Austin Ekeler’s Underdog Story Is Complete . . . Almost

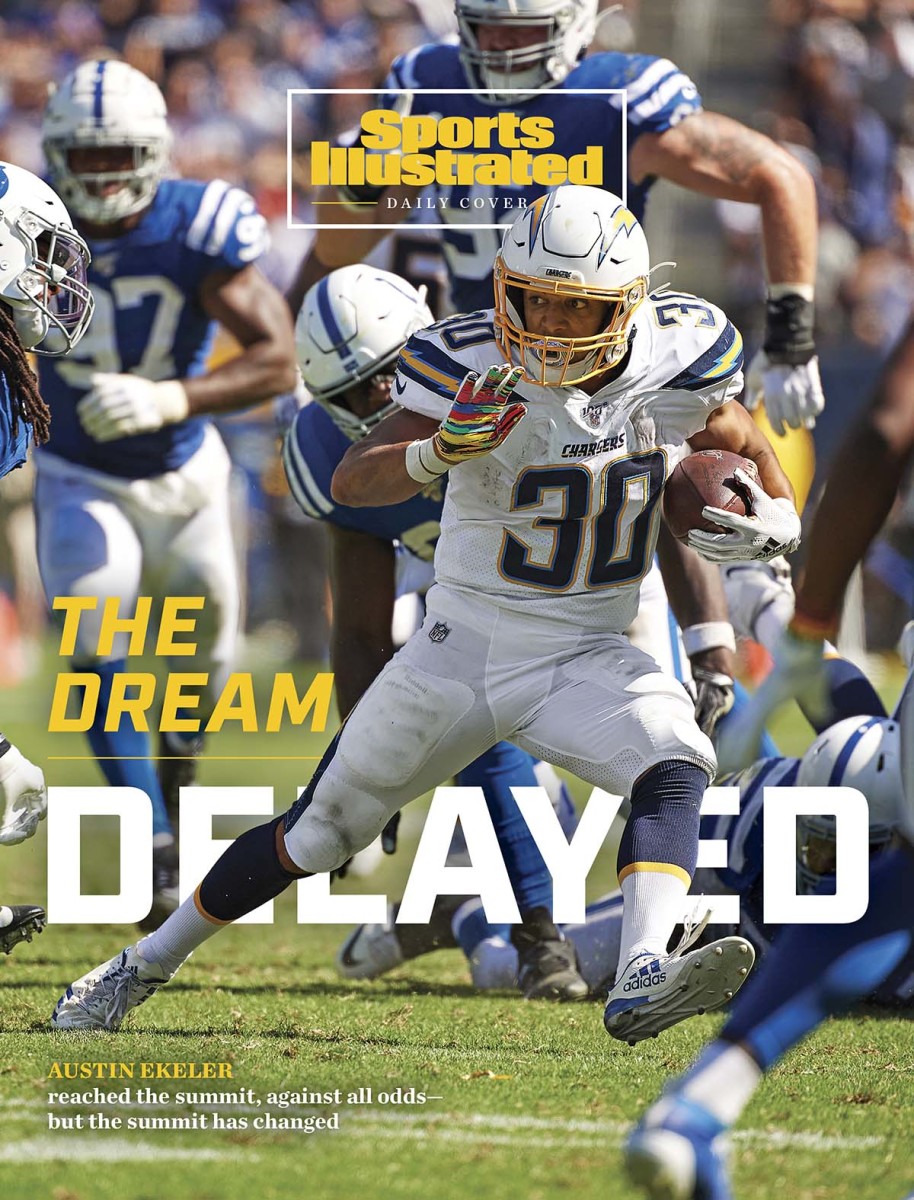

Austin Ekeler sat down at a conference table, before the new house and the swollen bank account, before the online workouts and the videoconference playbook sessions, before he swapped his supporting role for a feature one and his No. 30 Chargers jersey for an N95 mask. It was early 2020, before his world changed, and before the world changed. He was meeting with general manager Tom Telesco, pondering the same notion that has dominated the best and strangest year of his life.

