The Impossibilities of Russell Wilson

Russell Wilson has agreed to shed some light on “Russell Wilson Things”—the ironically generic term we’ve coined for the freewheeling circumnavigation of defenders who have advanced deep into Seattle’s backfield. The plays that seem increasingly doomed every time Wilson turns his back to the defense.

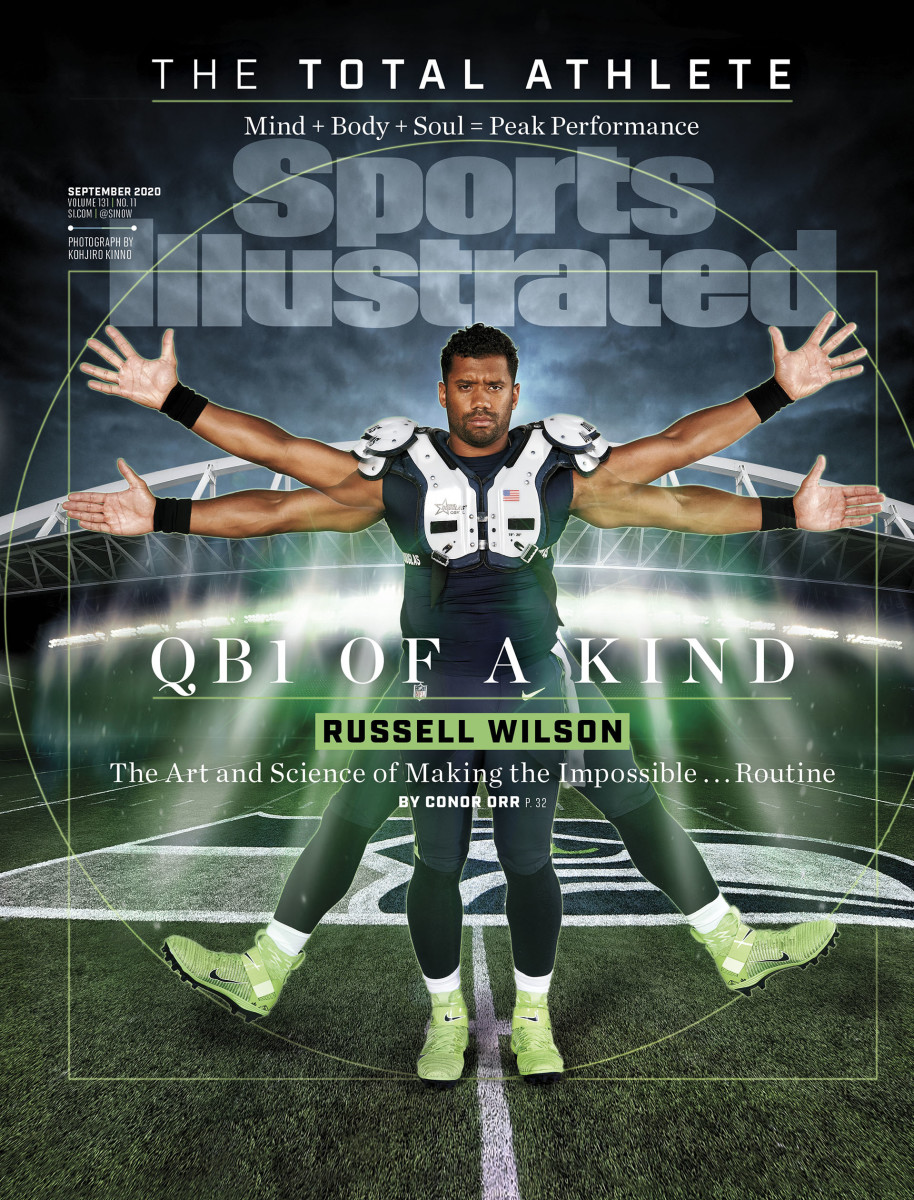

The plays that seem biomechanically impossible but that, in reality, become uniquely more possible given Wilson’s college-linebacker physique. The plays that end, typically, with some version of a blind jump hook over a towering defensive end’s head, the ball landing in the arms of his receiver.

