Man Caves and Football Wives. Black Hats and Creepie-Peepies

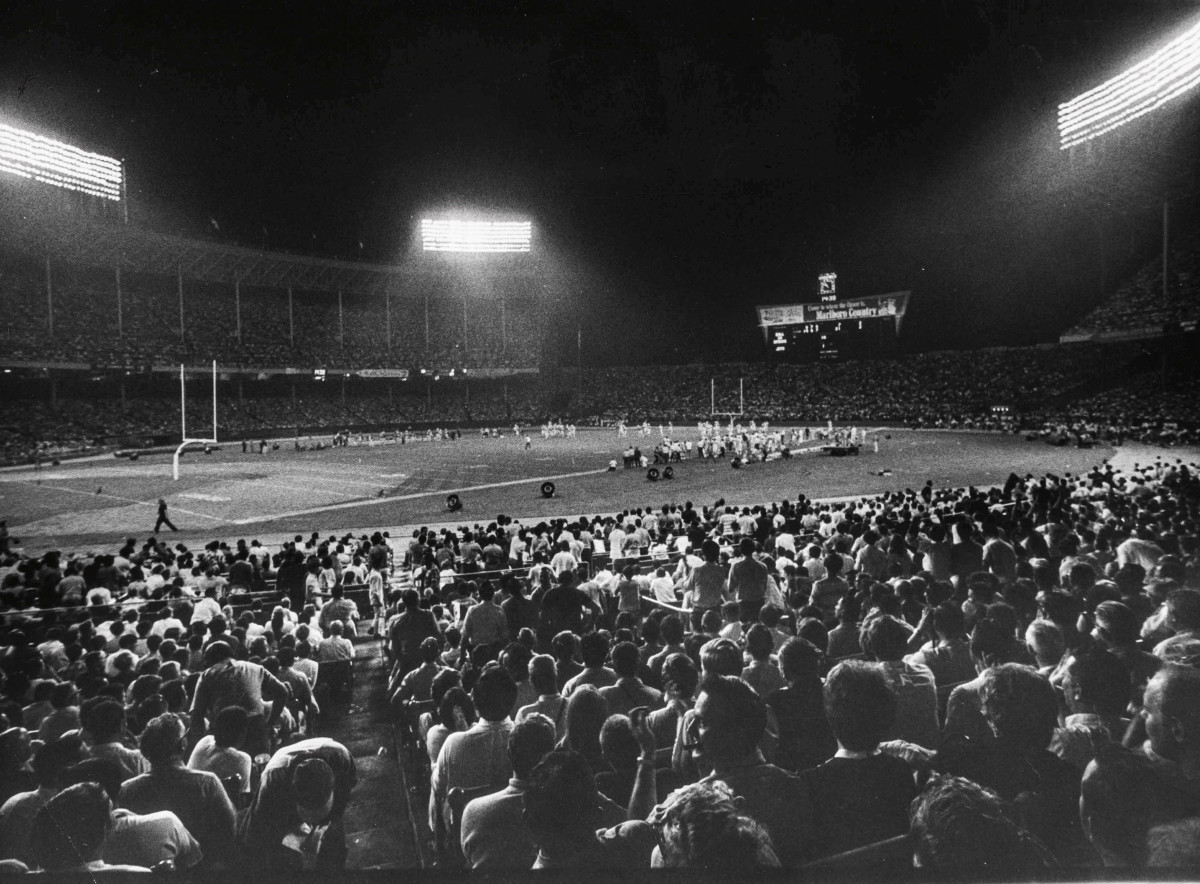

When the Steelers and the Giants take the field Monday, they’ll be following a trail blazed 50 years ago on an epic night in Cleveland, when the Browns and the Jets faced off in the premiere of Monday Night Football. That game, won 31–21 by Cleveland, was memorable to the 85,703 fans in attendance (and presumably the 2,000 rowdies who were turned away outside), the television audience that watched the technologically unprecedented broadcast in their dens and the players who took part—everyone involved, really, except the man who scored the first points in Monday Night Football history.

