MMQB: Cancer Helped Ron Rivera Find His Voice, Including on the COVID-19 Vaccine

PROVIDENCE — Eight blocks from this particular hotel lobby, there’s a Rhode Island seafood institution that Ron Rivera loves. He was introduced to it by a good buddy of his, one he went to Seaside High and Cal with, who lives on Cape Cod. It’s become their tradition over the years, whenever Rivera’s NFL team is town to play the Patriots, to meet there the night before the game.

They were there on Wednesday night, and the Washington coach split some calamari with his buddy and his buddy’s wife. Rivera also had a single slice of bread and ordered the Atlantic cod as his entrée, with mashed potatoes and green beans on the side. It’s a meal he always looks forward to, and something he had circled right away when the NFL preseason schedule was released.

But as much as he wanted to, Rivera couldn’t finish his dinner, leaving scraps of fish behind.

“I couldn’t eat it all, and I love the seafood,” Rivera said, about an hour later on a couch at the team hotel. “But I just can’t. It’s too hard to swallow. That’s still frustrating. It’s hard still to taste; I don’t taste everything yet either. So there’s all these little things, these little indicators, that bring me back: You’re not there yet. My wound, my scars, they’re healing, some are going away, but if you look, some are still there. And so every time I shave …”

And this is where Rivera pauses, and recounts the story of the trigger that led to his getting checked out last summer and ultimately being diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma. He was shaving and noticed a lump on his neck. He figured the swollen lymph nodes might be due to strep throat so he went to get tested for that. Doctors gave him antibiotics and told him to keep an eye on it, and Rivera went on vacation. A few weeks later, it was smaller, but still there. He again called his doctor, who told him to monitor it closely for another week.

It didn’t go away. He went in again. He left with a cancer diagnosis.

It’s been a little over a year now, and Rivera never missed a game and wound up shelved only for a few practices. He was the bellwether for a steady Washington team in his first year as coach there, with news-cycle-driving controversies involving the owner and the team’s nickname surrounding his group, and that group won the franchise its first division title in eight years nonetheless. So in a lot of ways, it’s easy to tag him as unshakable.

But that would imply that the last year hasn’t changed Rivera. Which definitely isn’t true.

Less time on the road this week—I’ll be back out next week—but there’s still plenty for us to get to with the first full weekend of preseason games wrapping up. In this week’s MMQB column …

• A dive into where Joe Burrow is going into Year 2 with the Bengals.

• How Brandon Staley’s been innovative with his Chargers program.

• Rams QB Matthew Stafford’s arrival in Los Angeles.

But we’re going to veer off the field to start this week, with a 59-year-old coach who’s been through a lot, and now feels compelled to let world know how he’s come out of it.

Rivera’s a football coach and, while he’s always been one of the more personable ones in the NFL, he’s like a lot of his peers in that there’d long been guardrails on where he’d go publicly. In some cases, he didn’t feel like it was his place to talk. In others, maybe he didn’t think his words would resonate. And then the last year happened. He had to speak on his own situation. He had to speak for the team on situations he wasn’t responsible for.

The result is Rivera has found his voice in a way he hadn’t used it before. So if cancer changed Rivera, and he says it did, then this is where—and he believes it’s for the better.

“As a person, I’ve become a little more of an advocate on things,” Rivera said. “I’ve sensed and feel like I speak up a little bit more on some things. Like the medical issue—to me, it’s the craziest thing that we’re the richest country in the world and we don’t have affordable health care for everybody, that we have a health-care system that’s broken, that I got denied proton therapy [for my cancer] initially.

“Thank goodness our owner and my doctors advocated for this treatment, specifically. But being told that just blew me away. Then to find out more, I had someone reach out to me and say, Hey coach, heard you want to be an advocate for things, would you mind if you told me your story, and I could put it in this book I’m writing to advocate for proton therapy? Which I did. So she tells me the story of this one woman.”

Rivera then shared that story. The woman wanted proton therapy—the treatment Rivera got—to manage her cancer, on the advice of her doctor, who said going through photon therapy instead could make her sterile. She was denied it. She went to appeal the decision, but her doctor told her she didn’t have the time to ride out a lengthy court battle, so she had the photon therapy instead. And the risk her doctor warned her of was realized.

“She lost the opportunity to have children, because she was denied the opportunity to get proton therapy,” Rivera said. “So that’s kind of heightened my sense for social things. I can make a tangible difference for something other than football.”

That, in a roundabout way, brings us to the other example Rivera raised to me about where he’s using his voice—which connects back to his football team.

It’s no secret that Rivera’s been advocating for his players to get vaccinated against COVID-19, and his style has been more forceful than perhaps any of the other 31 head coaches. It’s also well-documented that his own situation, being immunocompromised as a cancer patient, has been woven into the message he’s sending his locker room. But this one’s even more personal for him than you might think.