Jake Heaps, Wilson’s former teammate and now his personal QB coach, likes to think of this all as art. Wilson, he says, like Picasso or Van Gogh, was, thankfully, never chided for coloring outside the lines. He adapts, survives and then thrives in a way that is both unusual and beautiful. For Decker Davis, personal trainer to both Wilson and his wife, the singer Ciara, these plays represent a devotion to craft, the culmination of a workout plan. Davis and the QB re-create unusual football scenarios in strange places, searching, for example, for the hottest, deepest sand in Rio de Janeiro to practice throws and spinouts in the middle of Carnival. Something about that sand, Decker says, wears you out faster.

Maggie Catlin, a physical therapist at the University of Washington, watches Wilson and sees a marvel of motor control, a quarterback who moves unlike anyone else at the position.

On the eve of a season to be headlined by the next great class of quarterbacks (Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson, Deshaun Watson) and that will kick off the farewell tours for any number of aging greats (Brady, Brees, Big Ben, Rivers, Rodgers), where does Wilson, with his incredible theatrics, fit into all of this? Those close to him insist he’s long been crafting improvisational masterpieces while the rest of the football world remained enamored with the pocket quarterback elite. Then he sharpened his pocket game at a time when those same people started obsessing over the mobility and theatrics of today’s young stars, as if they were something new—something we’d been missing all along.

Is it possible that the essence of Russell Wilson—voted by his peers as the NFL’s second-best player in 2019, yet never the recipient of a single MVP vote; overshadowed by Seattle’s Legion of Boom defense on the front half of his career and by a new generation of stars on the back end—will go forever underappreciated?

Perhaps a look inside his mind while he relives these “Russell Wilson things” (over video conference call; it is still 2020) might spur one to reconsider the natural order of things. It is a cliché: the player who enters a new season believing it will be his best. And still it’s worth noting: Those close to Wilson believe there is something truly special on the horizon, the coronavirus be damned. Something that will elevate these little moments of football genius to a more appropriate level of appreciation.

* * *

Wilson appears, through the magic of Zoom, in a sparsely decorated office inside his Seattle-area home, having just come from the nursery down the hall. He is in a brief pre-training-camp quarantine after the birth of his son, Win, which means he’s not exempt from changing diapers.

Video is queued up on our shared screen, and there he is, escaping from Jared Allen. We’re in the middle of a frantic Seattle comeback—one that will ultimately fall short—in a playoff game at Carolina five seasons ago. The Seahawks face third-and-goal, the shotgun snap is from the three-yard line and Wilson starts to roll right, per the play design. But almost immediately he’s headed straight backward, Allen having broken through the middle of the offensive line. With Wilson’s receivers smothered in man coverage, the QB is forced to conjure up new reserves of space and time.

This play, Wilson says, is about presence—the ability to see beyond what your mind is alerting you to. In this case: the 270-pound man charging straight at you.

“A lot of people want to look at Jared right here,” Wilson says. “Me, I want to keep my eyes downfield. That’s the magic of it all, to be able to see these things as one big picture.”

In his mind, he is eight years old, weaving through the Regency Square Mall in Richmond, where he grew up. He remembers navigating those floors, trying to keep his eyes focused on his destination and not on the hordes of bodies and swinging shopping bags in his path. He would spin and juke, developing a sense for the flow of the oncoming masses, and he’d feel the open avenues without staring them down. “People were probably like, What is this kid doing?” he says, laughing.

Back on the screen he spins, momentarily turning his back on the play, to create more space, drifting past the 20-yard line. He says he remembers making the decision, finally, to unleash the ball the moment that safety Kurt Coleman, lurking deep in the center of Carolina’s defense, committed to a different receiver—a ridiculously subtle movement.

