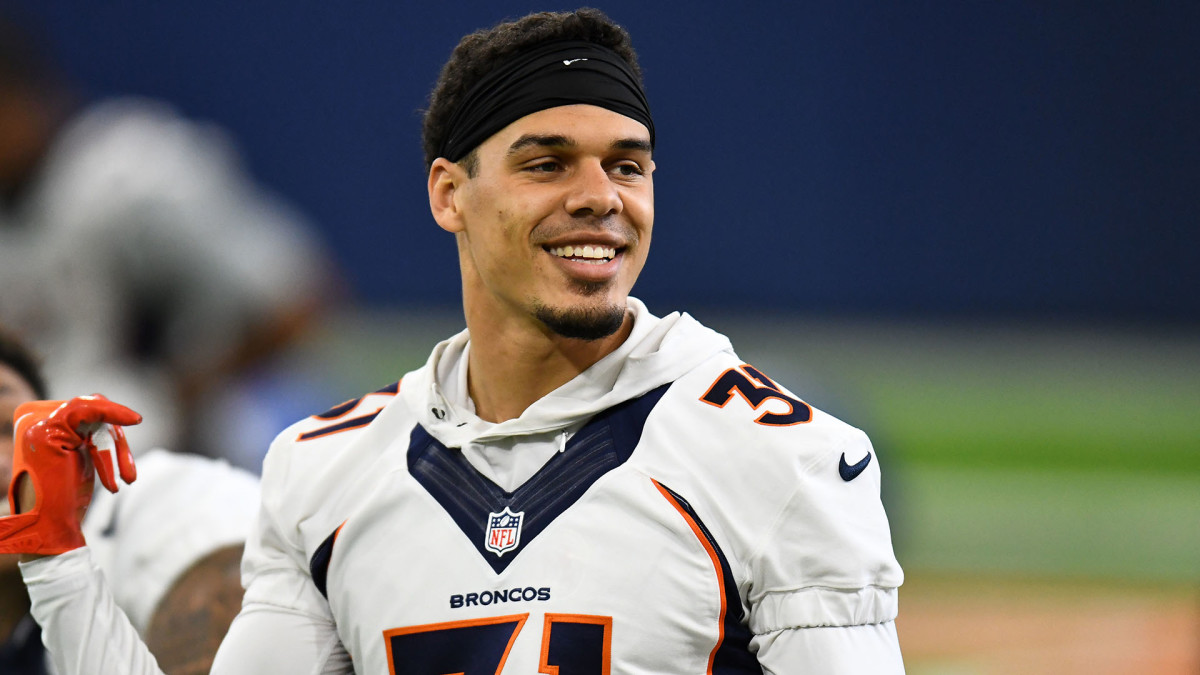

How Justin Simmons Found His Place

Before his third NFL season, back in 2018, Justin Simmons decided to drive to Broncos training camp from his home in southeast Florida. Somewhere along the highway in Colorado, his wife, Taryn, took the wheel so her husband could catch a nap. She was carrying the couple’s first child, a daughter, and keeping an eye on the family dog in the backseat.

That’s when she heard the sirens.

Two policemen pulled the Simmons family over. The one that stopped at her window asked Taryn to get out of the car. As the other one approached her husband, his right hand never left the gun holstered on his hip. “Every time a cop has pulled me over, that’s always been the case,” Simmons says. He placed both hands in front of him on the dashboard, told the cop he didn’t have a weapon and spoke only when directed to.

The first officer pulled Taryn aside, away from the car, relaying his concerns. They didn’t relate to traffic violations but instead to her personal well-being, the implication as clear as the blue skies overhead. She explained that she was married. And pregnant. And riding in the car with her husband. That cop continued to ask what Taryn calls “weird questions.” Like, are you safe? Finally, she did the only thing that she could think of. She told the cop that the man being guarded in the passenger seat started at safety for the Denver Broncos. The officers’ tones and demeanors changed, abruptly, in that instant. “What number is he?” they asked, saying they’d have to root for him. Then they let the Simmons family go without ever saying why Taryn had been pulled over.

