” You don’t know what they are thinking.

The tables are placed in a horseshoe type setup for the selectors with Baker and HOF executives seated in a row of tables across the front. The panel consists of 46 media members and HOFers James Lofton and Dan Fouts, who are analysts for CBS.

Peter King of NBC Sports, and formerly of Sports Illustrated, is among the most talkative of the selectors. He speaks up at least once on each candidate, and often goes back for a second helping. But his perspective and insight are valuable.

Dan Pompei of The Athletic is among the smartest guys in the room. Thoughtful and informed. Not everybody is. One pro-Owens supporter actually said in the year he was voted in that he felt one of T.O.’s HOF credentials was his colorful style of play, which translated well on the Madden video game, which he attributed to hooking him and others of his generation on the NFL.

Well, that was a ridiculous argument. No names. I’m trying to be transparent, but don’t want to embarrass the voter by giving him up.

Long-time NFL writer Jason Cole annually conducts a poll of his sources asking them for their top five candidates once the final 15 is set. This year, he polled 330 people. Barry Wilner of the Associated Press, whom I have known since we worked together on my first job at the AP after graduating from Syracuse University in 1976, always raises key issues.

The ballot this year was top heavy with four safeties (Polamalu, John Lynch, Atwater and LeRoy Butler), wide receivers (Bruce, Torry Holt and Reggie Wayne) and offensive linemen (Alan Faneca, Hutchison, Tony Boselli). The candidates also included Sam Mills, Richard Seymour, James, Bryant Young and Zach Thomas.

My ballot on the cutdown to 10: Atwater, Bruce, Faneca, Hutchinson, James, Lynch, Mills, Polamalu, Seymour and Thomas.

My ballot on the cutdown to five: Bruce, Faneca, Hutchinson, Lynch, Polamalu. My batting average wasn’t so good. My final vote included just three out of five. Going into the meeting, Polamalu was the only certainty. Hutchison and Faneca were so close I voted for both.

I was also part of the 25-member Blue Ribbon panel that selected the seniors, contributors and coaches last month. The committee was comprised of 13 voters from the 48 regular selectors, seven Hall of Famers and five historians, including Patriots coach Bill Belichick. I sat next to him for the more than 10-hour meeting and I saw the very personable side of him that he rarely shows in his press conferences.

He helped educate me on the players from the 1920s, 30s and 40s and I helped educate him on the HOF process. He was studying film on the seniors right up until the meeting started at 8 a.m. Is anybody surprised?

The toughest decisions in January were in the coaching category. I voted for Jimmy Johnson and Bill Cowher, who both got in. Dick Vermeil and Mike Holmgren and Dan Reeves were also deserving. Faneca’s chances Saturday were likely hurt by the previous selection at the January meeting of Cowher and safety Donnie Shell as a senior and Polamalu’s presence. There might have been a reluctance from the voters to have four Steelers among the 20 inductees.

My biggest disappointment was the exclusion of Cowboys receiver Drew Pearson, who was No. 1 on my seniors list along with Jets tackle Winston Hill. I was most happy that former Giants general manager George Young was finally selected as a contributor, but so sad that he passed away in 2001.

The committee will reconvene in Tampa Bay next year on Feb. 6, the day before Super Bowl LV, to pick the class of 2021. One spot is already taken. Peyton Manning is eligible for the first time.

The new Hall of Famers received the knock from Baker and then gathered Saturday at 4 p.m. in a third floor lobby of the Loews to congratulate each other and follow Baker on the bus to NFL Honors. Hutchison was so relieved. He knew when he heard the rapping on his door that Baker was on the other side. “Loud knock,” he said.

Two years ago on a freezing cold night in Minneapolis, the bus to NFL Honors was filled with the players who had received the phone call instead of the knock. The windows were fogged up. Walls was the last one on the bus. The players were distraught. No one likes rejection. Walls took one look at the moisture on the windows and came to an inescapable conclusion.

“The bus was crying,” he said.

He was probably right.

More on the Pro Football Hall of Fame:

• Seahawks Legend Steve Hutchinson Elected into Pro Football Hall of Fame