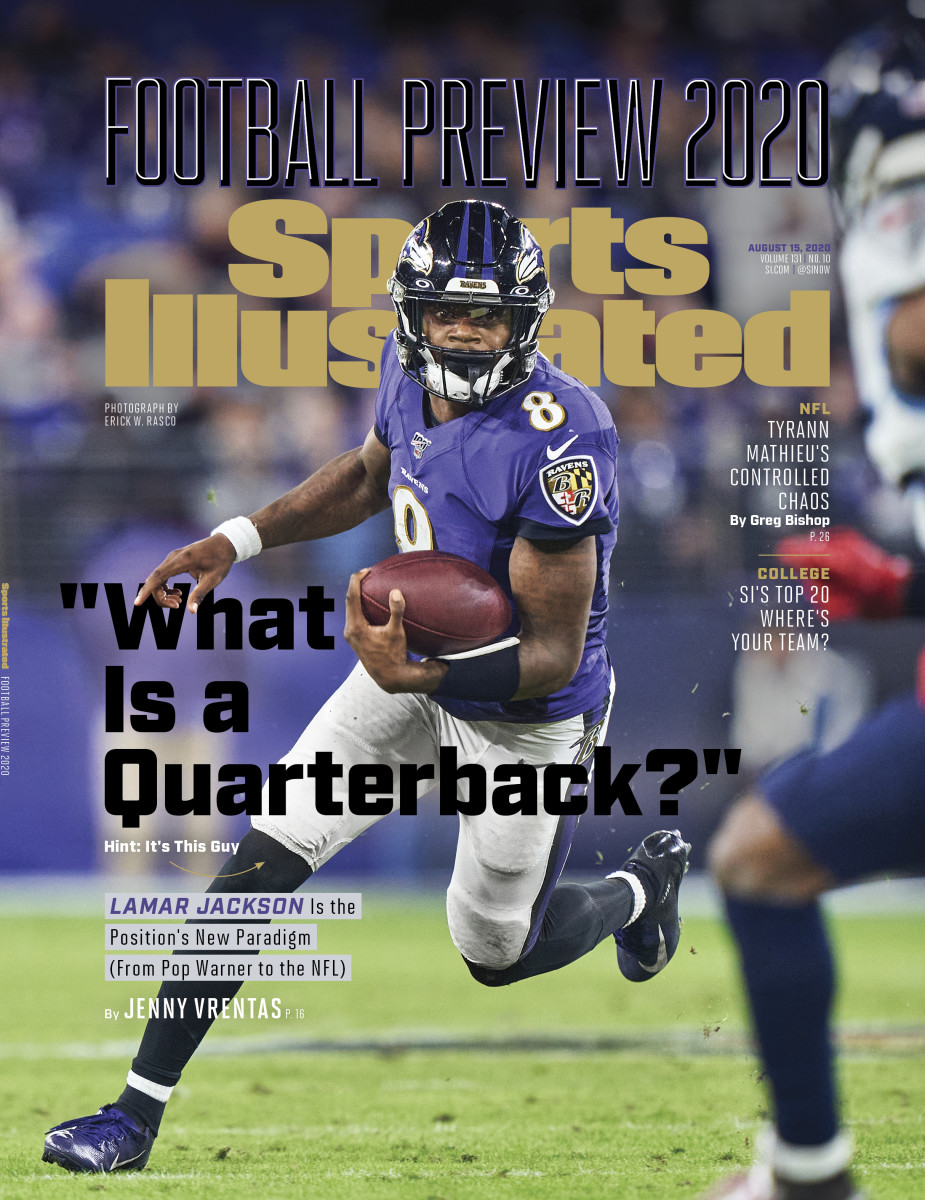

Lamar Jackson: Quarterback, Redefined

“What is a quarterback?” This question was asked on the second Wednesday in January in the Ravens’ locker room, a few stalls down from a Christmas tree that was still standing, evidently in the name of superstition as no one wanted to jinx the team’s 12-game winning streak. All around the building, and all through the city of Baltimore, was a new world of Lamar Jackson’s creation.

