SI Survey: Doctors Say They'd Play in the NBA and NHL, but not NFL and MLB

Professional sports are back, but are they safe?

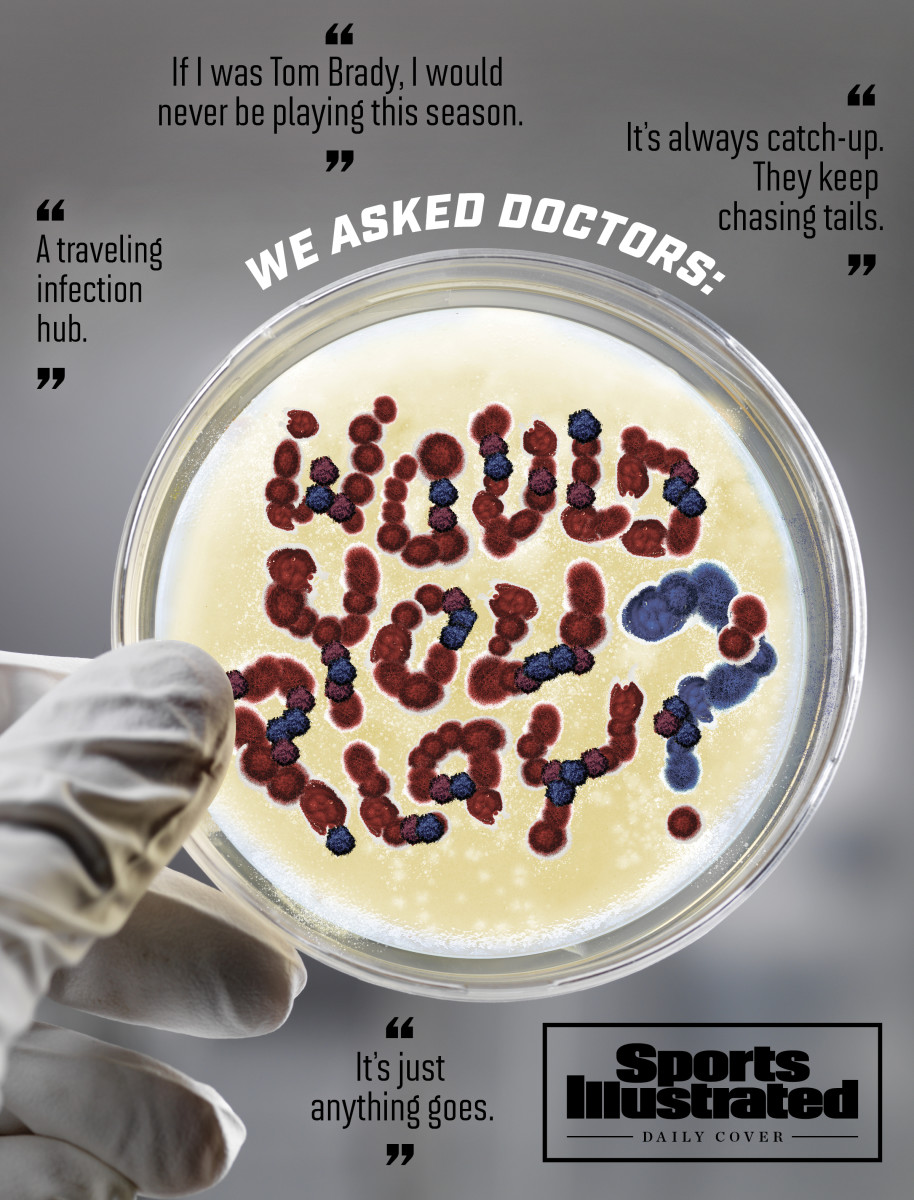

Leagues say yes. And the vast majority of athletes have chosen to compete. But doctors surveyed by SI tell a more complex story: They worry COVID-19 could cause many serious health problems down the road, and say that sports played outside a bubble are not worth the risk—even for young, healthy athletes who get paid millions to play.

