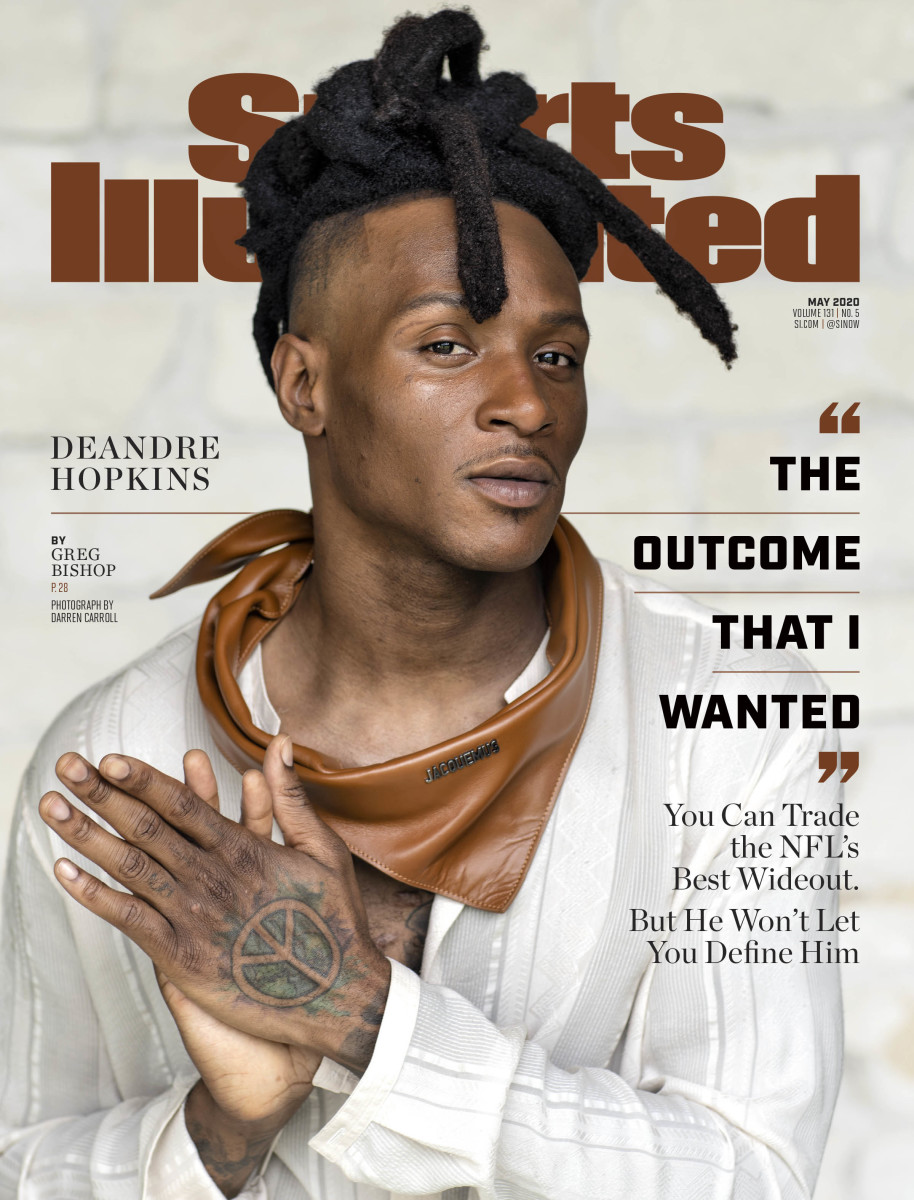

DeAndre Hopkins Will Define Himself and His Future

As the Texans shot to a 24–0 lead over the Chiefs in the AFC Divisional Playoff Round, wideout DeAndre Hopkins stalked the sideline. Do not get complacent, he warned teammates, knowing that Patrick Mahomes would continue to sling passes, that Kansas City entered the game as Super Bowl favorites.