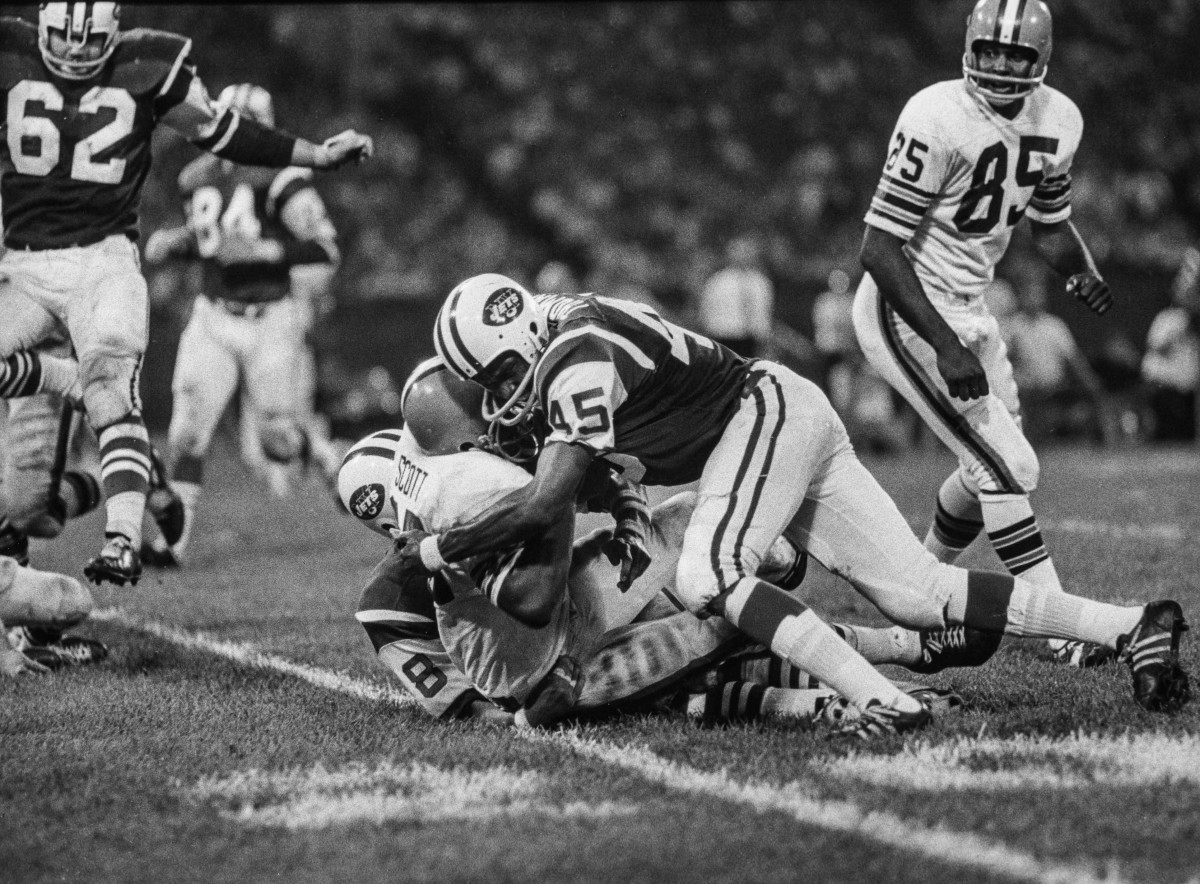

“I don’t remember nothin’,” says former Browns receiver Gary Collins, who at 80 has a wonderful memory with regards to just about everything else outside the events of Sept. 21, 1970. “I got knocked out in the third quarter.”

Indeed, Collins’s KO was just as significant as his TD. As he lay on the field at Cleveland Municipal Stadium after absorbing a knee to the back of the head while diving for a quick in-route pass (he held onto the ball), ABC’s cameras zoomed in on the Browns trainers waving smelling salts above his nose.

It was the kind of thing a viewer just didn’t expect to see in those days, when one of the (mostly) unwritten tenets of broadcasting the NFL was to shield the viewer from anything that might portray the game in a negative light. Four years earlier, the man who would procure the initial rights to Monday Night Football, ABC Sports president Roone Arledge, contributed a guest column for Sports Illustrated. “There’s no sense unduly emphasizing bloodshed, but guys do get hurt in football, and to pretend otherwise is simply childish,” he wrote. “I’ve seen an ambulance come out on the field and the announcer claim there’s a lull in the play.”

That’s not to say that ABC’s broadcast dwelled on the fate of the unconscious Collins in an unseemly fashion. Howard Cosell, already the most polarizing prognosticator in the business, was busy rattling off facts about the injured player in his grating, staccato manner: “He’s a smart, smart receiver. He doesn’t have the speed that he had in ’64, when he was Most Valuable Player in the title game, won by the Cleveland Browns …”

Next to Cosell in the three-man booth, Don Meredith, making his broadcasting debut, then broke down the juke that Collins had used to get open, which was being shown in great detail thanks to the technological novelty that was the isolated, slow-motion camera shot.

As a rejuvenated Collins jogged toward the sidelines, one thing was clear: For the NFL, this was—figuratively as much as literally—a new day.

***

Right around the time Collins was being administered his smelling salts on ABC, over on NBC The Tonight Show was in its monologue. Dean Martin was the guest host because Johnny Carson was on vacation, which was somewhat ironic, because without Carson, Monday Night Football—and by extension, NFL coverage as we know it—might look radically different.

Before 1970, ABC was the lone television network without a pro football deal, in keeping with its long-held (and well-deserved) reputation as a third-rate operation. Things gradually began to change for ABC’s sports division in 1960, when the network used a bit of cloak-and-dagger trickery to acquire the rights to NCAA football games. Bids for those broadcasts had been due at noon on March 14 in the NCAA suite at the Manhattan Hotel. Among the potential bidders: CBS had the NFL and wasn’t interested; NBC was the incumbent rights holder and the overwhelming favorite to remain as such. And ABC? It wanted in, and it had a plan. It knew that NBC’s director, Tom Gallery, liked to carry multiple bid envelopes on these occasions. If Gallery saw the competition dropping off a bid, he’d submit his high offer; but if no one else showed up, he’d go with the envelope containing the low one.

Ed Scherick, the head of ABC Sports, had convinced the network to put up a max of $6.2 million. That would likely be enough to top NBC’s low bid, but probably not its ceiling. And Scherick knew that if he or his deputy, Tom Moore, were spotted anywhere near the Manhattan Hotel, Gallery would go big. So Scherick found ABC’s plainest-looking employee—his name was, naturally, Stanton Frankle—and gave him the envelope. “We knew if anyone could melt into wallpaper, Stan was the man,” Scherick told SI in 1970. When Frankle left the ABC office at 11:45 with his envelope, “we shook hands. We were very emotional about the whole thing—as if Stan were Sergeant York about to infiltrate the enemy lines.”

Another car containing a second nondescript staffer followed with harsh instructions from Scherick: If you see Stanton hit by a cab or run over by a bus or knocked down by a bicycle or involved in an accident of any kind, let him lie. Do not touch him. Do not stop. Do not even slow down. Go to the Manhattan Hotel and do the deed.

Frankle, in the end, made it unscathed, and he lingered near the back of the room until NCAA officials announced that bids were due. Gallery looked around and, sensing that the coast was clear—no Scherick; no Moore—dropped off his envelope, presumably containing the low bid. Then Frankle came forward and handed over his envelope, like a trump card. “That was the beginning of the big sports breakthrough for ABC,” said Moore.

Now that he had the network’s first big rights deal, Scherick needed someone to run the broadcasts, so he hired a young producer away from a competitor. Arledge had felt trapped at NBC. He’d won an Emmy producing Hi, Mom!, featuring Shari Lewis and her sock puppet, Lamb Chop. Seeking bigger things, he pitched a highbrow anthology series called Masterpiece, which would feature deep dives on things like Michelangelo’s battles with the pope and the creation of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony. That one was shot down, as was another idea he’d called For Men Only, a lifestyle show featuring jazz performances and models in swimsuits announcing upcoming features. NBC declared it “a little ahead of the awareness line.”

