How—and Why—the Senior Bowl Is Happening

There was a single player who didn’t make it here on time, having missed his flight, and as Saturday morning turned to afternoon, and COVID-19 tests were taken and processed, Senior Bowl executive director Jim Nagy was inching closer to having as a good a start as he possibly could have hoped for to what promised to be a challenging and hopefully one-time-only sort of game week.

One-hundred and thirty-six players were invited to Alabama’s Gulf Coast and confirmed for what’s annually the nation’s premier college all-star game. When Nagy went to bed Saturday night, he was 135 for 135 on players testing negative. When Nagy woke up Sunday morning, the bad news came: No. 136 was positive.

“And I’m going, nooooo,” Nagy said Tuesday night. “We almost did it.”

Nagy jumped on the phone and sent some medical people up to reswab Player 136’s nose, and then directed him to isolate in his room for the time being. For the guy who’s been in the center of this balancing act—trying to get an all-star game played while mitigating myriad risks tied to a pandemic—and the player in question, and for his agent, too, peppering Nagy with texts, the hours to follow felt like days.

Which is just what led to the exaltation when the results returned.

False positive.

“We had to send someone over to get him out of his room, get him back over to the Renaissance Hotel, and to see the guy with a smile on his face ...” Nagy said, trailing off. “He’s a small-school guy. I’ll leave it at that. So he really, really needs this week. ... He gets it ripped away from him as soon as he gets here, and then he gets it back. I’ll never forget the look on his face when he came to the hotel to show up that day.”

So began the week for the highest-profile all-star game in North American sports since the pandemic shut our country down 10 months ago, a week of practice to be followed by the game itself on Jan. 30. Neither Nagy nor anyone else was out of the woods at that point. They still aren’t. But that didn’t take away from the emotion, after all that went into putting the game on this, of that one little win in what everybody here is hoping will finish as a week full of them.