Asked how such a small twitch could trigger a reaction, Wilson lands on a basketball metaphor. As a point guard, he says, “you don’t just watch one player, you watch the orchestration of the play. Where people are. You have to study the paint.” The pass he ends up throwing on our particular play? Wilson says it’s a football version of a fadeaway jump shot. He remembers first attempting something like this at Collegiate School, his prep school in Richmond, against Godwin High, to a receiver named Spencer Robinson—a fact he recalls with a peculiar ease. Now he practices it with regularity.

Wilson’s release movement is both a pirouette and a hip torque, resulting in a perfectly floated, near-blind pass to Jermaine Kearse in the back of the end zone. The ball travels just over the outstretched fingertips of cornerback Josh Norman, then at the peak of his powers, and into the hands of Kearse, who follows with a short celebratory quarter-hop in the end zone.

Russell Wilson is ridiculous. pic.twitter.com/h28DR9W6TQ

— Troy Machir (@TroyMachir) January 17, 2016

The way Wilson puts it: Yes, his is a lifestyle of training and mental preparedness (he compares himself to both a race car, needing constant tweaks and repairs, and that car’s driver), but that all blends with the carefree spirit of a kid bobbing and weaving past Foot Locker and Spencer’s. In the process of describing this one play, Wilson references childhood experiences as a mallrat, as a high school point guard and as a shortstop extending for a ground ball lashed up the middle of the infield.

His origin story and narrative are tightly anchored to this theory that kids should be outside playing all different sports; it’s something he comes back to often. In sixth or seventh grade he was primarily a baseball player when he was rushed into his first organized football game, playing quarterback without any knowledge of the playbook and leading his team to a 50-plus-point victory. Before transferring to Wisconsin, where he’d focus during his final collegiate season on football, he also played baseball at North Carolina State. He was a fourth-round pick by the Colorado Rockies, spending two seasons in the minors, and later he attended spring training with the Rangers and the Yankees.

His multisport athleticism, plus the repetition of that fadeaway throw—it’s second nature to him now.

“A great shortstop is natural,” he says. “I always want to make it look easy. I’ve always wanted to make throwing the football look easy and effortless.”

* * *

Davis, the trainer, and Heaps, the personal QB coach, each describe having to create new drills tailored specifically for Wilson, because no one plays quite like him. In one such exercise, Davis will have the quarterback stand one-legged on a spongy Airex balance pad, or on an inflatable Waff ball, and then Davis will toss a three-pronged HECOstix at the QB. Each prong of the stick is colored differently, and Wilson will have to catch it by whatever-colored handle Davis calls out. The goal: force Wilson to zero in on his task, despite whatever uncomfortable or unusual thing Davis throws at his body.

Heaps, honing Wilson’s gift for dropping high-arching rainbow passes with pinpoint precision, frequently has the QB chucking balls over a goalpost, simulating the peak of a defender’s outstretched hands, toward a target.

Which brings us to the second “Russell Wilson thing,” from a 2017 Thursday-nighter in Arizona, executed by a quarterback who’s figured out what he’s capable of doing, refined his mind to trust it and hired a maniacal training staff to sharpen his unique tools—his outlier skills.

On tape the Seahawks are protecting a 15–10 lead early in the fourth quarter, sitting at their own 44 facing a second-and-21, trying to claw back from consecutive penalties by the offensive line—holding and false start—to begin the series. The play is called “Smash” and it incorporates a naked bootleg, meaning that Wilson, taking a shotgun snap from the right hashmark, will fake a handoff and roll left, toward the open side of the field, with almost zero protection. No one is immediately open, and the QB is forced to hold the ball.

Receiver Doug Baldwin, originally charged with delivering some “get in the way” blocking, realizes that the play is in trouble. He releases to get open, freeing up defensive end Chandler Jones, whom Baldwin had been occupying at the line, to sprint at Wilson.

The quarterback, in turn, makes a hard step toward the sideline, then spins backward, causing Jones to wobble slightly and slow. Meanwhile: Safety Tyrann Mathieu, sensing an opportunity to pin Wilson in the backfield, rushes in and leaps behind Jones, as Wilson tries to square his body to throw.