Later that week coach John Harbaugh had shown up at a press conference wearing a hoodie from Jackson’s Era 8 apparel line, emblazoned—like many of their items—with an African wild dog. A donut chain sold pastries printed with the “Big Truss” team motto based on a Jackson catchphrase, loosely defined as mutual trust (and since changed to “Big Truzz,” to avoid a trademark dispute). And on the eve of the No. 1 seed’s opening playoff game, Jackson and two teammates surprised the neighborhood of West Baltimore when they arrived at Miss Carter’s Kitchen, picking up a to-go order of seafood pasta, mac-and-cheese, collard greens and the restaurant’s famous banana pudding.

Then, that Saturday night, the Ravens’ season ended. Jackson stood at a podium after a 28-12 loss to the Titans, sweat on his brow, still wearing his uniform pants, everything about the conclusion of his MVP season feeling abrupt. Hours later, the skies opened up, rain cascading over Baltimore.

Much has changed in the seven months since: Patrick Mahomes and the second-seeded Chiefs represented the conference in the Super Bowl, and won. Then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, disrupting offseason plans and enveloping the NFL with concerns about fulfilling its schedule. But whenever games resume, the expectations for Jackson pick up right from where they left off in January.

And the 23-year-old will continue to provide new answers to the question thoughtfully posed then by veteran cornerback Brandon Carr—“What is a quarterback?”—that will be central to the league and to all levels of football, now and for years to come. What Carr and the rest of the country saw last season was the emergence of a quarterback who truly integrated his rare ability as a runner with his rapidly improving skills as a passer; who didn’t feel the need to define himself by one or the other; whose guiding principle was simply to get another first down. It was refreshing—not if you were an opposing defender, but certainly if you were sharing a locker room with Jackson, as Carr, now a free agent after 12 NFL seasons, did for two years.

“In 2020, this is how quarterbacks are going to play,” Carr said. “And I am pretty sure if you look at the little leagues right now, those coaches have been having their best player doing those things. We can redefine quarterback right now.”

* * *

One year earlier, after the first playoff loss of his NFL career, Jackson had vowed to begin and end the 2019 season in Miami, site of Super Bowl LIV. The September opener against the Dolphins went as he planned but as no one else could have imagined: Jackson threw five touchdown passes with no interceptions and had a perfect passer rating in a 59–10 win. As he walked off the field in Hard Rock Stadium, he reached into the stands to give the white towel that had been tucked in his waistband to a teenage QB named Hezekiah Harris, the son of Jackson’s throwing coach, Joshua Harris.

Jackson did end the season in Miami, too, but only to accept the MVP award. So he looked at Harris askance a few months after the loss to Tennessee, when his coach said to him, “You’re the MVP now.”

Since they began working together before the 2018 draft, Harris has learned that the best way to motivate Jackson is to tell him something he did was garbage. For the fifth QB chosen in 2018, and a three-star recruit entering college, slights are motivating. So the MVP remark wasn’t flattery from Harris—he was warning that the target on 6' 2", 212-pound Jackson’s back would be even bigger in 2020. The rest of the league would be homing in on solutions to slow the only QB in history both to pass for 3,000 yards and rush for 1,000.

“They’re preparing for me,” Jackson replied, “but I’m preparing even more for them.” (Jackson declined an interview request.)

Jackson’s second season was a quantum leap from his first. That kind of jump is not unheard of for quarterbacks, though how it happened was. The Ravens changed offensive coordinators, promoting Greg Roman from tight ends coach; they went all in on a scheme that dared to feature its quarterback as the centerpiece of its passing and rushing attacks; and Jackson did what NFL evaluators have long considered rare—he became significantly more accurate as a passer. Last offseason Harris ran drills he learned while attending a clinic with Tom House, throwing coach to greats such as Tom Brady and Drew Brees, to make sure Jackson’s footwork was sure in the pocket, no matter how chaotic it got. Jackson’s completion percentage soared from 58.2 as a rookie to 66.1 despite a more complicated passing scheme that featured more difficult throws.

