What the Mahomes Contract Really Means

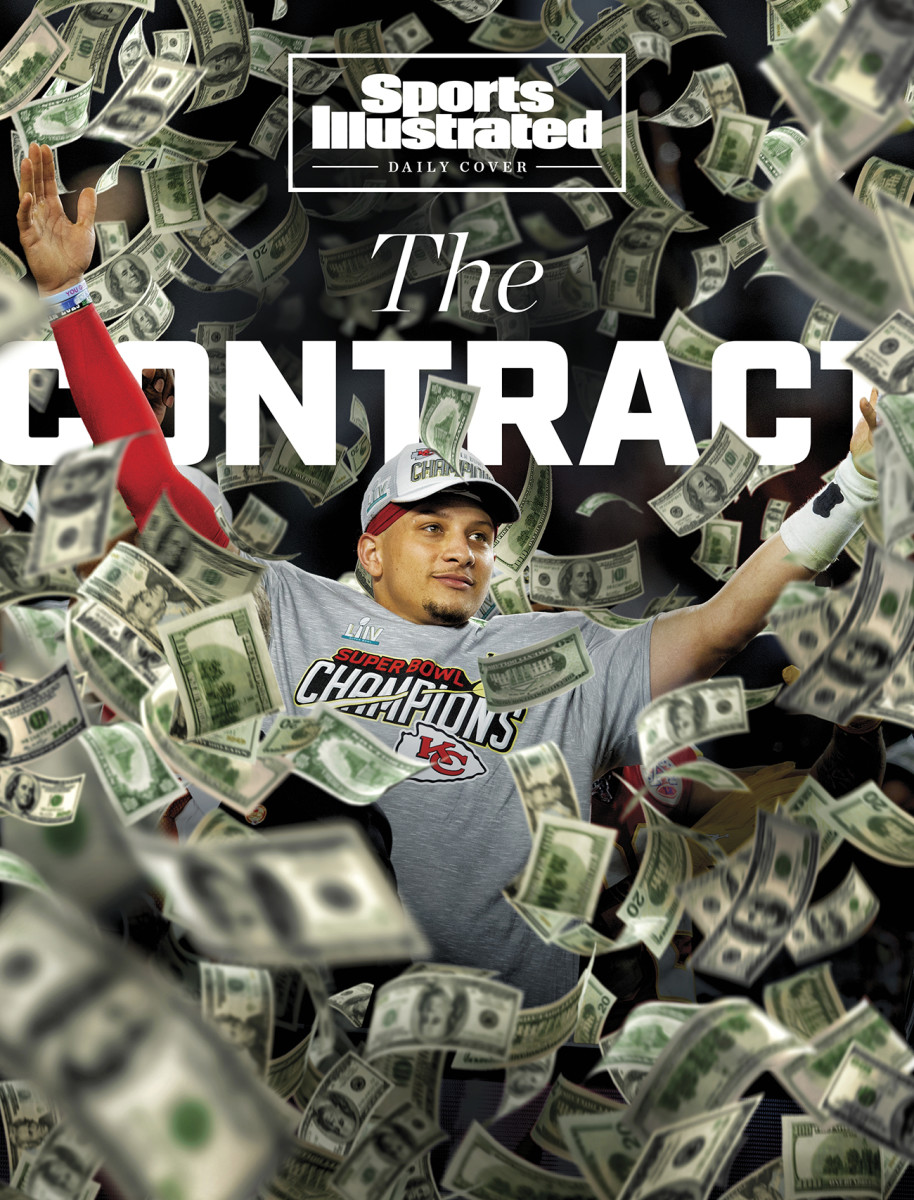

The Contract just sat there, on a table at Andy Reid’s house, near platters offering cold cuts, hummus dip and vegetable medleys. A bucket of Dom chilled on ice, next to the banner standing close by, the one emblazoned with Chiefs logos to properly announce The Contract to the world. In heft, The Contract resembled an old phone book, clocking in at more than 100 pages. And, as signing hour approached on an early-July afternoon, everyone in the inner circle of Patrick Mahomes looked both backward and forward, hoping to contain news of the historic extension for another few hours.

