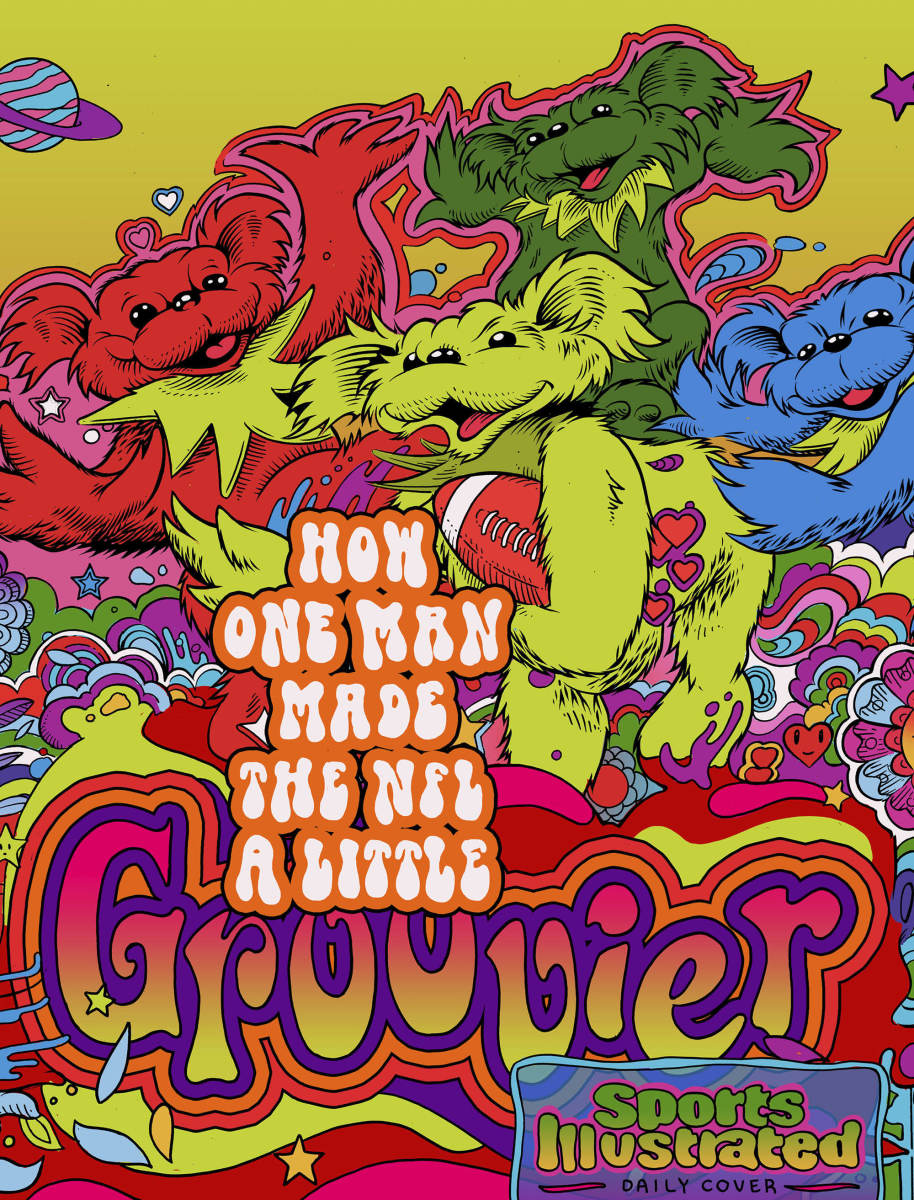

Phish-and-Football Thursdays? Credit (or Blame) This Guy

As the Bills and Chiefs went to their first television timeout during a pandemic-altered (5 p.m. ET) Monday night game back in mid-October, most of the football world heard announcer Joe Buck ease into commercial with an otherwise banal comment about a forgettable punt: “The Bills have it for a second time on a rainnny night in Buffalo. ...

But for a small subset of the NFL audience, this moment was more memorable than the game itself. As the bumper music beneath Buck’s voice kicked in, football fans of a certain musical persuasion would have recognized the layered guitar strums, backing horns and signature riff of a song called “Happy Hour Hero,” by the jam band Moe, which formed not far from Bills Stadium.

For the most ardent (and realistic) jam-band fans, the realization came long ago that their favorite songs—which almost never sound the same, even when played on back-to-back nights, and which can stretch over half an hour in length when a band is feeling particularly improvisational—would exist comfortably outside of the mainstream. On social media, some of those fans did recognize the deep cut, and they tagged Fox’s Troy Aikman, delighted by the idea that perhaps the Cowboys legend secretly admired an obscure track from a 1998 album called Tin Cans and Car Tires. On Twitter, one commenter—perhaps not a fan—wondered: “Whose hippie cousin took the aux cord?”