The form of skin cancer Rivera contracted is a result of the HPV virus. Doctors told Rivera that the virus could’ve been sitting dormant in his system for years (they couldn’t say how long it’d been there for sure) before causing the cancer—and also that if he were younger, he wouldn’t have been at risk. That’s because high schools and colleges now require the HPV vaccine, meaning that, because they’ve gotten, yes, a vaccine, the players he’s begged to get vaccinated for COVID-19 aren’t as at-risk as he was to get the cancer he did.

Suffice it to say, Rivera didn’t need to be asked twice if he wanted the COVID-19 vaccine. His group of the immunodeficient was second in line for it nationally, behind only health-care workers and the elderly, so the Washington coach got his first shot in January and his second in February. Even still, because of his condition, he can’t let his guard down. In the team hotel Wednesday, he wore a mask, and he held it in his right hand as we talked.

“I have to be careful, I have to wear these,” he said, shaking the mask. “We’ve had a couple situations with players already testing positive for COVID, and that scares the hell out of me, because I interact with these guys. I’m close to these guys, and sometimes I forget to put my mask on for extra insurance. I know I’m vaccinated, and I know it’s going to keep me from getting deathly ill, but I can still get it. And who knows? So I have to be careful.

“There’s enough positive science out there, if they’re going to tell me that over 600,000 people have died and 99.9% are people that were not vaccinated, well, what about the .1%? Well, that .1% are people that had underlying conditions—old age, something else. It’s not young, healthy people. So I don’t know why. And then they talk about all this distrust, well, if half the world wants it and can’t get it, what’s the problem with us? It frustrates me.”

Over time, Rivera thinks he’s actually learned what the problem is, and it’s one we’re all pretty familiar with.

“I had a player come to me when we first got back and we’re getting ready to go to camp,” Rivera said. “He came to me, and he had a big smile and said, Hey coach, just got my second vaccine. I said, Right on. He said, Had to, mama, new baby, got to, coach, gotta be careful for others. I said, That’s great, plus with that variant … He looked at me and said, What variant? I said, You know, the new delta variant, you know about that?”

The player in question had no idea. Rivera asked if the player watches the news. The player said no, and raised his phone to say, “I get all my information from here.” Which, right there in the moment, Rivera recognized as the problem.