But the way the season ended has been “the only thing on his mind,” Harris says. Jackson told Complex’s “Load Management” podcast earlier this year that the Ravens got caught “peeking ahead” as heavy favorites against the Titans. It wasn’t that the game plan that dominated opponents all season failed; instead, the Ravens ditched it once they fell behind 14–0, passing almost three times as often as they ran. Harris thought his pupil was, subconsciously, trying too hard to be the MVP in his desire to salvage the game, and the season, for his teammates and the city. Jackson moved the offense—Baltimore’s 530 yards were the most in a playoff game over the past two postseasons—but two failed fourth-and-1 conversions (after going 8-for-8 during a 14-win regular season) and three turnovers kept the Ravens from putting up points.

Even before this year’s offseason program went virtual, Jackson was engrossing himself in film study. His Ravens coaches have praised his uncanny field vision, but he set out to amplify that by dissecting coverage disguises and quizzing himself on where he should go with the ball when he sees certain shifts and blitzes. “As he calls it, getting his Tom Brady on,” Harris says. In early June, Jackson gathered teammates in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.—before the NFLPA had advised against such practices—for a few days of group work, refining his deep balls and throws outside the numbers. Harris noticed that Jackson had a tendency last year to spring up on his toes, causing him to pass with too much arm and lose velocity—an issue that especially showed up on those outside-the-numbers throws. They worked on keeping his cleats on the ground, forcing him to use his lower body and generate the necessary power on those more difficult deliveries.

“The stigma of being ‘dual threat’—and I say that with the air quotations—used to mean being a runner but now it really means dual threat, doing both,” Harris says. “But I’ll be the first to say this: It’ll take consistency. If he comes back next year, he does similar or better, then people will start to realize, this is the way the position can be played.”

But there has already been a shift since Harris designed Jackson’s Pro Day workout at Louisville with all 59 of his throws under center, and some with multiple receivers crossing the field to simulate his going through a progression, addressing skeptics of his passing-game mastery head on. One of the 50 votes Jackson received as the unanimous MVP came from Bill Polian, the Hall of Fame general manager who suggested on ESPN’s platforms before the draft that the 2016 Heisman Trophy winner should play as a receiver in the NFL (Polian voted Russell Wilson as the first-team All-Pro QB, his way of splitting his ballot between two deserving candidates). Polian had praised Jackson’s dynamic abilities with the ball in his hands but questioned whether he had the durable frame or passing accuracy to project as an NFL quarterback.

“I was wrong. Simple as that,” Polian says now. “I didn’t see what [then-Baltimore GM] Ozzie [Newsome] and John [Harbaugh] saw. They got past the idea that you can’t have a running quarterback—a guy whose game is a combination of throwing and running. They recognized that you could do that if the guy had enough shiftiness, enough ability to make tacklers miss, that he wasn’t exposing himself to a lot of big hits.” Polian adds, “The paradigm has changed, no question about it.”

Newsome, then preparing for his final draft, was adamant at the 2018 combine that on their draft board—one of the most respected in the league—Jackson was a QB. And after Jackson’s Pro Day workout, James Urban, Baltimore’s quarterbacks coach, found Harris and told him he loved what he saw. He had been on the Eagles staff when they had Michael Vick, and Harris recalls Urban asking questions about Jackson’s learning style.

The Ravens, of course, still passed on Jackson. They moved down from No. 16 to 22, then again to 25, where they selected a tight end that they’ve since dealt (Hayden Hurst). They traded back into the first round to take the future MVP at No. 32. In every draft room, including Baltimore’s, grades on Jackson varied because his skills challenged traditional scouting checklists. But his supporters were adamant: In one Ravens predraft meeting, an evaluator declared that if they got Jackson, he would immediately be the franchise’s best athlete ever. Where Baltimore charted a new path was then building an offense unlike any the NFL has ever seen, around its best athlete ever.

“I’m going to tell you the impact that Lamar has had,” says Doug Williams, Washington’s senior VP of player development and the first Black QB to win a Super Bowl. “Unfortunately, you’re not going to get a Lamar Jackson every year. But the next Lamar Jackson that does come out, I don’t think the coaches and the scouts are going to sit around and say what he can’t do as a quarterback. They’re going to take a page out of Baltimore, and go back and get the tape and see what they did with Lamar Jackson, and use that. He has helped a lot of guys, especially young Black guys that are super talented athletically. He’s giving them a little more hope now, because of what he’s done.”

* * *

McNair Park in Pompano Beach, Fla., is located off NW 9 Ct, a street sign that also bears the name LAMAR JACKSON CT.