Then, as lawyers for the NFL Players Association scoured the final details in an agreement that had taken 18 months to complete, the story broke like a dam overwhelmed—and from the most unlikely insider, a beer manager/die-hard Chiefs supporter at a downtown Kansas City liquor store. Mahomes and his closest confidants—agents Chris Cabott and Leigh Steinberg; his father, mother, two siblings and girlfriend; plus top members of the Chiefs brass (minus Reid, who could not have any contact with his players)—could only laugh. They knew exactly what would happen next.

The Contract instantly became a historical sports document, its parameters criticized by other agents, praised by Mahomes and celebrated by the beer manager and others throughout Chiefs Kingdom. The Contract could* be worth half a billion dollars and should* tie Mahomes to KC for the rest of his career. And, in a broader sense, The Contract would also be shown to embody both how NFL deals differ from agreements in other sports, and how they rarely deliver exactly as laid out.

Mahomes scribbled his name onto the white pages, making the document legal, securing mind-boggling, generational wealth. The whole group posed for pictures, cracking open the bubbly as general manager Brett Veach toasted to a future of Super Bowl championships like the one they nabbed back in February. Cabott thanked his counterparts from the negotiating table. Social distancing measures were taken because of COVID-19. Someone even saved the pen that Mahomes used as a memento. The only thing missing was one of those giant game-show checks.

Finally, just as they had done after Mahomes agreed to his rookie contract in 2017, the quarterback, his agents and Veach looped signatures onto a Chiefs helmet. Almost three years to the day, exactly. As Cabott would note later, the people in the original pictures and the current ones were also exactly the same.

Patrick Mahomes, budding NFL icon, had made history once again. The headline: 10 years, $503 million, largest deal in the history of sports. The truth, while no less groundbreaking, is quite a bit more complicated.

* * *

Representatives for Mahomes first examined the basic parameters for an extension in January 2019. They wanted to lay out for the superstar what they considered the two most important factors in any deal: whether he would reset the quarterback market in a short-term sense or a long-term one, and how either option would work in tandem with the Chiefs’ salary-cap dynamics, both for overall philosophy and available cash.

In terms of fit, the answer could not have been simpler. Mahomes loved the small-town feel of Kansas City, how he could dine out uninhibited; he loved his owners, the Hunt family; his boss (Reid), his offensive coordinator (Eric Bieniemy) and his position coach (Mike Kafka). Steinberg’s relationship with the franchise dates all the way back to 1977, and he has represented some Kansas City legends, from the late Derrick Thomas to Christian Okoye to Tony Gonzalez to one Patrick Mahomes.

As the Super Bowl season unfolded, the quarterback’s reps continued to drill deeper on short- versus long-term options. A three- or four-year guaranteed deal held great appeal and fit with recent trends throughout sports. Foremost, it would allow the agents to renegotiate again while Mahomes remained in his prime and the salary cap continued to rise like an elevator that would never stop. But Cabott saw one prominent hang-up with a shorter agreement: Unlike in baseball and basketball, when an NFL star signs a deal, the team must immediately fund all of the guaranteed cash to the NFL, and he believed it would be more difficult to maximize the money for that reason. The agents looked into taking out an insurance policy to offset the unlikely but not impossible event that Mahomes wouldn’t be able to negotiate for a third time (like, if for any reason, he never played again). But none of the policies, combined with a shorter, all-guaranteed contract could net as much total as the longer-term options.

Steinberg had long sought out contract innovations. He helped Steve Young push cash to later years in one deal while accurately predicting that then President Ronald Reagan would drop tax rates. He helped create the concept of “voidable” years so that top players could reach free agency earlier if they hit basic incentives.

Now, Team Mahomes sought to find a permissible route around that cash-up-front rule. They settled on a clunky term: guarantee mechanisms. Both Cabott and Steinberg describe it as the latest innovation in the evolution of pro football contracts. The first five years—and roughly $140 million—of Mahomes’s deal are guaranteed against injury. But for each year that he remains on the Chiefs’ roster, significant, eight-figure chunks—at least $21.7 million (’21) and as much as $49.4 million (’27)—become guaranteed. There are buyout opportunities, but those very guarantees make releasing Mahomes in any one season prohibitively expensive, which to his reps means that Mahomes basically signed a guaranteed contract, without the Chiefs needing to lay out over $400 million up front. In the improbable event he is let go, he would then hit the open market.

