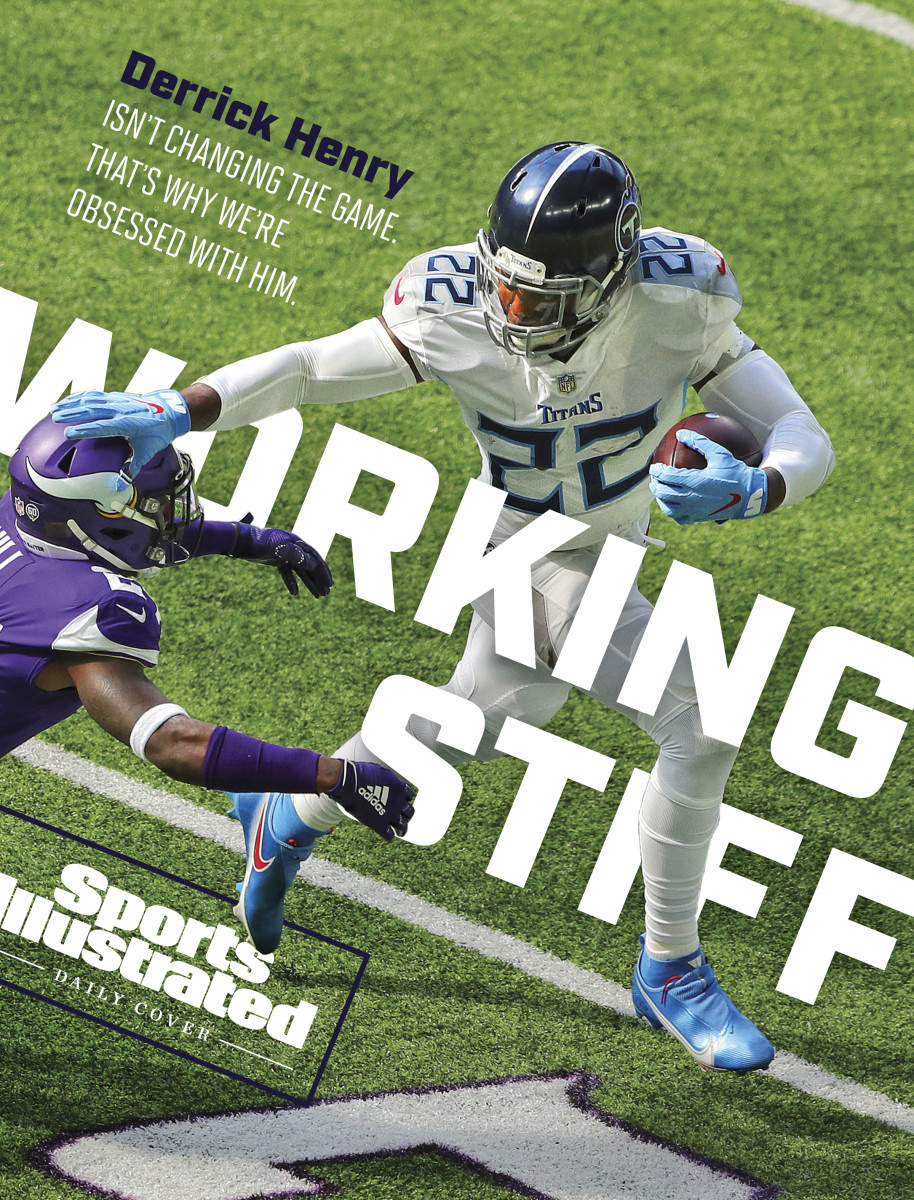

Derrick Henry Isn't Changing the Game. That's Why We're Obsessed With Him

Just try not to click play. It doesn’t matter what words precede Derrick Henry and stiff-arm in the video description. Crazy. Filthy. Lethal. The mere mention of name and maneuver is enticement enough.

The NFL finds itself increasingly tilted toward the offensive highlight, and big-play moments abound, from 60-yard deep shots to sideline-skimming back-shoulder ballets. But while such offerings might make more difference in terms of immediate yardage, they can’t quite match the guttural appeal of the Titans running back’s signature move. A defender tries to tackle Henry and is denied in as straightforward a syntax as body language allows.

