Magnificent Seventh: How Brady’s Bucs Became Super Bowl Champions

By the last day of November, the Buccaneers’ grand football experiment was tilting closer and closer to failure. The Bucs—who had taken a young, talented roster and added the most accomplished quarterback of all time, albeit near the end of his career—had dropped three out of their last four, sputtering on offense in a Monday-night loss to the Rams, then falling to the favorites from Kansas City. Both defeats took place at Raymond James Stadium, the future site of Super Bowl LV.

Tampa Bay trudged into its bye week later than usual, 12 weeks into the strangest of seasons. Beyond the pandemic, racial unrest and a country divided—all the serious issues—there were football matters to contend with, a season to be saved.

The two figures who most controlled the team’s fortunes decided to meet, same as they did every week throughout the season. Only this meeting was longer and more important, the kind of summit that could change narratives, legacies and NFL history. One way or another.

* *

So Bruce Arians, pro football’s third-oldest coach, and Tom Brady, the league’s most senior QB, scheduled a round at Old Memorial Golf Club. Naturally. But when NFL officials nixed an in-person meeting, the duo adjusted, same as they would throughout this tempestuous season. They hopped on an old-fashioned phone call instead.

The conference lasted over an hour. Both coach and quarterback spoke honestly, aware of the immense stakes. Arians sought to learn which schematic concepts Brady wanted emphasized, and how he could tweak their offense to peak over the final four games. “I wanted him to be going down the stretch as comfortable as possible, because we had to win every game,” says Arians. “[It was] a melding of the minds.”

At one point, he told Brady, “If you don’t like it, we’re throwing it out.”

The gap that needed closing centered around two long-held and long-successful offensive philosophies. Arians tended to call plays by embracing the risks involved, while Brady preferred stabbing defenses over and over for a slow bleed. The experiment was still in the incubator stage, even three months in. New teammates, new coaches, new play calls, new timing. Even Brady’s progressions varied from his two decades in New England.

Coach and quarterback never added a third party to that phone call, but they still managed to hit the merge button. Ultimately, they settled on a compromise, each bending to accommodate the other. Soon after Brady hung up, he told confidants he had a “great talk with B.A.” and “we’re going to get things going in the right direction.”

At that point—with all the novelty, the lack of practice reps, the virtual meetings, no preseason—Arians admits he wasn’t yet thinking about a Super Bowl. “This season,” he says, “was gonna be ‘Let’s all get together and on the same page and win it next year.’ ” The call, though, followed by a 17-point comeback win in Atlanta, he says, “kick-started the rest of our season.”

Flash forward. Sunday night. The same Raymond James Stadium. Super Bowl LV against the Chiefs and one Patrick Mahomes, the quarterback vying to replace Brady atop the NFL universe. There was a coach, at 68, old enough to have already been vaccinated for COVID-19, and a QB to remind the world that, for him, there’s no such thing as old. There were the Bucs, their mighty defense, their tweaked offense. And there was, despite a season defined by newness, the most familiar sight in modern football: Tom Brady, raising the Lombardi Trophy with both hands after a 31–9 victory. He and Arians became the oldest player and oldest coach to win a championship, Brady’s seventh, more than any single NFL franchise has collected. This became a separator, the one that answered, for now, just what a 43-year-old could accomplish after leaving New England.

Arians sensed this the week before the Super Bowl. “Tom is playing for his teammates right now,” he told Sports Illustrated. “He wants those guys to experience what he’s experienced six times. I think personally, too, he’s making a statement. You know? It wasn’t all coach [Bill] Belichick.”

Months before the meeting that saved the season, only a handful of people knew that Brady faced the kind of fear he never encountered on a football field. On every drive to and from his new office, he FaceTimed with his dad, Tom Brady Sr., who had been hospitalized with COVID-19. “It was life or death,” the father says. “They didn’t know if I’d make it or not.”

Both of the quarterback’s parents tested positive. But Brady’s mother, Galynn, who underwent chemotherapy treatments for breast cancer during the 2016 season, developed more mild symptoms. Senior could hardly talk, lift his head or concentrate for more than a few minutes. He spent most of September in a California hospital. And, after three decades of attending most of his son’s games in person—or at least watching on TV—he missed both a loss to New Orleans in the opener and his son’s first win in another uniform, over Carolina in Week 2. “I didn’t even care if there was a game,” Brady Sr. says. “I was having 100% oxygen pumped into my body.”

