A Linebacker and His Team in the Year of Athlete Activism

Eric Kendricks jogged onto the turf for the Vikings’ season opener, his long, curly, black hair bouncing atop his shoulder pads, his eyes scanning the most surreal football scene imaginable. The cheerleaders were home, along with the mascots, band members, concession workers and fanatics who normally painted their chests purple and dressed like actual Vikings. The 66,200 seats at U.S. Bank Stadium were silent and sterilized, empty except for the one family spread between adjacent luxury boxes perched above the field.

That family came from Texas, mostly, visiting the city where the worst tragedy that ever happened to them had been broadcast all over the world four months earlier. They arrived Saturday, stayed in a hotel downtown and rode a passenger bus over, settling into the corner end zone above Section 138 and snacking on shrimp cocktails, pizza and cold cuts. The Vikings handed out No. 88 jerseys, the same number their slain relative, George Floyd, wore during his high school football career; compiled a video tribute to him; and chose not to sound the Gjallarhorn for the first time since 2007, calling for a “more unified society.”

Kendricks, a veteran and elite linebacker, desired to find them. Floyd’s death in May had motivated the 28-year-old to build on his social justice efforts this fall, becoming more vulnerable, more involved and more informed—and in a more public way. While in Los Angeles, his offseason home, he first came upon the video of a police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes, the footage so raw and unsettling that he would turn away, turn back, then turn away again. The clip sparked international outrage but resonated in particular in Minneapolis, where Floyd died roughly 20 blocks from the football game taking place in an empty stadium a few months later.

Kendricks had filmed a video as the protests started. It showed him in a dark T-shirt, leaned forward, hands clasped, tears forming in his eyes. “I know there’s a lot of you guys that probably feel similar to me,” Kendricks said. “You feel a little bit helpless, like you can’t do nothing. You want to help, you want to be the change, but you don’t know how to in this situation. It's real deep.” He paused, before detailing how much he cared about his adopted city, the place where he transformed from a shy second-round draft pick out of UCLA to an All-Pro and activist. He asked for accountability, pleaded for everyone to do more and said, “This has gotta stop happening.”

