The Kelce Brothers Fuel Each Other’s Greatness

The Kelce brothers disagree.

In a Zoom call days before training camps get underway, Jason, the Eagles’ 10th-year center (positionally and spiritually), recounts the good fortune he’s had to play most of his NFL life in Andy Reid’s and Doug Pederson’s inventive offenses, which have allowed him, at a relatively light weight, to serve as a roving fulcrum rather than a straight-ahead masher. “If I was on 25 other teams in the league, trying to run the plays that they’re running,” he says, “I’d probably be an average-at-best center.”

Travis, the all-everything tight end for the Chiefs, is having none of his older brother’s modesty. “He’s gonna find a way to have success,” Travis says. “He’s a tricky sumbitch now. Don’t get it twisted. He knows how to play this game. And if it was a different style of game, he’d figure that one out too.”

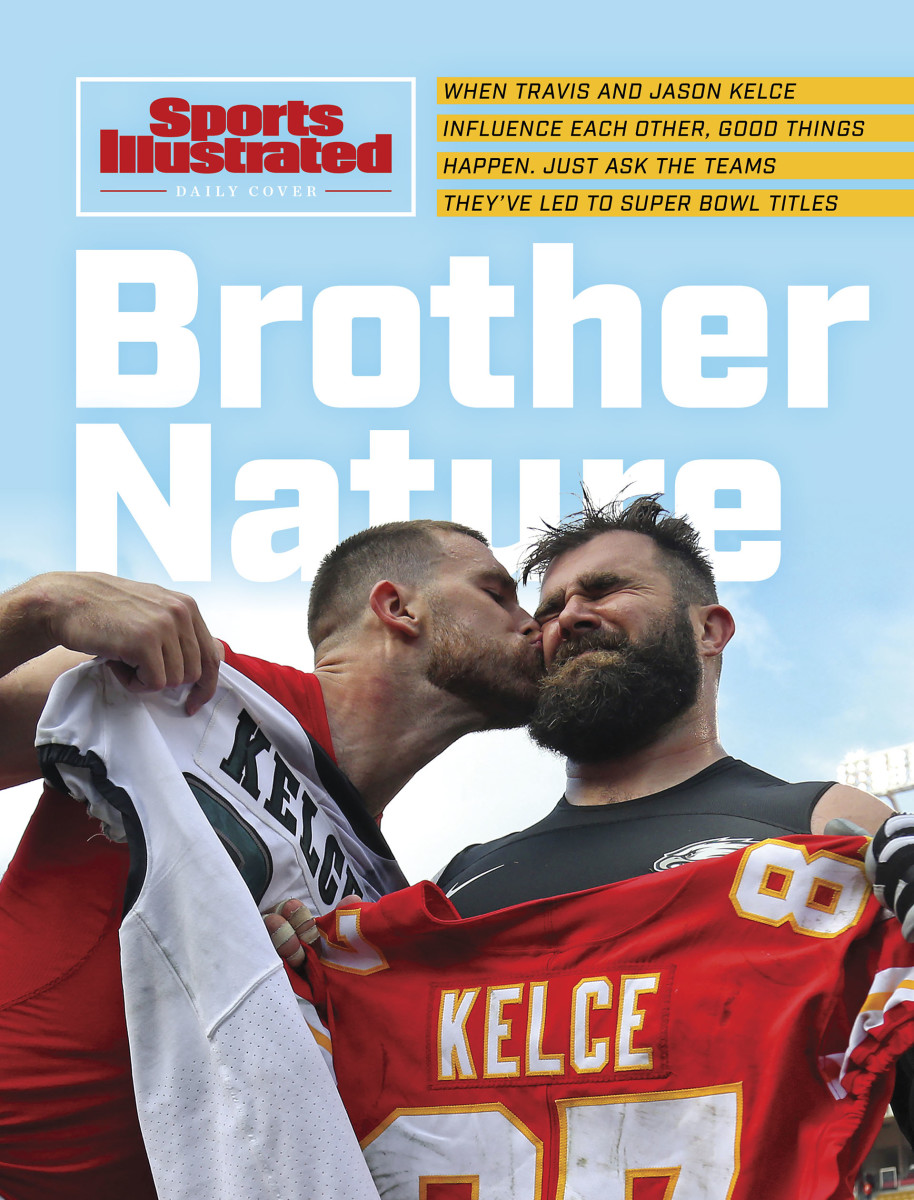

The fraternal resemblance between the two would be apparent even to anyone unfamiliar with their on-field exploits—vast jawline; hull of a forehead; scanning, football-schooled eyes—but, even beyond this small bit of sibling contrarianism, they broadcast vibes all their own. During the coronavirus pandemic Jason has settled into his preferred look: a dark and stately mullet, shoulder-length, balances a beard that could absorb a head butt from a nosetackle; aggressively unkempt eyebrows reside in between. Travis, who in the days before the call has run through a standard-for-him gamut of GQ and TMZ cameos, is cleaned up, his hair cropped in close waves at the top and buzzed tight at the sides. His own beard, light brown, is manicured and oiled. He wears looped, diamond-studded earrings.

“I just let him do his thing and watch from a distance,” Jason says of Travis’s fondness for the trappings of NFL fame: He has recently partied preshow with Post Malone and celebrated Kansas City quarterback Patrick Mahomes’s record contract extension on a boat in Lake Tahoe. The brothers recall Travis’s short-lived E! dating show, 2016’s Catching Kelce; it took a substantial amount of persuasion to coax Jason into making just a couple of on-screen appearances. “Even as he was on the show,” Travis recalls, “it was just kind of like, Dude, you’re an idiot.” Jason jumps in with a loving concession: “Yeah, it ended up being a lot of fun, though.”