Frustrated, Arledge began talking to Scherick, and before long he took a job at ABC, which, as Arledge wrote in his autobiography, Roone, was then “a place you get out of, not go to work for.” Scherick assigned his new charge to write a memo about how the network should cover college football. Arledge gave him a treatise on how their goal should be not to take the game to the viewer, but to take the viewer to the game. “We must gain and hold the interest of women and others who are not fantastic followers of the sport we happen to be televising.” He wrote of additional cameras mounted on Jeeps: “We will use a ‘creepie-peepie’ camera to get the impact shots we cannot get from a fixed camera.” (Hence, a dazed Gary Collins being plied with smelling salts.)

The memo went on: “In short—WE ARE GOING TO ADD SHOW BUSINESS TO SPORTS. ... We have a supply of human drama that would make the producer of a dramatic show drool. All we have to do is find and insert it in our game coverage at the proper moment. And this we will do!”

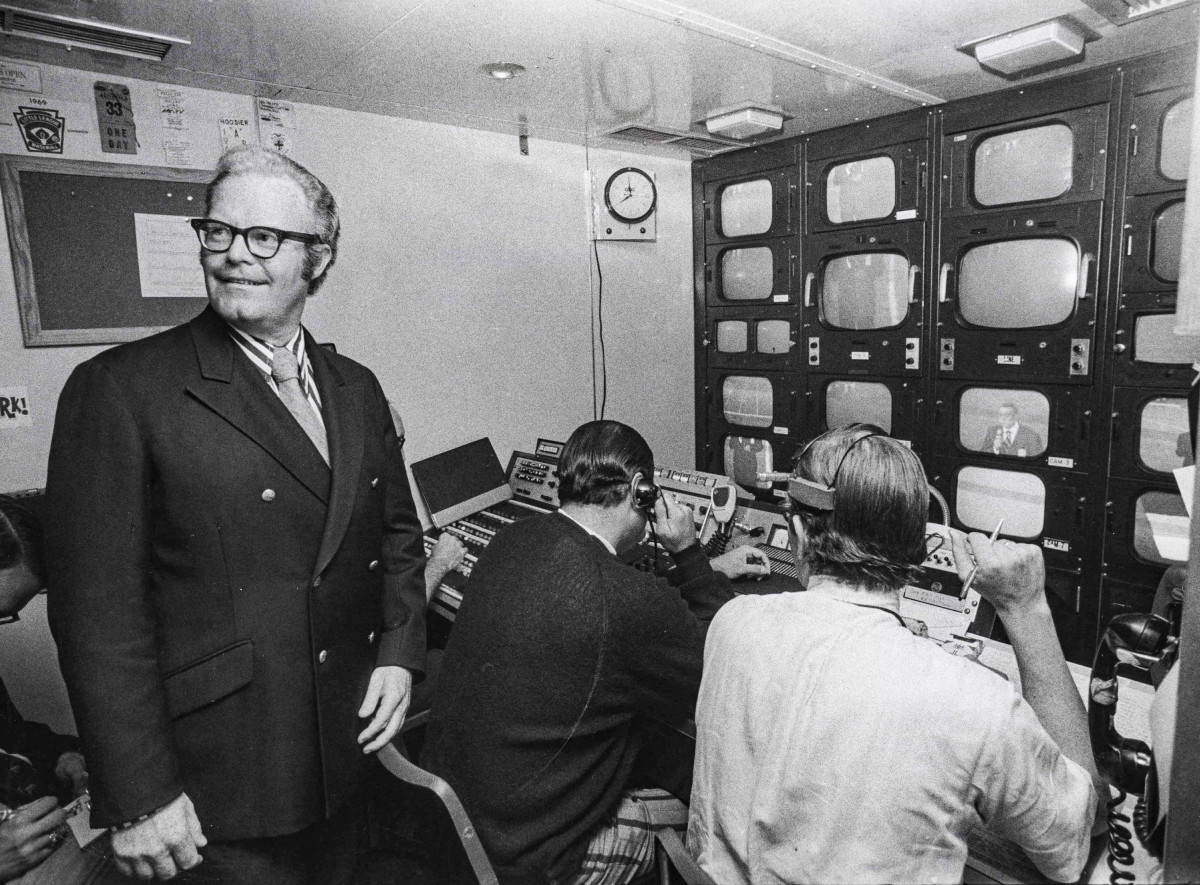

Throughout the 1960s, ABC went on collecting the rights to sporting events. And not just big ones, but also obscure ones, which became the basis for Wide World of Sports. (Arledge, the story goes, scribbled the catch phrase “The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat” on a cocktail napkin, the same medium on which he also supposedly helped draw up plans for slow-motion replays. Lots of cocktails in those days.)

As sports became an increasingly significant part of ABC’s overall programming strategy, Arledge quickly ascended the corporate ladder, becoming president of the network’s sports division in 1968. Two years earlier (as VP) he’d written his piece for SI about the state of sports broadcasting, and it echoed the themes of his college football memo: “When I got into it in 1960, televising sports amounted to going out on the road, opening three or four cameras and trying not to blow any plays. They were barely documenting the game, but just the marvel of seeing a picture was enough to keep the people glued to their sets. What we set out to do was to get the audience involved emotionally.”

Arledge looked at the major sports. Baseball was too slow, hockey too cluttered. Football, though … “Football and television have been ideal partners. They have a great affinity. The shape of the field corresponds to that of the screen. The action, although spread out, starts in a predictable portion of the field. It is a game in which action focuses on individuals.”