Then, a football apocalypse. The wild scores, the wilder bounces, the disastrous fourth-down playcall, the countless “this game is drunk” tweets and, of course, the Chiefs’ epic comeback. But that’s not what Hopkins will remember about that afternoon. He’ll remember the shot he took to the midsection in the second quarter, the one that took his breath away, that required X-rays at halftime, that tore cartilage in his ribs. He’ll remember jogging back on the field, only to dislocate his right index finger early into the third quarter. “I didn’t care,” Hopkins says. “I popped it right back into place and kept going.” His final tally: nine receptions, 118 yards and two injuries for a man who describes himself as both the toughest player—having missed only two games, both meaningless regular-season finales, in seven seasons—and the best receiver in the NFL.

Despite the gut-wrenching loss, last season seemed to mark more of a beginning for Houston than an end. In his third year, Deshaun Watson had solidified himself as a franchise quarterback, developing a telepathic connection with his favorite target and fellow Clemson alum. Hopkins and Watson could draw up plays in the huddle, sandlot style, like for the two touchdowns they connected on to beat the Colts. Or they could adjust, mid-route, without even a hand gesture, as they did on deep balls against the Saints and Bills. Off the field they often met for dinner, laying out plans for NFL domination, the championships they’d win, the Hall of Fame careers they’d carve out. When Hopkins’s confidant Michael Irvin watched the duo interact, they reminded him of himself and Emmitt Smith—before they won three championships with the Cowboys. In other words, the Texans stood on the precipice of greatness.

As Hopkins, 27, sat down at his locker after the game, surrounded by silence and his teammates, he had two thoughts: that the Texans had given their long-suffering fan base a future to look forward to and that they would need to end their string of playoff disappointments without him. The wideout had spoken to his family throughout the season about his desire to start over, with a new team, and, more specifically, with a new boss. He believed that Bill O’Brien, the lone NFL coach to also hold a general manager title, had been shopping him for more than a year.

To the rest of a football-obsessed world, the idea that any team would unload an elite player in his prime—let alone one who had never carried a diva label, proposed to a kicking net or ripped his quarterback (even with the uncertainty under center that preceded Watson)—seemed ludicrous. But the trade that shocked the rest of the NFL came as no surprise to Hopkins.

That January afternoon at Arrowhead Stadium he tugged off his jersey, met with reporters and crisscrossed the corridors until he found his mother, Sabrina Greenlee. “We talked about this before the year,” she told him. “I know you guys had success as a team and you got further than in the past. But if you’re ready to go, I will be your No. 1 supporter.”

Anyone who knew Hopkins, his story and his relationship with O’Brien would understand, he thought. At that point, though, few did. His Houston tenure was over, despite the teammates he loved, the quarterback he bonded with and the city that had become his adopted home. What Hopkins knew was, “that asking for a little raise would lead to the outcome that I got,” he says, “which is the outcome that I wanted.”

* * *

The Parallels to Hopkins’s tenure in Houston started back at Clemson, in college, right where he grew up. When Tigers assistant Dabo Swinney took over as head coach in 2008, he was determined to turn around a program that hadn’t won 10 games in a season in nearly two decades. Even though Hopkins stood only 6' 1" and weighed in the neighborhood of 190 pounds, Swinney watched him hang in the air, making leaping, twisting grabs, turning receptions into artwork and games into Cirque du Soleil performances. Swinney knew he’d found a pillar for his resurgence, a receiver who, the coach says, “when he’s covered, he’s wide open, and when he’s double-covered, he’s still open.”

At the end of Hopkins’s junior season, he faced an LSU defense stocked with future pros in the Peach Bowl. Late in the fourth quarter Clemson trailed by two and, with its offense backed way up, faced a fourth-and-16 with 1:22 remaining. Quarterback Tajh Boyd threw a sinking liner toward Hopkins, who managed, while sliding, to grab it for a 26-yard gain, keeping alive the game-winning drive. Clemson would become a national power and play in four of the last five national championship games, claiming two titles. “That play helped us take the next step,” Swinney says. When Hopkins returned to campus this spring, his old coach told him “there’s no 44–16”—the score by which Clemson defeated Alabama to win the 2018 championship—“without fourth-and-16.”