With apologies to the Watts, the Kelces stand as the most accomplished siblings in the NFL. Since 2011, Jason’s rookie season, the two have garnered a total of eight Pro Bowl appearances and five All-Pro nods. Travis, 30, already has the league record for most consecutive 1,000-yard seasons by a tight end, with four; as the too-big-too-fast trump card in the Chiefs’ offensive hand, he’s a safe bet to add more. The 32-year-old Jason, who makes up for being 6' 3" and not-quite-300 pounds by running a 4.89 40, has been Pro Football Focus’s top-ranked center the past three years. The brothers have suffered only three losing records in a combined 18 seasons (all Jason’s). They’ve won two of the last three Super Bowls.

Each is adored in his city, and each is widely understood as the inverse of the other. Jason: cutthroat, spotlight-averse, selfless in the extreme. Travis: chatty, flashy, lavishly gifted. But if the shorthand is accurate enough for pregame TV fodder on Sundays, when the two make for convenient avatars for their teams’ broader identities, it also obscures a more layered relationship. The brothers share a profound belief in what makes up winning football—passion, leadership, curiosity, smarts, love—and each contends he wouldn’t have found his championship formula without the other.

* * *

Seven seasons in, Travis has successfully distanced himself from the antics of his early professional career, when sparkling plays—shutter-quick breaks in post and dig routes, highly improbable midair adjustments—were too often negated by taunting and excessive celebration penalties. “All the negatives, the flags for the personal fouls and silly stuff after the play, that takes a toll,” he says. “People don’t want to be a part of that.” But he’s not all p.r.-approved smoothed edges. His quarantine pastimes included “a lot of virtual beer pong,” he says, laughing. “I picked up that hobby all over again.” Travis acknowledges, with arch seriousness, that the lack of in-person refereeing means the particulars of distance and elbow placement are beholden to an honor code. “It’s a gentleman’s game.”