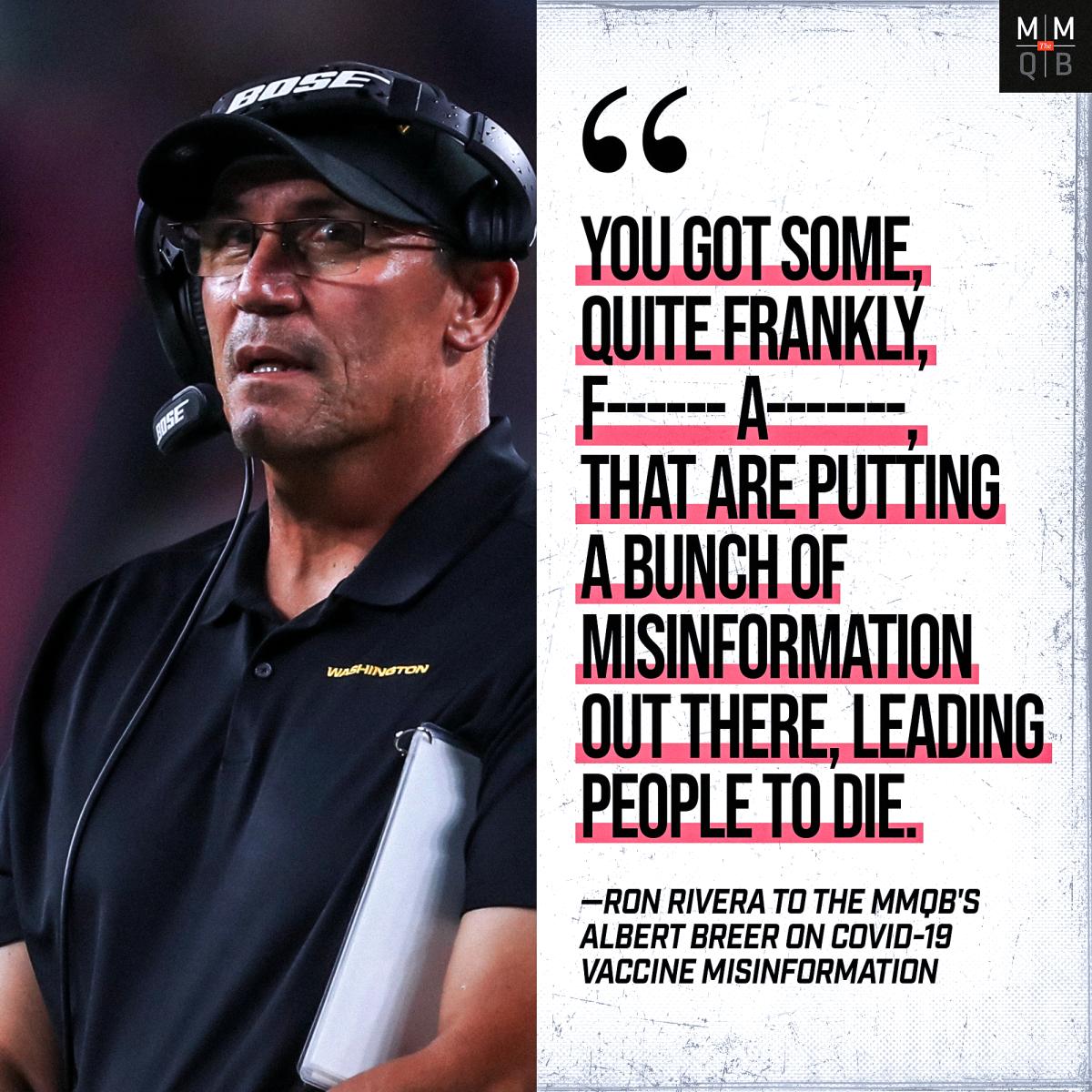

“Gen Z is relying on this,” said Rivera, now holding up his phone. “And you got some, quite frankly, f------ a-------, that are putting a bunch of misinformation out there, leading people to die. That’s frustrating to me, that these people are allowed to have a platform. And then, one specific news agency, every time they have someone on, I’m not a doctor, but the vaccines don’t work. Or, I’m not an epidemiologist, but vaccines are going to give you a third nipple and make you sterile. Come on. That, to me? That should not be allowed.”

Rivera has his football reasons to want players to get vaccinated too, of course—he raised to me that he had two unvaccinated players knocked out on contact tracing in camp, and that if that happened the morning of the opener, those guys would miss two games (since WFT’s Week 2 game is on Thursday night). But clearly, it goes deeper than just that for Rivera, and it stands to reason that the uptick in vaccinations ties to Rivera’s feelings on it.

Regardless, he’s definitely not going to be quiet about it again.

On one hand, Rivera feels compelled to speak up, because going through what he has will give a man perspective on life outside of football. On the other, it made him appreciate what he has, and there were moments last year, to be sure, when he took time to really take in how much being able to coach his team means to him.

It most commonly would hit him from the front seat of a golf cart Club Car gave him.

Every day, before practice, he’d get a ride down to the Ashburn, Va. fields on it, and it’d be parked near the sideline in the shade. It was there in case he needed to get off his feet for a second, and that’d happen about once a week—usually on Wednesday, because that was the last of three straight days of cancer treatments every week. And sitting there would give him a minute to think and contemplate how he was pushing through the fatigue.

“Every time I had to sit down, it would just … I’d put my leg up and be like, f---, this is tough,” he said. “And it would really kind of well up. But every time I’d get up, I’d feel a little something extra. So I’d say the moments I’d have were when I’d sit in that cart and just look out and think about, Man, you gotta go. Let’s go.”

There were tougher moments than those, of course. There was an episode where he was getting proton treatments, his throat got dry and he couldn’t get himself to sit still—which is a must to the point where they strap patients in with an immobilizing mask—and needed to be told by his oncologist, Dr. John Deeken, and radiologist, Dr. Gopal Bajaj, that he absolutely couldn’t miss a treatment. They gave him special throat lozenges, a cup of water and his wife Stephanie, and that steeled his nerves.

“As soon as that first click [on the mask] went in, I said, Alright motherf-----, we’re getting through this, this is for your own f------ health, you need this and you can’t f------ back down now. Everybody’s counting on you, so let’s f------ go,” Rivera said. “And for the rest of my treatments, that’s what I did.”

Then, there was Oct. 6. That morning, he went through treatment, and Stephanie drove him to the facility. When they pulled into his parking spot, he told his wife, “I can’t get out of the car. You guys gotta help me.” So she pulled the car around to the back of the building, where head athletic trainer Ryan Vermillion helped Stephanie carry him out of the car into the facility. Rivera could see the looks on the faces of the players there, about 25 to 30 of them, on players’ day off, which he read as, “This dude looks bad.”

He would up going home and sleeping from morning into the 6 p.m. hour, at which point, Stephanie got worried and tried to wake him up. She wound up getting Washington’s team doctor, Anthony Casolaro, on the phone, and, in Rivera’s words, Casolaro “basically read me the riot act.” Stephanie got some bone broth that ex-Panthers RB Jonathan Stewart had sent his former coach out of the fridge, made chicken noodle soup, and Rivera, down 40 pounds at that point, forced himself to eat it.

“It was the first time I’d eaten that much; it was the first time I’d slept that much,” Rivera said. “And things just start to roll. From that point on, I could see the light at the end of the tunnel, I really could.”