That meant lying on his stomach, which made it easier for his lungs to absorb the oxygen but also impossible to sleep. Nurses began to mention ventilators, which only scared the family more. Fortunately, Brady Sr. left the hospital in late September, eventually returning to what he calls “better health.”

Still, this marked yet another obstacle to confront, continuing an often-overlooked pattern embedded in Brady’s Super success. He hasn’t just won and lost an unprecedented number of championship games. He has won and lost Super Bowls while supplanting an injured starter and returning from a serious knee injury, through real scandals (Spygate) and dumb ones (Deflategate), and with both parents in poor health. “The general fan thinks he just puts on his cape,” his father says.

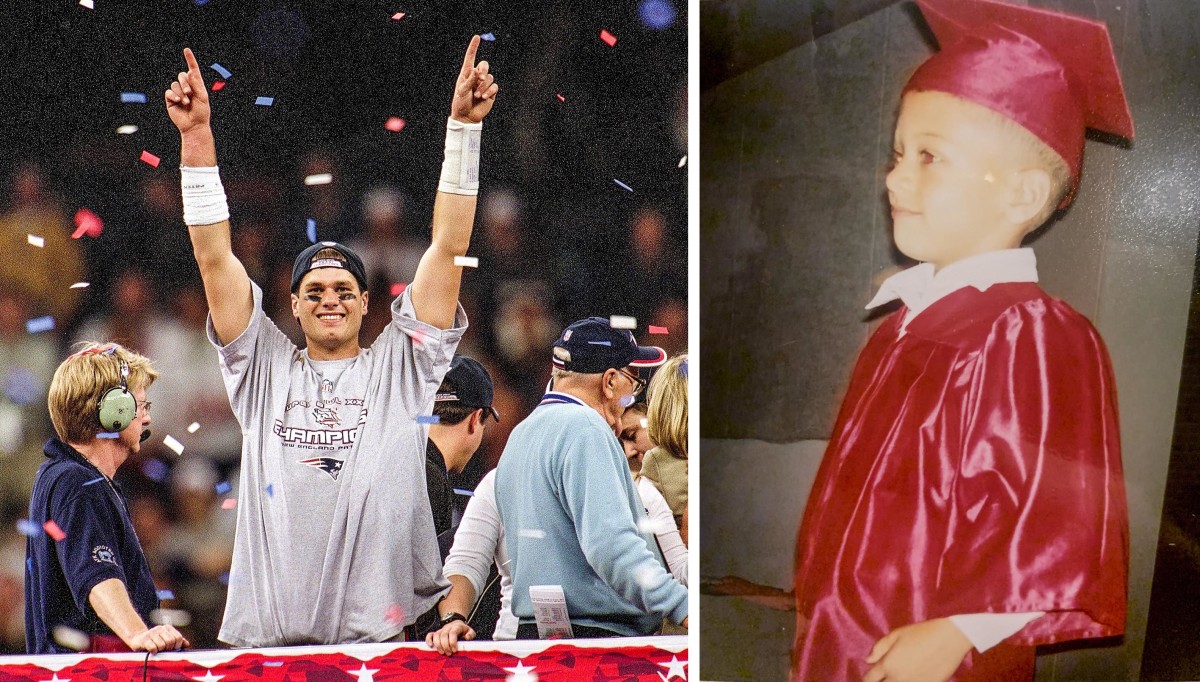

Instead, to win that often, to make reaching the Super Bowl appear this easy, only adds to the never-again nature of Brady’s reign. His father can still recall the first title. New England and its new starter faced the St. Louis Rams—before the move to L.A.—in 2002, in New Orleans. Super Bowl XXXVI. Those Patriots, Brady Sr. remembers, had stumbled to a 5-5 record, before running off eight straight victories to reach the championship. Their previous loss had come against the same Rams.

When his son did triumph, Brady Sr. briefly left the team party, at 4 a.m., to spark a cigar outside in the French Quarter. As he puffed, he wondered if life could ever get any better, a sentiment that’s hilarious in hindsight, because it did. It is. That same night, his son stopped by Belichick’s hotel room and asked if he could fly to Disney World for the typical MVP ceremony. “Geez, of course,” the coach responded.

In the glorious aftermath, Brady Sr. flew to Boston for a visit. This was before the quarterback married a supermodel, started a family, nurtured a global brand. On their last day together, Brady handed his father his first ring. “Dad, it’s yours.” Touched and a tad embarrassed, Brady Sr. gave it back. He hadn’t earned the bling; the boy he still called Tommy had. After Brady Sr. flew back home to California, his son called. Check your suitcase. There it was. Brady had crept in while his father slept, tucking the jewelry into a carry-on.