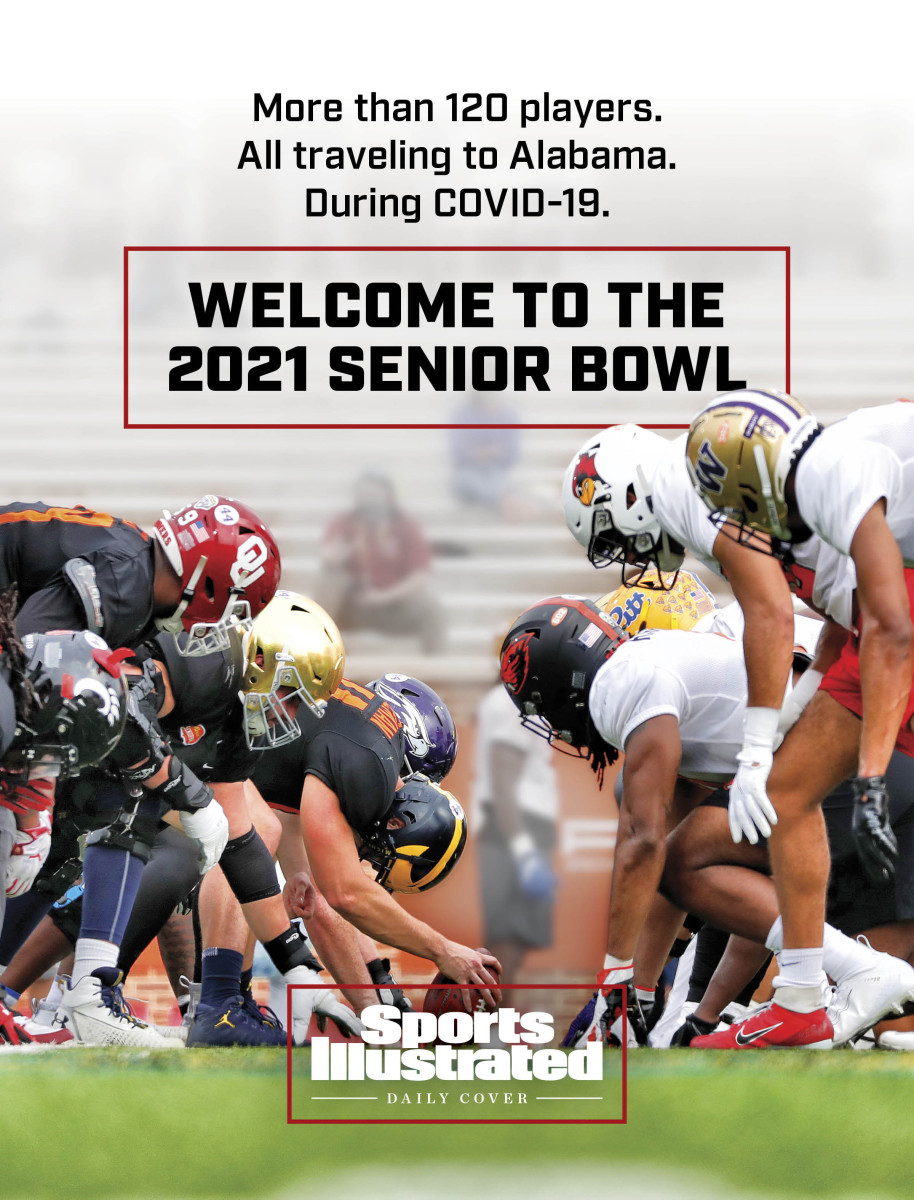

Midway through Tuesday’s lunchtime practice for the National team, Notre Dame quarterback Ian Book called for a huddle that had receivers from South Dakota State, Arizona State, Notre Dame and Western Michigan and a tailback from North Carolina. They took three snaps, and then in came Texas quarterback Sam Ehlinger, with receivers from Wake Forest and Louisville, a slotback from UCLA, a tight end from Ole Miss and a tailback from Virginia Tech. Directing them were the offensive coaches from the Dolphins.

Therein lies how different this is than playing an NFL game or a college football game. There’s a reason why all-star games have been called off—mostly because this isn’t the time to be flying people from every corner of the country into one location and putting them all in a hotel together.

The NFL people who’ve worked on COVID-19 have a saying for the risk of these sorts of gatherings. It’s like throwing a match into a dry haystack. It’s why the NHL and MLB canceled their all-star games, why the NBA is considering ditching theirs and why the NFL has canceled anything resembling the scouting combine, replacing it with pieced-together fragments that they hope will reasonably approximate the normal doing of draft business. Why did Nagy see the need to go forward where others haven’t?

Well, for one, this isn’t so much an all-star exhibition as it is an all-star showcase—a job interview for the players and a chance for NFL evaluators to see guys physically, informing million-dollar decisions they’ll make three months from now. And two, with the centralized combine off, there was even more of a need for the Senior Bowl in 2021.

Nagy, a former scout for the Patriots, Chiefs, Seahawks and Washington, says that player safety was the top priority. But he adds: “I think what’s lost on a lot of people was the fact that these [NFL team] decision-makers weren’t seeing players this fall. There were a lot of scouts out at colleges this year. I ran into a bunch of them down here in the Southeast. … But the guys that are making the decisions in April, they weren’t at games. They travel with their teams in the fall. So you couldn’t go to a college game on a Saturday, reenter the bubble with your team on a Sunday and go to the game. The one GM I spoke to that did go to college games, he had to quarantine well into next week.

“This week, for the vast majority of these [decision-makers], this will be the first time laying their eyeballs on players.”

Getting here wasn’t easy. The process, for Nagy, started all the way back in March and April. It had become clear that the pandemic was going to last well beyond a few weeks, but at the time Nagy was like a lot of people: While he was concerned enough that he and his staff started on contingency plans, the idea that COVID-19 would last into 2021 was hard to fathom.

Nagy was in constant communication with NFL general managers and college head coaches, and being right down the road from the University of South Alabama, which played an 11-game football schedule in the fall, gave him the chance to observe and really “get really in the weeds” with the program and what AD Joel Erdmann was dealing with.

The overriding advice? To avoid “big congregations of people. I think someone said [don’t] meet, eat and greet.” And that wound up informing a lot of the Senior Bowl’s rules.

The starting point was a virtual bubble. The players and coaching staffs working the game had to go through three phases of testing to enter—bringing a negative PCR test with them to Mobile, arriving in Mobile on Saturday to take another PCR test then stay in an off-site hotel and, finally, taking a rapid test Sunday to gain entry into the downtown Renaissance Hotel and Hampton Inn designated as the bubble.

For the 30 teams not participating in the game, attendance was limited to 10 per club, meaning a great majority of coaching staffs were not in attendance (the Giants and Bengals were outliers in that regard).

Once the players got in the bubble, distancing and masks during meetings were mandated, with each coach (from the head coaches to position coaches) given the option to make their meetings virtual. Meals were grab and go.