He’s not out of that tunnel yet. He couldn’t finish that fish he loves so much on Wednesday night. The following day, he arrived at Gillette Stadium ahead of the team so he could get an hour nap there—because he’s still afraid to oversleep if he takes his nap at the team hotel. And anytime he feels good, and maybe like he can just let it rip again, he gets reminders.

“I do pace myself right now, so there is some of that frustration, that I’m not where I was,” he said. “So that’s the hard part. And a lot of people don’t know that. When you go through something like this, they tell you it’s 12, 16, 18 months. It is. That’s what the recovery is. It takes a while. I still have the tingling in the hands and the feet, I still have the acid reflux stuff, I still have tightness in my neck, I can’t turn it quite yet. I do my swallowing exercises.”

But as he sees it, there’s benefit to all this too, and he genuinely believes his team felt that benefit in 2020. The group had to manage COVID-19 protocols like everyone else, and also the nickname change, the workplace culture controversy and tumult at quarterback, and did it with leaders like Rivera and Alex Smith, who were overcoming their own personal challenges to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the rest of the team.

And sure, the NFC East was down, and Washington won it at 7–9. To focus on just that, though, would be missing how it happened—after all of the above and a 2–7 start. So when the season ended with a loss to the Buccaneers, while Rivera wished for a better ending, he was also able to appreciate crossing the finish line.

“It was very gratifying, because I did make it, and I didn’t miss a game, and that was part of it,” he said. “I’ve coached better teams, but I don’t think I’ve coached a team with this kind of resilience, and I can’t help but wonder if all the things that we’ve gone through was reflected in the way that we managed last year. … Believe me, I would’ve loved to have beaten Tampa and kept going. And when we lost, it was a very emotional thing for me, because I knew I was different.

“I do look at things differently, I do appreciate things differently.”

As much as anything, you can sense how grateful Rivera is now. For Stephanie. For Casolaro, Deeken and Bajaj. For so many people in the organization who pulled the rope when he couldn’t. For his son Christopher. And for his daughter Courtney, especially, who works in social media with the team and would routine call her dad out if he told the doctors he was fine when he really wasn’t—so he could get the rest he needed.

“The other thing that we found out was that when a male is diagnosed with cancer, and he has a caregiver, he will do well,” Rivera said, smiling as he made his point. “If he has a female caregiver, he’ll do very well. If he has his daughter as his caregiver, he will do exceptionally well. Nobody takes care of dad like his daughter. … She was constantly on me. That was one of the cool things I found out—no one takes care of you like your daughter.”

He’s also grateful now just to be able to coach.

That much was clear to me when he and I talked about his team, and not his own personal condition. He likes where his roster is and thinks this year will be a good test of its maturity—keeping a team relevant, he knows, is often harder than making it relevant in the first place. He’s excited to have his staff back largely intact, and a remade scouting department of trusted confidants like Martin Mayhew and Marty Hurney.

When we went through that stuff, Rivera didn’t much raise his own situation, and that, for him, was a healthy thing. But it was never far away either.

Asking him why he’s doing this after all he’s been through was another reminder of that, and how what he’s been through, and is still going through, is woven into every piece of his life. After all, he’s won a Super Bowl as a player, been to a Super Bowl as a coach and turns 60 in January. He’s also a cancer patient, and so the idea of retiring home to the West Coast did, indeed, cross his mind—“Oh, you do think about that. You do think about that.”

So why is he grinding through another training camp, under the stifling humidity of Northern Virginia, with another long season ahead?

“Because I still love the game. I love the game a lot, I really do. I love everything about the game,” Rivera said. “It’s interesting because it took me back to why I took this job, I just feel like I’m supposed to have this job. Think about this, there’s only 33 proton therapy machines in the United States. And three of them are in that area—Johns Hopkins, Georgetown and Nova in Fairfax. There’s three of them, and there’s not one in North Carolina, there’s not one in Northern California. My hometown, there’s not even one close.”

So if he were still with the Panthers, or back home, he’d have needed to go away for seven weeks to get the treatment. Doable? Sure. But coaching would’ve been impossible.

“I’ve always felt like, and Stephanie says it, we’re here for a reason,” Rivera continued. “And if I quit now, I’ll never find out if there really is a reason. So at least I gotta go through this, I’ve gotta see this and get through it. I do want to do a lot, I do have a lot left to accomplish. I do want to win a Super Bowl, not necessarily for me, but for the people around this, the people that are part of this. That’s what my goal is.

“If I can do it on this contract, great. If I can’t, we’ll see what happens. But that’s why I do it. Somebody will say, Oh, he’s crazy, he’s one of those. But, s---, it’s how I feel, it’s how my wife feels. … I just can’t help but think, there’s a reason. And, again, maybe I’m a little dramatic about that, but what the hell? We’ll see.”