The son would collect plenty of rings anyway, and while he was barreling toward his seventh, his father would look at another playoff run and find a poetic symmetry to the first. These Bucs, like those Patriots, suffered a midseason slump that dropped their record to 7–5. They, too, would rattle off seven straight wins, in order to arrive at the Super Bowl, where they would also face a team that beat them earlier that season. Their postseason even included a victory in New Orleans, minus the cigar. “If I didn’t believe in miracles,” Brady Sr. says, “I don’t know how I would characterize this last 20-year run.”

All season, Brady preferred to duck any questions related to New England, as if gliding away from an oncoming pass rush. It wasn’t fair to him, really, this exercise in dividing up legacy, when his is not yet completed. It seemed premature for the arguments that he deserves more credit–70%, says former teammate Shawn Springs–or that Belichick and this Patriot Way made him a legend, rather than the other way around. “The reality is nobody has had the success that Tom and Bill had,” Brady Sr. says. “To say one is more important is imbecilic.” Mike Holmgren agrees. As a San Francisco assistant during most of the 49ers’ dynasty years, he rarely heard anyone pin Joe Montana’s success on Bill Walsh or vice versa. To win that often, franchises need both.

Even then, the events of the first post-divorce season, from New England’s failure to make the playoffs to another Brady run, seemed to bolster Springs’s argument, albeit with a sample size so small that it’s reckless to draw any sort of definitive conclusion. Many will, though.

Opposing AFC players and coaches were thrilled that Brady left, and more for practical reasons than legacy ones. Like Xavien Howard, the Dolphins’ ace cornerback and 2020 Defensive Player of the Year candidate, who used to face Brady twice a season. In Howard’s rookie campaign, in ’16, the GOAT threw a no-look pass on a slant route, summoning Mahomes magic while Mahomes was still in college, at Texas Tech. Howard did intercept Patriots-Brady twice, each occasion so meaningful that the defensive back kept those footballs, planning to prominently display them. “You couldn’t really do nothing to Brady,” Howard says. “He executes on people’s mistakes, and as soon as you mess up, he’s gonna make you pay.” When Brady officially signed with Tampa Bay, Howard says the news was “the best I heard in a minute, because I didn’t want to deal with him anymore.”

Brady and the QB’s camp wish that everyone could view the run of success more like Howard does. Tom House, the QB’s mechanics guru, says the exercise reminds him of something called “Tall Poppy Theorem.” The gist, he explains: When someone overlooks a field of poppy flowers and one stands a foot taller than the rest, their natural inclination is to cut down the tallest poppy.

Sure, Brady isn’t the same quarterback from 2007. But he’s not some journeyman, either. His 40 touchdown passes were the second-most of his career. He’s not Peyton Manning riding a historically dominant Broncos defense to one last ring. Brady simply knew it was time to move on. “He realized that peak had been achieved in New England,” House says. “And with no animosity, he made a decision. He was like a rookie, starting all over again.”

Every year pundits like to pronounce the quarterback as finished, too old, diminished. House laughs. One year they’ll finally, actually, be right. But not this one.

Operation Shoeless Joe Jackson started out, Bucs general manager Jason Licht admits, as no more than a “hope and a dream.” That’s why the Bucs’ front office gave their pursuit of Brady this moniker, inspired by Field of Dreams. As Licht prepared to make the most important pitch of his life, his personnel colleagues would pop into his office, quoting lines from the movie to keep hope alive.

If we build it, he will come, they would say. And more specifically relevant to Licht’s angst: Ease his pain.

“He definitely eased our pain when he got here,” Licht says.

Licht was a southeast-area scout for the Patriots in 2000 when the team drafted the quarterback out of Michigan in the sixth round. The idea that two decades later he would be the GM of a team signing Brady to a free-agent deal? “What are the chances of that happening?” he asks. The Bucs were coming off a 7–9 season in which Jameis Winston, the quarterback Licht drafted with the No. 1 pick five years ago, threw 30 interceptions. Brady was looking for a fresh start and Licht did not see any regression in the QB’s arm strength. “We were very confident that [he] was the missing piece,” Licht says.

The GM wasn’t as confident in Brady’s interest, until he called Brady’s longtime agent, Don Yee, on the first day of the free-agency negotiating window. “You made the right call,” Yee told him. Both Licht and Arians assert that there was a big market for Brady; Arians puts the number of suitors at six. The four teams Brady most closely considered were the Chargers, the 49ers, the Bears and the Bucs. He prioritized warm weather and proximity to his oldest son, Jack, 13, who lives in New York. He also spent the lead-up to his first free-agency tour studying rosters, finding few that could compete with Tampa Bay’s talented skill position players and burgeoning defense.

