The Year the NFL Banned Two of its Biggest Stars for Gambling

When the Saints lost to the Vikings in the NFL wild-card round in January 2020, it marked a disappointing end to a season that started with swollen hopes. It signified another lost opportunity for Drew Brees to win a second Super Bowl. It also meant that Hall of Famer Paul Hornung had lost a bet he’d placed at the start of the season.

Man Makes Wager On the NFL is not exactly a news flash, given that NFL games come swaddled with ads for betting apps and websites and operators, and millions of Americans have action on football each week. But when, in 2019, Hornung cut the ribbon on a new sportsbook in Indiana and, for a ceremonial first bet, picked the Saints to win the Lombardi Trophy, it marked a significant moving of the cultural chains.

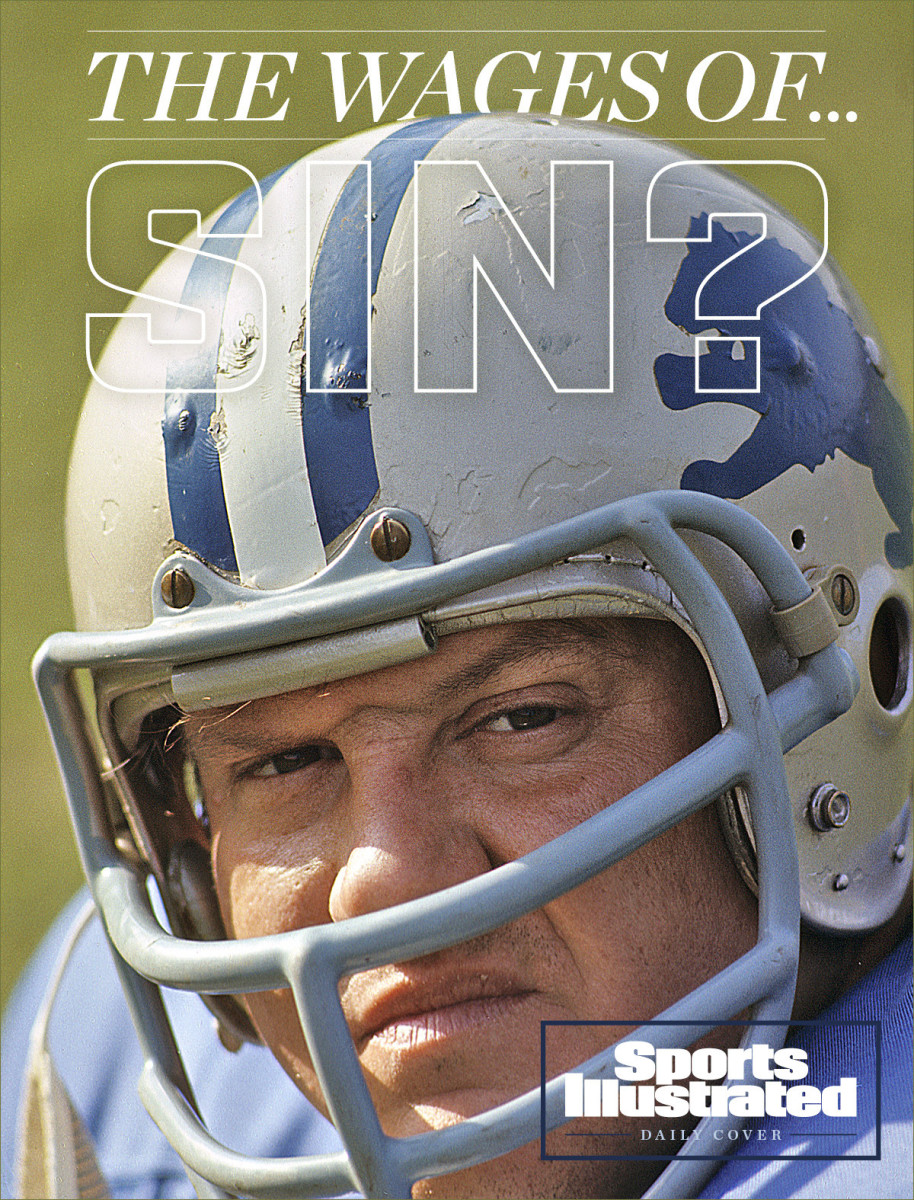

In April 1963 the NFL suspended Hornung, the Packers halfback, for the exact same act: wagering on football. And he wasn’t the only star player exiled for an indefinite period with the possibility of reinstatement after a year. The league’s best defensive player, Lions tackle Alex Karras, suffered the same fate. This would be the equivalent of, say, Aaron Rodgers and J.J. Watt both getting pounded with 16-game suspensions for a “sin” . . . that would later become as much a part of the NFL tableau as tailgating and the Super Bowl halftime show.

For Hornung, it was always Saturday night and never Sunday morning. Almost comically versatile, he played four positions at Flaget High in Louisville: quarterback, running back, receiver and kicker. Bear Bryant recruited Hornung to Kentucky and might have stayed at the school had he landed him. But to win favor with his Catholic mother Hornung chose Notre Dame, where, on account of his athletic pedigree and blond mane, he earned the nickname Golden Boy. Hornung won the Heisman Trophy in 1956; the following year Green Bay drafted him with the No. 1 pick.