Four hours dead east, meanwhile, Moe was rehearsing that evening at the Palace Theater in Albany for a string of drive-in shows the band was performing during the pandemic. Guitarist and singer Al Schnier, who grew up in Bills country, had his iPad set up in front of his guitar rig, and he was watching Fox with the sound muted as Josh Allen threw three straight opening-drive incompletions—until he started to get bombarded by notifications.

Informed of what had happened, bassist Rob Derhak, the lead singer on “Happy Hour Hero,” says he remembers the moment being cooler than the first time he heard one of his songs on the radio. “We took a break and had this Holy s--- moment,” says Schnier. “What a great thing: Your team. Your song, on a national broadcast. It’s happy hour and they’re playing ‘Happy Hour Hero.’ ... If only the Bills had won.” (Final: Chiefs 26, Bills 17.)

In that moment, only the most zealous of jam diehards knew whom to credit for this blessed occurrence: a Los Angeles-based Deadhead and Phish devotee named Jake Jolivette, who’d worked his way up the production ladder at Fox Sports into a position where he today programs the music as Thursday Night Football games go to commercial break. Gone under his guidance are Jock Jams outros and Top 40 drivel aimed to please the generic masses. Here to stay is something unfamiliar, something more spectacular: the tenured giants of the jam band world, from the godfathers of the genre, the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers; to their heirs, Phish and Widespread Panic; and all of the bands that formed in their wake—Moe, Umphrey’s McGee, the Disco Biscuits… .

TNF, once lambasted for delivering mostly-forgettable, low-impact matchups between teams on short rest, has in 2020 offered a dash of the unexpected with Jolivette, 46, behind the turntables. (The games have been something better than awful too!) Once a week, Deadheads and Dead-haters alike are treated to (or tortured by) an expertly curated playlist containing subtle Easter eggs—lyrical nods and geographic winks, like the aforementioned band’s “Tennessee Jed” during a Titans game, or Georgia-based Widespread Panic while the Falcons play—all baked into a three-hour block of time previously marinated in stale machismo. For the jam community, musicians included, Thursday games are suddenly appointment viewing. Even Buck, who has a direct line to Jolivette during games, has gotten into it: He prides himself on his ability to guess which band just played during a given break. (Aikman has started playing along, begrudgingly, though he mostly asks for more country music. He did recently correctly call a Lumineers song.)

Altogether, it’s a sweet salve for a nomadic fan base that is used to building its calendar around festivals and tours, and that has seen the live-music industry fiercely throttled over the last 10 months. “We miss going to shows,” says Jolivette, who on Thanksgiving Day served up “Stash,” by Phish, and “Saint of Circumstance,” by the Dead, on back-to-back commercial breaks. “Moe was my last show before the pandemic, the second week of March, in L.A. I never knew that would be it.”

The cost, he says, has been a lost sense of “community and family”—which he’s doing his best to provide, albeit in drips and drabs. “It’s unbelievable how that 10-second riff can do that. If people are watching the game and can have that smile, if I can generate that, that’s pretty cool.”

Try, for a moment, to throw out the stereotype of the Birkenstock-wearing, dreadlocked wanderer floating back and forth in a tie-dyed T-shirt; forget the image of the jersey-wearing, sports radio-calling football fan. Think of the people you know who most deeply care about Phish or the Dead or some other jam band, slipping seamlessly from the banalities of the office to the wild, sensory experience of a weeknight show—and think of those who feel the same way about their favorite football team. Now consider the overlap. “The correlations between sports and the jam world run very deep,” says Ari Fink, Sirius XM’s director of music programming and former host of the Jam On channel. (“...A non-stop music festival with live, improvisational, and adventurous rock.”) “[Jam fans] treat music like sports. They look at song statistics. They analyze song development over time, like they’re players. We go deep in terms of research and consumption. And it’s interesting to see [these two worlds] collide.”