On March 18, Licht was at Arians’s house, ready to talk to Brady after the new league year opened at 4 p.m. One of the first things Brady said was, “This is going to be a lot of fun.” Licht looked over at Arians and mouthed, “I think this is happening.” In a normal year, signing a six-time Super Bowl–champion quarterback would be the type of occasion on which the new team would rent a restaurant for the entire staff to celebrate. But with the COVID-19 pandemic beginning to shut down the U.S., the celebratory toast was limited to Licht, Arians and Arians’s wife, Christine, at an outdoor restaurant (Christine wouldn’t even meet Brady until Feb. 7).

“It was eerie,” Licht says. “Very representative of this year.”

So, too, was Brady’s transition to Tampa Bay. The NFL and the players’ union agreed to close team facilities and hold offseason programs virtually. That led to Brady forging his own connections with his new teammates. He slid into the Instagram DMs of Mike Evans and Chris Godwin, much to the receivers’ surprise. Cameron Brate needed to verify with other players that the unfamiliar number that had just texted him, asking to FaceTime, was in fact Tom Brady.

In early April, on his way to pick up some study materials from his new offensive coordinator, Byron Leftwich, Brady accidentally wandered into the lookalike house of Leftwich’s next-door neighbor. David Kramer was sitting at his kitchen counter, working from home, when a tall shadow appeared at his front door and the handle turned. “Hey man, what’s up?” Brady asked a confused Kramer, who replied, “You tell me.” Brady suddenly looked like he’d seen a free pass rusher, and he scrambled out the front door apologetically.

Around the same time, Brady was shooed out of a public park that had been closed for the pandemic. That led to Joseph Seivold, the headmaster of Berkeley Prep, a private K-12 school in Tampa, receiving a phone call out of the blue from an alum: Can Tom Brady train there? This, too, was no prank. The school’s classes were virtual at the time, so the campus was quiet and deserted. Brady and a group of Bucs offensive players began showing up at the turf field early enough that the school needed to turn its outdoor lights on. The workouts ran through June, when the Bucs group had to end its sessions a bit earlier, on account of a girls lacrosse camp.

Brate had been to hundreds of throwing sessions before, but he was “super nervous” reporting to Berkeley Prep the first time. It’s one thing to appreciate Brady from afar and another entirely to take his master class in NFL offense. As the QB conveyed exactly what he needed from his receivers on certain routes, he cited some of the defenses they’d be facing in 2020, months before they’d ever game planned. One day, Alex Guerrero, Brady’s longtime body coach, queued up a radar-gun app on his phone to quantify the velocity of Brady’s throws. Still got it.

As spring turned into summer and the mornings got hotter and more humid, the receivers’ stamina was tested. Sometimes Brady would have them stand in the corner of the end zone and work on ball placement, without making them run their entire route. But he’d also push his new teammates, challenging them with Just one more. Evans says he used to barely run routes in the offseason, until Brady became his QB. “I worked out the most I ever have in my career,” he asserts.

On the last Super Bowl Sunday before Brady’s arrival, Ali Marpet was concerned about the amount of Publix fried chicken he’d ordered. The Bucs guard was hosting a small gathering of teammates, in the pre-COVID-19 days, and he placed a food order assuming everyone else would eat like an offensive lineman. At the end of the night, Marpet regretfully sent his teammates home with bags of chicken.

Brate, one of Marpet’s guests, has a different memory from that night last February. “This is a terrible thing to say,” he says, “but it seemed like we were so far away, I couldn't even envision myself playing in the Super Bowl.”

The Bucs were mired in a 13-year postseason drought, meaning that players like Brate, Marpet, Evans and linebacker Lavonte David had never competed in a playoff game. “It’s tough to be the laughingstock,” says Evans, drafted to Tampa Bay in 2014. “Or when teams played us, not respecting us. Like, I am playing the Bucs, that’s an easy win. That s--- used to make me so mad.”

Brady changed the team’s mindset, but it was far from a straight line between his signing and the Super Bowl. Always is. The only other starting quarterback in NFL history to win a ring with two different teams is Peyton Manning. “Tom brought up the fact that he wanted to do what Peyton did,” Arians said.