Jason spent his offseason in Philadelphia, training at team headquarters, and with his wife, Kylie, caring for their 10-month-old daughter, Wyatt. He speaks of the difficulties 2020 has posed to each undertaking. The Kelces’ mother, Donna, had to stay home in Orlando during the spring due to COVID-19, and when she visited Philly in the early summer months with Travis, who arranged a private flight, the family did what everyone else did: stayed in, ordered takeout, reminisced about normalcy. (Ed, the Kelces’ father, lives in Philadelphia; the couple divorced in 2011 but remain friendly.) And while Jason’s status as an injured player allowed him access to the Eagles’ facilities—a silver lining to a recent spate of elbow, knee and foot issues—he missed the camaraderie and tempo of normal activities. “The building is completely empty,” he says. “You don’t get to interact with teammates, you don’t get to interact with coaches, you don’t have that.”

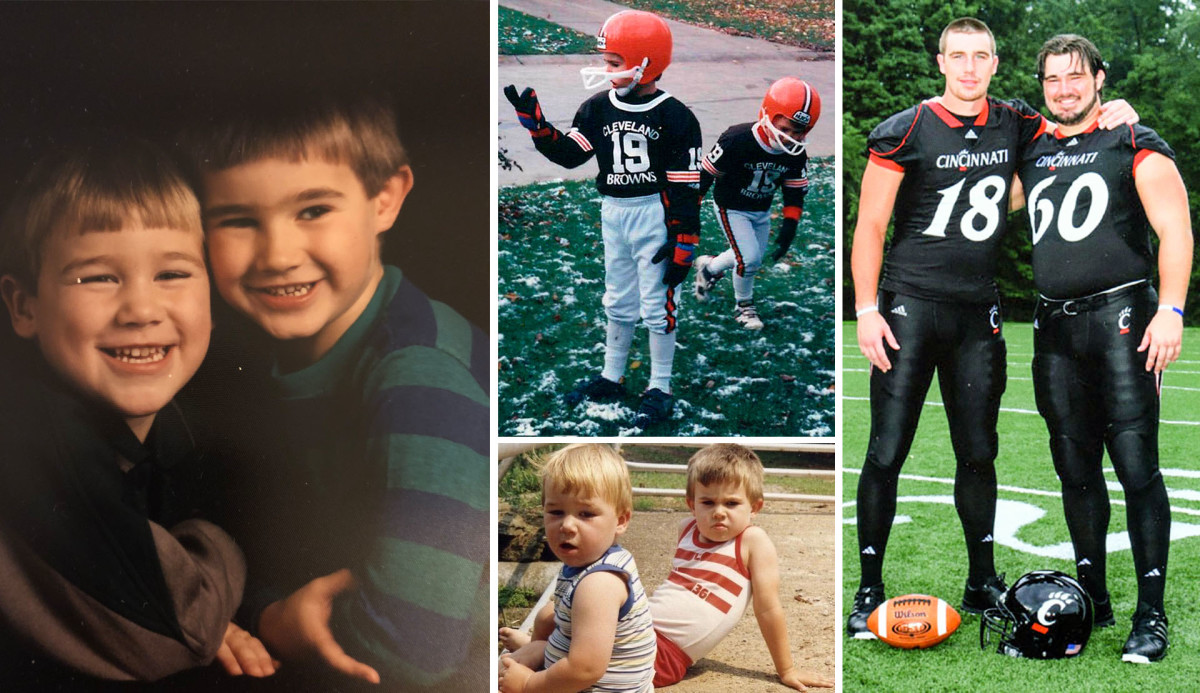

As kids growing up in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, where Ed sold steel and Donna worked in banking, the Kelce boys were constant raucous companions, both teammates and rivals. They smashed lacrosse balls against basement walls and hockey pucks into the garage door. When they weren’t destroying their home, Travis tailed Jason around the neighborhood, taking part in pickup football and basketball games against a brother two years older, many pounds heavier and disinclined to take it easy. “There were a lot of fights,” says Donna. “There were a lot of punches thrown. It all just stemmed from somebody being better than the other one, and the other one not being able to deal with it.”

At Cleveland Heights High, neither played the position he would eventually star in as a pro: Jason was a linebacker, Travis a quarterback. In the winters, Travis played basketball and Jason hockey. Ed claims both boys’ best sport was baseball. Asked for a comparison for Jason, he replies, “You heard of Thurman Munson?”