The problem was, Arledge was being shut out of football at its highest level. He wanted NFL action on ABC, badly. He had believed he pulled off a coup in 1964 when he found a loophole he thought would allow him to broadcast a doubleheader each weekend. This, he predicted, would give him the edge over his competitors in a closed-bidding process. First, though, an ABC lawyer called the NFL to verify that they were reading the bid document correctly. When CBS submitted an offer with a similar doubleheader plan, effectively sealing the deal, Arledge was convinced that commissioner Pete Rozelle had played favorites and tipped off CBS.

Unbowed, Arledge began what he called a “long-term campaign of cultivating Mr. Rozelle.” In his autobiography, Arledge takes a fair amount of credit for the Monday-night idea. In reality, though, Rozelle was the driving force. He knew that games on a third network would get the league another fat check every year. The NFL had tested out a few Monday games in the 1960s, but they were one-offs, and they were treated as such by CBS, which broadcast just four of the five. (The fifth was unaired nationally.) But fans showed up—in one of those Monday games, in 1964, Detroit drew the biggest crowd in its history—leading Rozelle to push forward.

Finally, over cocktails—lunch at Toots Shor’s, dinner at 21—Arledge and Rozelle settled on $25.2 million over three years for the Monday-night rights. (Howard Hughes tried, too, to insert himself, bidding on the rights for his upstart sports network, but that failed.) Arledge was elated … until Rozelle dropped a bombshell. He felt he owed it to CBS and NBC to give them the chance to match this proposed deal.

CBS, at that time, had a powerhouse Monday-night lineup, anchored by the Andy Griffith Show spinoff Mayberry, R.F.D., followed by The Doris Day Show and The Carol Burnett Show. NBC had only a movie at 9 p.m.—a prime-time game would have been an upgrade, for sure. But the problem wasn’t prime time. It was late night, where Carson was the unquestioned king. Asking him to start his show well after midnight once a week to accommodate football was a nonstarter. According to Jeff Davis’s book Rozelle, the comic great threatened to quit. According to Arledge’s book, NBC was too afraid to even ask.

Rozelle called Arledge: “I guess you owe a thank-you note to Johnny Carson. It’s your program.”

***

With the deal done, Arledge set out to assemble his broadcast crew. He insisted as part of the agreement that the league would not, as was the custom of the day, have right of refusal over the announcers. Free to pick anyone, he picked someone much of the country hated.

Howard Cosell was a very smart man—Phi Beta Kappa; editor of the NYU Law Review—and he liked to let people know that. He was also remarkably progressive in an arena that wasn’t. His association with Muhammad Ali (at a time when many broadcasters still insisted on calling him Cassius Clay) and his defense of John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics had led to many a letter landing on Arledge’s desk attacking the Jewish sportscaster’s religion and his views on race.

Arledge had plucked Cosell off the scrap heap after taking over at ABC. Cosell had done some work for the network in the 1950s, but mostly he toiled locally in New York because he was effectively blackballed at the national level. “A lot of it was anti-Semitism,” Arledge told Playboy in ’76. “But many other people just hated his guts on general principles.”

As he became the most famous broadcaster in the country, Cosell spoke his mind at every step, and that bluntness was what Arledge wanted. “I hired Howard to let people know I’m tired of football being treated like a religion,” Arledge told SI in 1971. “The games aren’t played at Westminster Abbey. It’s just a bunch of guys hitting each other.”

Cosell certainly had no problem filling the role of the beacon of truth. “TV announcing must change,” he said in July 1970, shortly after getting the MNF job. “People will no longer buy the shilling for ball clubs that takes place today. A new announcing approach must be formulated. In fact, I predict in the future you’ll need tougher Howard Cosells in broadcasting.”

For his MNF team, Arledge also wanted Frank Gifford (a P.J. Clarke’s drinking buddy), but he couldn’t persuade the former Giants running back to break his broadcasting contract with CBS. Giff had a suggestion, though: another former player, Don Meredith, who had abruptly retired as the Cowboys’ quarterback following the 1968 season.

Meredith lived 100 miles east of Dallas, in Mount Vernon, where he owned a mansion with a fountain that shot four colors of water, a stocked semiprivate lake and a pet coyote named Lisa. He had always been impulsive. Upon turning 30, Meredith found himself feeling blue. “When some people are depressed they go out and drink a lot or eat a lot,” he said in 1968. “When I’m depressed I buy something. So I bought the house, because your 30th birthday can get you down. I might have overdone it.” Less than a year later, he walked away from a team that had just gone 12–2. “I don’t want to play with the mental attitude I have,” he explained. “It’s like playing a round of golf and not taking all your clubs. I don’t want to play with half a bat.”

It was just this kind of down-home wisdom that Arledge wanted Meredith to impart on a nation of football fans. Dandy Don had always been a performer. At Mount Vernon High, he not only starred for the football team and the Future Farmers of America state championship shrub-judging squad, but he also took the stage in one-act plays. As a Cowboy, he released a song called “Them That Ain’t Got It Cain’t Lose,” and he’d been offered the lead in two different TV series.