How did I end up here?

“We really want you,” Telesco told him. The GM saw Ekeler as a key piece to the franchise’s rapid rebuild after a 5–11 season, adding another layer of resonance to one of the most improbable stories in recent NFL history. The one about the undersized running back, overlooked by every Division I college program, then ignored even by nearby D-II schools, who wasn’t invited to the combine; who crashed another school’s pro day; who went undrafted when 27 backs—27!—heard their names called. And the one about the kid who never knew his biological father and wished he had never met his stepdad.

That man in that meeting had never planned on playing in the NFL. He only hoped—he knew the odds. Even when Ekeler made the Chargers as a special teamer in 2017, he wondered just how long he might stick; in fact, he went back to college after that first season. He knew he needed to finish his degree in energy management, because he needed something to fall back on. He figured he might latch on with Noble Energy, the hydrocarbon exploration company that he had interned with.

Instead, he carved out a part-time role on offense in his second season and cemented his value last year when starting back Melvin Gordon held out. Ekeler’s breakout in ’19 unfolded like the build toward the climax in an underdog sports movie, featuring a scrappy protagonist faced with insurmountable odds, in search of the right break, bolstered by his support system and then … 1,550 yards from scrimmage, ninth-most in the NFL and fourth-most in the AFC; 92 receptions; almost 1,000 receiving yards; 11 touchdowns. The real-life script landed him in that office, across from his general manager, who would sign Ekeler, now 25, to a four-year deal worth $24.5 million, with $15 million guaranteed. The big scene, naturally, was somewhere on the near horizon.

Ekeler drove to Las Vegas for a celebratory steak dinner with his agent, Cameron Weiss. He called his mom, Suzanne, who screamed in celebration. He heard his girlfriend, Taylor Frick, say his life “felt like a fairy tale.”

Then came COVID-19, the respiratory virus that halted momentum and plans and dreams—like those held by the running back who had lived out three quarters of a movie, who had finally arrived, against every reasonable expectation, to the best part. The gym he worked out at closed. So did the public spaces at his apartment complex. So did the Chargers’ facility. Full stop, all around. Ekeler wondered how he might capitalize on his moment and finish the fairy tale, while confronting an unforeseen villain: a global pandemic.

* * *

The magical tale of the diminutive hero begins in Eaton, Colo., a small town of roughly 4,500 people located some 70 miles northeast of Denver, near Greeley. Ekeler grew up a short drive from the city limits, moving there soon after his biological father went to prison, a topic that he prefers not to discuss. When his mother remarried, and they moved into her new husband’s 80-acre ranch.

The idyllic setting served as a stark contrast to the Ekelers’ new, harsh life. The boys became full-time employees, more or less, a pair of young ranch-hands. They tended to horses, cows, chickens and goats. He and his half-brother, Wyett, would be awoken at 6 a.m. for backbreaking chores, even in the winter, when they were sent out to break apart ice in water tanks. In the summers, they helped install and fix the fences around the property, the posts stretching for mile after mile. Asked if he loved one animal more than any other, he says, “I hated all of them because I hated taking care of them.” He pauses. “Well, there was a goat,” he says. “She just kind of ran around when we did the feedings. We named her Betsy.” (In the Disney version of the movie, she would become his animal sidekick.)

During those years, Ekeler learned what he needed to survive. His drive, for one. His mindset, for another. And his mom, a math teacher who played basketball in college and took on extra jobs like as a waitress each summer to help the family. She shielded Austin, pointing him to another way, ferrying him to practices and games in soccer and track and football. On one car ride when he was nine, she told her Austin he would be special, do great things. He looked back at her and laughed with a mild annoyance, giving her one of those mom?!?! looks.