Mahomes did not take the same route as Kirk Cousins, who played out two franchise-tag seasons with the football team in Washington, then signed for three years in Minnesota for $84 million guaranteed, then renegotiated this spring to add two seasons but help the Vikings increase their 2020 cap space. Mahomes chose the opposite path to the same place.

The structure, Cabott says, borrowed from basketball in the guarantee mechanisms and from baseball in the no-trade clause the Chiefs agreed to, making it unlike any agreement in NFL history. Mahomes came to like the longer, more creative option best. “This way,” Cabott says, “he reset the market at the position and for the sport and for all of sports.”

* * *

Given the remarkable nature of The Contract, the Mahomes deal includes a game of sorts. Call it Fun With Numbers. It’s like Mad Libs, except instead of “insert adverb” it’s “insert detail that supports your take.” The basics: Mahomes signed a 10-year extension, on top of the two years that remained on his rookie deal. The extension is worth $450 million, plus incentives, and could tether Mahomes to K.C. through at least 2031, when he’ll turn 36. According to ESPN’s stats crew, Mahomes will earn $1.60 a second, $96 a minute and $137,808 a day for the duration of the agreement, which, were it a country, would compare favorably to the GDP of Tonga, the 196th richest nation in the world.

The baseline: Mahomes will bank some 19,000 times more than the fee Lamar Hunt paid ($25,000) to create the Chiefs franchise in 1960 because he is Patrick Mahomes. Because he is an NFL and Super Bowl MVP; young, charismatic, healthy and, despite not yet being in his prime, the biggest star of the most popular league in America. He’s worth multiples of every dollar anyone could pay.

And yet, examining any NFL contract, let alone one of the longest and largest ever, is like exploring numbers through fun-house mirrors after partaking in cannabis. Nothing is exactly as it appears, beyond the guaranteed cash. Here, there’s the big number—$502.6 million—that Mahomes could collect over the next 12 years. But to collect in full, he’d need to reach the Super Bowl and win league MVP every season.

There are averages involved in assessing the agreement—like the $10 million-plus bump over Russell Wilson’s previous average-per-year record—a nice break for the team in the first two seasons and essentially two deals merged into one contract, with the second half of the extension averaging over $11 million more than the first. Studying these numbers can make for a dense, dizzying exercise, like reading an NFL math class textbook cover to cover, hence the number of pages. But the most relevant notions are 1) Mahomes will become really, really rich, 2) the chance that he realizes max value is close to zero, 3) the chance he plays out the entire duration is lower than 100%, and 4) the contract is likely to change to suit the Chiefs’ needs in any given year.

Whatever numbers are chosen, of course, represent the kind of grand sum that a bank would envy, let alone the guy hawking beer in the nosebleeds at the stadium where Mahomes stars. No one is saying he’ll ever want for cash, or was ripped off by the Chiefs. But the deal is also instructive, especially in its potentially confusing impact on the market for quarterbacks like Dak Prescott and Lamar Jackson, or the recently signed Deshaun Watson (four years, $156 million and $73.7 million guaranteed at signing).

In fact, as wild as it might seem, many see The Contract as a team-friendly bargain given the inevitable salary cap increases between now and 2031, and the leverage that Mahomes “lost” by not being able to renegotiate for up to three presidential terms. “I thought it was a great deal for the Chiefs,” says Jason Fitzgerald, the contract expert at overthecap.com. “I was shocked. It’s unlike any contract in the last 15 years.”

Unsurprisingly, the deal’s most fervent critics are agents who do not represent Mahomes, and they lob their length-and-leverage criticisms anonymously. They point out that only 15 other active NFL players have signed six-year contracts and none for more than eight seasons. That’s because, like with the NBA, the trend toward shorter contracts means they can renegotiate more often. “If he signed for one-trillion for one year, we still would have heard all that,” Steinberg quips.

Given those factors, Mahomes could be leaving money on the table, even if his table is filled with bundles of cash stacked to the ceiling, the leftovers piling up in adjacent rooms. Cabott disagrees. He argues that they did realize full value. Either way, the pertinent questions are why? And for what?

* * *

Back around the turn of the century, several high-profile QBs inked deals similar (relatively speaking) to the one that Mahomes just signed. In 2001, Brett Favre agreed to a “lifetime” pact with the Packers for $101.5 million, followed by Drew Bledsoe’s $103-million deal. Donovan McNabb went for $115 million in ‘02, over 12 years, the longest-ever contract at the time. Then Michael Vick ($130 million) and Daunte Culpepper ($102 million) joined the nine-figure-check club with contracts that ran long in years. “I thought those days were pretty much done,” Fitzgerald says.