Hopkins took his own next steps, declaring for the draft, going 27th to Houston, instantly making pro defenders look as silly as overmatched college corners. Irvin noticed Hopkins’s greatest strength, what has always separated him: his Hall of Fame body control. Hopkins is what Irvin calls “an area-code guy,” meaning he caught every ball thrown in his general vicinity. Most receivers with that kind of body control—Irvin points to Cris Carter—cannot match Hopkins’s speed. “That is the most important asset a wide receiver can have,” Irvin says.

Hopkins wonders whether being bow-legged as a child forced him to adapt in ways that improved his balance. But those adjustments were far easier than his life off of the field. Growing up in poverty, with four siblings; watching his mother go blind after another woman threw acid in her face in a fit of jealous rage over a man both had been dating; seeing her work multiple jobs, then learn to live without her sight; knowing that both his parents sold drugs; the death of his father when DeAndre was six months old—all that shaped Hopkins’s mindset beyond his skill set. Deal with the pain. People you love can make mistakes. Move forward.

And—big and—in seven seasons, Hopkins has staked his claim as the NFL’s top wideout. He has surpassed 1,100 receiving yards five times and caught 54 touchdown passes while becoming the second-youngest receiver to amass 600 receptions and finishing 2018 with career highs in catches (115) and yards (1,572). Last season Hopkins became only the fourth receiver since 2000—along with Calvin Johnson, Antonio Brown and Chad Johnson—to be named first-team All-Pro by the Associated Press for at least three straight years. But he never did complete the college parallel, never delivered that signature postseason win.

All that set the stage for the shock from outsiders that followed the trade. Hopkins wasn’t mildly surprised. He even told friends he had a hunch he would be sent to the Cardinals, and in mid-March, his premonition came true. O’Brien swapped him and this year’s fourth-round pick for running back David Johnson, a second-round selection (2020) and a fourth-rounder (’21). Irvin reacted like everyone else. “I didn’t understand it,” he says. “DeAndre can box people out, he can climb over you, take the ball off the top of your head, go down and grab it off a blade of grass. That’s the greatest asset a young, mobile quarterback can have. That’s why my mind went boof! on this whole trade.”

In the aftermath, two separate but related stories dominated news cycles. One centered on why Hopkins had wanted out. The other disparaged the package Houston received in return. O’Brien told season-ticket holders on a conference call that the move had been made in the best interests of his team, even spelling out T-E-A-M.

* * *

Hopkins took the call from O’Brien while working out with Julio Jones in Los Angeles. Their initial reaction? “We both smiled,” Hopkins says. The coach adopted a businesslike approach for the brief exchange, his tone and message exactly what the receiver had expected, given the tenor of their interactions over the past six seasons. “There was no relationship,” Hopkins says. “Make sure you put that in there. There’s not a lot to speak about.”

Watson, meanwhile, had just finished his own workout with his private quarterbacks coach, Quincy Avery, who saw dozens of messages about the trade when he picked up his phone. Avery told Watson, who thought he was joking. The quarterback ran to grab his own device and sat down immediately, trying to make sense of the news; even he was shocked. “Wow,” Watson said, over and over, before posting a Drake lyric on Twitter, the one that resonated across the NFL: “iconic duos rip and split at the seams.”

Houston framed the move as an unfortunate economic reality. Hopkins had signed a five-year extension in 2017 that guaranteed him $49 million, more than any receiver in the league. But that deal quickly became outdated, and in the three years that remained, none of the money—$12.5 million next season, $13.5 million in ’21 and $13.9 million in ’22—was guaranteed. Hopkins wanted another extension, at or above Jones’s salary with the Falcons (an average of $22 million), especially considering what the Cowboys just paid Amari Cooper ($20 million, on average, for an inferior talent).

The Texans will also soon confront a salary-cap crunch, if, as expected, they commit huge contracts to Watson and left tackle Laremy Tunsil—the latter a practical necessity because of the bounty they dealt to obtain him from the Dolphins eight months ago. Hopkins knew that in the team’s recent history it had only redone one contract with more than two years remaining (receiver Andre Johnson) and only extended one player who had two years left (defensive end J.J. Watt). But wasn’t he the same kind of generational talent?