Over time, he started to believe, in both himself and what might be possible, even when others missed what fueled him. He desperately wanted to win, at anything; more urgently, he wanted to escape. He didn’t even love football, not the way that his obsessed teammates said they loved it. Rather, he saw the sport as his best chance to both succeed and leave, the ideals intertwined—two birds, one sport. But even when he scored 42 touchdowns and amassed almost 2,400 rushing yards in his senior season, Division I schools passed without so much as responding. Division IIs that did get back to him asked him to switch positions. Every program, that is, but one he’d never heard of: Western State Colorado University.

Ekeler left for college on the same day he received his high school diploma, having secured a summer gig as a rafting guide on the Taylor River. He drove his overstuffed pickup to Gunnison without so much as a glance over his shoulder, speeding toward his new life in the small college town nestled high in the mountains with a football team years removed from its heyday and eight other running backs crowded onto the depth chart.

Still, he started the first game of his freshman season, a nod to the impression he’d made that summer. Teammates most often found him in the weight room, squatting more than offensive linemen, 10 massive plates bending the barbell that rested atop his shoulders. Ekeler befriended a defensive lineman named Jared Martin, and they spent their limited free time out on the river, casting for fish. The running back always caught more. He had to, so he could good-naturedly taunt Martin on the drive back to campus. “That was Austin,” Martin says. “Pretty much unstoppable from the day he arrived. Scored every touchdown. Hooked the most fish.” (The Herculean character had begun to take shape.)

Ekeler starred but not in the same way as most college football heroes. He never played on national television or caught a pass from a five-star quarterback. He performed at home games in the Mountaineer Bowl, with its sweeping scenic views and modest metal bleachers, usually in front of a few hundred fans. “It kind of fit me,” he says, meaning he didn’t need any extra motivation. In four seasons, Ekeler broke every conceivable rushing record at Western, finishing with nearly 6,000 rushing yards and scoring 63 times. In 2016, the program managed seven wins for the first time in almost two decades, behind the captain who performed air guitar solos after touchdowns. “He was so dominant, but still, you wonder, because it’s D-II,” his mother says. “We didn’t know if there would be a next step. We didn’t even know how to go about the process.”

As Ekeler’s senior season unfolded, NFL scouts began to drop by practice, which seemed to indicate a genuine interest in the small back (5' 10", roughly 200 pounds by then) from the small school. The Packers seemed mildly intrigued, as did one particular personnel member of the Chargers, Tom McConnaughey, who told Ekeler he should at least be able to earn a minicamp tryout.

Eventually, Ekeler found out he could test for teams but only after the University of Colorado held its pro day, even though some scouts would already have left. That was all the chance he needed. The personnel folks that lingered, half-focused, looked up from their notebooks when he clocked a 4.43 40-yard dash and logged a 40.5-inch vertical leap. At that year’s NFL draft combine, only future first-rounder Christian McCaffrey had posted comparable specs. Ekeler’s mom watched that pro day from the field. Suzanne was struck less by her son’s accomplishments and more by the fact that the wider world had started to take notice, and it would continue to, all the way up to the moment he signed that contract.

* * *

What Has It Been Like Navigating an NFL Offseason During a Global Pandemic?

* * *

Before the lockdowns started, Ekeler enjoyed a blissful existence. He lived near the beach, where he’d meet teammates for games of Spikeball. He could buy anything he wanted. He was healthy, happy. His brother landed a football scholarship at Wyoming. His mom had moved to California. He had started to look for a house of his own, with his girlfriend, another step toward building their own family. He joked sometimes about the mad dash of crowds rushing to scoop up toilet paper, or the boxes of hand sanitizer flying off the shelves. But his tenor didn’t change until sports shut down and he became a model of social distancing. He left his house only to go to the park nearby for workouts or pick up food, reasoning that he could deploy his growing platform by setting an example for his more vulnerable neighbors.

To keep alive the tale, Ekeler started to get creative with his workouts, especially after he saw Steelers back James Conner throwing logs in the woods. Ekeler did push-ups with Frick sitting on his back. He knocked out one-arm pull-ups while reading a book.