Jason walked on as a linebacker at Cincinnati, transitioned to O-lineman and earned a scholarship. Slotting in alongside future NFL blockers Jeff Likenbach and Trevor Canfield, he helped push the Bearcats to their first three double-digit-win seasons in school history. “He was a wonderful example of effort, intensity, and passion: for the game, for his teammates, for victory,” says Kerry Coombs, Cincinnati’s defensive backs coach at the time. “If you’re going across the street and getting in a fight, you’re taking Jason with you.” Travis, the more eye-poppingly athletic of the two, followed his brother to UC two seasons later as a wildcat quarterback and tight end.

In 2009, at the end of Travis’s redshirt freshman year, he failed a test for recreational drugs before the Sugar Bowl. When Butch Jones arrived to coach the team the following year, he dismissed Travis from the program, citing a need to overhaul the culture. His housing revoked, Travis had nowhere to live, so Jason brought him into a place he shared with teammates. Travis spent the 2010 season administering phone surveys, gauging public support for the Affordable Care Act. Donna took out loans to pay for his textbooks.

Coombs remembers Jason walking into a coaches’ meeting that season, tears in his eyes. He was there to stake his substantial reputation on getting his brother back in the fold, and he came armed with a straightforward argument. “Basically, it was, I’ve got this, and you’ve got to trust me on this,” Coombs says. “You’re talking about a man who had earned the right to give his word and have his word listened to.”

“I never really asked him how he got me back on the team,” Travis says. But he returned for his junior season in 2011 as a full-time tight end and made the dean’s list that fall—“which was unheard of,” according to Ed. In ’12, Travis broke out, catching 45 passes for 722 yards and eight touchdowns; the following spring, the Chiefs drafted him in the third round. “That was my brother just being a big brother,” Travis says, “looking out for me every step of the way and fighting for the success story.”

Jason deflects credit. “[Travis] wasn’t a bad kid,” he says of the Cincinnati dismissal. “I fully anticipated him being fine.” He sees Travis’s success not as evidence of his own mentorship but as a simple byproduct of talent—a reading that fits a general preference to talk football, not the other stuff. Both brothers brighten when asked about on-field specifics; both glow when asked about each other.

“Jason thinks like a defensive coordinator,” Travis says. “He was a linebacker, so when he made the transition to offense, he was a step ahead. He knows where guys have to fill the gaps. He understands how a defensive line moves, if the defense rotates this way, in the back end they have to do the opposite. . . . There’s certain things that register in his mind that I—I’m amazed, when I see on film.”

“I think skill-position players are better when they’re artistically inclined,” Jason says of Travis. He slips into a story from their childhood: Ed bought both boys the same Lego set, and where Jason followed the instructions to a T, Travis simply looked at the outside of the box and followed his intuition. “You have to know how to create within space, especially when you’re working by yourself. His ability to understand spacing, to have an instinct to know when to cut, when he feels somebody approaching him to make a spin move, to juke to get extra yards—that’s what I think really makes him special, besides the fact that he’s 6' 5" and an athletic freak.” Jason pauses, considering how to temper the string of compliments. “I would never call him a genius off the field, but he is a genius at knowing how to operate and how to use his physicality.”

Recent NFL history would likely look far different if not for the peculiarities of the Kelce football gene. The ascent of backup quarterback Nick Foles grabbed headlines after Super Bowl LII, but it was Jason’s brutal precision against the Patriots’ defensive scheme that kept Foles upright. He cleared space for 164 yards of rushing offense; he detected and blew up the Belichickian stunts that made up New England’s pass rush. A clip that circulated after the game showed Jason helping on a double team on the right side of the line and then, as if seeing through the back of his helmet, spotting a blitzing linebacker looping into the backfield. Jason peeled off, doubled back and picked him up at the last second; Foles was never touched.