To Steinberg, the length of those agreements highlighted how pro football had evolved from a run-the-ball-and-play-great-defense league into a passing juggernaut. Only the rare team could win Super Bowls without a truly elite quarterback. Which is why, combined with billions in television revenue, previous record-setting deals he had negotiated—around $640,000 for Steve Bartkowski from the Falcons in 1975 and $45 million for Steve Young from the 49ers in 1997—pale in comparison with Mahomes’s now fully stocked bank vault.

Steinberg also came to realize that skyrocketing quarterback salaries could come at a substantial price for teams that desired to maximize talent around their salary-cap-eating stars. Hence the rash of longer-term, more flexible agreements. Mahomes settled on similar reasoning, choosing to bake both long-term stability for himself and cap-flexibility for his team into The Contract. “We achieved all our goals for a mega-deal and gave him the best chance to chase a dynasty,” Cabott says.

McNabb used that same logic, while playing for the same coach, almost two decades ago. The rationality still resonates, soundly, in that players of their stature care about both money and winning, and taking the absolute most means taking from someone else who might help them win. In the eight seasons that McNabb played for Reid under the long-term deal, the Eagles made the playoffs six times, advancing to four conference title games and one Super Bowl, giving themselves numerous chances to triumph, a best-case scenario in a league with vast parity.

Because those contracts are long and can be adjusted, if Kansas City is strapped for cash, it can rework the deal in any one season to funnel money earmarked for Mahomes to key teammates or prized free agents. If the Chiefs are flush with dollars in another campaign, they could dump more into Mahomes’s coffers with similar but opposite tweaks, an exercise in balancing two enormous scales. Where pro baseball teams can spend over luxury tax thresholds to hoard talent, NFL franchises are capped in total dollars ($198.2 million in 2020), making this exact kind of flexibility more important for any team to consistently contend. It’s not like Mahomes needs every single dollar, anyway. McNabb, asked whether he saved any mementos from his famous signing, laughs and says, “a whole lot of money, more or less.”

The Contract allows Mahomes to assist Veach with more than his arm. Just like Tom Brady, who in 20 seasons with the Patriots often took below-market deals to help New England reach Super Bowl after Super Bowl but still ranked among the most handsomely compensated players in the league. It helped, of course, that Brady’s wife commanded higher earnings as a supermodel than he ever could in football. Still, the Mahomes extension is as friendly, if not more so, than anything Brady signed, and that’s because of the total years. Brady never agreed to more than six seasons in one deal ('05), and even then, he renegotiated after three years.

Already, Mahomes helped Veach reach extensions with two Pro Bowlers—defensive tackle Chris Jones and tight end Travis Kelce. If the Chiefs can lock in safety Tyrann Mathieu (up after ’21) and speedster Tyreek Hill (’22), they will have all their cornerstones signed for an extended playoff run. Without The Contract and its malleable nature, that would be impossible.

When Mahomes completed his agreement, McNabb sent him a text message. He congratulated the young star, but also implored Mahomes to not play with any added pressure in the years ahead. McNabb had found that living up to The Contract becomes its own sort of beast. “At the time you get paid, you feel like you have to be Superman,” McNabb says. “And we didn’t even have social media. He’s going to hear rumblings. He’ll be an extension of the GM, and some guys who don’t get contracts are going to try to blame Patrick, say he didn’t stick up for them. There will be people in the locker room who will be pissed off he gets to do whatever he wants.”

The possibility of change—in locker-room dynamics, with The Contract’s parameters—will linger over the agreement. All the nine-figure-check-club quarterbacks learned that a decade is a long time, a lifetime, in the NFL—a lesson they absorbed through personal experience.

* * *

Anyone assuming that Mahomes will enjoy a perfect and perfectly long career in Kansas City has ignored or missed the shifting, uneven history of most long NFL contracts. Things happen in a league with a 100% injury rate; bad things, usually. Injuries. Roster overhauls. New regimes. Tough years. Great backups.

Of the five quarterbacks who, before Mahomes, signed those game-show-check deals, none finished their respective careers with their original team. Favre volleyed between retirements and comebacks. McNabb, Vick and Culpepper each played for three or more franchises. And then there’s Bledsoe, whose story is basically folklore.