Some of the chaos of years past was managed down. Interviews were no longer a rush to grab guys when you could—they were scheduled out for 15 minutes apiece in pods assigned to the teams at the convention center, with plexiglass separating interviewer and interviewee. (Some evaluators were unfazed, comparing it to talking to a bank teller.) And in the past, teams would send young scouts to the all-important weigh-in at the crack of dawn to save seats in the first couple of rows, with tempers occasionally flaring between the early risers. This year, the seats were assigned and spaced. Some of the changes worked so well, they might not go away.

“The weigh-in part was really smooth this year,” Nagy says. “Those poor scouting assistants, even at the combine, same deal, some teams will have those guys go over there at 3 in the morning and sleep out in front of the weigh-in area. It’s ridiculous. Another part we would really like to think about continuing on in future years is the interview format. I went over there last night, it was the first night of formal interviews. And just had that immediate feedback from those guys, it was really working.”

The changes led the first part of the week to go smoothly, but none of it was cheap. Nagy says he spent $12,000 on plexiglass alone, and that’s just one example of costs popping up to facilitate the game that didn’t exist before. Players were singled up, rather than doubled in hotel rooms. Getting through the week required buying up thousands of tests. And the fan events associated with the game were eliminated, with stadium attendance cut way down.

Nagy said if he revealed the cost overruns, “I think our treasurer would probably get me in a headlock. Needless to say, it’s significantly more than a normal Senior Bowl year. We’ll see where the financials end up. But again, we wanted to make this happen.”

And the Senior Bowl knew the teams wanted it just as bad as they did, which led to Nagy & Co. asking for partnership for them. This year, for the first time, the 32 teams had to buy into the game, and they were offered upgraded packages that included a suite at the stadium, with catered meals and flat-screen TVs to watch coverage of practice on.

All 16 suites sold, putting more than half the 30 noncoaching teams in them. And sure enough, when a steady rain passed through Tuesday, guys in the suites playfully pointed down and laughed at the guys in the seating bowl who were scurrying for the concourse.

Beyond NFL teams chipping in, Nagy also asked for help from the Senior Bowl’s sponsors, who stepped up.

So who are the potential long-term beneficiaries of that effort? Really, it’s all the players and teams. But more than anyone else, it’s the Panthers and Dolphins, who, because they’re coaching in the game, brought traveling parties of around 60. In a year when any sort of personal interaction with the draft prospects is going to be at a premium, Carolina and Miami will have been in meetings and at practice with nearly 70 of them each.

Conversely, one NFC executive said to me that “the idea my head coach isn’t going to be face-to-face with any one of these guys before the draft is unfathomable.”

That’s why, when Panthers coach Matt Rhule went to his staff with the idea of coaching in Mobile, despite a draining first year in Charlotte, the guys were on board.

“We’re still building a roster,” Carolina defensive coordinator Phil Snow said over the phone Wednesday. “It’s important at every position that we evaluate properly for this draft and the following draft. ... We talked about it, said, ‘Hey, let’s go do this thing.’ ”

Not every staff was willing. Every year, the Senior Bowl invites coaching staffs in order of their slotted spots in the draft order, excluding teams with new staffs. Carolina is slotted eighth and Miami 18th, meaning Nagy & Co. got a lot of no’s before they landed on a second yes.

Why was it difficult? In large part because this year, in particular, was a long one, and a lot of head coaches wanted to give their assistants time to decompress and reconnect with their families; many told their guys to take off until after the Super Bowl. Conversely, the Panthers staff, still new, saw opportunity.

“We get direct relationships,” Snow says. “We’re working with them in meetings and coaching them, where the other staffs that aren’t working the game, I think they’re further behind. I’ll give you an example—the West Coast didn’t continue to play football, or played three or four games, some of the Pac-12 schools. And then some guys only played two or three games. Some sat out. So we don’t know a lot about these guys like we have in the past.

“Being able to coach in this game is pretty beneficial.”

And that much, too, shows up in simple math. Having six times the number of people on the ground that the other 30 teams do isn’t a bad thing. The Panthers’ traveling party started at 58 (22 coaches, 12 scouting, four training staff, four equipment, four football administration, three football operations, three video, two PR, and one each in IT, wellness, security and strength and conditioning).

The other big winners of the week are the players coming from sub-FBS programs. The great majority of them didn’t play a snap in the fall.