In reaction, Wilson pulls the ball down and spins backward again—he is almost 20 yards behind the original line of scrimmage—and both Jones and Mathieu, still closing, split up and shut down two available rushing lanes. A third Cardinals defender, defensive end Olsen Pierre, is coming from Wilson’s right, blocking that escape route.

“People don’t understand,” says Wilson as he watches it all unfold. “For me—right here—the game is suuuper slow in my mind, because I’ve done this before.”

Wilson has twice now turned his back on Jones, one of the most prolific pass rushers of the past decade. But while doing so he is getting narrow, split-second glimpses downfield and accounting for his most dependable receiver, Baldwin, as well as the defender situation in his vicinity (the mental processing). Dana Bible, Wilson’s football coach at N.C. State, says he’s never met a player before or since who can essentially count moving pieces while blindfolded.

“I know [Baldwin] is still there,” Wilson says, “so when I do one more spin move to free some space and make [Jones and Mathieu] move, that’s when I knew I would give Doug a chance.”

After the second spin, Wilson hurls his body into a fadeaway motion and lets the ball loose. On the broadcast, NBC play-by-play man Mike Tirico says “cue the circus music” with the casualness of someone who’s seen this all from the quarterback before. Wilson lofts the ball toward Baldwin, who’s stationed at the Cardinals’ 48-yard line, near Antoine Bethea. The Cardinals’ safety, then 33 but participating in the kind of play the likes of which he could have never prepared for, mistimes his leap and falls to the ground as the ball lands in the grasp of Baldwin, who chugs 40-odd yards downfield to Arizona’s two-yard line.

Russell Wilson's 54-yard Pass to Doug Baldwin

— Football America 🏈 (@FB_America) November 10, 2017

🔥🏈🔥🏈🔥 pic.twitter.com/vYIO4xoHe9

The broadcast feed, meanwhile, zooms in quickly enough to catch Wilson’s face, which resembles a marathon runner patiently and comfortably slogging through the waning moments of mile 23. Wilson admits that he’ll sometimes smile when he does Russell Wilson things: “I’ll say, ‘That’s pretty sweet.’ ” But let that not be confused with self-assurance; the quarterback is merely accustomed to his own otherworldly body control. Russell Wilson things belong to all of us, not to the person who has formulated himself to make them routine.

* * *

“Let Russ Cook.” Scroll through Twitter on a Seahawks gameday, and that, roughly, is the typical plea from fans, aimed at coach Pete Carroll and offensive coordinator Brian Schottenheimer. Carroll’s goal, it can seem, is to call the most balanced offense in football. In 2019, only five teams passed on a lower percentage of plays than Seattle (54.0%), and in ’18 no team threw less frequently. The team went to the playoffs in both of those seasons, in large part because Wilson consistently delivered his heroics late. According to the analytics site FiveThirtyEight, the ’19 Seahawks played six “coin-flip” games, in which the win probability for both teams was 40% or greater within the final five minutes of regulation. The Seahawks won five of those games. Of their 12 wins between the regular season and playoffs, 11 of them came by a one-possession margin.

Of the three plays on our docket, the last one, from the 2019 opener against the Bengals, may be the least overtly spectacular. Which, in a way, speaks to the point: Russell Wilson things have become commonplace.

On our screen, Seattle trails Cincinnati 17–14 in the final minute of the third quarter. On third-and-five at his own 41, Wilson stands alone in an empty shotgun set and upon receiving the snap briefly surveys five eligible receivers running intermediate routes near the first-down marker.

“They’re in a jam front,” Wilson says of the defensive alignment, “so they have five guys up front, then they drop two. They’re really rushing three dynamic rushers and dropping two really great rushers so they can spy me. They have two spies.”

Despite that limited pass rush, Wilson immediately gets pressure from his blind side and begins to flee to his left. He ducks into a narrow inlet that develops in the sea of bodies, stepping up into what appears to be a clean pocket to reassess his reads or perhaps make a run for the first down. But the defense—those spies—is prepared for this eventuality, as 6' 6" defensive end Carlos Dunlap and 6' 1" linebacker Preston Brown are waiting for him. “Like stepping into the lane and seeing Dikembe Mutombo,” Wilson says.