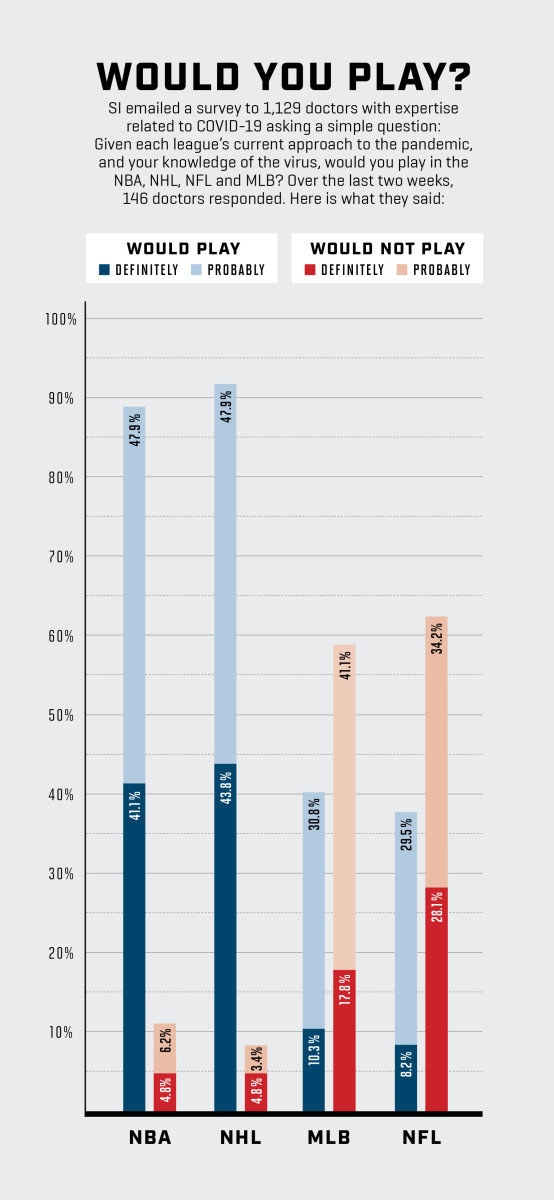

Sports Illustrated asked doctors with expertise related to COVID-19 around the country: If your full income came from playing in one of the four major U.S. men’s professional sports leagues, how likely would you be to play?

The results were stark. Roughly 90% of the 146 doctors who responded to SI’s survey said they would definitely or probably play in the NBA (which has built a locked-down “bubble” in Orlando) or the NHL (which has two bubbles in Canada). But majorities said they probably or definitely would not play in the NFL (62%) or Major League Baseball (59%) under current protocols.

One doctor called MLB’s plan “a traveling infection hub.” Several doctors said MLB’s COVID-19 outbreaks—which have forced 14 teams to postpone 42 games—were easy to predict. Yet doctors said they would be even less inclined to play in the NFL, which has a similar plan to MLB’s, but for a more physically intimate sport. Parveen Garg, a cardiologist at USC, echoed several other doctors when he said, “You’re going to run into worse issues than what MLB’s been facing.” Only 8.3% of doctors said they would “definitely” play in the NFL if their full income depended on it. Before training camps began earlier this month, 67 players decided playing wasn’t worth the risk, opting out of the season (compared with the six, 10 and 19 players who opted out of the NHL, NBA and MLB, respectively). In light of the turbulence MLB has already experienced, many of the doctors SI spoke to doubted that the NFL will be able to play its full slate of 256 regular-season games, plus the playoffs and Super Bowl.

Top medical officials for the NFL and MLB say the doctors we surveyed don’t understand or appreciate their protocols. “I think if you go to a facility and you see what is being done and then you look at all of the aspects of the protocol, you begin to realize the lengths we’ve taken to ensure the safety of everyone that’s involved,” says Allen Sills, the NFL’s Chief Medical Officer, who is also a neurosurgeon at Vanderbilt. Both leagues say that they expect some positive tests, but their rules are stringent enough to keep infections to a minimum.

They also say protocols will evolve as circumstances do. MLB has tightened its restrictions as the season has progressed; the NFL released new gameday plans just last week. Gary Green, MLB’s medical director and a physician in sports medicine at UCLA, says, “If we’re able to complete the season, then what we put in place was successful.”