It’s hard not to tell that this is where Jackson grew up playing. Two of his Ravens jerseys are hanging in the lobby of the park’s rec center: A purple number 1, representing his first-round draft status, and a black number 8. The park is the home field of Jackson’s old youth club, the Pompano Cowboys, who each season award a Lamar Jackson Trophy to the best player in every age group.

This is where Jackson committed to playing quarterback, and where a network of young athletes in South Florida resolved to do the same.

When Jackson was eight, one of his youth coaches sent him to work with Van Warren, who leads the Cowboys’ 12-year-old team but had also made a habit of working with young QBs. “I’m not an expert by any stretch,” Warren admits, but he had thrown himself into this task out of frustration over seeing many of his Black youth players be told they wouldn’t make it as quarterbacks at the next level. He vowed to make their passing mechanics so impeccable that no coach could ever use that as a reason to deny them a shot.

This is how the Sunday training sessions, from 2 to 6 p.m. at McNair Park, began—Warren and Jackson’s mom, Felicia Jones, building a quarterback in the heat of the South Florida sun. Jones has been an unwavering advocate for her son, who has said she led him through the day he lost both his grandmother and his father, as well as his athletic career. On Sundays, they had a routine: Warren would work on Jackson’s mechanics, unafraid to spend 20 minutes solely on his three-step drop, and Jones would put her son through a core workout, insistent that would provide the balance he’d need to play the position. Perhaps the most grueling part was the rounds of 20-, 40- and 100-yard sprints.

When Jackson graduated from Boynton Beach High School, with a scholarship to Louisville, Warren assumed their Sunday afternoon tradition of the last decade was over. “No, we’re not done,” he recalls Jones telling him. “If we could do it for him, this shows we can do it for others.” So, they continued, together running a Sunday football clinic even after Jackson left for college, free of charge and open to any player willing to put in the same kind of work that Jackson did. Their goal is to help kids, some from economically disadvantaged parts of Broward County, earn a college scholarship.

They call their program “Super 8,” teaching both football skills and eight core values: God, prayer, faith, family, education, sacrifice, character and discipline. When Jackson changed from number 7 to 8 when he arrived at Louisville (“A new era,” Jones told Warren at the time, citing the Bible’s teaching that the eighth day of creation represents the new beginning) they had to add one more value. Fitting to Jackson’s path, the eighth one was faith.

Super 8 draws players of all positions, but Warren still devotes much of his time to the quarterbacks: One is 15-year-old Hezekiah Harris, which is how his dad, a high school coach and English teacher, first met Jackson and his family. Other regulars are 12-year-old Omari McNeal, who is motivated to win a Lamar Jackson Trophy for the Pompano Cowboys, and 16-year-old Luke Collins, a rising junior who aspires both to be a veterinarian and to play quarterback for a FBS team. Collins switched private schools between his freshman and sophomore seasons for a better opportunity to play QB; now he’ll be the starter at Blanche Ely, a public high school in Pompano Beach.

“Many coaches have tried to push me to play DB, and that’s not really me,” Collins says. “I could play it, but that’s not really where my heart was at. I have seen how [Jackson] was confident in himself, that this was what he was going to do; no matter what other coaches said, that he was a DB or receiver or running back, he stuck to quarterback. And I’m going to do the same thing.”

Jackson’s career brought both him and his mom to Baltimore, but they are still regular visitors to McNair Park, nestled between industrial facilities and Florida’s Turnpike. Jackson showed up one Sunday earlier this year, before the pandemic hit South Florida, and Warren stopped the workout, “which he never does,” Collins says. Collins posed for a photo with Jackson, who was smiling in the sun. Then, they all got back to work. On a different Sunday, Luke and his dad, Corey, listened to Jones talk to the group for about an hour. She shared how Jackson sacrificed going to parties to train, the importance of taking college admission exams early and her role in insisting to coaches that Jackson was a quarterback.

Jones’s choice to manage her son’s career, forgoing an agent, was questioned around the NFL before the draft, but she has become a beacon for parents who have seen their children’s hopes dashed each time a coach suggests they move to another position.