Two years later Travis played a similarly crucial—if more telegenic—role for the Chiefs as they became the first team to roll off three consecutive double-digit playoff comebacks en route to a championship. In the AFC divisional round game against the Texans, which began with K.C.’s offense sputtering as Houston grabbed a 24–0 lead, he commandeered the middle of the field, hauling in 10 Mahomes passes for 134 yards and three scores while the Chiefs ripped off seven consecutive touchdown drives. Afterward, Travis offered a succinct explanation of how he helped engineer one of the biggest come-from-behind wins in postseason history: “When in doubt, make plays.”

* * *

Athleticism and strategic acuity—the ability to spot and then adjust to a blitzing linebacker, the awareness to time a break with a safety’s misplaced cleat—are of secondary importance to the Kelces. The point of football is one and the same as the means of succeeding at it: committing yourself completely, body and intellect and spirit, to a team. When he tries to define the Chiefs’ championship makeup, Travis loads clichéd sentiments with the force of true belief. “When everyone plays and has passion for each other, man, that’s when you really have a chance to be great as a team. Without it, I don’t know how football even works,” he says. “If you don’t care about the guy next to you, one, you’re a terrible teammate. Two, you’re never gonna win.”

Jason is a born field general. “He was just a nasty, dirty mother hover,” says Jeff Rotsky, who played against Jason in high school and later coached Travis. Rotsky describes a player who would light into his teammates at halftime but, during the game, avenge any after-the-whistle hits or blindside blocks on them in short order. “He controlled their team. He was the unequivocal leader.” Travis’s morale-building is founded on a contagious confidence—he celebrates his teammates’ touchdowns more exuberantly than his own, these days—and shot through with affection. “Travis thought he was never going to lose,” says Coombs. “He didn’t have to be breathing snot out of his nose like Jason, hollering and screaming.”

Over the course of their NFL careers, though, the brothers have borrowed from each other’s tendencies. “Jason has learned to have fun, and Travis has learned to be that consummate professional,” Rotsky says. “They’ve both rubbed off on each other in a really positive way.” The effect of Jason on Travis is more readily apparent; the younger brother’s unsportsmanlike conduct totals have dropped, he was voted a Chiefs captain for the past three postseasons and he can now credibly deliver speeches to young teammates on the importance of offseason training and extra reps. (“It’s technically quarantine, we’re not supposed to be here, we’re not supposed to be there,” he says, with a Jasonian skepticism of excuses. “You have to find a way to get the work in.”)

But the effect of Travis on his older brother has been no less substantial. “Sometimes it’s so easy for me to get caught up in my own head, selfishly looking at things from my own perspective, that I forget how important it is to uplift other people,” Jason says. “Not by these rah-rah speeches and not by getting in somebody’s face but just by being a genuinely happy, emotional guy.”

The cross-pollination of leadership styles has resulted in, among other things, the Speech. It is part of championship lore in Philadelphia, a stream-of-consciousness, expletive-laden, 5 1/2-minute ode to perceived inferiority and the transformative power of grit. Five days after the 2018 Super Bowl, when the championship celebration ended up on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jason strode to the podium dressed (in a nod to the city’s famed Mummers Parade) as a rhinestone leprechaun, a green and audaciously lapelled suit on his ample torso and a wrap on his head. He listed the cases against his teammates, and himself. “Stefen Wisniewski ain’t good enough, Jason Kelce’s too small, Lane Johnson can’t lay off the juice, Brandon Brooks has anxiety!” His voice cracked. “You know what I got to say to all those people that doubted us, to all those people who counted us out, and everybody who said that we couldn’t get it done?” He pointed into the thicket of increasingly giddy Eagles to his side. “What my man Jay Ajayi said: F--- you!”

The Kelces’ parents and former coaches—anyone who has been in a locker room with the brothers—know that version of Jason well, but they also know it rarely appears in public, and they credit his younger brother with loosening Jason up and teaching him the value of a good celebration. Travis is delighted that the world got a glimpse of Jason in full. “I’ve seen a speech like that hammered. I’ve seen a speech like that aggressive and angry,” he says. “And I’ve seen a very passionate, loving, big old bear that we know as Jason Kelce, like he was that day for Philly.”