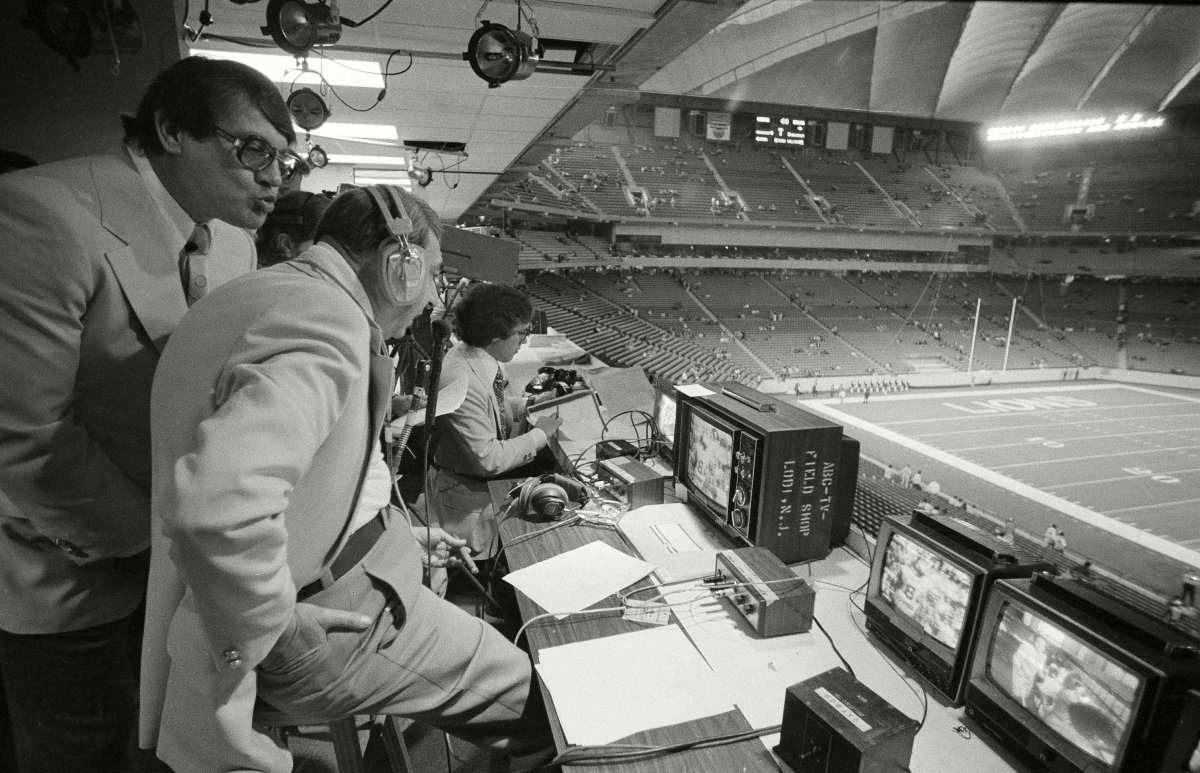

Whatever Meredith lacked in polish was, frankly, good for business. The standard broadcasting booth in 1970 consisted of a staid play-by-play man and a milquetoast retired athlete providing color. But while Arledge was intent on breaking the mold, he had to concede that with Meredith and Cosell he’d need someone to play traffic cop, not to mention actually describing what happened on the field. For this he settled on Keith Jackson, a jack of all trades on Wide World of Sports who’d done play-by-play for college football and AFL games.

When it came to the tone of the broadcasts, Arledge viewed MNF as the perfect place to go big. He would use nine cameras—not three or four, as was the custom of the time—with a second unit dedicated to replays. They would tell stories. “I hesitate to say it—even whisper it—but I was thinking about women,” he wrote. “The other half of the viewing audience.”

While it’s certainly patronizing to suggest that women needed the game to be presented differently, the fact remains: Audiences in 1970 were overwhelmingly male—not surprising, given that coverage of women’s sports was practically nonexistent, much like opportunities for women to play. If Arledge never came out and said that women wouldn’t or couldn’t follow football, plenty of others were happy to. Like Bills running back O.J. Simpson, who before the ’70 season said, “Normally football is a complicated sport for women to understand. ... With more sophisticated use of the isolated camera and other special techniques, they should pick up the game pretty quickly.” Or the television writer for the San Mateo County Times who, when CBS aired one of its Monday-night games in 1966, wrote, “But when the evening dishes are done, mama is entitled to a bit of entertainment on TV. She may not like the invasion of football into night-time programming, such as Monday evening. She can kick up quite a fuss when she puts her mind to it.” (There would be plenty more condescension to come.)

In 1970, Arledge’s MNF team came together for the first time in the booth during a warm-up between the Lions and the Chiefs. That game didn’t air, which is just as well. Meredith was so put off his game by having a voice in his ear, dissecting his performance in real time, that at one point he took out his ear plug, threw it to the ground and barked, “F--- this. These guys are crazy.” Following a tape session the following day, he announced he was quitting.