Over five seasons, Henry has built up a catalog of such moments, with all sorts of variations. He’s pushed defenders out of his way with a flick of his hand or with a statuesque shove, in the regular season and in the playoffs, in tight games and in blowouts. Here’s an example—definitive for almost anyone else, ho-hum for Henry—from the opening drive of Tennessee’s crucial Week 12 win over the Colts, in which he ran for 178 yards and three touchdowns. Quarterback Ryan Tannehill pitched the ball left and the Titans’ line fanned out, but defensive tackle Taylor Stallworth snuck through, taking clean aim at the back. At the point of contact, Henry snapped a palm into Stallworth’s facemask, which had the effect of a straight right hand to the chin of an encroaching boxer, dropping the defender and opening the edge for a 12-yard gain and a first down. At 300-plus pounds, Stallworth outweighs every back in the league, but this outcome somehow didn’t register as a surprise. "Henry … stiff-arm … turns upfield," was all CBS announcer Ian Eagle needed to say.

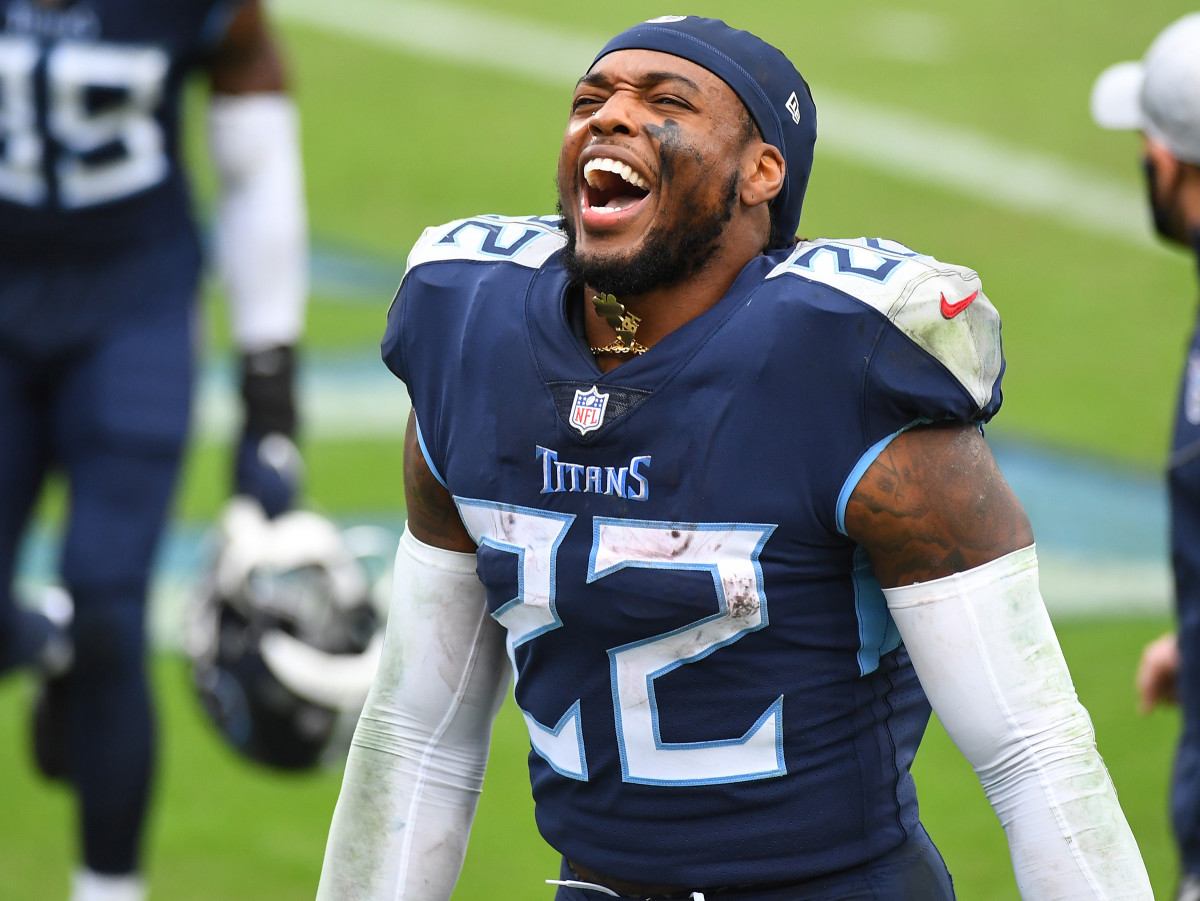

Tennessee’s recent upswing—from perennial 9–7 afterthought to last year’s postseason revelation to a place among this season’s contenders—has been a cooperative effort. Tannehill is a play-action maestro, second-year receiver A.J. Brown a threat in every facet of the passing game, Mike Vrabel the rare Bill Belichick disciple to transplant some measure of the old New England competence. Last January, Tennessee buried the Patriots dynasty and walloped the top-seeded Ravens in back-to-back playoff wins; last month, it handled Baltimore and Indianapolis in consecutive weeks.

Henry remains his team’s best-known player, an uncommon designation for a modern-day running back. Yet he stands for no new strain of strategic enlightenment. Alvin Kamara, the latest Future of the Position, is an angle-busting, pass-catching speedster, capable of cutting in any direction at any moment. Sure, Henry has a never-before-seen element, but his is mostly a difference of degree, not type. At 6’ 3” and 247 pounds, he’s as big as some defensive ends, and his breakaway speed of nearly 22 mph ranks among the best in the NFL, at any position. His limbs look hydraulic. He is as daunting a power runner as exists in today's pro football. But he is still a power runner.

In terms of multidimensional significance, Henry isn’t the back you’re looking for. His 114.3 ground yards per game—he is one of just three players averaging triple digits—almost count against him, a sign of obsolescence. But for raw viewing spectacle? “Normally, in the NFL, you’re talking about the slightest of differences in athletic ability and dexterity,” says Eagle. But “when someone is so dominant in that manner, it’s hard not to notice. He’s a wrecking ball.”