That comparison would prove to be a deeper one as the season wore on. Similar to Brady, Manning left Indianapolis steeped in an offensive system that he had the ability to run himself. His assimilation to different coaching staffs in Denver, including with Gary Kubiak during their Super Bowl season, was the closest possible reference point, which is why Tampa Bay’s quarterbacks coach, Clyde Christensen, asked Manning for advice a few times this season.

“The best thing that happened was having those games [early this season] where we were terrible on offense,” says Brate. “It really forced [Brady and Arians] to take a look. We found a good balance between what the two are trying to do. That was big, for both of them to not concede a little bit, but come together.”

Arians had taken the Bucs job after a yearlong retirement brought on by health issues, including a third bout with cancer. As he sought his first ring as a head coach, he set about compiling the NFL’s most diverse staff: three Black coordinators (Leftwich, Todd Bowles on defense, Keith Armstrong on special teams) and two female coaches (Lori Locust, Maral Javadifar). As for his playbook and philosophy, he compromised with Brady.

Out of that seminal November phone call came a melded offense that married Arians’s “no risk-it, no biscuit” ethos with Brady’s preference for high-low reads in which he would always have someone crossing in front of him, to whom he could get the ball out quickly on a shorter route. The Bucs did not lose again after the bye week, and they never scored fewer than 30 points in the final seven games of the season.

All those Berkeley Prep sessions steeled Brate for the “uncomfortable” moments that would occur during games, like the time he ran a 12-yard out in the wild-card game against Washington, when Brady wanted him to be at eight yards. “He got in my face a little bit,” Brate says, “but if that situation would arise again, we would definitely be on the same page.”

Everyone adjusted. Chris Godwin remembers his first experience catching one of Brady’s deep throws, which tend to turn over at the top and nosedive into a receiver’s arms—“a very, very receiver-friendly ball to catch.” Nine months later, Godwin would haul in a 52-yard pass from Brady in the NFC championship game.

One play that embodied this merged offense came on the 39-yard touchdown pass to Scotty Miller in the NFC championship game that sent the Packers into halftime reeling. That route—80 Go—had worked against the Raiders earlier in the season, proof that Brady could still throw deep, especially when he had an advantage rather than an edict. “He didn't have those players in New England, where they could just run by people,” Arians says. The sweet spot: mixing those deep plays with Brady’s methodical matriculation down the field. The best of both worlds.

In Tampa, Brady ultimately found what he wanted after he decided to move on. “He wanted to see what football looks like somewhere else,” Arians says. “I have a reputation of being very tough, but having a lot of fun. I think he wanted to see if it works that way. And it has.”

The first home Super Bowl in NFL history made Brady’s actual home a local hotspot as the game approached. He’d moved into Derek Jeter’s waterfront palace upon arrival, the football icon cutting his baseball counterpart rent checks.

Neighbors walked their dogs past lawns decorated with signs as if the NFL had transformed into Friday Night Lights. MY NEIGHBOR IS THE GOAT, read one with a picture of an actual goat wearing a Bucs hat.

Curious onlookers continued to stop by, whether out for a stroll or dropping by on purpose, cellphones out, like on one of those Hollywood celebrity tours. A not-unfriendly police officer stood out front of the black, iron gate, next to his squad car and the manicured yard, his arms folded. The look on his face fell somewhere between bemusement and that of a person wondering what in the hell had happened to this world. He told one group of five that pulled up wearing a mix of Bucs and Patriots gear to take their pictures on the sidewalk.

How many people have come by? “I don’t count,” he said.

Is Brady here? A laugh and a head shake.

One neighbor: “Busy day? Everyone wants to see the house.”

Cop: “You can get a very good picture online.”

The interest, though, spoke to something more widespread: the impact that Brady made in 11 months in a city that never dreamed of the constant, if not occasionally annoying, attention. That sentiment extended into the strangest places. Even at a local dairy, the Dancing Goat, where, it turns out, actual animals are comparable to the football stars tagged with the GOAT acronym.

True story: When the animals compete—think goat versions of the Westminster dog show—they start out by competing in their own age group, usually in two divisions per show. They’re split into seniors and juniors, not unlike Brady and Mahomes. Junior goats are usually favored in the final showcase, because they’re younger, more spry—similar to athletes. Those goats are called kids. But when an older goat takes the goat Super Bowl, owners are even more proud, because it’s harder and rarer and easier to root for.

These goats? They’re called grand champions.