As Irvin assessed the trade from afar, he continued to feel as if he wasn’t hearing the full story. This divorce, like most divorces but especially sports breakups, couldn’t have been just about money. Every player on every team wants more. So Irvin spoke to Hopkins, who said all the right things, about respecting O’Brien and wanting a new start. But Hopkins also phoned back two days later, and in that call they discussed an earlier meeting with O’Brien that helped explain why he had wanted out. It took place during last season, which was odd because O’Brien and Hopkins had rarely met privately before. Hopkins can’t recall his coach ever asking about his personal life, or expressing concerns about his off-field choices. But in that meeting Hopkins told Irvin that, in reference to Hopkins’s friends, O’Brien brought up another player he had coached, former Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez, the convicted murderer who hanged himself in prison. O’Brien also used the term “baby mothers” to refer to the mothers of Hopkins’s three children, two boys and a girl. (He is not married.) O’Brien confidants say they doubt the coach used those exact words. But because the men lacked depth in their relationship, the sentiments that O’Brien expressed didn’t come across as genuine concerns for Hopkins and his well-being. They seemed like answers to why they had no relationship in the first place. They felt like judgments, from a coach who didn’t seem to care about him—plus the outdated contract.

Hopkins doesn’t deny the meeting but prefers to not delve deeper, saying only, “If I let the judgment of other people dictate the reality of my life, I wouldn’t be in the position I’m in now.” O’Brien, citing a similar desire to avoid a public back-and-forth, declined to comment beyond, “We wish him the very best in Arizona.”

Irvin, as is his nature, doesn’t mind a little delving. He notes that Hopkins has never been arrested, that he counts CEOs and spiritual mentors among his friends and, unless there was something that hasn’t come to light, that his childhood companions had never proved to be an issue. “Listen, every black athlete in the league has friends like [Hopkins does],” Irvin says. “DeAndre should be commended, not criticized, for getting to where he is from where he came from.”

After the second call, the trade at least made some sense to Irvin. It wasn’t just about contract, although it factored in and, by asking to redo it, Hopkins knew he could leverage his way out of town. “I knew it had to be something. Honestly, Coach O’Brien should want this out, to say, This is why I made that decision. I’m not that crazy.” Irvin says with a laugh. “He should be thanking me!”

* * *

* * *

Once Irvin shared the meeting’s contents on ESPN, anonymous sources began to paint a picture of Hopkins as a malcontent who had started to decline. Hopkins believes the sources hoped to tarnish his name and justify a trade that had been widely panned.

The reaction around the league spoke less to why Hopkins left and more to the value Houston received in return, one of three significant missteps—the Tunsil and Hopkins trades, plus the fake punt against the Chiefs—that have called the nature of O’Brien’s tenure into question. In fairness, O’Brien does own a 52–44 record as the Texans coach, complete with four playoff appearances and two postseason victories. It’s his GM performance that’s harder to defend, especially when Buffalo gave up more for Stefon Diggs than Arizona did for Hopkins. “This is why you don’t make your coach your general manager,” wrote one NFC GM in a text message to SI. “Laughable,” an NFC personnel executive told SI, followed by three crying emojis and one animated shoulder shrug. Even in a year when Hopkins’s statistics dipped relative to his high standard of ’18, many around the NFL still seem to see him as a transformative receiver more than they see O’Brien as a capable GM.

Hopkins did address some of the anonymous criticisms with SI. But first, he said, “Obviously, we know where all that’s coming from.”

He didn’t practice often enough. Hopkins says that stems mostly from 2018, when he tore ligaments in his left ankle, requiring tightrope surgery; suffered other maladies (like turf toe); and was iffy to play most of the season, missing practices but no games. Notably, the Texans won nine straight in his best pro campaign, making it hard to argue his absences hurt his team. “No evidence,” Hopkins says. “Go back and check the practice film.”

He hung with the wrong crowd. Hopkins laughs and says his best friend and housemate is his cousin, D.J. Greenlee, a marketer for a sports agency in California. He spends time with fashion and furniture designers, architects, developers, family and fellow athletes. Business leaders send him books to read. The latest: Extreme Ownership, How U.S. Navy SEALs Lead and Win. The volume is fitting, given the events of this spring, because Hopkins says it details how the best teams come together. The relevant takeaway? The necessity of organizational alignment.