Doctors we interviewed say the plans are still too risky. They disagree about the number of likely positives, and also about the gravity of each one. They all have backgrounds in epidemiology, cardiology, pulmonology or nephrology; they have studied disease spread and/or the potential long-term ramifications of COVID-19. Their answers spawn from two widely accepted principles in the scientific community: One is that if you don’t completely lock down, there will be outbreaks. The other is that, with COVID-19, what doesn’t kill you can make you weaker. The death rate for pro athletes who get the disease is very low, but there is a range of possible short- and long-term effects. Most doctors we surveyed are so concerned by the potential for health problems—and by how much remains unknown about the virus—that, even if they were offered millions to play football or baseball this year, they said they would probably stay home.

***

Benjamin Linas is an epidemiologist and associate professor of infectious diseases at Boston University. He is also a fantasy football team owner. Later this month, after his fantasy league holds its annual player auction, team owners will place side bets on when the NFL season will get shut down and which team will have the first outbreak. Linas—who said he would “definitely” play in the NBA or NHL, but would probably not play baseball or football—has a simple explanation for his skepticism.

“The reason is the bubble versus not the bubble,” Linas says. “The NBA and NHL have demonstrated if you really require it, you can do it.”

After some early positive tests and quarantines, the NBA and NHL bubbles have been virtually virus-free. Doctors mostly praised this system: They said that the strict lockdown should be able to keep infections at bay, and daily testing should catch any breach before it becomes an outbreak.

In Europe, where the virus is far more under control, many pro teams have been able to return to normal play and travel. But in the U.S., where the virus is still spreading rampantly, several doctors said anything short of a controlled clean site is probably doomed.

MLB eschewed a bubble largely for logistical reasons. “There's no place that has five major league fields within a half-hour drive,” says Green. “That's an ideal world, and it'd be great if we had a bubble and we had multiple fields where we could play and do that. But we have to operate in the real world.” He says MLB is considering instituting a bubble for the playoffs, when there are fewer teams to sequester.

The NFL’s Sills says his league has a “virtual bubble.” But other doctors say there is no substitute for an actual bubble. Shuta Ishibe, a nephrologist at Yale, says, “You just don’t know what everybody else is doing outside the [site].”

Baseball’s Marlins had an outbreak after (according to the team) players left their Atlanta hotel to get coffee. The Cardinals had one, as well. Most teams have had players test positive. The NFL has 32 teams, with 71 players on each, including practice squads, plus coaches and support personnel. Expecting that many people to be vigilant about social distancing for four months seems naive—and even if they are vigilant, there still might be outbreaks.

Efstathia Andrikopoulou, a cardiologist at the University of Alabama–Birmingham, says, “If you [live] at home, you have to control for not just who you are interacting with but who everyone else at home is interacting with.” She points out that the start of the NFL season coincides with the opening of the school year. Many schools are remote-only, but many are not. If NFL players follow every league protocol but still send their kids to school, they could expose their whole team to the virus. “Then it’s just anything goes,” Andrikopoulou says.

And even when the protocols appear to be working, teams are vulnerable to what UCLA pulmonologist Scott Oh calls “COVID fatigue.” As communities across the country have curbed the virus’s spread, people have often become less disciplined in social distancing and mask-wearing, leading to a resurgence. Athletes would be no less vulnerable to such a natural inclination.

Both MLB and the NFL spent extensive time developing comprehensive plans for the virus. But those plans, however well-intentioned, struck many doctors as incomplete, with too much focus on the games themselves. Gilbert Perry, a cardiologist at the University of Alabama–Birmingham, says, “The biggest risk is in the locker room and practice.” Critical-care doctor Scott Stephens of Johns Hopkins says, “It’s kind of sanitation theater. It probably doesn’t matter how quickly you clean the baseball. It matters how far you are apart from the guy who is infected, and whether you are wearing a mask.”

Stephens also says MLB’s up-to-48-hour lag time before getting test results reduces the effectiveness of testing. (MLB says it has been weeks since its lab took longer than 24 hours. The NFL has said it expects to receive results within 24 hours.) “You gotta dump water on it right away,” he says. “If you don’t, it’s going to explode in a hurry.” Linas says, “It’s always catch-up. They keep chasing tails.”