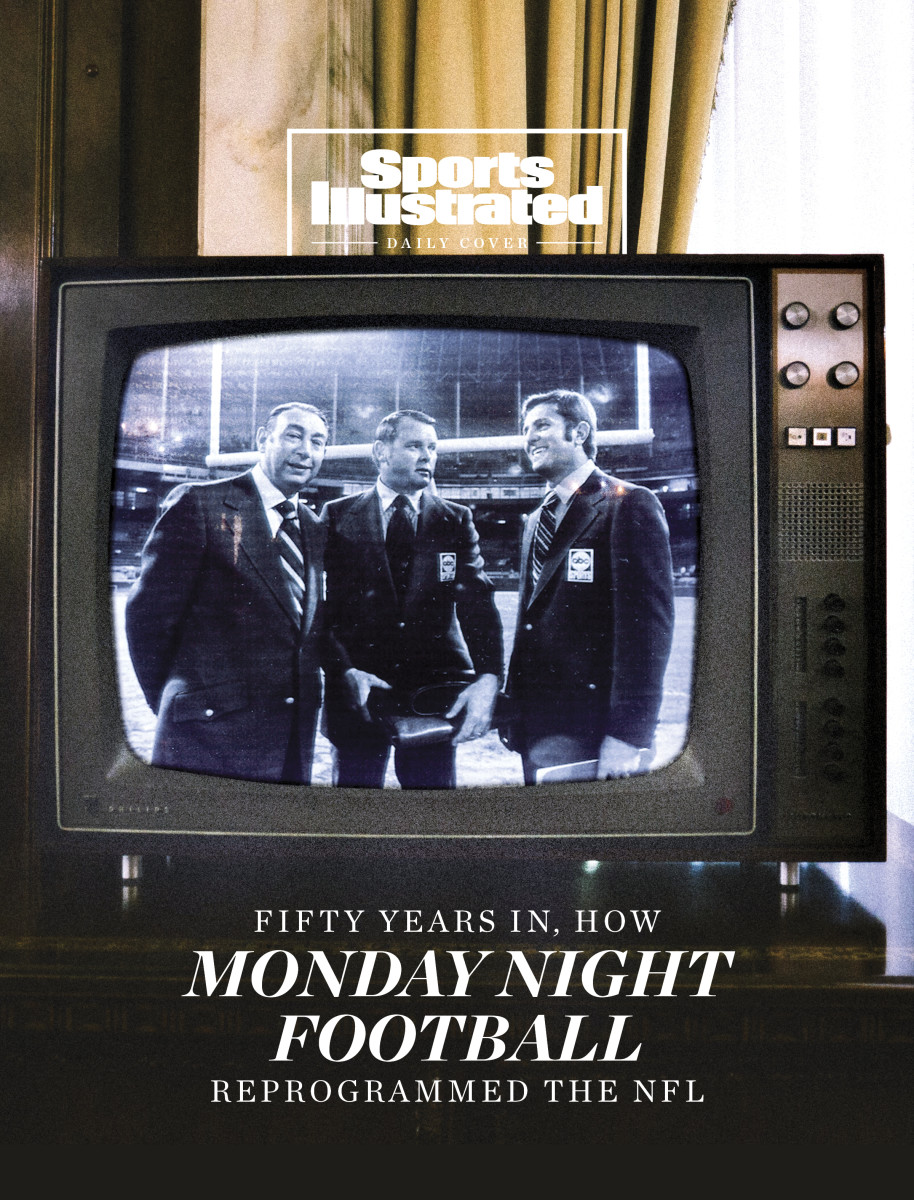

Ultimately, Cosell tracked down his new partner and, over drinks, offered a pep talk, telling Meredith that his own presence would help make Dandy Don a star. “You’ll wear the white hat, and I’ll wear the black hat,” Cosell said. Meredith stuck around, and after a televised dry run of an exhibition game between the Steelers and Giants, it was off to Cleveland.

***

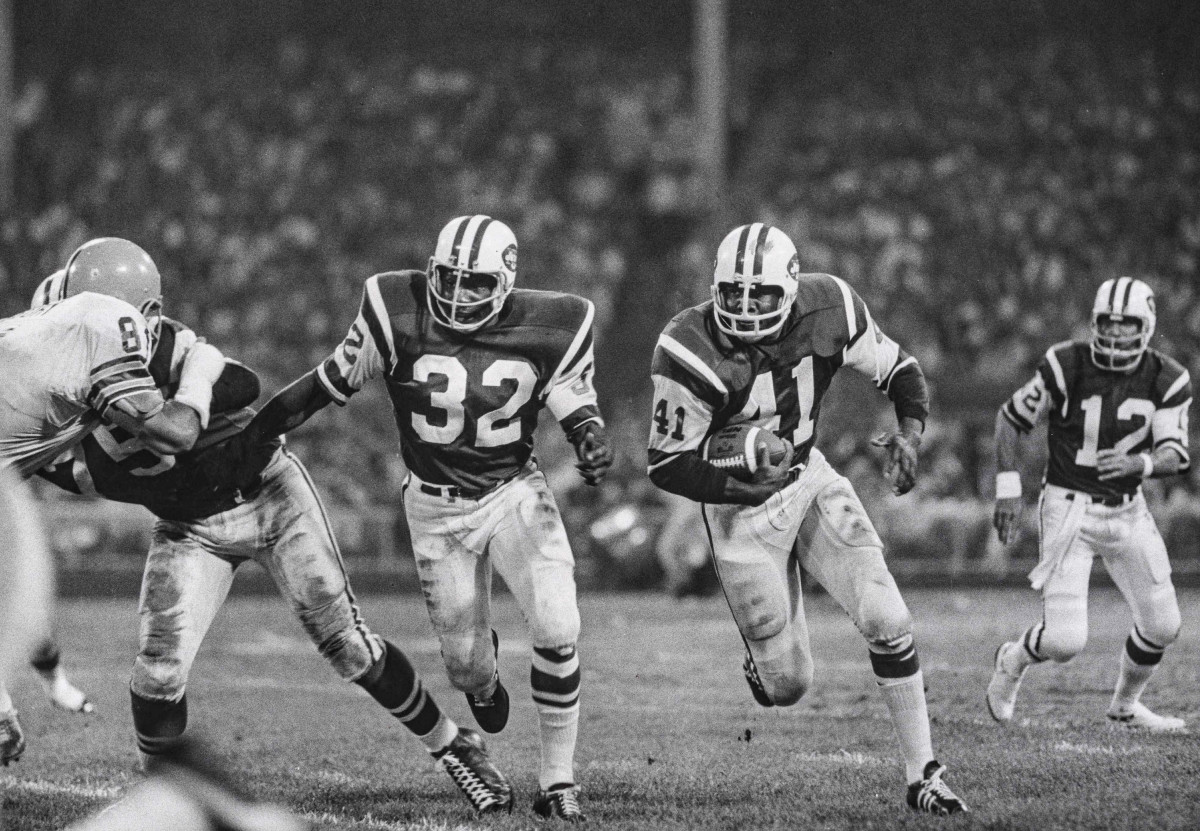

Anticipated as that initial MNF broadcast was, the game itself—capping off Week 1 in the first season after the AFL-NFL merger—looked on paper to be a potential classic. Cleveland had come up just short of the Super Bowl in each of the previous two seasons, and the Jets were one year removed from their upset of the Colts in Super Bowl III. (Never mind that in a fashion predictive of both franchises’ futures, the game would feature 262 penalty yards, the Browns would go on to finish .500 and the Jets would wind up 4–10.)