* * *

The 21st-century NFL has produced two dominant traditions. The first is Bill Belichick’s, built on well-guarded institutional knowledge, unbending doctrine and a taste for subterfuge. The other is Andy Reid’s, which favors high experimentation and low 40 times. Reid picked Jason in the sixth round of 2011 and coached him for two seasons before Chip Kelly took over; four years later, Reid protégé Pederson picked up where his mentor had left off. In Reid’s first year in Kansas City, he selected Travis. On that draft day, Reid reportedly asked Travis to hand the phone over to Jason. “Is he gonna screw this up?” Reid asked. Jason told Reid what he told the staff at Cincinnati: “No, Coach, I got you.”

The Kelces are quick to defend each other’s skill sets—Jason maintains that Travis, never celebrated for his blocking, could be as effective as the 49ers’ George Kittle if required—but they admit that the Reid school fits their shared football sensibility perfectly. “What makes Belichick a great defensive coach is what makes Reid a great offensive coach,” Jason says. “The best coaches find a way to utilize guys’ skill sets and talents. I don’t think that I’m necessarily an unbelievable player for every offense, right, but I have a great skill set, and when [Reid and Pederson] utilize that, I can be a very successful player.”

Travis, who over his career has gone from K.C.’s primary receiving threat—in his second season he caught five touchdowns; the team’s wide receivers caught none—to one in a cadre of downfield targets, refers to Reid’s offense as a kind of football nirvana. “Every summer, I’ll just pop my head into Coach Reid’s office to say hello, and he’s got a four-inch stack of notecards,” Travis says. “He’s just licking his chops, like, I can’t wait to install these babies.” In the fourth quarter of a close game against the Lions last September, Travis caught a 12-yard pass over the middle and, as he was being tackled, lateraled the ball to running back LeSean McCoy, who scampered for an extra 20. It was the sort of risky play that coaches tend to reprimand, even when they work out, and Travis worried about Reid’s response. “After the game,” Travis says, “he just looked at me: ‘Imagine doing that the whole game.’ ”

In his retelling, there’s an echo of the dares the Kelce boys flung at each other growing up. One afternoon, Travis bet Jason that he couldn’t throw a football over their three-story home. Jason stationed himself in the front yard; Travis waited to receive in the back. The challenge ended in some stern parental words and a trip to the hardware store for a new pane of glass—how else?—but it also reinforced a sense of sport as possibility. Things can’t go right unless you’re willing to go all out. And when they go wrong, someone’s there to take the heat with you.

* * *

Football players tend toward low-grade superstition, and the demands of the sport encourage looking forward, not backward, all of which makes them hesitant to talk about their accomplishments. The tendency holds for Jason and Travis; neither is much interested in reminiscing over his own Super Bowl.

Both of them, though, will happily detail their memories of the other’s. When Damien Williams scored the Chiefs’ final touchdown in February, putting the game out of reach, Jason headed from his seat in the stands down to the field. “I was just running through the stadium, very emotional, crying,” he says. “Winning it yourself is a very self-gratifying thing—like, I’ve worked my entire life to do this—and that has its emotions in its own way, but seeing someone you love and care about accomplish their dreams is potentially more gratifying.”

Travis agrees. “The happiest I’ve ever been for him was seeing him win the Super Bowl and seeing how crazy he went on the field. A guy with so much passion for the people around him, the ultimate leader.” He pauses. “It always gets me a little emotional thinking about that.”

Donna watched the Eagles’ Super Bowl win from a suite with Travis. As the clock wound down, she wondered how her younger son would react, how much envy might cut the vicarious joy. “It was always a competition between the two of them, and that still has not gone away,” she says. Travis told her that he was glad Jason got one, but that he wanted the rest. Then the moment got quieter, the first blast of celebration giving way to the settling realization of what Jason had accomplished, and Travis said something else: “I hope my brother stays this happy for the rest of his life.”