JOE BURROW'S PROGRESS

CINCINNATI — I was here before things seemed to go the wrong way for Joe Burrow, so a lot of my discussions at Bengals camp on the second-year quarterback centered on the steps he’s been able to take despite coming off December ACL surgery. Which we’ll get to in a second.

But given all the noise around Burrow, it made sense to dig around a little more on the bumpy stretch of practices he had a few weeks ago that drew headlines and resulted in skepticism on how ready he’ll be for the team’s opener against the Vikings on Sept. 12. And it’s actually, on the surface, pretty normal stuff for a quarterback coming off this sort of knee reconstruction.

Really, it was a product of Burrow’s mental state being tested in a way it hadn’t been before.

See, from February, when he returned to Ohio from California, through the first week of training camp, Burrow steadily kept adding to his workload in different ways and kept progressing as he and the team moved forward. But until the middle of the first week of August, it wasn’t real football. The spring was stocked with walkthroughs, with a few live seven-on-seven scenarios sprinkled in, and the initial 11-on-11 work of camp wasn’t in pads.

Then, the Bengals put the pads on, went 11-on-11, Burrow had guys buzzing by him and, even with the quarterback no-contact jersey on, he felt a real rush for the first time since one led to his knee’s being shredded in Washington. The coaches noticed he was picking up his leg early to protect himself. His eyes dropped, and he’d look at the rush. He wasn’t throwing on time. In short, he wasn’t himself.

“Seven-on-seven and routes on air was fine. But then first couple days when people got around me, it took some getting used to again, to be able to feel the pocket like I used to,” Burrow confirmed to me on Sunday afternoon.

After a couple of days of that, the coaches noticed Burrow’s frustration was simmering—a quarterback who’d always thrived on his own confidence was suddenly lacking it. The important thing? It was acknowledging what the problem was, and that it was real and something he had to address.

“It was just getting reps, getting people around me again,” Burrow continued. “After one of the days where I didn’t play so well, we went out early the next day, and they were throwing bags at my legs while I was throwing, we were simulating a pocket with some dummies, and they were doing it during seven-on-sevens and individual routes. And after that day, it was really back to normal.”

At first, the frustration was rooted in its coming as an unpleasant surprise. He didn’t expect it to happen like it did, because everything had gone well to that point. But once he was forced to confront it, he recognized it was something he’d been warned about, and something even guys like Carson Palmer and Tom Brady weren’t immune to. “It was the last part of the rehab process, really,” he said. “And that’s what everyone had told me, that was going to be the last hurdle to get over, and we got over it.”

Now, he feels like he’s back on the track he’d been on, and that track is trending to where he can pick up where he left off when his season ended in Washington.

And that point of reference is important, because of how well the Bengals felt like Burrow was playing at that point. When he went down, there was 11:41 left in the third quarter, and he’d already thrown for 203 yards and a touchdown while 22-of-34 throws against the fearsome WFT front and staking the Bengals to a 9–7 lead. More than just that, it was a continuation of where Burrow’s game had gone over the month previous.

“He had taken ownership, was really comfortable with what we were doing on offense, and we found our rhythm in how we wanted to play last year,” Bengals coach Zac Taylor told me. “You look at his last four games, we played Cleveland here, we had two turnovers and we never punted the ball, so we felt like we were moving the ball. Played Tennessee, and all our linemen went out, five new linemen, and we beat a good Tennessee team really because of his ownership of the system, just finding completions, moving the ball.

“And we went to Pittsburgh, and it was tough, great learning experience for him, on the road, divisional game, 4:30, it was our first late-afternoon game, all that went into that. And then he comes back and rebounds against Washington, and really he’s playing his tail off against Washington and one of the best fronts in football. They gave up the fewest passing yards, and at halftime he was pretty well on his way.”

“He was ascending at a rapid pace,” coordinator Brian Callahan added. “There were a couple weeks there where finally everything had slowed down. And he was starting to see things that guys see typically maybe three, four, five years into their career, because he’s got such an unbelievable ability to process what he sees. We were starting to go more at the line of scrimmage, allowing him to diagnose and get us in the big plays.

“Obviously, we’d assist where we had to assist and we had plans in place but his ability to see, process and react at a really, really fast pace was getting better and better.”

Since? According to Callahan, “He attacked the offseason with the kind of a fury that I haven’t seen from many guys. I don’t think he took a vacation. He was on a mission to get back.” And while that might be a slight exaggeration (he did go to Florida over the NFL’s summer break for a few days), his work was pretty constant regardless of where he was, and that’s shown most in places other than the practice field.

In fact, it’s at the point now where Burrow’s running some of the team’s evening offensive meetings.

“He tells them what he expects and how he wants it, and that’s ideally in this league how you want it. He’s an extension of the coaching staff, as starting quarterback,” Taylor said. “You want him to get to that point, and that’s really where Joe is at, understanding why we’re doing things, and then him taking the ownership, and let the guys play for him.”