Ekeler had no contact at that point with his teammates, while the Chargers began their roster overhaul. Telesco traded offensive tackle Russell Okung to Carolina. Gordon signed with Denver, clearing the path for Ekeler to become the team’s primary back. And the team declined a chance to re-sign quarterback Philip Rivers, marking three offensive starters, three leaders, gone in roughly three weeks, along with the NBA and NHL seasons. Ekeler wondered whether the Chargers might sign Tom Brady, until he went to Tampa instead. But he didn’t even hash out the rumors with his teammates. They had all retreated into their own bubbles. “We’ve been so distant,” he says. “There’s definitely a disconnect throughout the entire NFL right now.” (In the movie, this would mark the surprise setback before the championship.)

As the self-isolation dragged on, Ekeler started to channel his boredom into productivity, making the most of his time like he had at Western, formulating plans. He streamed full-body aerobic workouts with his girlfriend over Twitch and formed a video game streaming business that would allow pro football players to connect with fans while they play League of Legends, FIFA or Madden. He called the company Gridiron Gaming Group, registering it as an LLC with his agent and a friend. Ekeler was always that resourceful. He had to be; he had considered starting a fishing business with Martin before the football thing worked out. “I’m actually not bored at all,” he says. “But I miss football.”

News remained his only connection to the game. He cheered when he saw the Panthers ink McCaffrey to the largest running back contract in NFL history, with $30 million guaranteed, one season after McCaffrey logged 403 touches. “I don’t honestly think my body could handle that much volume,” Ekeler says of McCaffrey’s workload.

As the draft approached, Ekeler hoped the Chargers would select a running back, since only he and Justin Jackson remained on the roster at that position. He still hadn’t had any contact with his teammates, his new starting quarterback or his new offensive coordinator. His days were filled, but not by the activity he most wanted. He liked the new collective bargaining agreement, because it raised the pay of younger and less established players, guys like him before this spring. He worried about the extra game that would be added to the regular season, especially for running backs who would endure another afternoon of car-crash-like collisions. And he wondered about the small-school stars who were preparing for the draft the way that he had three years earlier, and what might have happened had the Chargers’ scout not visited his campus, or had he not been able to sneak into that pro day. Would he be working in energy management instead?

* * *

What Are the Players' Perspectives on the NFL's New CBA?

* * *

Ekeler began to inch back toward his fairy tale in May, at least virtually. Everything was different. He met online with Jackson and his position coach four mornings a week, from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. The entire offense also hopped on larger videoconferences with Shane Steichen, an assistant who turned last fall’s interim coordinator gig into a full-time post.

Like most teams coming off a losing campaign, the Chargers continued a significant overhaul. L.A. needed new leaders. Steichen installed a new system, with different terminology and more emphasis on quarterback mobility, after the team took Justin Herbert from Oregon with the sixth pick, meaning the Chargers would transition from their statuesque legend in Rivers to a more mobile option (Herbert or veteran Tyrod Taylor). Herbert immediately sent Ekeler a text message, hoping they could coordinate to fine-tune some routes before training camp begins, whenever that may be.

They had also bolstered the running backs room, per Ekeler’s wish, taking UCLA’s Joshua Kelley in the fourth round. As a bigger downhill runner, Kelley would seem to complement the Chargers’ current backs well, and his selection, along with a handful of the spring’s undrafted free agents, helped fill out the sparsely populated videoconference room. Ekeler had already called Kelley to help him familiarize with both the organization and the offense, trying to alleviate his biggest coronavirus-related concern: that teams with new systems or new quarterbacks will enter the 2020 season at a disadvantage, because of the lack of time that any group can spend together. The Chargers are new in both places, new everywhere, and while Ekeler is optimistic about their revamped roster—“We can compete for the division”—he’s also aware that many pundits disagree, ranking his team in the bottom half of many projections for next season. “Story of my life,” he says.