Even as the Titans push their way into any talk about title hopefuls, Henry’s runs tend to draw attention not for what they accomplish but for what they mean. Every sport is sleeker and smarter than it used to be, concerned less with direct confrontation than with strategic outflanking. And so the Derrick Henry stiff-arm, with its proud heritage, and in all its bruising incarnations, has the special allure of something edging toward extinction.

***

The move is as old as football and, like so many elements of the sport, more complex than the catchall term suggests. Great practitioners of the stiff-arm, over the years, have shared certain attributes—an innate understanding of angles and timing; an awareness of the relationship between force and balance, strong hands and driving thighs—but applied them differently. Jim Brown ran like a wave, the occasional outthrust palm just one ripple of a general momentum. Earl Campbell looked like he wanted to crack helmets. LaDainian Tomlinson’s stiff-arm was tempo. Marshawn Lynch’s was nastiness.

The maneuver may look purely reactive—Get away!—but it is also, often, studied and mastered. “If you break it down into science and geometry, it really involves angles,” says Tomlinson. The 2017 Hall of Fame inductee loved the stiff-arm all the way back when he was a Pee Wee, but it was the tutelage of Chargers running backs coach Clarence Shelmon that helped him hone it. Before that, in his college and early NFL days, Tomlinson always aimed his hand at his opponent’s head (a photo of him wedging his mitt under the facemask of the Rams’ Oshiomogho Atogwe, de-helmeting the St. Louis safety, is one of the enduring images of his career), but if a tackler hunched in delivering a hit, Tomlinson’s hand would sometimes slip uselessly off the crown. Shelmon taught Tomlinson to vary his aim, accounting for leverage and the direction of the defender’s approach.

The Chargers assistant assigned film: Brown, Gale Sayers, Walter Payton … Tomlinson remembers watching highlights of Eric Dickerson, keying in on the instant just before the Hall of Fame back met a defender. “He would do a little juke and then throw the stiff-arm,” Tomlinson says, describing a move that tended to compromise a potential tackler’s balance right before impact—a move that eventually figured heavily in LT’s own open-field arsenal.

“My philosophy was: Make it a surprise,” says Shelmon. “Let them think they got you. Then, all of a sudden, you shock them. You become the aggressor.”