Taryn, who is white, and Justin, who is biracial, saw the encounter through the lens of their respective life experiences. To Justin, it was normal, the routine of being pulled over by police. The incident terrified Taryn, though. Yes, her husband did play for the Broncos. Over the next two seasons he would become a star, making second-team All-Pro in 2019. But, she wondered, why did any of that matter on the highway? What if he didn’t play for the Broncos? What was the worst-case scenario? “I was shook up for a long time,” she says.

“What if I had lost him?”

* * *

Now, two years later, on the eve of another season, Justin Simmons has decided he can no longer stay silent. He’s 26, established, secure and, like many across the U.S., he wants to address systematic racism and economic inequality, issues that he saw from two different sides while growing up in Stuart, Fla.

His mother, Kimberly, is white. His father, Victor, is Black. They’ve been together for 36 years, married for 28. Even the idea of their union wasn’t easy for their families, especially at first; there were many who supported them from both sides, but others voiced their opposition. Justin, the oldest of three brothers, says he never felt comfortable on either side of the line that his relatives had drawn. He never felt white enough, never felt Black enough. “I always felt out of place,” he says.

His father taught him to react just as he did on that highway in Colorado. Victor always reminded his boys that even when he was wrong, they should consider him to be right. The same notion, he told them, applied to anyone in law enforcement. The goal never changed. It was to get home safe, alive. “Any time you get pulled over,” he told the boys, “do exactly as they say.”

The parents Simmons learned from had their own experiences, how race changed the way that people acted toward them, from the beginning of their courtship. As they headed toward the door at the end of the first college party they’d ever attended as a couple, they were intercepted by a group of officers. They asked Kimberly whether she was O.K. and told her to head home. Then they cornered Victor and his friends and started asking questions. “I’m not leaving until he does,” Kimberly told them, gesturing at her future husband.

Kimberly saw those kinds of differences in interactions for the rest of her life. They’d often be pulled over for no reason. The cops always placed their hands on their guns. One time, her youngest boy, Tristan, asked the officer, “Why did you pull my dad over? He didn’t do anything wrong.” The cop mentioned something about a stop sign. They had stopped, all right, but an inch over some sort of line.

The Simmons’s took an honest approach to parenting in that environment. They didn’t hide the world’s problems from their kids. They told their children that racism was everywhere, that they would be forced to confront it and that they should handle the worst that society threw at them with dignity and grace. They didn’t have to be white. They didn’t have to be Black. They were both, Kimberly said, a beautiful mixture.

Sports helped Justin Simmons find himself and find his place. His father had made it to the fringe of the NFL and, in his oldest boy, he saw a more athletic version of himself. Justin’s career ascendance was steady, measured, much like his personality. He was a three-star recruit whose best offers came from Boston College, Purdue and Illinois. He chose BC, carved out a role on special teams early and later became a starter then an all-conference selection.

Before his senior season, Justin sat down with Taryn to discuss their future, saying he hoped for a chance to make an NFL practice squad that spring but would put their family first if he couldn’t stick. Instead, he played so well for the Eagles that he went on the draft’s second day, at the end of the third round. Fittingly for a player so reserved, he missed the party his family had planned for the final day of the draft, when he was en route to Denver.

He joined a fearsome defense that had just dominated Super Bowl 50 against Carolina, shutting down Cam Newton, Tom Brady and Ben Roethlisberger in the playoffs. That next season, in 2016, Simmons watched as 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began to kneel for the anthem. Simmons reacted like many across America; he wondered why Kap had to kneel then, he didn’t want to disrespect the flag. But rather than condemn Kaepernick, Simmons started researching what the QB stood for, how he knelt to draw attention to systemic racism and police brutality, how his protests were peaceful and unrelated in any way to the military or the flag itself. “Protests aren’t done to make you feel comfortable,” friends told him.