Callahan, for his part, has seen that sort of thing before. When he was a young Broncos assistant, he remembers the coaches sitting in the back row of the meeting room while Peyton Manning commanded the clicker, only chiming in as needed. He was also with Matthew Stafford in Detroit, and saw Stafford take similar ownership of the Lions’ offense.

Burrow doesn’t have the clicker yet. But as the coaches see it, he will soon, and the fact that he can command the meeting room at his age is a sign of just how far ahead of most young quarterbacks he is.

“We’ll be in the unit meeting, and it’s generally with the skill positions, the line’s usually doing their own thing, and we’ll turn play on, and, Alright, Joe, go ahead,” said Callahan. “He’ll tell Tee [Higgins] on a route, Hey, I need you to lean more on this route, so I know when you’re gonna trigger. Or Make sure you don’t lose leverage on this guy. He’s got such a great feel for what to expect. … I can get up there and say the same exact thing. It means so much more when the guy pulling the trigger is the one telling you what he wants you to do. …

“That’s always what great offenses do, that’s what great teams do. Really, the best coaches guide and teach and give information. The guys on the field are the ones on the field, and they gotta be able to do it, they gotta be able to fix problems. The best offenses, the best teams, are run by their players.”

Burrow, for his part, says that area—fixing problems—is where he really was taking leaps just before he got injured. And as excited as he was about turning that very real quarterbacking corner, he’s just as excited to build off that. That’s why his main goal has been to pick up where he left off in November, and in a roundabout way, it’s why he feels like going through what he did a week and a half ago will help him get there.

Bottom line, he was going to have to confront that challenge at some point, and it’s better that it came in August than September.

“I’ve put in the work to pick up right where I left off, that’s the goal,” Burrow said. “I guess we’ll see Week 1, in a couple weeks, but I’d like to pick up where I left off. … The biggest thing was me understanding the offense enough to get us out of bad plays and into good plays, and to see what the defense was trying to do, and check to a play to counter that. And I was starting to do that really, really well, getting the ball out of my hand quickly.

“I was excited about where I was going, I was getting better each week. And I’m starting to feel it in practice again. Like I said, we started to pick it up again last week, and I’m starting to feel like where I was last year.”

Which is really good news for the Bengals, after what they hope they’ll only remember as a tough couple of days.

BRANDON STALEY'S STAMP ON THE CHARGERS

COSTA MESA, Calif. — Yoga isn’t what you’d first expect to see when you get to an NFL training camp, but there I was on that Friday morning in Orange County seeing it with my own eyes: dozens of overgrown athletes practicing the ancient art on a set of football practice fields.

The purpose of it, for first-year Chargers coach Brandon Staley, is pretty straightforward. It’s what’s called, in sports-performance parlance, an activation period, designed to get the players’ bodies warm and ready to practice. Lots of teams have activation periods.

But seeing it on the field, in this setting, was different. And so when I got together with Staley after practice, it was the first thing I thought to ask about as we dove into what’s a different practice schedule in general—the Chargers were only out there for about 90 minutes total. What I found out is that the idea of it runs much deeper than just what I witnessed Joey Bosa, Derwin James, Justin Herbert and their teammates doing.

“When I got my shot, I really wanted to be a team of teams,” Staley said. “It was really lengthened across all phases—football, sports performance, personnel. Those are the teams that stand the test of time. I want our offense to know how we play on defense. I want our defense to know how we play on offense. And then I want them to know how we bring it all together in the kicking game, and I think there’s a lot of benefit to that.

“Corey Linsley can help Linval Joseph. I think Derwin James can help Justin Herbert. And I think you bring people closer and they get invested because they know what’s going on. And it’s the same thing in sports performance and all the other things we do. This is the reason why we’re going to meet the way we do the night before at the hotel, this is the way we’re going to travel on the plane. I wanted the way we play, and then the way we train and prepare and perform, I wanted all that coming from a central place.”

Then, Staley interlocked fingers, explaining that rather than being a top-down operation, he wanted the different facets of the organization to fit together like puzzle pieces. And from there, Staley pointed to the place he’s so often associated with, as people try to illustrate just how quick his climb has happened: Div. III John Carroll University.

So, yup, where a lot of people have knocked Staley, Staley believes he draws his edge, as he heads into his first year as an NFL head coach.

Truth be told, even before getting there, Staley’s path was unorthodox. Tom Arth got the head coaching job at John Carroll in early 2013 and landed his first choice for defensive coordinator: Case Western assistant Jerry Schuplinski. But two months later, Patriots OC Josh McDaniels came calling for Schuplinski, and lured him to Foxboro to be a quality control coach. Arth was in a tough spot, and his high school teammate Jonathan Gannon, then a Titans assistant, recommended Staley: “Bring him in, you’ll see.”

Arth now says it took him 30 seconds in Staley’s interview to see it. And what followed that spring was a set of deep talks on program-building philosophy.