Unlike Mahomes’s, Bledsoe’s generational contract marked his third deal. Negotiations began well before the ’01 campaign, when Bledsoe ranked among the biggest stars in the NFL; some dude named Brady was his little-known backup. At one point, Bledsoe’s agent, David Dunn, had reached an impasse with New England, and Bledsoe received a surprise phone call at his house in Montana where only a handful of people knew the number. It was Robert Kraft.

The Patriots owner laid out the gap that remained and asked Bledsoe if he would sign if the team went up to a certain number. Bledsoe cannot remember the specifics, but he did sign, with an admonishment from Dunn that the QB had cost them a few million. Unfazed and still rich, Bledsoe flew to New England in a snowstorm to deploy signature to contract.

In those days, NFL teams guaranteed far less in contracts than they do even now. Bledsoe’s deal, for instance, contained only $6 million guaranteed against injury (compared with $140 million for Mahomes). Either way, both highlight just how much funny money is included in NFL agreements, where total years and compensation are more like ideal suggestions than concrete terms. Bledsoe, of course, was injured six months after signing, and his replacement went on to lead the Patriots to the Super Bowl title that season—and then five more after that.

Bledsoe and his nine-figure deal became expendable. He learned then what NFL contract history has long demonstrated: Whatever loyalty a player shows or whatever length of time or total dollars he agrees to, the numbers that get splashed in headlines are misleading, if not downright inflated, more often than not. Bledsoe was traded to Buffalo, and renegotiated in '04, was released in '05 and signed a completely different agreement within hours with the Cowboys. The percentage Bledsoe actually received on his $103 million agreement clocks in at 21.3%—and a significant portion of that came from his $8 million signing bonus.

* * *

Shortly after Mahomes signed, networks and reporters began to describe The Contract as the largest deal in sports history, an NFL first, the amount surpassing what Mike Trout agreed to with the Angels in 2019: an eye-popping 12-year, $426.5 million extension. But such notions make prominent baseball negotiators wince, since Trout, as many note, is better positioned to collect on his sum total.

There are similarities to both deals beyond the headlines. Like Mahomes with Steinberg, Trout signed with a smaller agency and a long-established veteran agent in Craig Landis, his father’s former teammate. Trout, like Mahomes, elected to stay with the team that drafted him. Like Mahomes, his deal includes perks and restrictions. Both players cannot be traded without their consent. Trout receives a hotel suite on the road and a stadium suite for 20 home games. Like Mahomes, he cannot play basketball, or ride jet skis, or do anything that might be considered dangerous. For instance, Trout also can’t serve as a pit crew member, or do something called sky surf, or try any sport that involves using a firearm.

For all they hold in common, though, there are also important differences in the agreements. The biggest: guaranteed dollars. Were Mahomes to suffer a career-ending injury tomorrow, he’d make $140 million; Trout, in the same scenario, would collect his entire total, a difference in the neighborhood of $300 million. All the outs and “guarantee mechanisms” that stretched the Mahomes agreement to more than 100 pages aren’t included in Trout’s contract, which runs only 12, because it’s not complicated or deceptive in nature the way that all NFL deals, even the groundbreaking ones, can be.

For all the celebrated contracts signed in NFL history, retired Giants quarterback Eli Manning has banked the most cash, or $252.3 million over 16 seasons. Meanwhile, five baseball and five basketball pros have exceeded Eli’s sum, with more on the way as stars in those sports collect on money that has already been guaranteed. Mahomes, meanwhile, is at this point guaranteed less than struggling Orioles slugger Chris Davis ($161 million), which says more about NFL contracts than his specific NFL contract. Perhaps that’s why many contract experts believe the first athlete to sign for over a billion dollars will come from baseball, where there’s a luxury tax rather than a firm salary cap, allowing for blank-check choices among billionaires who desperately want to win. As likely: an NFL player inks a $1,000,000,000* deal, with a fraction of that total truly guaranteed.

* * *

The Contract will now join other famous deals in sports history, like the agreements for McNabb, Bledsoe and Trout. Along with, of course, the one that lawyer-agent Dennis Gilbert created for slugger Bobby Bonilla that binds the Mets to pay him $1.19 million annually on July 1 for 25 years, through 2035. Talk about long-term; Bonilla will turn 72 the same year his payments end. His agreement highlights the extended interest in the most famous contracts in sports history, along with the interconnectedness of that world. For instance, Gilbert has long known and advised Steinberg, and one of Bonilla’s teammates in Queens was Pat Mahomes Sr., father of the all-galaxy quarterback.