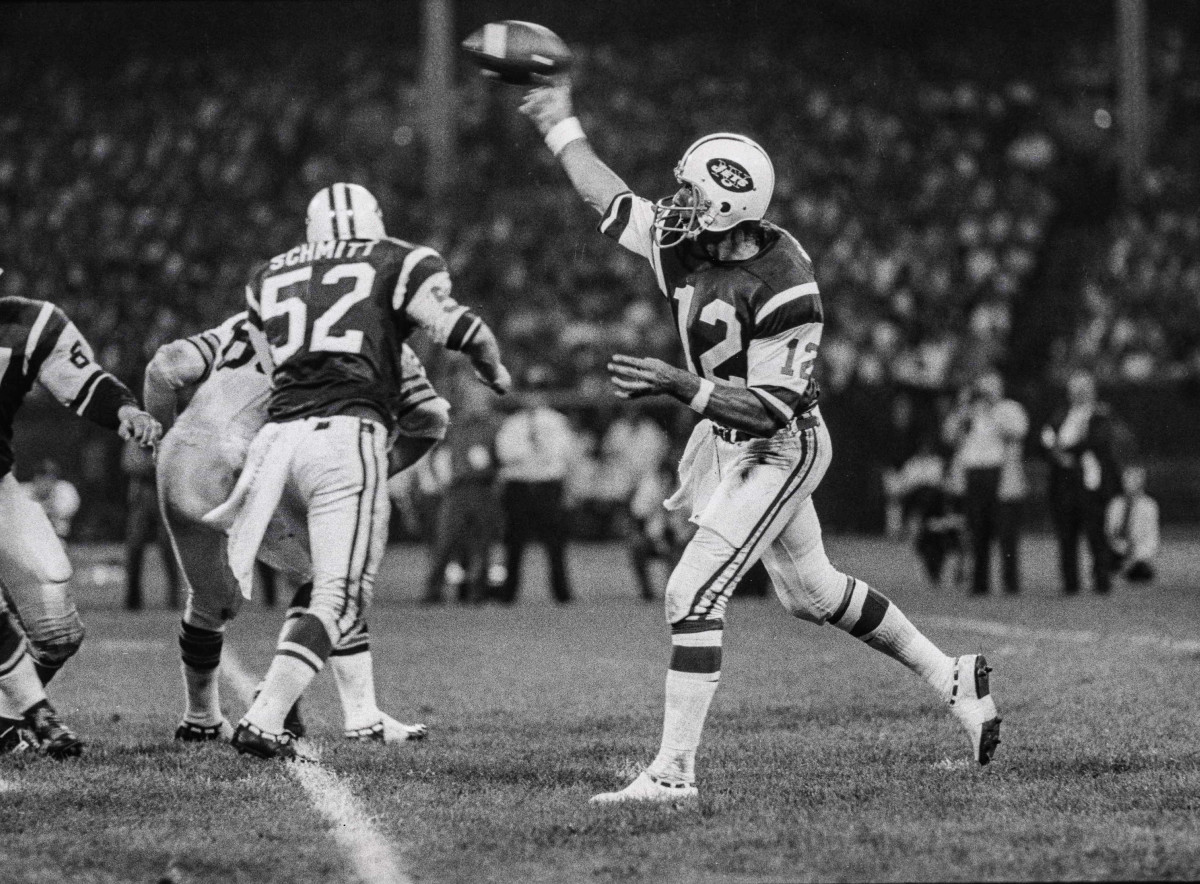

The offseason had been eventful for both teams. In January, the Browns traded All-Pro receiver Paul Warfield to the Dolphins for Miami’s first-round pick—no. 3, eventually used on Purdue quarterback Mike Phipps—marking the first in a long line of questionable draft-day trades by Cleveland. And the Jets were dealing with the drama that came when defensive captain Al Atkinson retired in August, at 27, citing disillusionment with star quarterback Joe Namath’s dedication. (“What really disgusts me is this quarterback not thinking for a minute about the married men on the club, the guys with responsibilities, the average little guys who have families to worry about,” Atkinson said. “That extra money in January means something to them. Not to him. He has his.”)

Atkinson unretired only a few days later, and, before kickoff in Cleveland, Cosell arranged for an interview with both Jets players. Looking like a man forced to read his own obituary off a cue card, Atkinson declared, “I’m glad that Joe Willie’s back with us.”

Then Namath offered up a platitude about the team needing to prove itself, and Cosell introduced Meredith, queuing up a montage of lowlights from the Cowboys QB’s playing days. (Ah, that black hat.) Meredith gamely laughed it off. “I didn’t know y’all were gonna do that,” he said at the end of the clip, launching into his pregame analysis. “I was all set to tell you about those two quarterbacks, and I’m gonna do it anyway. I’m gonna tell you about Bill Nelsen with the Browns and Joe Namath with the New York Jets. In my opinion they’re both leaders, but they do lead in a different way. Bill Nelsen is a consistent leader of the Cleveland Browns, who have been known in the past two decades as probably the most consistent football team in football ...”

Say this: It was consistently awkward.

For all the talk of the three-man booth, a strange thing happened once the game started: No one except Jackson spoke until after the Jets received the kickoff, went three-and-out and punted. And he gave just the specifics of each play, like a very good high school P.A. announcer. Cosell was presumably making his way back up from the field; Meredith’s quiet is a mystery.

Then the replays started, and Meredith showed a knack for providing actual insight. On Cleveland’s second TD—after Collins scored the first on an eight-yard post pattern—Meredith explained how Nelsen had called an audible to have Bo Scott run left instead of right, while the screen showed the play from a novel angle, wide from the opposite end zone.

But the exchange that most clearly validated Arledge’s tinkering had come a few minutes earlier, during a lull between plays.

Jackson: “And I think you can tell now that Municipal Stadium in Cleveland, Ohio, during football season is a cacophony of sound.”

Meredith: “What in the world is that?”

Jackson: “I got that from Howard.”

Meredith: “Between you and Howard I’m not going to be able to understand anything y’all say.”

It was light, it was unforced, and it allowed everyone’s personality to come through.

Watch the Browns-Jets opener from 1970

***

If Arledge’s intention was to make the game more palatable to female viewers, the advertisers—who paid $65,000 a minute and bought up all of the airtime back in July—didn’t appear to have received the message. At the end of the first quarter ABC aired an ad for Goodyear Polyglas tires. For the first few seconds, a couple of men talked about how many miles they put on their tires, then a voice-over intoned, “But Polyglas means more than mileage when your wife has to drive alone,” cueing a bizarre tableau in which a woman on her way to pick up her man at the airport confronted a host of would-be obstacles, set to eerie music that might have been lifted from a bad Halloween ripoff. Lights in the rearview mirror! Detour signs! Pedestrians in a crosswalk! After finally reaching the terminal—phew!—the woman slid over to the passenger seat and let her fella drive home.

