To Beat Tecmo Bowl: One Man’s Modest Quarantine Quest

I first stumbled upon Tecmo Bowl in my uncle’s basement back in the early 1990s buried amid a stack of classics like Legend of Zelda, Mike Tyson’s Punch Out!, and Konami’s Track & Field. For a few years, nearly every family party hosted there featured me in a semi-vegetative state surrounded by a pile of littered game cartridge holders.

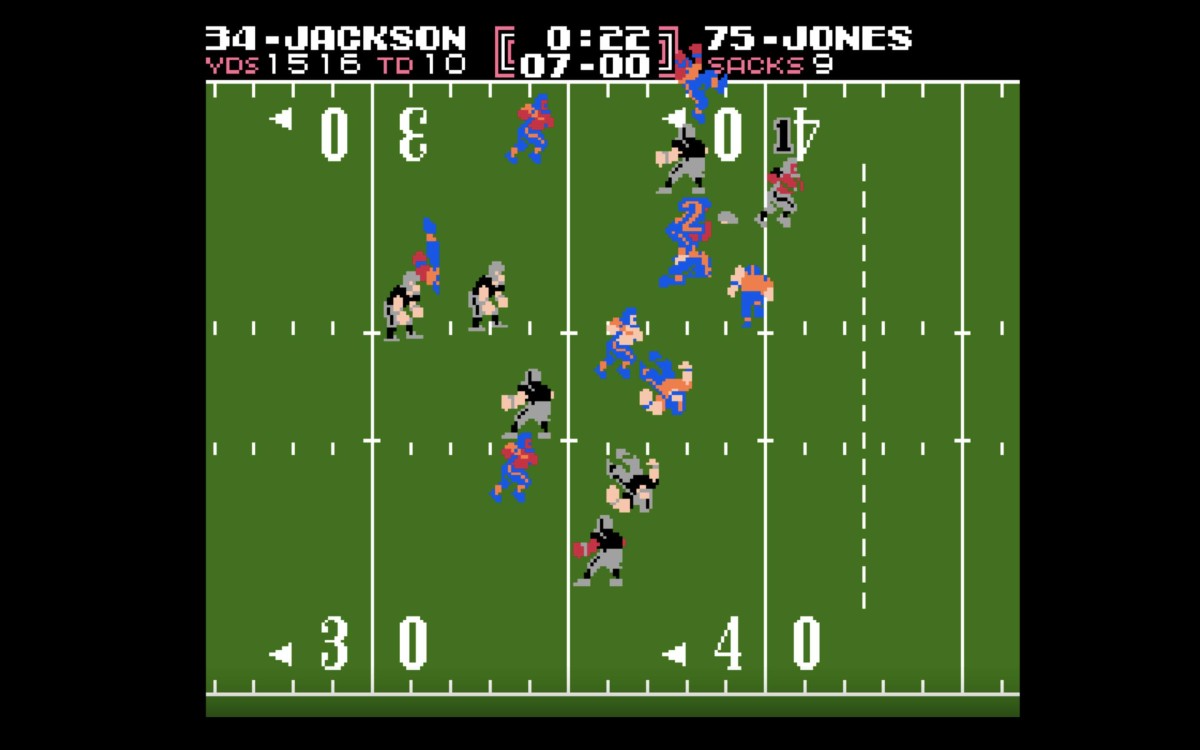

I admired the simplicity. In the original Tecmo Bowl, you can call one of four offensive plays. The defense then counters by guessing which of those four plays you called. The first iteration of the game featured classic rosters from the halcyon days of the NFL in the late 80s. It was heaven. But I never managed to reach the end of Tecmo’s season mode, which requires you beat the other 11 teams in succession.

Time passed, I got a Playstation and moved on to my great Northern Illinois dynasty in NCAA Football 2003 and, after that, the powerhouse Harvard team I imported into the SEC with every player maxed out to 99 in every category to punish college football’s elite (who says you can’t graduate players and win titles?). Though I always dreamed about getting older and having the type of disposable income that would allow for the purchase of an old Nintendo and Tecmo Bowl to finish the job.

More than 20 years later, here we are. Stuck inside with no place to go. A need to escape the toppling plutocracy and endless waterfall of horrifying news. Tecmo Bowl free to be streamed on the internet (in lieu of disposable income) via some unsecure site hosted in the Czech Republic. This is a time to finish unfinished business.

* * *

Join Conor Orr and Gary Gramling as they experience the dizzying highs and terrifying lows of a Tecmo Bowl season, podcast-style:

* * *

Before my journey to Tecmo Bowl enlightenment began, I called Brad Bell. Bell knows everything about Tecmo Bowl.