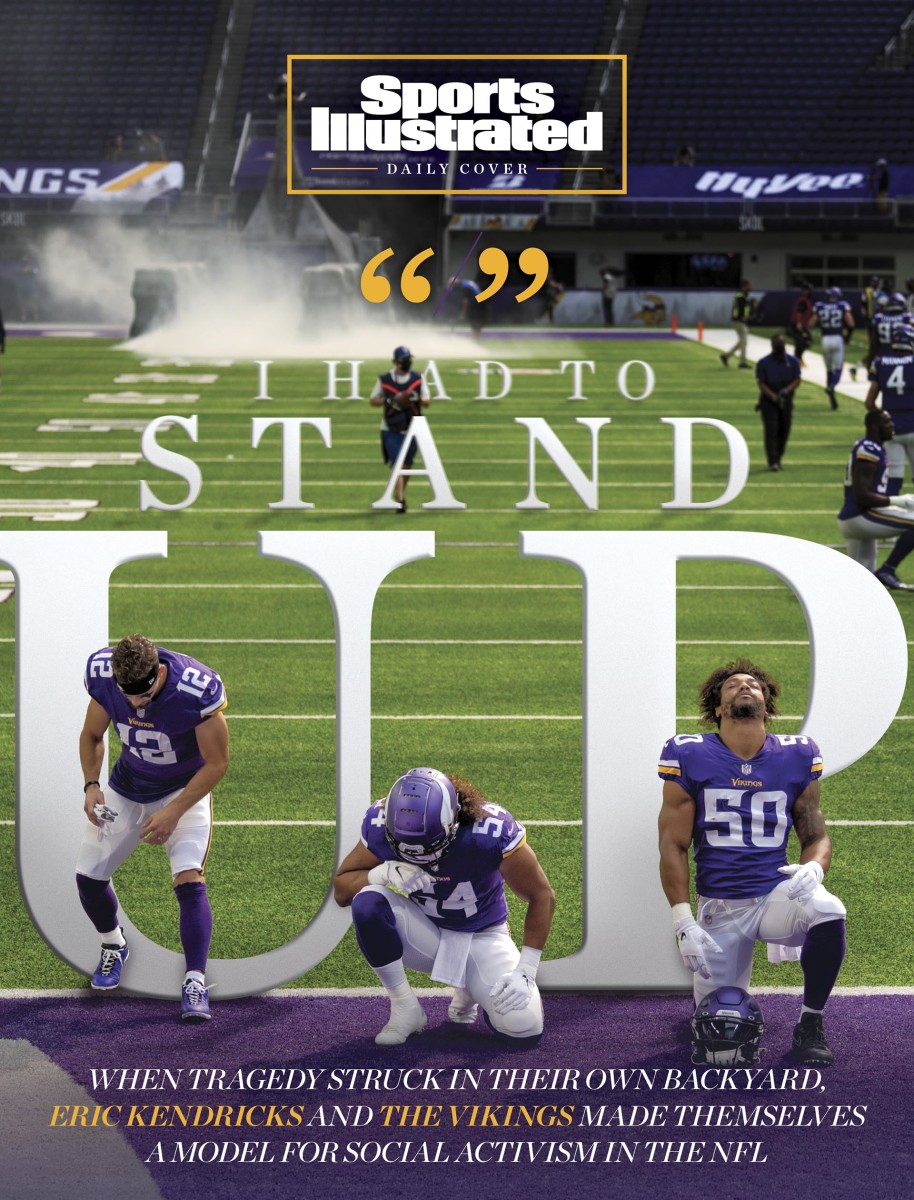

Before the season-opening kickoff, the linebacker found Floyd’s family in the stands, nodded in their direction and smiled at the symbolism. One death had changed so much. For players like him, who sought to prove that modern athletes could balance sports and activism, could be All-Pros and actual people, that the line should be stand up and dribble, because they can do both. And for the Vikings, a franchise that long ago committed to fighting for social justice but now wanted to set the standard for what’s possible in sports. Floyd’s death transformed the conversations about race in the U.S., highlighting the need to do more, be better, seek discomfort and demonstrate and fight racism. All of which informed how Kendricks and the team would approach a year in social justice activism without precedent, as Sports Illustrated followed their pursuits throughout the 2020 season.

After clashing with the Packers that first Sunday, losing 43–34 in a defeat that portended a bumpy start to an uneven season, Kendricks started to understand the dichotomy that would define his fall. “I’m not too particular on being in the spotlight. I never wanted to have a big voice in all this. Really,” he said in the first of several fall phone calls with SI.

“I knew I wanted to do something; I knew we had to. It was eating me up inside. And I knew that with George Floyd happening right here, in our city, I had to stand up.”

Long before the Wilf family owned the Vikings, their ancestors lived in Poland, the country the Nazi regime invaded in 1939, starting World War II. They knew many Jews who were forced into a ghetto starting in ’41, the boundary encircled. The Germans would randomly do roundups, seizing relatives and friends, people they would never see or hear from again. Many of those kidnapped landed in the Belzec death camp; the camp alone accounted for more than 500,000 deaths between March 1942 and June 1943.

Desperate, Elizabeth “Suzie” Fisch turned to her mother, Miriam, who hatched an escape plan for the family’s surviving members. She obtained papers from the Jewish militia that distinguished her, should the Germans ever ask, as a Christian woman with two Christian children. After a local farm hired her, she rode out the war there, hiding her husband, even from the farm’s operators, under floorboards in the barn. “Out of 180,000 Jewish people living in Lvov, they were part of just a handful to survive,” says Mark Wilf, who now owns the Vikings with his brother, Zygi, and cousin Leonard. (Suzie is Mark and Zygi’s mother and Miriam their grandmother; neither would be alive if not for the family ethos of resourcefulness.)

After the war ended violent outbreaks against Jewish citizens continued, leading the Wilfs to move to an American-occupied zone in Germany. There, Suzie met Joseph Wilf, eventually discovering that he had been forced into a Siberian labor camp, along with his parents and his older brother, Harry. They emigrated to the United States in 1950. Joseph and Harry would become real estate development magnates in New Jersey, bank generational wealth and start the Wilf Family Foundations, donating over $200 million to the Jewish community over 50 years.