“It was really immediate for us,” Arth said. “We’d just finished spring ball, and first thing we did, we watched all the games, the practices, to get to know the players we were coaching. We had strong beliefs on how we wanted to play, what that looked like. We both wanted to coach like we were in the NFL, so we were gonna coach them just like we’d coach them if they were the Cleveland Browns, and run the organization like it was an NFL organization.”

And the result was reflected in how Arth, now the coach at the Univ. of Akron, addressed his team before it started fall camp a couple of weeks ago—he told them that, on average, they had a little less than 30 hours between each practice, and it was up to everyone to make the most of those 30 hours.

The overarching idea, of course, is that, like Staley said, every minute is thought out and explained clearly. Which leads to having a holistic program.

“You want to go through the plan with the team, where they feel like, O.K., everything they’re talking about, the situations they put us in, they’re doing it because it’s gonna help us perform better,” Arth said. “Everyone’s on a 24-hour clock, that’s where we’re equal, so how can we stretch that time? How can we operate off a longer day, and allow players to be as fresh as they can be, so they’ll able to learn in meetings, retain it and apply it at practice, where their bodies feel great, too? You build it all from the ground up. And everything matters.”

That much was reflected in the tightly-wound practice schedule Staley showed me. The yoga? Staley wrote it into that schedule, because while most teams offer an activation period, oftentimes it’s an option. He thought it was important enough to require it. So that went from 8:45 to 9, with 10 minutes of stretching to follow, before individuals started at 9:10. The 11 periods of the session wrapped at 10:30, with the defense’s going in to lift, and the offense’s taking part in a mandatory post-practice stretch.

To be clear, while the overarching every-minute-counts approach did come from Arth and John Carroll, Staley’s taking things from working with John Fox, Matt Nagy, Vic Fangio and Sean McVay in the NFL, too. He also credits Rams VP of sports performance Reggie Scott as an influence (especially with the importance of the activation period), and poached his own director of sports performance, Anthony Lomando, from Fangio and the Broncos, which is a sign of what he thought of their program.

And there’s no question that it’s touched every piece of the schedules Staley has made out. From McVay, Staley took the idea of loading up the players with work in walkthroughs, so they could get the time on task they needed mentally without putting miles on their bodies. From his NFL experience in general, he decided to build his camp itinerary to emulate game weeks, to condition his players for the season.

“You just gotta realize these guys only have so many bullets in the chamber,” Staley said. “They’ll go—they can and they will. But for how long, and how dense is that work? That’s something that I’ve learned a lot, and I’ve tried to bring here. So that when we’re out here, like today, it’s like, Hey guys, we can go today, you can give it everything, you don’t need to pace yourself, we can go.

“I don’t want a two-hour practice and then guys are pacing themselves for a half-hour, then they practice.”

The result, both Staley and Arth emphasized to me, is players’ seeing a program that’s invested in getting each guy in the best position to be his best—and moreover, the leaders of that program explaining why it’s the way it is. And after talking with Justin Herbert, who’s been working in-house with the new staff since February, it was pretty clear to me the message is getting through.

“The mindset behind it is the Chargers have been plagued by injuries the last couple years late in the season,” Herbert said. “It’s a long, long season of football, you have to be ready for 17, 18 games, hopefully more in the playoffs. And I think what they’re trying to do now is really build your body up. They’re doing three days on, one day off, recovery day, and then building it, slow it down, giving us a lot of time to stretch, warm up, do things so when we go to practice, we’re able to go.

“I think it’s all for the players, and I know the older players are appreciative of it, talking with Chris Harris and Bryan Bulaga, that’s kind of what they’ve advocated for.”

And sure enough, the Chargers’ injury issues of the last few years—that really stretch through multiple head coaches—were raised by Staley all the way back in his interview in January.

It was a point of emphasis because of who he was interviewing with, of course. But really, the overall idea would’ve followed him wherever he went.

“It’s the mindset—there’s no such thing as bad luck,” Staley said. “There’s no such thing as being cursed. I’m a former cancer patient. There’s no such thing. It’s your mindset, and your approach. And our approach here is to be our best for our players, period. That’s the approach. And we are not going to think like that, we’re not going to act like that, there is no such thing as that. And that’s what I told everybody that works here. …

“From a mindset standpoint, from a competitor’s standpoint, I wanted to change the competitive mindset of this team, and really specifically pour into the Chargers, and stop worrying about everything on the outside—this team, that team, in the division, across town, what happened in the past. Let’s just pour into this team, the people in our building, and let’s see where it goes.”

That, at very least, has very clearly happened. And the yoga sessions—another thing Staley was first a part of back at little ol’ John Carroll—are proof positive of that.

MATTHEW STAFFORD'S COMFORT IN L.A.