At Henry’s size—five inches taller and 30-odd pounds bigger than Tomlinson—this all gets a little easier, as much force as technique. “He simply opens his hands and pushes defenders down,” says Shelmon. But Henry didn’t develop a taste for the stiff-arm as early as Tomlinson did, even if he’d matured physically by his teens.

“He wanted to be a run-around-you guy,” says Bobby Ramsay, Henry’s coach at Yulee High, outside Jacksonville. “We had to tell him, ‘Hey, dude: You know you’re really big?’”

Ramsay, too, steered his pupil to the tape. Henry watched Dickerson and Eddie George, the mammoth Titans All-Pro, both of whom had the kind of edge speed he found appealing—an ability to beat a defense to the perimeter when it bunched against the offense’s strength—and an understanding of when the situation called for something more straightforward.

Henry ran for 12,124 yards across his four years at Yulee, a national record, due in large part to his coaching staff’s success in convincing him of the virtues of contact. Teams would stack their defenses against Henry, sending nine or 10 players within a few yards of the line, but so often that plan backfired. “We loved that,” says Ramsay, “because all he had to do was make one guy miss, and then he was gone.”

On many evenings, such as the one during Henry's senior year when he piled up a state-record 510 yards, the formula made for unstoppable football. Ramsay recites the pattern happily: “His track would be, [hit the] B gap”—between the offensive guard and tackle—“bounce to the linebacker, get toward the hash marks and stiff-arm the free safety.”

Henry’s success as a pro has come by way of an adjustment to that up-the-middle approach, which seemed such a natural fit at Alabama, too, where he won the Heisman Trophy and a national title during the 2015 season. Staggering though those results were, the logic—big guy, run him straight ahead—didn’t make the best use of his exclusive place on football’s size-speed matrix. The Titans prefer stretch zone plays, outside runs that let Henry strafe past the edge of the line-of-scrimmage muck and gather momentum. Where between-the-tackle plunges often end with a running back addressed head-on by a linebacker, these plays set up the advantageous scenario of Henry meeting defensive backs who approach from his side, ripe for their casting off.

“They don’t want to see him when they’re running downhill and he’s coming at an angle, when he can throw his stiff-arm,” says Tomlinson, now an NFL Network analyst, of those last unlucky safeties or corners. “They’re at his mercy.”

Case in point: Last January, in that divisional-round game at Baltimore, the Titans’ front cleared out a row of Ravens linemen, offering Henry a cutback lane to the right. He took it, popping out of an arm tackle and picking up speed, knees pumping and eyes widening at the prospect of open grass. The first player with a legitimate shot at him, racing in from his left some 15 yards downfield, was Earl Thomas—an All-Pro safety, maybe the best of his generation, but a safety nonetheless, 45 pounds lighter than the man he would be trying to bring down. Henry first shot a hand into Thomas’s shoulder with such force that the poor DB spun around, off balance, finding himself suddenly running several steps ahead of Henry, in the same direction, just trying to stay upright. Thomas’s momentum seemed for a moment suggestive, as if he were fleeing, at which point Henry shoved him again in the back. When both men finally crossed the white of the sideline, 27 yards from the line of scrimmage, players on the Titans’ bench were visibly torn between celebrating their teammate’s gain and basking in the defender’s humiliation.

That Thomas hadn’t fallen, as most players do at Henry’s hand, didn’t diminish the highlight. To the contrary, it emphasized the sense of dismissiveness that colored the play, the totality of Henry’s advantage.

The King is hitting his stride. @KingHenry_2 #Titans #NFLPlayoffs

— NFL (@NFL) January 12, 2020

📺: #TENvsBAL on CBS

📱: NFL app // Yahoo Sports app

Watch free on mobile: https://t.co/81PYwJcw9t pic.twitter.com/55GW6ctQCE

Asked for the purest example of his former player’s abilities, something that suggested the career to come, Ramsey selects a similarly placid play, a long run from Henry’s junior year, when he reached for an incoming defender and, without breaking stride, ushered his opponent down to the turf. “You didn’t hear the person make a noise when he hit [Henry], or contact with the pads,” Ramsay remembers. “It was just real quiet.”