When the team hired Vince Lombardi as its new coach in 1959, Hornung’s pro career blossomed. He led the NFL in scoring in each of the next three seasons and was named MVP in ’61. In the NFL championship game that year, Hornung scored 19 points—a rushing touchdown, four extra points and three field goals—in a 37–0 win over the Giants, a record that stood for 56 years.

“You know what made him great inside the 5-yard line?” Lombardi once asked rhetorically. “He loved the glory. He loved the glory like no player I’ve ever coached.”

Hornung’s abilities playing football were rivaled by what might charitably be called his aptitude for cavorting. When he wasn’t drinking or seeking female companionship, he was gambling. Born in Louisville in 1935, Hornung was 14 when he hitched a ride to Churchill Downs for his first visit. He was seduced. Soon, he was working at the joint, first as a teenage usher, then on construction. A not-insignificant portion of his wages went toward wagering. “All I did, really,” Hornung recalled in his 2004 autobiography, Golden Boy, “was seek out fun wherever I could find it. Everything was all tied in together—the drinking, the womanizing, the partying, the traveling, the gambling. And, of course, football made it all possible.”

Weeks after Hornung led Green Bay to the 1962 championship, commissioner Pete Rozelle issued the suspension. For years the league had worried that high rollers and criminal types might undermine the integrity of the sport, and it prohibited employees from betting on any NFL game or event. That season Rozelle had launched an investigation into players’ ties to bettors. As he put it to Sports Illustrated at the time of the ban: “This sport has grown so quickly and gained so much of the approval of the American public that the only way it can be hurt is through gambling.”

Hornung admitted to betting on horses, betting on college and NFL games, even betting on the Packers (though only to win). Starting in 1959, he placed wagers with a gambler in San Francisco that went as high as $500—at the time, more than the median monthly household income. When Rozelle and his gumshoes confronted him, Hornung denied nothing. Rozelle then summoned Lombardi to New York City to lay out both the NFL’s position and its trove of evidence.

“What are you going to do?” Lombardi asked.

Rozelle explained that a ban of at least one full season was in order.

“You have no choice, do you?” Lombardi asked.

“I don’t think so, Vinny,” Rozelle replied. “Let’s go get a drink.”

Hornung was not the only player suspended for gambling and “associating with undesirables” that season. Alex Karras was among the league’s fiercest linemen. A scowling, almost cartoonish brute, he referred to opposing players as “milk drinkers.” Mike Ditka, then the Bears’ tight end, remarked that there were no players tougher than Karras. “He was thought of, at the time, as the best defensive lineman in football,” Ditka said. “I know there was Big Daddy Lipscomb. There were a lot of guys. But he was the best.”

Karras, the son of a Greek-born doctor and a Canadian-born nurse, grew up in Gary, Ind., playing football on parking lots. Though he was expected to go to Indiana, where his older brother played, he committed to Iowa.

Smart, stubborn and as happy matching wits as he was flattening quarterbacks, Karras didn’t take kindly to authority. When he was displeased with his playing time as a sophomore, he threw a shoe at Hawkeyes coach Forest Evashevski, then quit the team. He was reinstated but, as a result of his outburst, did not earn a varsity letter for that season. (Karras and Evashevski never spoke off the field.)

Karras won the Outland Trophy as a senior and was the 10th pick in the 1958 draft. Shortly after joining the Lions, he bought an ownership stake in Lindell AC, a downtown Detroit bar that found favor with sports fans and gamblers.

When Lions brass and NFL executives tried to persuade Karras to sell his piece of the bar, he explained to them the concept of free enterprise. As The New York Times once put it, Karras “deplored the way players were treated like chattel on the one hand, deployed as seen fit, and children on the other, held to restrictive behavioral standards, scolded and disciplined.”

The 6' 2", 248-pound Karras played with such furious intensity that he sometimes turned on his teammates. In a 1962 game against Green Bay, the Lions—as they often did, even back then—lost when they should have won. Leading 7–6, they needed only to run out the clock. But Milt Plum threw an interception, enabling Hornung to kick a field goal to steal the victory. In the locker room Karras allegedly chucked his helmet at Plum, narrowly missing his head. Asked years later to describe his state of mind then, he responded, “Absolutely violent.”

He was similarly enraged a few months later when Rozelle told him of his suspension. Karras had placed at least a half dozen bets on the NFL, including one on Detroit for $100, in direct contravention of league policy. “I also took into account that the violations of Hornung and Karras were continuing, not casual,” Rozelle said. “They were continuing, flagrant and increasing. Both players had been informed over and over of the league rule on gambling. The rule is posted in every clubhouse in the league as well. . . . I could only exact from them the most severe penalty short of banishment for life.”