How big a deal is it? Well, agent Ron Slavin predicted that every player here would get drafted because NFL teams, and their primary decision-makers, are going to feel more comfortable with guys they’ve actually laid eyes on.

“I have an FCS and a Division III guy, who didn’t get to play this year,” says Slavin, referencing Illinois State safety Christian Uphoff and Wisconsin-Whitewater offensive lineman Quinn Meinerz. “This is their Super Bowl. And then Carson Green from Texas A&M, they played a full season, he’s beat up from an SEC season, but I said, Look, with no combine happening, going to the Senior Bowl is your best chance. These guys have one more look at you, especially during the one-on-ones and the O-line stuff, that matters.”

That’s made for an interesting dynamic in drills, too. Alabama’s Mac Jones lined up at Wednesday’s American team practice with 13 games under his belt. Behind him in line was Jamie Newman, a former Wake Forest quarterback who transferred to Georgia, then opted out of the season—he last played in a game on Dec. 27, 2019. Which is probably why you heard the prodding from Rhule loudly on the other end of the field with the linemen.

“Either you’re tired or you’re slow or you’re fast,” Rhule yelled. “Be fast!”

“[You see] a big difference,” Snow says. “Guys who haven't played in a year, the timing, everything is off. You’ve got to get back into the flow of it. The guys that did play this year, everything they do is much more detailed and crisp, because they’ve been doing it. All of us, if we don’t practice, we’re not very good. And they haven’t practiced in a year.”

Which, of course, makes how they do on the field even more important in their evaluation. But they’re in an environment that’s less than ideal for performance. There are 5 a.m. wake up calls for COVID testing, and interviews that run until 11 p.m. In between, Senior Bowl practices aren’t like they used to be.

In fact, Florida receiver Trevon Grimes was really looking forward to that part of it—2020 Senior Bowl alums Van Jefferson and Tyrie Cleveland were Gator teammates and told him about a festive practice atmosphere that helped them through the week. This year that is gone, and so Grimes has had to lean back on an old high school trick of his to get himself going.

On the bus over from the hotel to the stadium, he actively “zones out”. No texting. No social media. Just music to get him in position to bring his own energy to the field. As he puts it, through a week critical to his professional future, he’s trying to simplify everything so he’s less worried about all the oddities of this situation. “At the end of the day, when you love something, you get on the field, all that stuff gets blocked out.”

There have been bumps. Carolina offensive coordinator Joe Brady isn’t here due to protocols, as are two other Panthers coaches (knocking the coaching staff number down to 19). And there are still a couple of days to go.

Nagy knows how quickly things can flip. But at this point, he’s pretty proud of the job his team— made up of staffers Dave Rogers, Elizabeth DuPree, Sonya Wakefield and Lauren Fleming, and scouts Matt Kelly, Jeff Ludrow and Tanner Chastain—has done in pulling this off. Because of the risk associated, Nagy says, the closest comp to what they’ve done in flying people in from across the country since COVID-19 hit is the PGA Tour. And those golfers, he notes, travel in private jets.

“The week isn’t over—we need to get there,” Nagy says. “I’m proud of—not even proud, but thankful for the help we received from the NFL. Friends from the 32 teams. The agent community. These players—I'm so thankful for these players, their buy-in to this thing. Some of these guys haven’t had pads on since November of 2019, and they’re coming down here, probably rusty as heck and still getting out here and competing. I just love these guys. Just thankful, grateful.

“Like you said, we need to get to Saturday and kickoff, but no, hopefully we get through the week and can reflect on it, it will be very rewarding. But let’s get to Saturday first.”

Between now and then, there sure could be tense moments like the one Nagy had Sunday, with the week barely off the ground, and that’s O.K. He, and everyone, knew all along that this was going to be hard.

But with a few more of the little victories like he had getting that player cleared to stay, it will be awfully rewarding, too.

POWER RANKINGS

1. Chiefs (16-2): Disregard what I said last week about KC’s most recent margins of victory. It’s not important. Here’s what is: The Chiefs have won 25 of Patrick Mahomes’s last 26 starts at quarterback.

2. Buccaneers (14-5): I wrote plenty about Tom Brady on Monday. Here, I think it’s important to give credit to GM Jason Licht and coach Bruce Arians for the job they’ve done developing young talent. From Mike Evans and Chris Godwin to Donovan Smith and Tristan Wirfs to Devin White and Lavonte David (who, admittedly, was here before the Licht/Arians era), to Sean Murphy-Bunting, Carlton Davis and Antoine Winfield, there’s a boatload of homegrown talent in Tampa that helped set the stage for Brady to bring them over the top.