Fink says that this collision occurs more often than you’d think, especially in the broadcasting world, where the likes of Bob Wischusen (play-by-play for ESPN and the Jets) commingle with their favorite jam musicians (Umphrey’s McGee bassist Ryan Stasik; Disco Biscuits bassist-singer Marc Brownstein; Revivalists bassist George Gekas) in Fink’s hyper-competitive Jam On fantasy football league. But this collision happens out in the open, too. Take Trey Anastasio, the lead singer and guitarist for Phish, whose song “Wilson'' tells the story of a tyrannical medieval king on the verge of being overthrown. Such is the collaborative nature of the eclectic, expansive and often difficult-to-define jam-band universe, the tune evolved over time to begin on a series of four open E guitar notes, followed by a response from the crowd: Willl-sonnn. And eventually, at a 2013 show in Seattle, Anastasio—a football fan who’d become enamored with Russell Wilson after the Seahawks dismantled his beloved Jets—implored the audience to adopt the Wilson chant at games. Which led to the flooding of the franchise’s inbox with emails, and eventually the playing of Anastasio’s guitar notes at Lumen Field every Sunday, whenever the quarterback first shows his face.

Four years later, in the leadup to Super Bowl LI, Jolivette was scoring a Falcons highlight package, narrated by Ving Rhames, that would play before Fox’s broadcast. With encouragement from some creative, like-minded producers—Jacob Ullman, Fox’s senior VP of production and talent development, for one, is a major Deadhead—Jolivette decided to use Phish’s “Tweezer (Reprise)” as the backing music, and on gameday, when eventually Anastasio’s signature noodling intro arose underneath Rhames’s booming baritone, the ears of casual and hardcore football fans alike perked up.

Peter Schrager, the host of NFL Network’s Good Morning Football and a Fox sideline reporter who counts several obsessed Phish fans among his closest friends, texted Jolivette immediately and asked: “Is this you?”

Jolivette confirmed, Schrager tweeted the identity of the jam-band DJ, and from there his status as a bite-sized musical demigod was solidified. (It helped his reputation, too, when Phish’s touring manager posted on Facebook the text message he received after Anastasio himself heard the nod on TV: “Holy f---. My mind is blown.”) Says Jolivette, who, for what it’s worth, likes to think of himself more like a psychedelic Casey Kasem: “Since then, it’s hilarious. I’ll look at my mentions after a game and they explode. Then the requests come in.”

Jolivette remembers well his first concert, back in 1992, at what was then called the Deer Creek Music Center, outside Indianapolis, where the Grateful Dead were on the third leg of a breakneck tour. Though it was a precarious time for the band—the years leading up to lead singer Jerry Garcia’s death in ’95 were marked by decline and inconsistency—the budding producer was hooked, and he began the kind of progression familiar to fans of the genre, listening to and later traveling to see the likes of Phish and Widespread Panic and Moe and the String Cheese Incident.

“At first you would go to these shows,” he says, “and you would wonder, Why are we going so early just to hang out in the parking lot? Then you saw all these people. You’re a junior in high school and you can’t wrap your head around it. They just travel with the band from city to city? Fast-forward five years and I’m planning out my own Midwest tour.”

That wandering spirit never left him. As a producer for Fox, Jolivette, like the bands he loves, today lives an almost nomadic existence, his schedule dictated by the TNF location, plus a weekend college football game and the occasional NASCAR event. (As it turns out, he says, football fans are, by and large, far more receptive than racing enthusiasts to a sprinkling of the Grateful Dead throughout their broadcasts.)

They've now played Tweezer Reprise, Frankenstein & Free on Thursday Night Football....

— Phishymemes (@phishymemes) December 13, 2019

I'm now counting it as a Phish show and adding it to my total....

That’s part of the intimacy in Jolivette’s connection with the bands he spins and the fans he amps up on his broadcasts. There’s a depth to this relationship that closely mirrors the connection that jam bands often set out to facilitate with their own following.

“We’ve always seen ourselves as a blue-collar working band,” says Derhak, the bassist-singer for Moe, “and mainstream recognition has never been something we were lucky enough to have. I don’t measure success by it, but hearing my song on [Thursday Night Football], that recognition gave me a nice, warm, fuzzy feeling.”

That love is spreading, and Jolivette takes seriously the sense of togetherness he delivers. Before each game he sits inside a surprisingly spacious—and, for now, socially distanced—production truck parked outside of a stadium and during a half-hour meeting narrows down his playlist to 30-odd songs, his jam selections mixed in with mainstream, cheeky favorites, like A Tribe Called Quest’s “Can I Kick It,” to be played on the occasion of an exceptionally long field goal. Each song is numbered in a computer playlist, and when the game veers toward a commercial, Jolivette radios his audio engineer, telling him to fire a particular track into the break.

“There’s nothing like when you’re one minute away from going live,” says Jolivette. “There’s no edit button. There’s no redo. If your heart isn’t pumping, you’re in the wrong business. I’m sure those guys”—the musicians he queues up every week—“when the lights go down and they go on the stage, they feel the same thing, even before show No. 68.”