***

In Henry’s NFL, there are two surefire ways to win fans' adoration. One: represent something new, an as-yet-unexplored frontier of the sport. (The league is presently packed with such innovators. Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson, DK Metcalf—if you want to see a ball or body move in ways that seemed unimaginable a half-decade ago, you’ve got your pick.) Or two: bring something back into fashion. For fans too young to have watched Brown and Sayers and Campbell—maybe even more so for those who were around—Henry offers a glimpse of something near to the soul of the game.

Football’s history is defined by revision. Revision in pursuit of safety, or of entertainment, or of some uncomfortable amalgamation of the two. Standard techniques eventually become casualties of progress, like linked-arm wedge blocking at the turn of the 20th century, or certain variations of the crackback block in the 21st. “Look at the first couple years of what we considered college football and it’s almost a completely different game,” says Jeremy Swick, a historian at the College Football Hall of Fame. The stiff-arm, though? It has endured through rulebook changes and evolving strategies. “It’s one of the few [aspects] that have just been there.”

Nitpickers have floated concerns from time to time. It is true, there exists something of a double standard: Whereas a defender is penalized for hooking even a single digit around a ball carrier’s facemask, a runner is essentially given carte blanche to mash, twist, lever or otherwise bombard the entirety of a tackler’s helmet. But the real threat to the stiff-arm lies not in its legality. The threat is a change in style. Teams run less frequently this decade than they have ever before. Factor out the end-arounds and gadget plays that have proliferated in recent years, and the number of rushes drops further still. Most organizations prefer quick, versatile backs over power runners, who tend not to fit in the spread-‘em-out dogma.

The popular attachment to Henry—the internet clamor whenever he turns a defender into a refrigerator box—suggests an appetite for elements in short supply within today’s game, starting with the simple concept of force. Opinions differ as to the effectiveness of the NFL’s recent efforts to protect players, but a shift of some sort is undeniable. A safety no longer has free rein to ram his shoulder into the helmet of an unaware receiver; a defensive end must steer the quarterback to the turf with care. Whether or not these restrictions actually keep players healthier, they clearly remove a layer of visible ferocity from the game.

“The essential appeal of football is a tension between violence and beauty,” says Michael Oriard, who spent four years in the 1970s playing on the Chiefs’ offensive line, and who has passed much of the rest of his life thinking about the game, teaching at Oregon State and authoring several books about the social draw of sports. “The artistry wouldn’t be nearly so artful if there wasn’t a constant threat of violence.”

The stiff-arm is a living relic from football’s vicious evolution. It is not especially dangerous, all told—the primary effect of a well-executed stiff-arm tends to be a healthy dose of embarrassment—but it nevertheless revives an antiquated attitude. It makes a case that football remains, at its root, a contest between people trying to move one another backward.

“Fans tend to like one-on-one, out on an island,” says Eagle. “There’s something about that visual that’s appealing: this guy against that guy, and someone is going to win. It’s this mini battle within the game.” In real time, the average viewer will see the spectacle of a long pass but not the intricacies that made it possible: the patterning of play calls, the pre-snap motions and checks, the route combinations peppered with misdirection, all of it modified in response to coverage. The ball disappears through the top of the TV screen and lands in someone else’s arms; replay analysis comes along to fill in the gaps. If the ground game is no less complicated—a compact and quick-hitting negotiation of leverage and numbers—it often looks so, especially when a play leads to a ball carrier knocking over the man in front of him.

Passes win hardware, but runs win our hearts. A generation of football fans can easily picture Lynch’s 67-yard “Beast Quake” touchdown for the Seahawks, in January 2011 against the Saints, in all of its brutal detail: the first explosion through the line, the moment when he looked corralled, the abrupt escape into open field. The zenith—you could see it coming—when Lynch put the heel of his hand into Tracy Porter’s chestplate and sent the DB crashing. (If a whole body can take the shape of a snarl, Lynch’s did so here.) Seattle, 7–9 during that regular season, bowed out of the playoffs the following week, but it didn’t matter: The memory was already bronzed. One year ago, as part of its centennial celebration, the league ranked Lynch’s run as the 13th greatest play in NFL history.