3. Packers (14-5): There’s plenty of blame to go around, and yes Aaron Rodgers shoulders some of it too. The offseason in Green Bay should be a fascinating one, with Rodgers turning 38 next season.

4. Bills (15-4): I know it doesn’t always work out like this, but there are a lot of good young players on that roster that should continue ascending. It’ll be tough to get back to the conference title game. But the pieces are in place to do it.

5. Browns (12-6): I had them fifth last week, so we can’t really drop them. And the way they hung with the Chiefs does take on a different context with what happened in the AFC title game.

THE BIG QUESTION

What’s the first quarterbacking domino to fall?

I think it’s probably Matthew Stafford, and as a result of that, I think it was smart for the Lions to be aggressive in getting word out there.

The bottom line: We don’t know exactly what San Francisco or Vegas or the Rams are going to do, nor is there true certainty on how the Dolphins and Jets will make use of their Top-3 picks. So if you’re a quarterback-hungry team right now, the Lions are your first call. And with a chance of supply outweighing demand on the quarterback market a month from now, the best idea for a seller is to get ahead of that potential problem.

Detroit has done that, and it’s no surprise that the phone has been ringing, given the regard that Stafford is held in across the football world. And there’s precedent for making a deal this early in the process—recent history at that.

I remember this because the news dropped during the media party at Super Bowl LII in Minnesota, and we were all at the amusement park in the middle of the Mall of America (which reminds me of how bizarre that Super Bowl was, with so much of the action happening in a mall in suburban Minneapolis in January/February). The date was actually Jan. 30, five days before the big game, with Washington agreeing to acquire Smith for Kendall Fuller and a third-round pick.

The one caveat there was the deal could not be made official until the start of the new league year, six weeks later, which left both teams free to back out. But neither did, and the deal was done, and it set off a ripple that wound up entrenching Patrick Mahomes as starter in Kansas City early in his first full offseason as a pro, and (finally) spelling the end for Kirk Cousins in Washington. Cousins went to the Vikings, which push Case Keenum to Denver.

And I really think it’s the sort of thing that benefits everyone. The Lions get to maximize Stafford’s value, and start planning forward. Stafford’s new team gets the proverbial bird-in-the-hand, and can start looking ahead to free agency knowing what it’s building around. Stafford, meanwhile, gets to move on early, and maybe even have a hand in how his new team shapes its offseason.

WHAT NO ONE IS TALKING ABOUT

… That the 2021 draft’s receiver crop could be better than last year’s.

Nagy said it to me on my podcast the other day, which prompted me to start digging into it, and I think he might be right on this. The best receivers in the 2021 class really aren’t participating here in Mobile. Alabama Heisman winner DeVonta Smith is here, but isn’t doing so much as weighing in as he rehabs his dislocated finger. LSU’s JaMarr Chase, Bama’s Jaylen Waddle and Minnesota’s Rashod Bateman aren’t here.

And even with those top guys not in play at this particular all-star game, the receivers are still all the rage. In fact …

• Everyone seems fascinated with Florida’s Kadarius Toney, who’s flashed top-end movement skills. He had a stellar Tuesday. Wednesday wasn’t as good (two drops, a fumble), but it’s not hard to see there is a lot to work with there.

• Oklahoma State’s Tylan Wallace has looked smooth and natural as a route-runner, proving a tough cover for whoever’s on him.

• Western Michigan’s D’Wayne Eskridge’s name is on the tip of everyone’s tongue, a big-play-waiting-to-happen type.

• Clemson’s Amari Rodgers, a hyper productive (if a little small) collegian, showed signs his game could translate to the NFL in a Sterling Shepard kind of way.

Add it up and what you have is a strong-at-the-top and deep group that could challenge the historic marks that last year’s group of receivers set. It should be fun to watch, and I wouldn’t expect this trend to slow either—with where the game is going stylistically, and how 7-on-7 ball continues to grow at the lower levels of football, the best athletes are playing receiver and being given a ton of avenues to develop at the position before getting to this stage.

THE FINAL WORD

Super Bowl week’s coming, and this will be a different one. The Bucs, of course, are playing a home game. And the Chiefs will arrive in Florida on Saturday, one day before the game.

Throw in the fact that the stadium won’t be near capacity, and this going to be a very different week leading up to the biggest single game in sports. We’ll detail more on that in the Monday column.