Catlin, the UW physical therapist, compares what she’s seen of Wilson to some of the other great modern quarterbacks. She says that, on a given play, his body goes through an entirely different process than, say, Aaron Rodgers or Tom Brady experiences. Specifically: For Wilson, throwing on the run is truly throwing on the run.

“If Aaron or Tom wants to throw on the run, their bodies have to create an entirely new motor plan—a new task,” Catlin says. “Russell doesn’t need to switch tasks. He can use the same motor plan.”

From a biomechanical standpoint, she says, for an athlete of Wilson’s stature (a shade over 5' 10 1/2" at his NFL combine weigh-in and 215 pounds), success boils down to an ability to adapt. “For some, their body just can’t figure out how to [succeed]. Then there’s this other group of people who have this crazy ability to adapt to a situation. Their body will find a way, even if it’s not the motor plan that you and I would have picked. Adaptability is the word we use all the time.” Wilson has, in a sense, adapted and become something more evolved.

As that one play unfolds at CenturyLink Field, Dunlap and Brown represent just one of Wilson’s problems. Another: Even this late in the down, there are no good options available downfield. The best of them is rookie D.K. Metcalf, who, working the left side of the field, finally has a step on his man—but any throw would have to be calibrated so that it a) drops in over that defender but b) also arrives before Metcalf reaches the heavy traffic waiting for him downfield.

Reliving the play on his computer, Wilson brings up his mental coach, Trevor Moawad, whose clients have also included Deshaun Watson, Eli Manning, Alex Smith and the Alabama program under Nick Saban. Moawad’s work centers on building a “neutral” mindset and the idea that eliminating persistent negative thought is more important and effective than encouraging persistent positive thought. He has programmed Wilson, in a sense, to stand in front of two much taller oncoming players with all of his receivers covered and think about the situation in the following way: Just throw it up. Alley-oop. It will work. And not: Metcalf is in his first NFL game. If I loft the ball to him with enough air under it, it may reach him, but so will Bengals safety Jessie Bates, who can cover 10 yards of field in 1.58 seconds.

Ball still in hand, Wilson gears down slightly, peeking around Brown to spot a thin slice of field through which to aim just before he lets loose a touch pass. Bates, meanwhile, begins a full diagonal sprint toward the receiver, crashing into Metcalf—still midair, reaching for the ball—but he is too late. Metcalf secures the ball, and Seattle has 25 must-have yards on a crucial third down.

This Russell Wilson to DK Metcalf relationship is developing strongly. What an awesome catch and adjustment to reel this one in. Great placement by Wilson too (again)! #Seahawks pic.twitter.com/BNb2VBVffh

— Samuel Gold (@SamuelRGold) September 8, 2019

Two snaps later, Wilson will open the fourth quarter with a 44-yard touchdown to Tyler Lockett, the eventual game-winner having been set up by a Russell Wilson thing about which no commercial will be made.

“I just turned 31,” Wilson says. “I’m right at the beginning of my prime. I have so many more years left. At least 10-plus years left. I’m just getting started. That’s the fun part for me. My goal is to play another 15 years.”

Those in and around football speak often about the difficulties of engineering a great quarterback, the perils and obstacles along the way. They struggle with the burden of being a franchise quarterback. They grow cynical. They get hurt. They get minimized by unimaginative schemes. But what if we missed a blueprint that has been right in front of us for eight years now? What if Wilson’s approach—the way he has contextualized his experiences across multiple sports, engineered his strengths, maintained his creative freedom on the field and cemented a narrative of success in his mind—is the way to build the quarterback of the future?

What if these Russell Wilson things are just a prelude to something bigger for him, and players like him? He takes in that key third-down play against the Bengals, and what he says could apply, essentially, to anything in his life at this moment: “It becomes who you are, in a way, once you believe it.”