That history deeply informed the Vikings’ response to the controversy generated by Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the national anthem in 2016, his chosen way to protest police brutality and economic inequality. President Donald Trump inflamed his base by mischaracterizing the quarterback’s stance the next year, while the majority of other NFL owners, decision-makers and the league itself largely remained silent. Worse, prominent figures like Jerry Jones told players they must stand.

Children of immigrants who could empathize with the Black community took the opposite approach. They formed a social justice committee of players, coaches and team employees in ’17, four years before that became a popular response throughout sports. They hoped to strengthen dialogue, improve systems and infrastructure, and become a prominent ally to programs and activists. They organized team meetings to hear from players who told stories of pervasive traffic stops and incarcerated relatives, who had played football games as gunshots echoed nearby but also knew the dangers police officers confronted every time they clocked in for a shift. The Wilfs shared their family history in return.

Then, the Vikings execs did something unusual: listened to their players. They began working with organizations that tackled these issues, from a juvenile detention center to groups focused on education in low-income neighborhoods to African-American history museums.

Players didn’t eye the committee with suspicion, but they studied it, nonetheless. They believed that the Wilfs could relate to their experiences and intended to help. But they also knew how charity efforts tended to unfold in professional sports, on more of a surface level, with positive publicity always a goal, if not the goal. “You welcome it, but you want to see how it plays out,” says linebacker Anthony Barr. “Like, is this just something that they’re doing to save face and look good on the outside? Or is this something where they are really going to try and use this platform to create a substantial and sustainable change?”

The social justice committee the Wilfs created met again this past September, after the Floyd protests had sparked conversations across the league. Kendricks and Barr and other heavily involved players—Ameer Abdullah, Alexander Mattison, Anthony Harris—joined the virtual discussion, their exchange similar to conversations that took place in ’17 but different in important ways: more total players and more white players, too.

Many of these Vikings had flown to Minneapolis after Floyd’s death, to meet with the police chief, each other and various programs, donning activist hats rather than athlete ones. They already knew the issues, the stakes and their allies. People like Andre Patterson, the team’s co–defensive coordinator who had grown up in poverty and served as a sort of liaison between the locker room and the higher-ups. And Rick Spielman, the general manager who adopted six Black children with his wife, Michele—both saw firsthand how officers treated them. Like when police pulled over one son for driving Michele’s car, only to turn friendly once Vikings general manager became established. Or when police pulled the same son and friends out of a restaurant, citing a robbery nearby—only because, Spielman says, “they automatically thought it was them.”

On this particular call, the GM, the co-DC, Kendricks and his teammates continued mapping out a plan to move forward, using their own backgrounds to guide their choices. The Wilfs had pledged $5 million to social justice efforts after Floyd’s death—on top of a $500,000 commitment in the two previous years for school supplies, legal aid for disadvantaged populations and police-community relations. Just like with the $500K, they were putting players in charge of dispersing $1 million of the total. Their collective aims had crystallized into three areas of focus: voter education and registration, educational curriculum on racism and Black history, and law enforcement and criminal justice reform.

The committee debated which organizations to give money to, discussed how to maximize online meetings with incarcerated youth and learned details about the scholarship endowment the franchise had created in Floyd’s name. They wanted every person in the organization to register to vote by the presidential election in November.

As the linebacker listened, Kendricks couldn’t help but think how much had changed since Kaepernick first knelt. He had always considered the quarterback’s stance and sacrifice brave, but back then, he kept his own social justice efforts more private, lest anyone think he sought attention. Now, he could do anything, and he needed to do more, go deeper. “We can wear T-shirts, talk about these issues,” Kendricks says. “But we need to create real, sustainable change.”

The linebacker criticized the NFL’s initial response to Floyd’s death. He participated in a widely shared video featuring pro football stars calling for the league to do better and more. He went with teammates to meet Medaria Arradondo, the chief of the Minneapolis Police Department, a Black man who spoke openly about the problems inherent in the criminal justice system and the longstanding issues his department continued to confront. Arradondo told stories of officers fired for transgressions, only to be brought back behind heavy pressure from powerful police unions.