University of Washington epidemiologist Jen Balkus said she thinks it is inappropriate for leagues to devote resources to staging games while the nation fights the pandemic. But Balkus was the exception. Several doctors told SI they are huge sports fans and want the games back. They just don’t have faith in any plan that doesn’t include a bubble, and bubbles are hard to build.

“Baseball might be O.K.,” says Rich Krasuski, a cardiologist at Duke. “It’s a socially distanced sport anyway. It’s when somebody goes to a bar that you get in trouble. Football is not a socially distanced sport by a long shot, and it’s hard to bubble because of the size [of teams].”

SI did not survey doctors about college sports, largely because there are so many variables, with schools and leagues forming different protocols. (The Big Ten, Pac-12 and several other conferences have already canceled or postponed fall sports; several conferences plan to stage games despite outbreaks on numerous teams.) But Krasuski, who has season tickets for Duke’s football and men’s basketball teams, says, “I’m skeptical we’re gonna have a college basketball season.”

Stephens, the critical-care doctor, sees the NFL shutting down.

“I don’t have a crystal ball, but my guess is there is no way they finish the season,” he says. “I would be shocked. … [I’d be] happy to be shocked. It may not even be the players. It may be the referees. All the infrastructure people. The grounds crews. There is so much of a chance of a really significant outbreak.”

His pessimism about finishing the NFL season is widely shared. But that is not doctors’ main concern, and it is not why they answered the survey as they did. They have seen what the virus can do, they have suspicions about what it will do in the future and they are extremely determined not to get it.

“When you have lived this and taken care of these patients, it is very apparent how serious this is and how sick patients can get,” Stephens says. “All of us are really pretty careful about it.”

***

The national conversation about COVID-19 has often been framed around the death rate, creating a perception that patients either die or recover fully. Every doctor who spoke to SI painted a very different picture.

“One of the guys I work with got it in March,” Duke cardiologist Stuart Russell says. “He still gets short of breath walking fast. He’s a normal, healthy 40-year-old. And who the heck knows what it’s gonna be over the next 10 years?”

Linas says, “Just from patients I have taken care of, a month out, there is no way they would have been able to go back to an NFL career. They were short of breath going up a flight of stairs, and they did get better. [These are] generally fit people who had quote-unquote ‘mild‘ COVID, didn’t go to the hospital, and didn’t need oxygen, and a month later they’re still short of breath.”

Garg, the USC cardiologist, says, “I don’t think the concern would be, ‘I’m gonna get the virus and I’m gonna be in the hospital and die.’ That’s possible, but I think you’re also grappling with this possibility that the virus could induce permanent damage in your lungs or your heart. That would hurt your ability to be a professional athlete. You’d also be concerned for your long-term health. There’s some serious impact even on young athletes who get this virus.”

Concerns about long-term health issues, particularly related to the heart, were central to the Big Ten’s decision to cancel its fall sports season, including football. Yale nephrologist Shuta Ishibe says, “Of course death is the worst thing. But there are chronic things that you don’t want. … There’s a significant amount of patients who get acute kidney injuries from this virus. Oftentimes the ones who go into the ICU require dialysis. Most of them have good outcomes in the sense that their kidneys will recover, but would I want to be on dialysis? No. We don’t know if they’ll recover to baseline. If not, your potassium intake would be limited. That affects quality of life.”

Red Sox pitcher Eduardo Rodríguez had COVID-19 earlier this year and then developed myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart, ending his season. University of Chicago cardiologist Atman Shah says, “He may just be the first one.” A recent study of recently recovered COVID-19 patients showed myocardial inflammation in 60 of 100 participants, “independent of preexisting conditions, severity and overall course of the acute illness.”

This might be of even greater concern for some elite athletes than for the average person. Oh says that according to the CDC’s framework, even though NFL players are fit, many linemen are technically obese, which is a risk factor for complications from the virus. “Particularly linemen, who are in each other's space constantly,” he says. “The biggest players are at the biggest risk.”