The 43-year-old Waterlogic service technician first played Tecmo after it was released in early 1989 and became obsessed with its machinations after another kid in the neighborhood beat him. Now, no one beats Bell. He has only lost once in competitive play. Ever. He has won more than 10 tournaments. The only people who can hang with him are his best friends, who have been equally obsessed with the game and have learned Bell’s tendencies; the group plays online together like a cluster of chess grandmasters.

“I feel like I’ve almost maxed out,” Bell said. “I don’t think I can get much better at the game.”

Bell estimates that he’s spent about a month of his life (more than 700 hours) perfecting the art of Tecmo Bowl. His breakdowns and observations have formed the foundation of what competitive players know about the game that launched three decades of obsession over virtual football. For someone like me, looking to satisfy a bucket list item during pandemic isolation of beating the game and winning its equivalent of a Super Bowl, this was valuable intel. Over the course of a 30-minute phone call, Bell would drop insane pellets of wisdom. If you’re the Giants playing the 49ers, call the Pass 1 defense, so Lawrence Taylor matches up on Jerry Rice and neutralizes him. If you’re the 49ers, don’t control Ronnie Lott as it will mess up the computer’s coverage algorithm and leave you exposed. If your opponent is running to the bottom of the screen, the defenders at the top of the screen will be left unblocked.

I asked Bell for some last minute advice. Was this even possible?

“Just run the ball a lot,” he said. “Run with your quarterback and minimize mistakes. Also, it’s O.K. to punt.”