All of which led to Sunday, when the locals embraced GOATs and goats alike. That included Pam Lunn, owner and operator of the Dancing Goat. This summer, as the pandemic raged, her sales dropped roughly 35%. Her expenses, though—$8,000 a month to run the farm, $4,000 just to feed the animals—remained constant. But the attention that her dairy received from the spotlight shining on Brady might save her entire operation, she says.

As Lunn strolled past all her goats on Sunday, she wore a GOAT polo and a black mask stamped with a goat picture. A TV network had asked her to bring her animals to the game, but the NFL said no. So the goats remained in their pens, heads poking out, unaware of the hundreds of times the word “goat” would be used on Sunday. Lunn? In the matter of the Grand Champion vs. the Kid, she knew who to pick.

At Super Bowl LV, even regulars like Brady found a vastly different landscape. The NFL hosted its 269th game during a pandemic that has killed more than 400,000 Americans, after establishing guidelines and responding to team outbreaks. More than 700 players, coaches and staff members became infected with COVID-19 throughout the season.

At Raymond James Stadium, volunteers dotted the concourses holding MASKS REQUIRED signs, while notices lined the fences: COVID-19 warning. Feeling ill? No entry with a fever over 100.4 degrees. Players warmed up wearing masks. The stands held more cardboard cutouts (30,000) than actual people (25,000). Arians wasn’t the only attendee who had been vaccinated; more than a quarter of the crowd consisted of frontline health-care workers.

Even then, some things were strikingly familiar once the game kicked off. The prelude to the first opening-quarter touchdown Brady has ever thrown in a Super Bowl was a springtime conversation between two old friends. Rob Gronkowski had last played in Super Bowl LIII, the Patriots’ 2019 win over the Rams, when the tight end suffered a debilitating quadriceps bruise that capped a year punctuated by injuries. Walking off the field in Atlanta that night, he recalls, “I was so done.” He retired weeks later.

But when free agency began last spring, conversations with his old QB about Brady’s next chapter turned into talks about their next chapter. “Would you come down?” Brady asked. Gronkowski replied, “I’ve been waiting for you to make a move.”

So there was the quarterback’s most trusted target, sprinting across the formation on second-and-five from the Chiefs’ eight-yard line late in the first quarter of Super Bowl LV. When Gronkowski leaked out on a pass route instead of blocking, breaking a well-established tendency, he surprised the Kansas City defense, opening a wide-open path across the goal line. Next, the patented Gronk Spike, this time in historic celebration: Gronk and Brady had combined for more postseason touchdowns than any other duo, this one pushing them past Montana and Jerry Rice. The record stood at 14 by the end of the night. (The tight end also, amazingly, tied the Bucs’ franchise postseason mark for touchdown receptions—in one half.)

The play gave the Bucs a lead they would never relinquish. Gronkowski scored the Bucs’ next touchdown, too, improvising on his route in a way that would only work between two players with the kind of chemistry he and Brady built over nine seasons together in New England. The twist: Two members of the NFL’s last dynasty would help upend the Chiefs’ aspirations to be the next one.

This was a theme of the Bucs’ season, a roster assembled with Brady in mind. One blocker who helped ensure Brady was sacked just once on Sunday night was Tristan Wirfs, the right tackle the Bucs traded up for in the April draft. During camp, Wirfs called his position coach back at Iowa, Tim Polasek, and told him, “I’m in the same huddle with Brady. I just want to make him proud.” The Bucs’ leading rusher in the game, with 89 yards, was Leonard Fournette, who received a text message from Brady soon after he was waived by the Jaguars in late August.

“That was something big for me,” Fournette says, “for a guy like that, who sees my potential, to personally want me to come play for the Bucs.”

Fournette, the No. 4 pick just three years earlier, arrived at the Jaguars’ stadium that day to find a team employee waiting at the gate to tell him the head coach wanted to talk to him.Not being wanted was a new experience for Fournette, who spent the ensuing days with his three kids, going to the park and riding bikes, figuring out what he wanted to do next. “I could have been like, You know what, I’m done. It could have messed up my whole career,” he says. Instead, Fournette took a handoff around the right side on Sunday, following the lead of pulling guard Marpet into the end zone for a 27-yard second-half score that helped put the Super Bowl out of reach.

The Bucs’ roster moves that Brady influenced betrayed a sense of urgency that in the case of the acquisition of Antonio Brown prioritized an on-field edge above all else. Tampa Bay signed the receiver while he was still serving an eight-game NFL suspension, levied in response to Brown’s January altercation with a moving-company employee (Brown pleaded no contest to charges), and his sending threatening texts to an artist, including messages about her children, after she made an allegation of sexual misconduct against him. Brown’s former trainer is also suing him for multiple counts of sexual assault, including an allegation of rape in 2018; a trial is set for December. (Brown’s lawyer has denied the sexual assault allegations.)