Shah says the walls of the average U.S. man’s heart is between 0.9 centimeters and 1.1 centimeters thick. Elite athletes, especially larger ones, push themselves so hard that the walls often grow to 1.4 or 1.5 centimeters wide. When athletes retire, their biceps might atrophy, but the walls of their hearts do not. That increased thickness puts stress on the heart, putting them at greater risk for developing heart disease later in life. What happens if that athlete also gets COVID-19?

“We have no idea,” Shah says. “This is human experimentation on a scale we have never seen in our lifetimes. We have no idea what this does for reproductive abilities. We have no idea if there is a sterility effect—viruses in pregnant women have all kinds of effects. It’s easy when you’re 18 or 19 to say, ‘I’ll deal with it later.’”

It is also easy for a doctor to say, “I wouldn’t play.” Several of them acknowledged that the decision would be difficult. They tried to imagine themselves as healthy athletes with a relatively short time frame to chase a dream and all that comes with it. A seven-figure paycheck can change a person’s quality of life forever—even their life expectancy. But the flip side is that, if an athlete gets COVID-19 and loses even 5% of their long-term lung function, that could take the athlete from best in the world to fringe pro, depending on the sport.

Kamran Atabai, a critical-care specialist at the University of California–San Francisco who has treated between 50 and 100 COVID-19 patients, answered that he would “probably” play football. But there is a caveat: “If I was a young person and it was millions of dollars, especially in football [with short average careers], I think the risk-benefit ratio would probably make me play,” he says. “It’s not that I think it’s safe to play. If I had already made enough money to be fine forever and it was football, I wouldn’t do it. If I was Tom Brady, I would never be playing this season.”

Oh says, “If he's got a $10 million contract, it's like, You're rich versus richer—take the year off.”

Garg says, “I think the problem we’re running into here is we just found out about this virus, like, eight months ago. We have no idea what will happen five years from now or three years from now because we don’t know anyone who’s had it that long. All we are seeing is that this is not like the flu. There’s vascular inflammation that occurs. This virus actually damages the vessels in our body. We’re seeing things we don’t usually see. We can only speculate.”

As the pandemic has progressed, he says, he has become less concerned about the period of acute infection. Hospitals have become better at managing care for patients in the throes of the virus. But the more he learns about the long-term effects, the more worried he becomes.

“We’re seeing some sporadic case reports of people who aren’t shaking it,” Garg says. “We do CT scans of these people a few months later and find permanent changes in their lungs. We don’t have enough time to know what’s going on. So my concern level is unfortunately going up a little bit because we’re realizing that, whoa, there may be some stuff that isn’t going away.”

The NFL’s Sills says, “We’re certainly aware of potential complications of this illness, just as we’re aware of potential complications of other illnesses that our players can have. I think this is a risk-benefit calculation that every person makes for themselves. For me personally, I would have no problem with playing under the current protocols.”

***

On Sept. 10, Michael Matthay is scheduled to testify via Zoom before the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The topic: various possible long-term effects of COVID-19.

Matthay, a pulmonary specialist at University of California–San Francisco, says, “We don’t have the data yet on long-term effects. You generally need at least a year to see.” But some COVID-19 patients develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and Matthay helped lead a study of ARDS, which was published last year. His team found ARDS patients “have consistently demonstrated a decrement in physical function” and that “long-term complications remain common and problematic for survivors.”

Matthay is a huge sports fan. He has attended seven Red Sox fantasy camps. He told his wife, when Giants catcher Buster Posey was weighing an opt-out, “This is a bigger decision than you realize.” He understood that Posey probably needs to add to his counting stats to make the Hall of Fame.

“Listen, I love sports,” Matthay says. “But I’m also a physician.”

If he were 23 years old and could make $10 million playing in the NFL this season, would he?

“I would not.”

Seven hours after Mattay testifies, Kansas City and Houston are scheduled to kick off the NFL’s 101st season before a limited crowd—up to 22% of capacity—that is supposed to socially distance. Chiefs lineman Laurent Duvernay-Tardif will not be on the field that night. He holds a doctorate in medicine, he has helped fight the virus at a long-term care facility in Quebec this offseason—and he has elected not to play football this year.