When Gilbert created the atypical structure, he says he cared little about how other agents viewed the deal, which was criticized like The Contract. But Gilbert had put together more than a thousand agreements, and he believed that long-term stability mattered, that too many players went broke when their careers ended. “When the money is there, you go for it,” he says, and he went for it, just spreading out the total so that Bonilla would be set for his years between when he retired and when his pension started to kick in. The deal continues to look more prescient over time, which taught the lawyer an important lesson. “Look, just because a contract is different,” he says, “doesn’t mean it’s worse.”

The stability sentiment, while especially prudent from any negotiator’s perspective, does ignore the fairest gripe over Mahomes’s pact: its impact on the market. The length of the contract could influence star quarterbacks, especially those approaching free agency, to land deals that run shorter in length. Dak Prescott, for instance, didn’t want the fifth year the Cowboys insisted on this summer, resulting in the sides failing to reach a long-term deal. Watson, meanwhile, landed the kind of blockbuster agreement that would have reset the market had Mahomes not extended with the Chiefs first. For that reason, many see The Contract as an outlier, rather than the start of a new, longer trend—another notion countered by Cabott, who says one NFL GM already told him “you really screwed me up here” in terms of the blueprint that the Mahomes agreement provided.

Prescott, like Watson, could sign an extension for a higher yearly average and shorter duration. He could mimic, say, LeBron James, who landed a series of mini (in time) and mega (in money) NBA deals, which helped him dictate decisions on coaches and teammates, because some of his leverage derived from the constant threat that he could leave. But what of the players with less leverage? “I’m happy for Patrick in that the numbers are more like what you’re seeing in other sports,” McNabb says. “It’s just the years in it [that’s an issue]. It’s like when Brady messed up the market for a lot of us. We had to explain to our organizations, our GMs, that his [deal] was a bargain deal.”

All of which leads to another, equally fair question: Should Mahomes really care about the market, over himself or his team?

* * *

As for the beer manager who broke the Contract news, Katie Camlin meets all the usual requirements for membership in good standing with Chiefs Kingdom. She keeps a favorite photo of herself as a toddler, wearing a KC cheerleader uniform. She had banked resolve through all the mistakes, missed field goals and unfortunate bounces that made each playoff loss more agonizing. She can cite favorite players who weren’t superstars, like Daniel Sorensen, the safety she affectionately calls Dirty Dan. And she gushed over Mahomes way back during the ’17 preseason, long before he became the team’s starter, let alone the face of the NFL.

She even has a special fork that her boyfriend held aloft during Super Bowl LIV last February, summoning good karma. Even after Mahomes secured a comeback triumph and the Chiefs snagged the franchise’s first championship in half a century, Camlin refused to wash the utensil, lest it lose its considerable powers.

She topped that this summer, tweeting her way into an unlikely position as a footnote in Chiefs and NFL history. It was a sequence of events almost as improbable as the perennially hard-luck franchise in barbecue country becoming an NFL dynasty. Camlin’s path to internet fame began when she was furloughed by a brewing company after COVID-19 began to spread. To pay her bills, she took a job at that liquor store downtown. And, on one otherwise-regular afternoon shift in July, the beer manager at Plaza Liquor arrived just in time to hear some incredible news: Her colleague had just sold six bottles of Dom Perignon to a Chiefs employee who let slip that he required the bubbly for a major celebration.

Now, Camlin realizes all that’s in play—the history, the magnitude, how this one very big and very long agreement will impact the future of the NFL. “I do have this fantasy in my head where in non-COVID times they bring Patrick into the store and we have a hug,” she says. “It’s borderline emotional to think about. He’s amazing. The contract is amazing. Who cares about [the criticism]? He’s ours.”

This is the life that The Contract has been given. It will be scrutinized and analyzed, celebrated and picked over, for years to come. The takeaways might change, as could the parameters. But not the significance. Pick away, critics, Mahomes and his reps and his fans say. Half a billion is half a billion, and this agreement, while not exactly as it seems on paper, will find its place in the evolution of NFL deals.