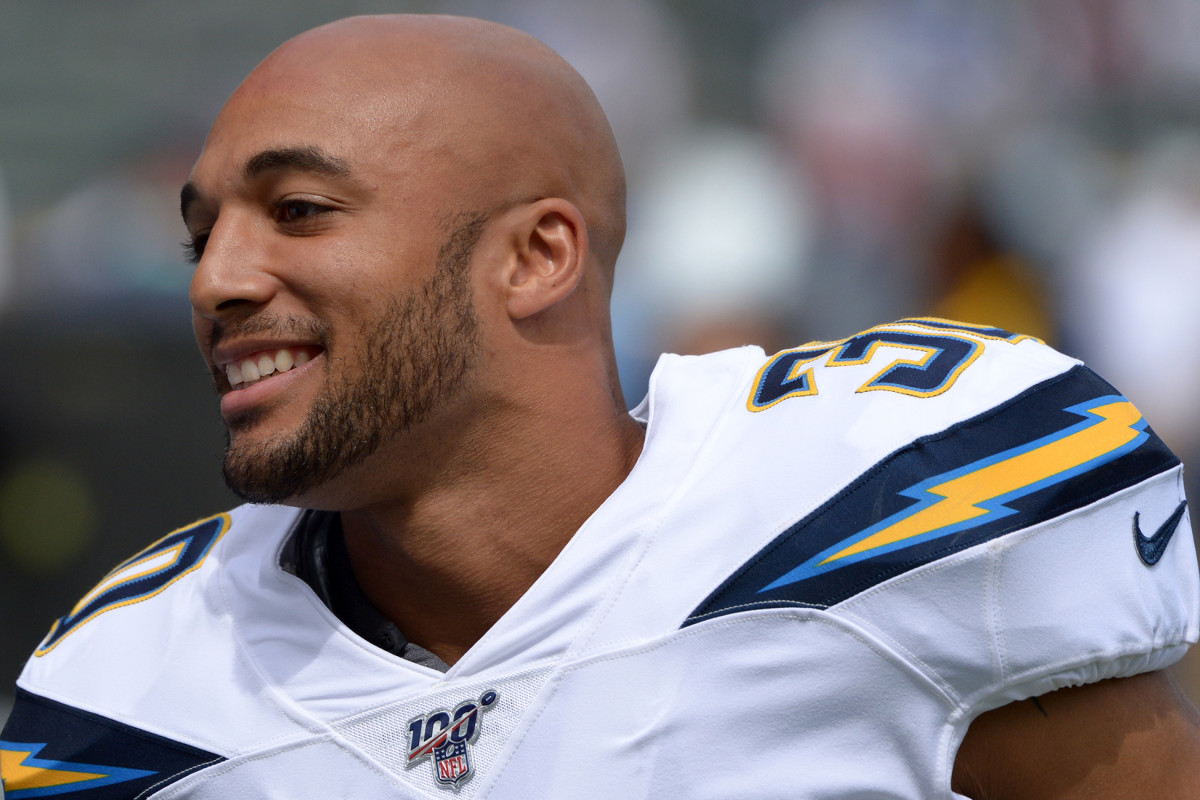

Yes, he signed the contract, became a multimillionaire and started two new businesses. But he still ate his celebratory dinners at Red Robin, still saved most of every NFL check, still approached each day like a ranch hand or the ninth running back at a Division II college.

Ekeler remains the same competitor who threw up before his first pro practice because he so desperately wanted to succeed. The same back who cornered coach Anthony Lynn after rookie minicamp and then—after Lynn asked Ekeler, Who are you?—followed his advice to make the roster through pass protection, ball security and special teams. Who taped up a broken left hand his rookie season and never missed a game. Who was waylaid on a return against the Bengals in Year 2, losing feeling down the left side of his body, yet missed only two weeks.

He continued to place his story and the pandemic in the proper context: He had it great compared with all the people who were sick, or worked in hospitals, or lost their loved ones. His dream had simply been delayed, and the new complications only made for a better story.

That’s the thing about Austin Ekeler this spring. His world changed. Then the world changed. The man himself? Everything changed and nothing did. Now, about that ending …