In certain newspapers, the commentary the next day was just as bad. Jack Chevalier—whose tire of choice was almost certainly the Polyglas—wrote a column for The Baltimore Sun about a fictitious wife harping at her husband for wanting to watch the game instead of the Richard Burton–Liz Taylor movie on NBC. (“ ‘What’s this jazz?’ screamed Gladys, threatening to scald Harry’s hairy legs with her red-hot iron.”)

But in reality, women were watching. As the season wore on, MNF became a legitimate phenomenon that attracted everyone. Fully one-third of the TV audience—or five million people—was female. The firm of Foote, Cone and Belding surveyed women in six major metropolitan areas and found that while most weren’t sports fans, 75% liked Monday Night Football. And anecdotal evidence backed that up. Mrs. Orville W. Mayberry of Kansas City told the AP, “Football comes first at our house. I’m amused at stories some husbands tell of the wives nagging them about watching football on TV. Well, my husband’s wife beats him to the TV on Sundays and Mondays.”

Monday Night Football even impacted those women who chose not to watch. According to The Boston Globe, one movie theater chain ran a promotion called Women’s Liberation Monday, giving ladies a ticket discount—in effect liberating them from football. It was a canny bit of marketing, because Variety reported that theaters were taking a huge hit on Monday nights—especially those that showed “nudie” films—to the point that some cinemas considered shutting down during NFL games. Similarly, bowling alleys saw their business fall off so precipitously that many moved Monday leagues to different nights.

In the days before the advent of the sports bar, taverns felt a pinch too. “It’s lousy on the bar business,” one Denver proprietor told the AP. “Everybody comes in for a few drinks, then rushes home for the game on TV.” Other establishments breathlessly announced that they were setting up televisions in dining areas.

In Maine, one sportscaster reported the formation of clubs where “groups of between six and 12 people band together to watch the football game at either a favorite pub or in someone’s home.” At his own house, he said, “10 men each bring in six-packs and settle down for the evening’s entertainment.” That apparently wouldn’t fly with one insurance salesman in Long Beach who built a $3,000 den so no one would bother him on Mondays. Yes, thanks to MNF, America discovered two of its most enduring masculine endeavors: male bonding and the man cave.

As the Mondays went on, at least one bar with a television started a contest in which the winner was allowed to throw a brick at the TV set when Cosell appeared. While Meredith had emerged as the breakout star, Cosell was, predictably, the lightning rod. He had his supporters, of course, but a poll of Football News readers found that 80% opted for choice No. 2 in a love-him-or-hate-him poll. Cosell, who made $300,000 a year, was especially unpopular among print journalists, whom he liked to refer to as “$180-a-week mediocrities.” The estimable Jim Murray called Cosell “the man of a thousand syllables,” who “speaks with the deliberation of a guy who has an arrow in his chest” and “treats the game as if it were a pointless interruption of a brilliant monologue.”

In November, a critic at the Louisville Courier-Journal wrote: “The Cosell Agnewism is a fingernail down the blackboard of Don Meredith’s soul, thus the drama from Monday night to Monday night is not only on the football field, as new tests of Meredith’s patience unfold.”

Three days later, during a Giants-Eagles Monday nighter in Philadelphia, Meredith got a new test all right: Cosell, after slurring his way through a halftime segment that ended with him pronouncing the City of Brotherly Love’s name as Fill-elf-a, barfed on Dandy Don’s Cowboy boots. Cosell blamed his heave on a combination of “toxic vertigo” and the pregame sprints he’d run in the cold with John Carlos, asserting that he’d never been drunk in his life. Pretty much everyone else, though, tended to attribute it to the time he’d spent drinking martinis at a pregame party hosted by Eagles owner Leonard Tose. Afterward, Arledge told Cosell to get in a cab and go home. Cosell went to the airport and, finding there were no more flights to New York, hopped in a taxi, asking the driver to take him back to Manhattan, where he crashed until his radio show the next morning.

The incident, ultimately, wasn’t as scandalous as it could have been, but it came at a time when Cosell was wavering in his commitment to the cause. After Arledge yelled at him in Week 2 for needlessly speculating that injured Chiefs running back Mike Garrett would return (he didn’t), Cosell simply stopped talking, barely saying a word for the entire second half. Between the heat from critics, the pressure from sponsors (which Arledge, to his credit, fiercely resisted) and the Philly affair, Cosell seemed like a man who’d had enough. Late in the season he told a group of SMU law students that he would “probably not” return in 1971 because of travel and the fact that “I find the format frustrating. The thing that surprises me is that I’ve created so much publicity for the telecasts under conditions in which I have not been able to do my thing.”

In the end, though, Jackson was the one who didn’t come back. Presented in the offseason with the chance to hire Gifford, now a free agent, Arledge jumped. Jackson was salty, but Arledge softened the blow by finding him the perfect landing spot: college football, where he was the star of the network’s coverage over the next 30-odd seasons.

With Gifford, MNF had its classic three-man booth. The lineup solidified the program’s place in U.S. sports history, fulfilling the promise first glimpsed in Cleveland and serving as a fitting legacy for Arledge, who left to run ABC News full-time in 1986 and died in 2003, at age 71.

Even though he doesn’t remember it, the game has always been huge for Collins, the only member of the NFL’s 1960s All-Decade Team who hasn’t yet been inducted into the Hall of Fame. “Last year they were talking that I was gonna get in,” he says. “But that catch in the first Monday Night Football game—I got pictures made up of it. To [fans], that picture is far greater than anything I did in my career. When I give that to people, it’s like I gave ’em a brand-new Cadillac. They treasure it.”