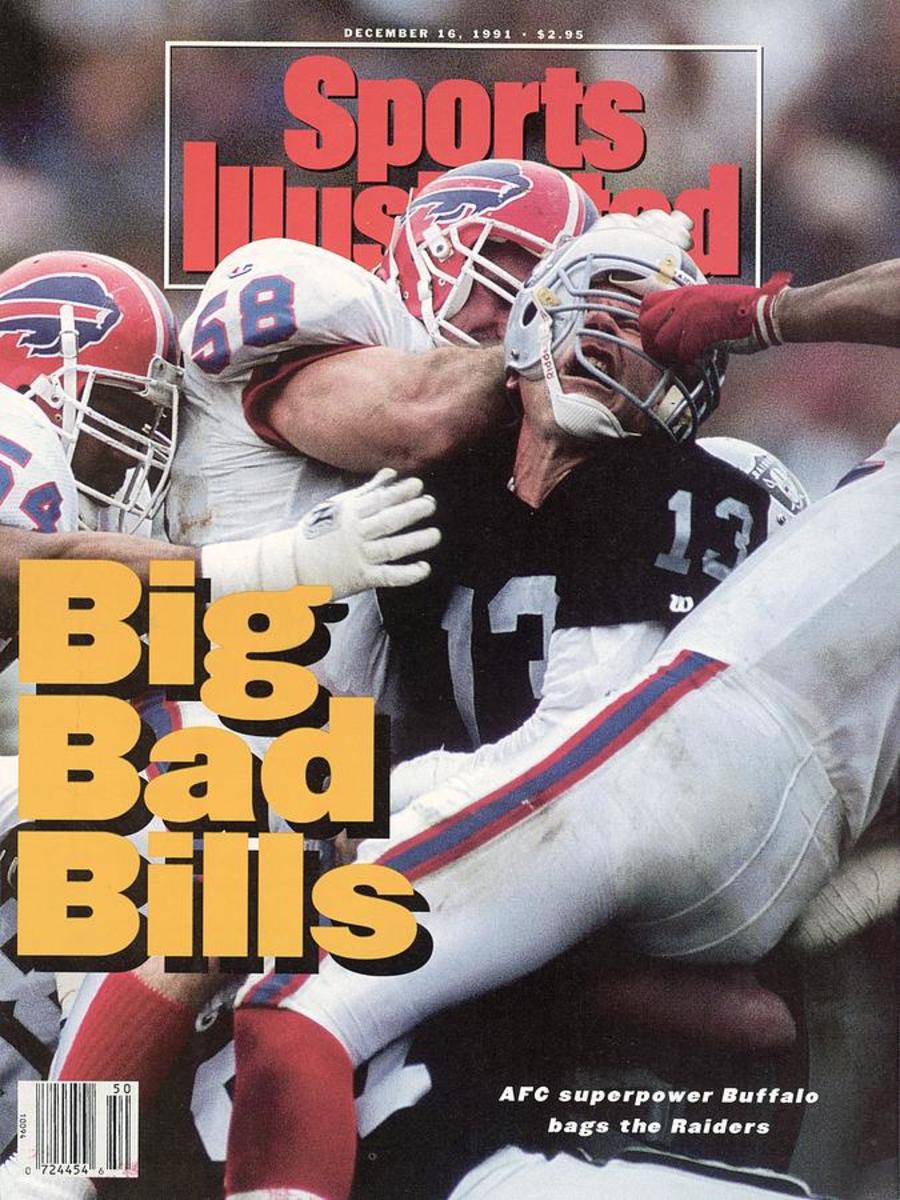

A randomized selection process assigned me the Los Angeles Raiders. Bo Jackson. Marcus Allen. Tim Brown. This is the story of our season.

* * *

WEEKS 1-4

Jack Trudeau.

Of all the possible supervillains this game could have hurled in my path—Lawrence Taylor, Jerry Rice, Walter Payton—I am being foiled in Week 3 by a journeyman with a 19-30 career record and a completion percentage dangerously close to the 50 percent line. I imagine what it must have been like to be a child of the early 1980s with only a tangential knowledge of football leaving their experience with this game believing that Trudeau was bound for Canton.

But before Trudeau took over, my first two games—despite a complete lack of strategy and technical finesse—ended in victory. Howie Long ran the length of the field to tackle Mark Bavaro at the 5-yard line, preventing the Giants from a time-expiring, game-winning touchdown in Week 1. It was redemption for the then-future Hall of Famer, who was humiliated earlier in the game when, with a grasp on Phil Simms, was not only unable to finish the sack but was keg-tossed to the sideline, spiraling off the field like a warmed popcorn kernel. Week 2 brought the Vikings, a team notoriously handicapped due to the fact that their playbook features a doomed-on-arrival reverse as one of their four options. The game proved to be devastating to my inner play-calling calibration, as I ran “Pass 2” with success over and over again, with no defender bothering to cover Tim Brown on a deep vertical at the bottom of the screen.

Here I was, marinating in undeserved confidence. Sure, Jay Schroeder takes longer to wind up than Hideo Nomo, but that doesn’t mean I can’t make it rain. I was ignoring my best offensive weapons (Bo Jackson, Todd Christensen, Marcus Allen) like a late-80s version of Pat Shurmur, without recourse. And then came Trudeau and the Colts.

I understand how people take video game losses personally. Once, during one of those formidable high school parties without parents and a seemingly unlimited supply of alcohol secured through questionable means, a good friend and I remained in the basement gridlocked in a series of heated Rushing Attack minigames on Madden 2004, unable to agree on who could better pilot Clinton Portis around a series of movable blocking dummies and defenders. Dozens of people filtered in and out around us, swilling Keystone Light and enjoying their first glimpse at that elemental, youthful freedom. We screamed at each other over the game’s cruelly inconsistent deployment of the “truck stick” and went home sober.

Somehow, at 31, these losses felt more sinister. In Tecmo Bowl, you don’t just lose to an opponent and move on to the next week. You remain in the stadium. You have to play that opponent over and over again until you can win and move on; it’s less like progressing through a season schedule and more like taking on a level boss in a role-playing game. Imagine if that happened in real life. The 2007 Jets would still be trying to get out of Foxboro.

Trudeau kept buzzing passes to Matt Bouza and Pat Beach. When I retreated into pass coverage, Eric Dickerson would break a long run. When I pinged Howie Long and hurled him into the backfield, Trudeau would light me up over the top. Matchup one ended in a 48-28 loss. Matchup two, 34-28.

And playing on a (questionable) streaming site hosted in eastern Europe—that frequently ran ads for a highly sexualized for-pay online wizard game—there was no reset button when the score got out of hand. I had to take the punishment.

* * *

WEEKS 5-8

I’ve learned that, in this game, true strength comes from the heroes you did not expect to find. My hero’s name is Bill Pickel.

A quick thumbing through Wikipedia taught me that the real William George Pickel was a Queens-born defensive tackle who would go on to play at Rutgers and enjoy an 11-year career in the NFL. He was a great NFL player, just one who existed before my time. There was a three-year stretch between 1984 and 1986 where he had 36.5 sacks and earned a first-team All-Pro nod. After retirement, he also guest-starred on an episode of Home Improvement, in which Tim and Al assemble celebrity-laden teams to aid them in a Habitat for Humanity home-building challenge (Tim doesn’t want his wife, Jill, on his team because he’s a classic chauvinist but learns the error of his ways when Jill assists Al’s team in claiming a victory).