Two of the league’s biggest names, suspended in the primes of their careers for an entire season? Today, that would, as they say, break the internet. Hornung unreservedly accepted his ban. He apologized publicly and frequently, and felt no animus toward Rozelle. At an airport once, a fellow traveler spotted Hornung and remarked, “What an s.o.b. that Rozelle is. How could he ban a guy for betting on his own team? Worst thing he’s ever done.”

“No, sir, you’re wrong about that,” Hornung replied. “Rozelle was right, and I was in the wrong. When I broke the rule, he did what he had to do.”

To Karras, the severity of the punishment was wildly out of proportion to the offense. He capitalized on his exile by taking part in a pro wrestling match against Dick the Bruiser, noting that the $17,000 he made was more than his NFL salary at the time. He did not hide his disdain for Rozelle, whom he once called “a buzzard.”

Their reinstatement was predicated on a number of conditions. Neither could visit Las Vegas. Hornung wasn’t allowed to attend the Kentucky Derby, much less bet on horses, as long as he was in the NFL. Karras’s reinstatement came with similar restrictions, including the sale of his stake in the bar. During the 1964 season, an official summoned Karras to midfield for a pregame coin toss. “I’m sorry, sir,” Karras said dryly, “but I’m not permitted to gamble.”

Despite missing a year in his prime, Karras was back to being named an All-Pro, and, later, a member of the NFL’s All-Decade team for the 1960s. He played his entire 12-year career with the Lions, though they reached the playoffs just once. Likewise, Hornung played for only the Packers; in two of his final three seasons they won the NFL championship.

Hornung and Karras lived the post-NFL lives you might have predicted. Hornung returned to Louisville, settled down with his wife, Angela, and made good money in real estate development. He also became a fixture at the Derby. For years he was a prominent broadcaster, trading on his name and winning personality. “It’s not a charity golf tournament,” Bob Knight said in 1990, “until Hornung shows up.”

In 1968, Karras played himself in Paper Lion, the movie adaptation of George Plimpton’s account of his foray into the NFL. (Karras and Plimpton stayed lifelong friends.) He got the acting bug, taking guest parts on shows like M*A*S*H*, The Odd Couple and Love, American Style, before taking starring roles himself. To some, Karras is best recalled for portraying George Papadapolis in Webster, starring alongside Susan Clark—his real-life wife—and Emmanuel Lewis. To others, he will be forever remembered as the dim-witted Mongo in Blazing Saddles, punching a horse and uttering the immortal line: “Mongo only pawn in game of life.” From 1974 to ’76, he joined Howard Cosell and Frank Gifford in the Monday Night Football booth.

Meanwhile, the NFL continued—publicly at least—to condemn gambling and project the impression of being shocked (shocked!) that fans were wagering on games, even though handicapper Jimmy the Greek had been appearing on CBS’s The NFL Today for 12 years. (When the Greek was let go in 1988, the league did pressure the network not to replace him with another handicapper.) In 2003, the NFL rejected an offer from the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority to buy a 30-second commercial slot during the Super Bowl. Commissioner Roger Goodell wrote a letter to the governor of Delaware in ’09 condemning the state’s effort to renew its NFL betting lottery. “By legalizing sports betting,” Goodell wrote, “it will be in Delaware’s interest to create ever larger numbers of new gamblers as the state attempts to maximize any revenue found in this promotion. The negative social impact of additional gambling cannot be minimized in a community.”

Hornung and Karras weren’t friends, but a symmetry ran between them. They were the two players suspended in 1963. They both became broadcasters and kept up their celebrity status in retirement. Tragically, they each had dementia and traced the source to football. Karras joined a 2012 lawsuit brought by former players, asserting that the NFL failed to protect him against “the physical beating he took.” (He died months after the suit was filed.) Hornung sued Riddell, the helmet maker, asserting that the company knew of the dangers of brain trauma more than 50 years ago and failed to warn him and other players that their equipment would do nothing to prevent concussions. (He died last November.)

Maybe above all, both Hornung and Karras had to wait to be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Hornung—remember: the 1961 MVP and four-time champion—was not voted in until ’86, his 15th time on the ballot. Karras, the less remorseful of the two, had to wait 45 years for his election in 2020. On Saturday, in Canton, he'll be formally inducted as part of a Centennial Class that had its ceremony rescheduled last summer due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Six decades after their suspensions, the NFL has changed its field position on gambling. After years of denying that it was part of the core NFL experience, the league now freely embraces sports betting as a revenue source. Once a destination so forbidden it couldn’t even buy ad time during the Super Bowl, Las Vegas is not only the home of the Raiders but also a possible future host of the Super Bowl. Gambling revenue is also referenced in collective bargaining agreements, split between teams and players. If sports gambling was going to be legalized in 20 states (and counting), the NFL was going to be damn sure it wouldn’t miss out on a windfall that will approach $2.3 billion.

The same league that suspended Karras for gambling? The announcement of his posthumous election to Canton was broken on the NFL Network—right over the Fantasy Showdown sponsored by DraftKings. Most accounts that followed contained some variation of the word finally.

• Sammi Reyes and the Path Never Taken

• Can Gymnastics Be Saved?

• Inside Alex Cora's Second Chance After Scandal