It felt like progress, at least until Aug. 23 when another Black man, Jacob Blake, was shot by a police officer in Wisconsin, the tragedy providing renewed motivation. The Vikings watched NBA and WNBA players pause their bubble schedules in response, sparking would we? conversations in NFL locker rooms. Kendricks did not rule out similar action, although he hoped he’d never have to make that choice, meaning he hoped against logic that frayed racial tensions would improve. As for those who questioned his capacity to be both one of the best players in the league and an actual human being striving to impact the wider world, he could only laugh.

The season nosedived—from the start, really—as the free-falling Vikings didn’t register their first win until Week 4 against the staggering Texans. Minnesota lost five of its first six games before the bye week, dropping a late lead at Seattle and enduring a beating from Atlanta before the Falcons fired their head coach. COVID-19 continued to rage across the U.S. The homestands continued to sit empty, sterilized, silent.

Kendricks, meanwhile, continued his stellar play, registering double-digit tackles most weeks. Despite, he says, feeling increasingly overwhelmed. Floyd’s death, the proximity, the protests and demonstrations, the social justice efforts, the pandemic restrictions, the close defeats, the blowout ones, even the death of his beloved French Bulldog, just 3 years old—“just a lot of stress,” he says in October, his season already thisclose to collapse.

In previous years, Kendricks believes he would have forced himself to push forward, trying to do everything, be everything, only to worsen the mental exhaustion that made each day more difficult in an already grim year. This time, he needed to step back. Really dig into his emotions. Talk through the anxiety with those closest to him. Realize that one person could “only do so much” and he couldn’t change the entire world in a week, month or season. By recharging, he would steel himself for the longer fight ahead. The one that would last his lifetime.

As the bye week began on Oct. 19, the Vikings trailed the NFC North–leading Bears by four games. Players continued to encourage each other, despite their dire reality, pointing to close losses, strengthened bonds, practices that showed them alone what they were capable of. Take chances, Kendricks told teammates. Be confident in each other. In some ways, he was talking to himself, trying to find the balance he used to navigate the early portion of the season. “We’re a good team,” he insisted. “It’s important that we believe that, too.”

Jeremy Wright saw a decade ago, at Hoover High in Fresno, Calif., what strangers would later miss in Eric Kendricks. The 10th-grader with those curly black locks always wore flip flops into modern world history class and made jokes about his teacher’s flip phone. But the looseness served as a kind of shield from the impact the teen not only would make but always aspired to.

Kendricks took AP Government two years later, deepening his relationship with Mr. Wright, unspooling his family story one tidbit at a time. Like: his mom, Yvonne Thagon, who tirelessly worked the graveyard shift at a pharmacy to provide for Eric and his siblings … the relatives who helped with child care and food … and the family friend known as Uncle John, a California Highway patrolman who was once shot in the leg in the line of duty. Eric sent letter after letter to the hospital bed, until Uncle John recovered, the bullet underscoring the peril baked into the job description.

The athlete and his friends had also been profiled by police in the same city. One time, according to Kendricks’ recollection, a gang unit stopped them, yelling about the car running a stoplight when “we weren’t doing anything wrong.” The vehicles pulled into a gas station. The cops pulled their guns and shined flashlights in their faces, shouting for the students to show them their tattoos. Eventually, one spied the linebacker’s letterman’s jacket—and off the kids went, without a ticket, but with a personal lesson in why their community often viewed officers with suspicion.

Use your powers for good, Wright wrote in Kendricks’s yearbook, offering his cellphone number.

The teacher never expected the linebacker to keep in touch, but Kendricks did. Still does, in fact. Wright helped him shift his focus from a degree in economics to majoring in political science at UCLA. Kendricks helped Wright by speaking to the football team, the golf team and a multicultural assembly.

He also carried Wright’s lessons and his poli-sci studies into the NFL, visiting those juvenile detention centers, trying to help children like the ones he knew in Fresno. Good kids, he says, who needed structure, activity, guidance. Those visits led to further study on incarceration rates and related costs. That led to a dive on the performance of students relative to whether the school provided breakfast for them. To make the change he wanted, he began to realize, he needed to know more, about laws and systems and the organizations created to make them better.