Simmons did not yet feel comfortable expressing what he’d learned in public forums, but he leaned on teammates like linebacker Brandon Marshall and wideout Demaryius Thomas. They schooled him about the need for conversation around these issues, for voter registration and widespread criminal justice reform.

He listened, then dove deeper. While he did, he cemented his place in the NFL. He became a starter in ’17 and never relinquished his position. Teammates began to compare him to Damian Lillard, the star guard for the Portland Trail Blazers who tends to wind up on lists for the NBA’s most underrated players.

Then Vic Fangio became the Broncos’ coach before last season, and he tasked Simmons with additional responsibility. Fangio turned Simmons into the Broncos’ answer for Tyrann Mathieu, one of the league’s most versatile players. Simmons lined up deep on both sides of the field, while moonlighting at corner, nickel and dime linebacker. As part of one of the NFL’s best safety tandems with Kareem Jackson, he helped the Broncos recover after an 0–4 start. Denver’s D held opponents to 18.6 points per game over the final 12 games, sixth-lowest in the league during that span, and Simmons joined Mathieu as a second-team All-Pro.

After his rookie deal expired, the Broncos could not reach a long-term agreement with Simmons; they slapped him with the franchise tag instead. He took the same measured approach as always, noting how far he had come—and not just on the field.

* * *

In this most unusual off-season, Simmons decided he could no longer remain silent on the issues that affected him, his teammates and Black men in the U.S. He had long conversations with Jackson and pass rusher Von Miller about social justice initiatives, building on what he had learned from Marshall and Thomas.

It took Simmons the better part of a day to force himself to watch the full video of when police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, kneeling on his neck for almost nine minutes. It hurt Simmons to scroll through his social media, to read that many in his hometown felt that Floyd deserved what happened to him, or made excuses for the officers, citing his lack of cooperation or the presence of drugs in his system. Simmons wanted to scream that none of that mattered, that no one deserves to die like that, with the world watching, and that what happened to Floyd has happened to Black men in the U.S. with alarming regularity for far too long. He kept thinking back to that traffic stop on the way to training camp, how that could have been him lying on the pavement. The reaction to criticism of Floyd marked a final push toward advocacy, the public kind. “I just started tearing up,” Simmons says. “I had to say something.”

Despite the anger he felt inside, Simmons believed that he could impact discussions on social justice by simply sharing his dual perspectives as a “biracial human.” When Fangio stumbled into controversy by saying he didn’t believe that racism existed in the NFL, Simmons tried to understand where such ignorance came from. He believed his coach to be sincere, if not misguided. “I think he really believed that,” Simmons says. “Call me old-fashioned or naive, but I truly feel that people mean well. And I truly believe that, to move forward, to have important, healthy conversations; we can’t just bash people.”

The safety encouraged that kind of dialogue with his teammates, strangers, anyone who’d listen. He called for voting and criminal justice reform. When demonstrators gathered in his hometown, he joined them, alongside his parents, and was handed a megaphone to speak. He hadn’t planned on saying anything. But he addressed the crowd from his heart. He said, “We pledge our allegiance to our flag for freedom and justice for all, and we do not have our justice. But we will get it. But we will not get it by force.”

He joined Miller, Jackson and Fangio in Denver, demonstrating with thousands who marched through the streets. He spoke there, too, and as his mother and wife watched news accounts, they saw the culmination of all the life events that led Justin to that moment. They saw the difference he could make, the empathy he asked for. They were proud. “We all knew that voice was in him,” Taryn says.

Now, the person who, four years ago, wondered why Kaepernick knelt is considering kneeling for games this season. The Broncos, he says, will make a decision as a team. Either way, he says, “We’re all better off for the conversations we had this spring and summer.” Justin and Taryn’s daughter is almost two now, and they plan to have the same conversations with her that his parents had with him.