His play dipped in 2019, when his yards after the catch and yards per target went down. That ignores mitigating factors. Speedy wideouts Kenny Stills and Will Fuller both missed significant time, allowing defenses to consistently double Hopkins. He still caught 104 passes, still gained 1,165 receiving yards and still had a catch percentage (69.3) that nearly matched his high, from a year earlier (70.6). Most No. 1 receivers would consider that a career year. All for a playoff T-E-A-M, he says.

What goes unmentioned is that Hopkins loved Houston, was only 20 when the Texans drafted him, that he became a leader and a mentor, immersed himself in the community, stood up for those who could not stand for themselves, found a quarterback he believed in and led Houston to the postseason four times. It’s not the city he has an issue with—and he’s not the person the fan base now targets with its ire. A Change.org petition seeking the ouster of O’Brien has more than 23,000 signatures.

Hopkins can’t help but think what he might have accomplished with Watson had they played their entire careers together, two kids from Clemson with strong ties to single mothers who had battled the worst that life could heave at them, now scrapping with Mahomes for AFC supremacy as a new NFL era dawned. Hopkins will still root for Watson. “Deshaun is going to be amazing without me,” he says.

One month after the trade, Houston moved to find a replacement atop its receiver depth chart, sending draft picks to the Rams to acquire Brandin Cooks, a speedy wideout with a long history of concussions and the rare distinction of having been traded three times; a less durable, less complete version of Hopkins. Meanwhile, Hopkins’s arrival in Arizona, along with Tom Brady’s move to Tampa Bay in the same 48-hour period, further reshapes the NFC.

As for O’Brien? The anonymous sources? Teams have different philosophies, Hopkins says, and he must respect them. “The Patriots”—where O’Brien was an assistant—“win championships without a highly paid receiver,” Hopkins says. “Some of those philosophies do work.”

Hopkins called his mother as those anonymous sources drilled holes in his reputation. “I’m not perfect,” he told her. “I’ve made mistakes. But after what we’ve been through . . .” He trailed off. She knew.

* * *

While Hopkins dealt with the aftermath of his trade, he leaned on what he has always stood for. He knew, even as an impoverished child in South Carolina, that he was different. Gifted, sure. But more than that. He didn’t dress like the other children in his neighborhood; he scoured discount stores to find colorful scarves and brand-name shirts. He argued for individuality and racial equality with anyone who disagreed. He grew dreadlocks because he discovered a widespread policy that people who wore them could still be discriminated against at work. For his individuality, he believes that he was judged long before he ever sat in O’Brien’s office.

“That’s what happens, especially in America,” Hopkins says. “That’s why I wear my hair up with pride, because I know that we, as people, drew strength from our hair. I will never cut [mine] because I know who I am. And there’s power in knowing exactly who I am.”

Hopkins always told teammates to make their own decisions, that they didn’t have to wear gold chains because other players did, but that if they wanted to, they should. When Colin Kaepernick started kneeling during the national anthem in 2016 to protest police brutality and racial inequality, Hopkins went out and grabbed 10 Kap jerseys. He caught flak from what he calls “those racist Russian bots” on social media but displayed his respect for the message publicly, with pride.

Then came the week that embodied DeAndre Hopkins, that foreshadowed how he would handle the trade this spring. Before the Texans played in Seattle that October, ESPN released a story, quoting Houston’s owner, the late Bob McNair, telling his fellow billionaires in a leaguewide meeting that “we can’t have inmates running the prison,” regarding anthem protests. Hopkins left the team’s facility the day that news surfaced, telling teammates who had said they’d join him, “S---, pack y’all stuff then.” As he walked out, Hopkins says he felt great, light, that he had done the right thing regardless of the consequences.