Three years ago, when Jackson was still at Louisville, Jones was a guest speaker at a football clinic in West Palm Beach. During the Q and A portion, one of the kids asked Jones, “What position is Lamar going to play when he gets into the NFL?” She replied that he’s always been a quarterback, and that’s what he’s going to be. Brandon Howard was in the audience that day with his son, Nehemiah. Brandon, who at the time was a sportswriter for a local newspaper, asked Jones for an interview, which she declined, as is her practice. But when he introduced her to Nehemiah and mentioned that he plays quarterback, she talked to Brandon as a parent: “You have to protect him and his dream.”

Nehemiah, who is 10, played running back until he saw the now-famous clip of Jackson hurdling a Syracuse defender during his Heisman season. “I thought, ‘I can do that,’ so I tried playing quarterback,” Nehemiah says. At age eight, after he had competed in the 100-meter dash at the Junior Olympics, a coach on Nehemiah’s youth football team decided to move him to receiver. The Howards switched teams the next year (coincidentally to the Miami Gardens Ravens), where the staff told Nehemiah he could play QB and wear number 8, like Jackson.

“I thought back to what Felicia told me, and I didn’t want him to lose confidence,” Brandon says. “I love how Lamar is dismantling all of those preconceived ideas about what a quarterback should be and how he should play. It opens the door for kids like my son to be able to freely express themselves and play the game the way that it comes natural to them.”

Earlier this summer, Joshua Harris noticed a new decoration in his son’s bedroom: Jackson’s towel had already been hanging on a mirror, and now a white piece of paper was taped to the ceiling. In red marker, Hezekiah had written win a state championship and drawn three empty boxes, one for each year he has left at St. Thomas Aquinas High. Joshua didn’t think much of it at first, but then he realized the sign appeared shortly after they had joined Jackson for his workouts with some of his Baltimore teammates.

Hezekiah explains, “Lamar never won a state championship, so he said, ‘You’ve gotta win one for me.’ I told him, ‘I got you.’ I put the sign on my ceiling for when I lay down in my bed, and I can always see it, to remind me that’s the goal.” A state title—as a quarterback.

* * *

Jackson has his own championship goals to pursue, in the city he’s invigorated in so many ways. Cia Carter, the owner of Miss Carter’s Kitchen, says she saw a 15% increase in business after she posted the QB’s visit in January. The fact that he and his teammates dropped by a Black-owned restaurant in West Baltimore, she says, represents the unique connection the majority-Black city has to its franchise QB.

“He comes from the same place that most of the kids in Baltimore City come from,” Carter says. “We can relate to him, we can feel him, we understand him and he understands us. How he talks, how he dresses, how he carries himself, how he plays—we connect with him.”

That ability Jackson has to connect—with young QBs in South Florida, with his new city, with his teammates—was undervalued in the predraft process, perhaps just as much as his passing ability. Williams has been around the NFL long enough to see a shift from 1978, when he was “Tampa Bay’s Black QB” after being drafted, to last year, when the playoff field had four Black starters under center. But in a league that is about 70% Black, the shortfall of Black talent evaluators and decision-makers means that biases persist in the grading and, ultimately, drafting of players. “They might not ask the right questions to find out who a kid really is, because they might be afraid to ask that question,” Williams says. “So you might not find out how well he can lead, or how he grew up, and what’s his mindset.”

Everything that teams missed about Jackson was on full display last season, whether in his spinning off and sliding through six Bengals defenders en route to a 47-yard touchdown run or telling Harbaugh “hell yeah,” he wanted to go for it on a fourth-and-2 in Seattle that turned into a touchdown. While he jokes that his play is “not bad for a running back,” he doesn’t strain to prove himself as a pocket passer, an unusual combination of both humility and confidence.

“The swagger that he plays with, and the swagger he has on and off the field, that’s something that isn’t super traditional for the quarterback position,” right tackle Orlando Brown Jr., part of Jackson’s draft class, said in January. “As a Black quarterback, he represents a lot. It’s something that we talked about. … He’s opened so many doors.”

But that is not top of mind for Jackson right now—not yet. Warren recalls a mantra that Jackson’s mom has often repeated: Talking doesn’t fix anything. His actions are what will provide a different answer to the same old questions, and he still has more to show.