Mr. Wright noticed the advancement, especially in 2020, when he watched the video Kendricks filmed after Floyd died. The teacher ran to show his children, ages 16 and 13. He pointed to an evolution on the screen, to the student who always planned to make a difference but didn’t know how or how much until recently. Wright believes it took Kendricks “a while to find his voice because of what happened to Kaepernick.” More important? He did find it. Tears rolled down the teacher’s cheeks, reminding him of a message long ago scribbled into a dusty yearbook.

Use your powers for good.

The Vikings’ social justice work helped Minnesota again lead the nation in voter turnout percentage. Nearly every employee registered. Kendricks, after taking the break he needed, began focusing on All Square, a local nonprofit founded by a civil rights lawyer, Emily Hunt Turner. The organization invests in formerly incarcerated people with leadership potential through a 12-month fellowship anchored in mental health, wealth and entrepreneurship, and much of the fellowship takes place through a restaurant attempting to forge criminal justice reform one artisan grilled cheese sandwich sale at a time.

The team partnered with All Square, and in 2019 Kendricks started dropping by for sandwiches, sometimes with teammates, sometimes alone but always in pursuit of deep, meaningful conversation. Turner loved the Vikings’ support and hated how the NFL had treated Kaepernick. She also long ago familiarized with “situations where folks of some notoriety helicopter in for a photoshoot and bounce.” She wanted the kind of profound relationship that Kendricks appeared intent on developing, and she found him approachable, engaged, authentic. “There was a sincerity about him,” she says, “a rare spirit.”

One afternoon after Floyd’s death, they all sat outside the restaurant in a giant circle, these Pro Bowlers and lawyers and the formerly incarcerated fellows who continued to share the injustices they have experienced. For some of the players, this marked their introduction into the barriers present upon release from prison.

That same night, Randall Smith told the Vikings about his life and how he changed it. The prison stint. His deep look at institutional racism. The son whose birth forced him to make better decisions. The systems that made it difficult for him to find work, before he met Turner. The idea he brought to her, to establish a fund in Floyd’s name that would be distributed to employees with entrepreneurial ideas, so they could start their own businesses. All that countered by the police officers who have always followed him, who still do.

On the night that Floyd died, Smith toiled in his buddy’s detailing shop, just down the street from the now-infamous intersection. He wondered why crowds had started to gather, why police blocked off the road, why everyone seemed as angry as he would feel the moment he found out.

“We got harassed at that same area,” Smith told the assembled Vikings. “I see it all the time. I could be anywhere, and the police see me, and it’s not even like they’re trying to identify what happened. It’s, I’m keeping my eye on you, motherf-----. ”

Kendricks and Barr would pull Smith aside, saying his story had motivated them to help him inspire change. The social justice committee would award the All Square Fellow Fund a quarter of the $1 million allotted for the players to disperse. Kendricks would present Smith the check, Publishers Clearing House–sweepstakes style, because the money would, in part, fund his idea. Smith now knew he could open the mobile detailing clinic he had developed. “Are you serious?” is all he stammered.

The same day, Smith says police pulled him over and harassed him for the fourth time that month. He estimates that cops have pulled him over more than 100 times. He called 9-1-1, as backup arrived, screaming to the operator to “make them stop.” He knew that might put his life at further risk, but wanted someone, anyone, to hear him.

In a blog post, Smith wrote about the two realities he faces every day, that one especially: the promise of his future and the possibility of his death. What Smith can’t figure out is how a police force ostensibly tasked to protect the community seems to find him threatening, while a football team that exists to entertain the masses views him as a leader, worthy of investment. What did that say, he wondered, about Eric Kendricks, the Vikings and the world?

The team elevated its on-field play after the bye, with Kendricks, the defensive leader, cajoling a young and reconfigured unit to meld together as the season of balance found and lost and found again continued to fly by. Minnesota topped two division rivals, Green Bay and Detroit, before a Nov. 16 game against the Bears. On the morning of that pivotal matchup, an injured Barr considered the events of the previous five months and how they changed his close friend and fellow ’backer. He was proud of Kendricks, a teammate who lived on the “quieter side” but became more vocal at the precise moment that he needed to step forward. “You’re getting the uncensored version, where the guard comes off, and you’re getting raw emotion and reaction from him,” Barr says.