The fun of playing a season mode: You can create your own narratives and make your own stars. In college, my freshman roommate and I played a Madden season in which he became obsessed with the idea of having former Rams and Bills tight end Joe Klopfenstein finish the season as the leading vote getter for the Pro Bowl. There were nights when I would watch him pummel opponents by running the same goal line formation bootleg pass to Klopfenstein over and over. By the mid-season point, when the league fizzled out, he already had more than 30 touchdowns (in real life, Klopfenstein had 58 career catches and two touchdowns).

In my Tecmo Bowl universe, Pickel was a combination of Reggie White, Joe Greene and Dick Butkus. He became integral to my new defensive strategy, which was to always select a running play since they’re so much harder to stop, then drop either of my linebackers (Matt Millen and Jerry Robinson) into coverage and follow one of the wide receivers in hopes of picking off a pass. Against teams that regularly featured the run (Bears, Cowboys, Browns) the AI-controlled Pickel was a fixture in the backfield, burying Payton, Kevin Mack and Herschel Walker. There’s a good chance he would have broken Pro Football Focus’ grading metrics with an estimated 400 tackles for loss.

Throughout the process, I wondered how frustrating this would be to read for legions of 40-somethings who had honed this strategy over long hours wrapping sore, calloused hands around the hard plastic rectangle controller. The real grinders who knew and loved Pickel long before I did. My hope is that they view this as an homage, and not another dangerously offensive action from a millennial out to destroy everything they love.

Once Trudeau was in my rear-view mirror, I dispensed of Chicago 24-20, Dallas 35-13 and Cleveland 41-21. My only stumble came in a stunning 34-14 loss to Washington before correcting course on a second attempt. It was during that game, in which I was intercepted four times by Dexter Manley, that I began to wonder if the artificial intelligence built into this 8-bit system had any actual machine-learning capabilities. Was I still this bad, or was Manley a sign of a gradual rise in difficulty? How did he seem to know that, on Pass One, I liked to roll up screen and wait for Marcus Allen to pass the nearest defender before hitting him for an easy first down?

Six hours in, more questions than answers.

* * *

WORLD FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP

I remember getting misty-eyed at the finale of Sonic Adventure 2 for Sega Dreamcast when Shadow, having vanquished the dark side, sacrifices himself in order to save humanity. Soft piano music plays as he freefalls from space back to planet earth. No finale in music, literature, game or film has come close to producing the same emotional response from me.

Before I could find out what lies ahead in Tecmo, a gauntlet of the game’s best arms awaited me: John Elway, Dan Marino and Joe Montana. And Dave Krieg.

After defeating Denver, Miami (also featuring Dolphins defensive end John Bosa, father of Nick and Joey, intercepting anything in a three-mile radius) and San Francisco, Seattle, with its confounding neon pink uniforms, was thought to be an anticlimactic championship opponent. The game kicked off as afternoon blended into evening. An editor texted to check on my progress late in the afternoon. “I can’t beat the f---ing Seahawks. Need to break for dinner. Call you in an hour.”

But the initial setback, a 42-21 loss, was merely a prelude to ending the quest in a near-perfect way. In game two, Bo Jackson scored four times. Tim Brown caught a pass over the middle for a touchdown. Marcus Allen, irrelevant for large stretches of the season, got to run in a touchdown on a slow-developing run play to the bottom of the screen that was (finally) left undefended.

And, with the game on the verge of a complete blowout, I selected Bill Pickel and let him drop back into coverage the way I imagine a fun coach would let a beefy offensive linemen carry the football or throw a pass with the season nearing a satisfying end. He was every bit as graceful as I hoped, and picked off a pass.

When you beat Tecmo Bowl they show a generic coach who looks a bit like muscular Roy Orbison on the shoulders of his team being carried off the field. You then get to see the trophy—the World Football Championship—which has the shape of a faceless cobra and is covered in gold. The roster scrolls by and the credits roll. For a moment, you think about where Akihiko, the programmer, is doing now. Or K.Y. Jet, who composed the music. You think about Bill Pickel returning to the Bronx, perhaps to some deli where they will change the name of the Dill Pickle to the Bill Pickel forever in his honor.

And then, after the legal copyright information is displayed, the final thing you see is a single word in all caps that ascends to the middle of the screen, remaining for a few beats:

“END”

It’s something I’m glad I got to see. Simple and definitive. Something I doubt the 10-year-old me would have appreciated back then.