Hopkins denounced the comments, saying he couldn’t sugarcoat his feelings: that he felt like a slave, that this was a master ordering his workers back to the fields. But even then he showed empathy to McNair, who Hopkins noted was older and from the South, where Hopkins knew firsthand how deeply entrenched the more troubling history of America really was. Even now, without excusing McNair’s comment, Hopkins says that McNair was a good man who changed Hopkins’s life and that he hopes McNair rests in peace. Hopkins showed more understanding for McNair’s background than O’Brien would show for his. “Of course, [the inmates comment] was bulls---,” Hopkins says. “But I’m not going to feed into the negativity. America is built on certain values, and some of those values aren’t in the interest of people [like me]. That’s just the world we live in.”

Throughout his career, just as in that moment, Hopkins continued to define himself, rather than allow others to define him. He has helped his mother start a nonprofit to aid survivors of domestic violence. He dived into interior design, having planned an offseason work trip to Italy this spring before the coronavirus swept across the world. He wants to mock up more comfortable, more functional office chairs for a nation of cubicle dwellers checking on their fantasy football teams. And he says he’s closing in on starting his own business, where he will team up with the luxury brand Golden Goose, a company that he says understands that imperfection can equal uniqueness, that voice is important, that someone like him can create something more timeless than even his football career.

He’s a reader, a designer, an activist—and a football player. Did that hasten his exit from Houston? He doesn’t say that. But he does say that anyone who thinks such individuality might hinder success on the field should check out the career of LeBron James. “I don’t think anyone would dare say he’s hurting the team,” Hopkins says.

* * *

Friends have tried to make Hopkins feel better, calling the trade the worst in the history of Houston sports. He appreciates the sentiments, but in a way they’re no different to him than the barbs coming from those anonymous sources. Instead, a quote from one mentor resonated more than any other. What happened yesterday isn’t real.

“Meaning,” Hopkins says, “that no matter what happens, you have to move forward.”

Anger won’t help him in Arizona, which is why he’s not demanding a new contract, even though both sides are working toward one that might make him the highest-paid nonquarterback in the NFL. A presumably friendlier coach in Kliff Kingsbury should help. So will a cast of talented teammates, including Larry Fitzgerald, the future Hall of Fame receiver; speedy wideout Christian Kirk; versatile running back Kenyan Drake; and another dazzling young quarterback in Kyler Murray, the 2019 Offensive Rookie of the Year. The Cardinals finished tied for 16th in scoring last season, with a first-year coach and QB—before adding DeAndre Hopkins. “Obviously, the game is changing,” he says. “The Chiefs won the Super Bowl with the kind of offense we have.”

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, Hopkins won’t be able to work out with Murray this spring. Weeks passed before he could take his physical, but Hopkins passed, as did David Johnson, making the deal official. He can’t yet move to the Phoenix area because of the same precautions. But he’s not worried. He never is. The first thing he did after the trade was donate $150,000 to coronavirus relief efforts in his new state. “I’m a stress-free person,” he says. “I live in the present. I only care about this T-E-A-M.”

A shot at O’Brien, a look to the future and the same theme again bubbling to the surface. “Change is good,” Hopkins says. “It’s not weird, this time we’re living in, because if you’re spiritual, you understand that right now it is time to change.” No one could have predicted what’s happening, he says, lamenting the deaths and the restrictions. “That’s never good,” he continues. “But I see the world coming together, organizations and people working to help and protect each other. We’ve never had anything like that, either, for humanity to pull together like it is now.”

“Peace and love,” he says as he hangs up, on another afternoon when yesterday wasn’t real but tomorrow surely will be.

This story appears in the May 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Latest News and Videos from Sports Illustrated

- Albert Breer: Tua's Fate Remains the Biggest Mystery, How the Mock Draft Played Out and Other NFL Notes

- Pat Forde: Thank Goodness for the 2020 NFL Draft

- Today in Sports History: This Day in Sports History: Michael Vick Drafted First Overall

- Hot Clicks: Michael Jordan is Having Trouble Selling Expensive Home

- Daily Cover: Michael Pittman Jr. Can't Catch a Pass

- Point After: The Point After: This Year's Draft Is Shrouded in Uncertainty

- What’s On TV Tonight: April 20th Sports Guide

- Will the NFL Schedule See Changes Due to Coronavirus?