Minnesota proceeded to climb back into the playoff picture, beating Chicago, Carolina and Jacksonville—with a loss to Dallas sandwiched in there. That the victories all came in close games spoke to a roster fortified by more than football, Kendricks says more than once. The learning continued, as did the empathy and the Zoom calls and a growing sense that their work this season could become a blueprint for other teams and built upon in the years ahead.

People like Alan Page, the franchise’s Hall of Fame defensive tackle who left football and became an associate justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, noticed. The team had long supported his Page Education foundation. But in 2020, he says the Vikings’ impact on the outside world has never been stronger, more necessary or more involved, the efforts bolstered by its ownership, its general manager, its co–defensive coordinator and the linebacker whose voice was now coming through a megaphone. “That’s the way you hope it works,” Page says. “We all have some power. It’s a question of what we do with that power. Some of us don’t use it at all, some of us neglect it. Others use it in ways that aren’t as productive as they could be.

“The Minnesota Vikings use that [power] globally.”

The social justice committee in Minnesota held its latest meeting on Dec. 8. This call took place after the Jags win evened the team’s record at 6–6 but before a loss to Tampa Bay pushed the Vikings back on to the playoff fringe. Kendricks missed both games with an injured left calf—he did not practice Thursday and will likely miss this Sunday’s game but hopes to return this season—losing the balance he sought but in an it’s football way. He still jumped on Zoom, where dozens of screens combined for a Midwest football version of Hollywood Squares, as city lights glimmered in some backgrounds and white walls dominated others.

Team employees kicked off the call with a recap: $910,000 of the $1 million had been distributed over the course of the season to 19 organizations, with the grants ranging from $5,000 to $250K. The money went to street artists, school supplies, students, scholarships, the grilled cheese aficionados and Page’s education group. Players offered suggestions for the remaining 90 grand, recommending organizations that advocate for abused women, or single mothers, or foster children. Zygi Wilf addressed the future, telling the players that “we’re committed to doing this long-term” and “social justice is a lifetime commitment.”

Eventually, Spielman asked Kendricks whether he believed the organization was helping in every possible way. The linebacker sat in front of white brick walls, nearby what appeared to be a roaring fireplace. “I feel good,” he said in response. “I’m learning more every day.”

Sometimes, throughout this fall, Kendricks would look back at old pictures of a home stadium packed with fans, nobody wearing masks, back when George Floyd was still alive, Trump had not yet lost his reelection bid and Kendricks’s own public profile still remained largely in the background—his choice. To the list of things that changed in 2020, he would add: himself. He felt blessed to play this season, even in those times that stretched him, despite the late injury and the losses. He hoped to carry the balance he found into other seasons. “I wanted to make sure that if I did something [like this] it was authentic to my core,” he says. “Then I realized that I’ve gotta stop worrying about everyone else. Now, I feel like I’m functioning at my highest when I’m doing as much as I can.”

The AP Government teacher wonders whether his pupil will run the NFL Players Association one day. The general manager who grades Kendricks on the field hopes that day isn’t all that soon. The Vikings nominated Kendricks as their Walter Payton Man of the Year that same week in December, but none of these sentiments came up on the Zoom call.

Instead, Patterson, the co-DC, told the Vikings he needed them to know “that your touch has been felt” and not just in Minnesota. “Because [it has] been a crazy year, and you guys haven’t been able to get out in the community like you normally do, I don’t want you to think you didn’t reach people in the way that you normally do. The time and effort that you put in … shows you’re human. I’m proud as hell of you.”

Kendricks, though? He used this particular call to highlight developments at All Square, the plans for future growth. The civil rights law firm soon to be added to the grilled cheese spot. The focus on impact litigation and ensuring that penalties for crimes are shaped, in part, by those who have experienced legal disparities.

There’s a chain reaction that Kendricks sees here, the way that each action builds on the one before, until they’re all working together, as small changes grow into bigger ones. Like:

The Vikings' interest in All Square …

His desire to make real connections with the sandwich artists …

The franchise’s response to Floyd’s death …

The Wilfs’ investment …

Smith’s idea for the fund …

The grant earmarked by the social justice committee …

Followed by the lives that the influx of cash changes …

The formerly incarcerated fellows with economic freedom created by the businesses they can start …

Their newfound ability to help others coming out of prison, with jobs and resources …

As the cycle continues to repeat.