Arians said himself on CBS in March that Brown was “not a fit” for his Bucs; seven months later, the team brought Brown in during a spate of injuries among offensive skill players. Licht said that he and Arians had “a lot of conversations” about the signing and did “our due diligence,” though he did not specify what that entailed. Licht also said that Brady “stood on the table for [Brown] when we talked to him about possibly doing it” and cited their prior relationship from the two weeks Brown played in New England. After joining the team, Brown stayed with Brady at his rented waterside mansion.

“He was remorseful enough to get this chance until they decide,” Arians said, referring to the court system, though civil cases can conclude in many different ways, including out-of-court settlements. Publicly, Brown has not demonstrated remorse. During his Super Bowl media session, Brown said he’d be doing a “disservice” to talk about anything not related to the game. He talked about scrutiny, adversity and having “been through some things” rather than addressing his own actions or explaining what work he’s done to earn another NFL chance.

“We’re happy with what he’s been for us on this team this year,” Licht says. Brown had five catches on Sunday. With 10 seconds left in the first half and the ball at the Chiefs’ one-yard line, he turned Tyrann Mathieu around, leaving the All-Pro safety in the dust. His impeccable route created an easy six points—the kind of moment the Bucs evidently determined would outweigh his troubling past.

Back in 2002, when Tom Brady played in and won that first Super Bowl, Mahomes had not yet graduated—as in, not yet graduated kindergarten. He didn’t even play football then, electing for soccer, T-ball and karate classes.

Eventually, Mahomes became a college quarterback who studied film of one legend beyond all others. Brady, of course. Mahomes thought about that after losing in the AFC Championship to the Patriots two seasons ago, after Brady stopped by the Chiefs’ locker room and told Mahomes to “keep being who you are.”

Mahomes’s mother, Randi Martin, sometimes marvels at one picture from the distant past. There’s her kindergartner, clad in a maroon gown and hat, smiling the same Patrick Mahomes smile. That kid will eventually meet the GOAT, a quarterback roughly her age. “I have mad respect for him,” she says.

After Super Bowl LV, as the Bucs celebrated, Martin ran into Brady’s parents, who were typically gracious in victory. They’ve seen this movie 10 times and understand the unpredictable nature of the end.

The Bucs’ defensive front did to Mahomes what the Giants did to Brady in his first two Super Bowl losses, pressuring him without needing to blitz often. Kansas City desperately missed its two injured starting offensive tackles. Tampa Bay sacked Mahomes three times, harassed him into 23 incompletions and generally ignored pandemic restrictions regarding proper social distance. Bowles could not have penned a better-executed plan in a screenwriters’ room. He instructed the Bucs’ D not to allow the Chiefs’ best playmakers to get behind them, he disguised coverages and he emphasized tackling in open space. “He got a little tired of hearing about how unstoppable they were,” Arians says. That pressure netted two interceptions. It also halted any premature comparisons between two iconic quarterbacks at vastly different career stages. For now, anyway.

As the Chiefs return home, Andy Reid must now confront a more important matter than what’s next for the dynasty Kansas City is trying to build. Three days before kickoff, his son and employee, outside linebackers coach Britt Reid, was involved in a multi-car crash that critically injured a five-year-old girl. A local TV station reported that Britt was identified in a search warrant as the driver who caused the crash; police are investigating impairment. “My heart bleeds for everybody involved in that,” Andy Reid said after the game.

When Ross Dinerstein made a documentary about a sushi master in Japan who devoted his entire life to finding the perfect piece of fish, he never expected for the film to resonate in even one corner of pro football. And yet, the executive producer of Jiro Dreams of Sushi heard from three different people in the last month, all of them telling him the same thing: Tom Brady is obsessed with that movie.

It’s true and it makes perfect sense. The doc resonated all over, but in particular with uber-successful types. Fans range from Barack Obama to Arnold Schwarzenegger to Walt Disney executive chairman Bob Iger to Questlove, from the Roots. Asked if that has to do with the film’s protagonist doing the same thing day after day, year after year, never taking a day off, Dinerstein says, “it’s bigger than that.

“It’s striving for perfection, but never being satisfied. I see that in Tom. And I felt that with Jiro.”