***

There is a lingering feeling that Derrick Henry not only carries on a tradition but also, perhaps, heralds its endpoint. The only runner selected in the first round of last year’s NFL draft, with the last pick, was the short and shifty Clyde Edwards-Helaire, by the Chiefs. Across the league, the reputations of load-carrying rushers have suffered. With Ezekiel Elliott taking a lead role in the absence of an injured Dak Prescott, the once-promising Cowboys have lost five games and won one. David Johnson, in being traded for DeAndre Hopkins and thus inviting a comparison with the otherworldly receiver, has been reduced to a punchline. The Rams ditched Todd Gurley and got better.

Henry is, without much question, the best in the world at what he does. He leads the NFL in net rushing yards (1,257) and yards after contact (743, which on its own would rank sixth in pure rushing totals league-wide). Despite his relative deficiencies in route running and pass catching, he is graded by Pro Football Focus as the second-most effective running back in the league, a testament to how much he has set himself apart within his specialty. However: Accounting for the relative value of each position, he is but a tertiary figure in the Titans’ offense, less important, for sure, than Tannehill (PFF’s 10th-best quarterback) or Brown (whose average catch goes for 16 yards, ninth-best in the league).

Henry’s excellence is enough to make him relevant, but not central. When the Titans pass, they are “roughly 50% more efficient than an average [NFL] offensive play … and the results match an average offensive play when they run,” says Aaron Schatz, the founder of Football Outsiders. “That’s just how much more efficient passing is than rushing; it naturally limits the value of a running back. This is different from saying [Derrick Henry] is not an impressive athlete or he doesn’t work hard—this is just how it is.”

When the Titans go into their two-minute offense, a scenario in which an all-purpose back like Kamara might split out wide to test the ligaments of some poor linebacker, Henry often jogs to the sideline. One of Tennessee’s signature wins this season came when Tannehill led a closing-minute touchdown drive against the Texans, capped by a fade to Brown in the end zone’s far corner with seconds remaining. Henry was off the field for that series, returning to ram the ball across the goal line in overtime.

The running back fraternity maintains that advanced statistics (and the general preoccupation with versatility) miss an important part of what someone like Henry provides. A physical run game “becomes the passion, the heartbeat of a football team,” says Tomlinson. “It’s good, sometimes, to have that long pass—that’s nice, everybody likes it—but what football players truly like is knocking a man back against his will, and the back coming through the hole, making a big run. It demoralizes a defense.”

Maxims like these have a certain felt logic, but they’re impossible to measure; players don’t yet wear endorphin monitors under their pads. Analysts have tackled the question, though, of whether there are benefits in the play-action game from establishing the run, and they’ve found this notion mostly to be a myth. The power-run game is no longer a foundation; it is a wrinkle, a tax levied against defenses hedging too hard against downfield shots. Henry might be the soul of the Titans’ locker room; he may well imbue his team with some unbeatable mojo. On the field, however, he is a supersized, dynamic, impossible-to-believe complement. In the words of Pro Football Focus data scientist Lau Sze Yui: “Tannehill helps Henry more than vice versa.”

What football fans feel when Henry does his thing, though, has nothing at all to do with win-expectancy charts or efficiency-maximized playcalling. If anything, to celebrate his domination is to abdicate the logic of optimization through which football is increasingly filtered. A stiff-arm isn’t cool because it opens up new avenues for tactical expansion. It is cool because of the vicarious thud you experience when you see it.

In mid-October, against Buffalo, Henry took a handoff and set to his preferred route, gliding to the left edge and angling upfield. Bills cornerback Josh Norman mirrored Henry’s movement and succeeded in stringing the back out—the two met where the sideline and the line of scrimmage form a T—but then Henry activated that right arm, which behaved like a demolition excavator: steady motion, irrefutable effect. Norman went flying. Still images of the play show the DB horizontal, at Henry’s waist, bracing for his return to earth.

Henry gained four or so yards, close to a first down, but the run didn’t count; offsetting penalties nullified the play. But who cared? Certainly not the NFL, whose YouTube page hyped “Derrick Henry’s MONSTER Stiff-Arm.” And not the fans who posted muscle and coffin emojis (in mock memoriam of Norman) in the comments. And not Vrabel, who afterward called the non-play “the best five-yard run I’ve ever seen.”

Henry’s moment of glory, erased from the official ledger, did nothing to help the Titans win the game. But it’s what everyone remembered.