Even then, both Dinerstein and Brady connect Jiro’s dreams to Brady’s career in an unexpected way. Both required a full support system to even begin to reach for an unattainable goal, an ideal they’d never achieve because that was never the point. “He found all these people that helped him to do the best job,” says Brady. “Like when he’d go to the fish market, and they would save the special things for him. He couldn’t be who he was without other people doing their roles.”

Brady says he doesn’t much consider his legacy—not now, while he’s so obsessed with football, fully submerged in what Guerrero calls their “healthy illness.” But friends believe Brady cares far more about his standing in football history than he’ll ever admit publicly. He also sees that legacy as tied to more than just him. There’s Guerrero, House, teammates, coaches, support staff; his parents and his sisters; and, yes, Belichick. “You want to go play for them,” Brady says. “You want to celebrate with them. You want to perform for them.”

Over a span of decades, the matter of who Brady really plays for—the people behind his relentless pursuit of the perfect pass—has changed. He played for himself. For his teammates. To be remembered alongside Montana and Jordan and Gretzky and Ali on the Mount Rushmore of all-time athletes. For his mom, as she fought cancer. For his dad, to hand over that first ring.

Now, Brady plays for his own children. Like after the NFC championship game, where Brady bested Aaron Rodgers and clinched that double-digit Super Bowl appearance. This time, he wasn’t looking for his dad. This time, Brady searched for Jack, creating a moment that will live as long as Brady does—which, considering his habits, could be somewhere around 120. “They’re always doing my thing, always coming to my events,” Brady says of his family. “There’ll come a day where I just want to do their things, cause I owe it to them.”

In these moments, Brady seems less like the GOAT and more like a real person whose life changed in ways no human being could ever have imagined. Friends marvel, even laugh, at the evolution: from lovable underdog to elite quarterback to global superstar to wins-too-much villain to, on the eve of Super Bowl LV, something else entirely. Brady became both a sympathetic figure and a (mild) underdog again, even now, his ring collection fitting only on both hands. Full circle, for a circle that’s never stopped expanding in scope.

Other GOATs took notice. Like Gretzky, who knows the selfishness required for someone like Brady to transcend sports. The hockey legend known as the Great One retired at 38, in part due to the time commitment that grew longer every year. In considering Brady’s resume, Gretzky says he doesn’t know football that well but he does consider championships won as the ultimate success barometer. “He’s reached the top of the mountain as far as comparing athletes in each sport,” Gretzky says. “And I know this may sound silly, but as time goes by, years from now, we’re going to appreciate what he accomplished even more than we do today.”

So … wouldn’t Sunday night represent the perfect ending? New team, same podium, enhanced legacy. No logical reason to continue playing. Except that Tom Brady is Jiro. It’s not the fish that matters. “We’re coming back next year,” a member of Brady’s camp says, laughing at the question.

In June of 2016, a little more than a year after Brady won his fourth Super Bowl, beating the Seahawks in XLIX, he attended the Canadian Grand Prix in Montreal. There, on the infield, he bumped into Didier Drogba, the former soccer star and Ivory Coast national team captain. As Formula 1 cars zoomed past them at more than 200 miles an hour, two athletes advancing in age compared notes on stretching, elasticity, recovery and fun-free diets. They tuned their bodies the same way mechanics prepped the eight-figure race cars flying past. Drogba asked Brady how long he wanted to play.

“I don’t know,” Brady responded. “I just want to keep going. I just want to win.”

Drogba pressed the quarterback, elite athlete to elite athlete. Come on. How many championships? Where does this all end? Brady told him that four felt “pretty great.” But then he pivoted, admitting the mark he most desired to match: Michael Jordan’s six NBA titles. Brady idolized Jordan the way that others have come to idolize him. “If I get a sixth,” he said, “I can retire as the GOAT.”

“If you really want to be the GOAT, you gotta try for seven,” Drogba shot back. “If not, you’re only as good as MJ.” They laughed. In that moment, Brady says he thought, only, Man, you’re f----- crazy. But then he won a fifth Lombardi trophy, then a sixth, and then he went to Tampa, and his dad got sick, and his team sputtered, and he took a phone call that saved the Bucs’ 2020 season. Then he lined up three of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history—Drew Brees, Aaron Rodgers, Patrick Mahomes—and eliminated them in the span of four weeks.

“I never could have envisioned this,” Brady says, his seventh championship now secured, his impact and legacy deepening, even by his own impossible standards.

What’s next? Easy answer. This is Tom Brady. He’s gonna try for ring No. 8.

Read more on the Super Bowl