IRVINE, Calif. — The most impressive thing I saw from Matthew Stafford on my camp trip actually came the day after I visited the Rams at UC Irvine. That was in Oxnard, where the team scrimmaged the Cowboys, and it came in the sort of throw we’ve all seen the 33-year-old make. He rolled to his left on the play and, with the rush bearing down, whipped his body around to hit DeSean Jackson, racing to the pylon down the opposite side of the field.

It was the sort of throw maybe a half-dozen NFL quarterbacks are capable of making.

It was bananas.

But the most impactful thing I saw on Stafford during the two days I was around him? How happy all the Rams people are to have him—you couldn’t run into anyone in Irvine without getting a feel for how good they all think Stafford is going make a team that’s been in the playoffs in three of Sean McVay’s four years at the helm. And how happy he seems to be.

It was obvious, to me at least, in how Stafford’s carrying himself, and also how he carried on in explaining why the Rams were an attractive destination to him even before he was traded here. He maintains now that, “I had honestly zero idea it was a possibility until the week before it happened,” but says he saw enough watching the team on TV, seeing them on tape the last few years and just hearing about what McVay’s operation was like.

“Great culture,” Stafford said, in a quiet moment after practice. “It’s the offense, yes. But it’s a great team. No. 1 defense in the league last year, bunch of young talented players on that side of the ball, two all-time greats on that side of the ball and then some really talented dudes on offense, some guys that have made plays for quite a few years in the league. And then some young guys that are gonna come on as well.

“The players on this team were a bright spot when looking at them from afar. Sean as an offensive coach, no doubt, what he’s done has always been very innovative, always forward-thinking and trying to put his players in the best position to succeed. He and the whole group here have done a great job of creating a culture of enjoying what you’re doing, loving the game, playing hard, playing fast. And a bunch of recent success, which was a lot of fun for me to look at from afar.”

And it’s fair to say now, for a number of reasons, that Stafford’s perception of the place has matched up with the reality of his arrival in Southern California.

Like he said, it’s the up-tempo, upbeat nature of the group, to begin with, and that Stafford is around not just Aaron Donald and Jalen Ramsey, but peers with skins on the wall like Andrew Whitworth, Robert Woods and Cooper Kupp. It’s also, of course, the natural shot that a fresh start will give a player, and I’d bet the weather doesn’t hurt either.

But just as much, it’s a mutual belief that, just maybe, this move is going to unlock another level of play in Stafford.

That part is less about obvious things, like his capability of throws like the aforementioned one to Jackson, and more about where Stafford’s experience and mind can take the offense in partnership with McVay. That piece—Stafford’s football IQ—was long considered by his coaches in Detroit as an underrated part of his game (remember, he played for coaches who worked with Peyton Manning), and something McVay could see right away when No. 9 got to town. Since, the two have melded Stafford’s diverse experience to the Rams scheme.

“I’ve had exposure to a lot of different offenses, a lot of different ideas, a lot of different ways to do it on the offensive side of the ball, this one being a brand new one to me,” Stafford said. “But I do bring some past experience, whether that’s good or bad, as a sounding board, as information, just here to listen, here to share my opinion, here to say, Hey, I’ve done it this way and it’s worked, or this way and it didn’t.

“And whether it sticks or doesn’t, I have no feeling towards that. I just want to be as open and honest with all the stuff that I’ve ever done, and I feel like it’s a two-way street. Sean’s obviously built this thing and had a ton of success, and has an idea of how he wants it to look and how he wants it to feel. And I’m trying to do everything that I can to make sure I’m running this offense at the highest level. But at the same time bringing my own feel to it.”

In illustrating that, Stafford cited some of the no-huddle/tempo elements he learned under Jim Bob Cooter, the tried-and-true older-school concepts of Scott Linehan, as well as the Seahawk and Saint influences of Darrell Bevell and Joe Lombardi.

McVay, for his part, has been receptive, as have coordinator Kevin O’Connell and the rest of the offensive coaches.

“It’s been great, constant dialogue, talking about things they’ve done in the past, things I’ve done in the past, things they’ve had success with and I’ve had success with, and just trying to fit that to the guys we have on this team, with the particular skill sets they have,” Stafford said. “And you just rely on those guys to put them in position for our guys to win, which they’ve done a great job of.”

For Stafford, that’s also spilled over to working with Woods, Kupp, Tyler Higbee and the rest of the skill players on his own too, to try and get things where they need to be—“It’s new for everyone, and me, so I’m just trying to be as good of a communicator as I can be.”

From what I can tell, the result will be what can best be described as a new version of the Shanahan-styled offense McVay brought with him to Los Angeles five years ago, one built to bring out the best in Stafford specifically, and the scheme as well. And since the Rams don’t play their starters in the preseason, you won’t get to see what that looks like until they open the season on Sunday Night Football against the Bears.

But rest assured, Stafford, McVay and the rest of the Rams are pretty pumped to show everyone what it’ll look. And that much was easy to see in Irvine.

With a smile, Stafford said to me, “I feel like I’m where I need to be.”

In saying that, the quarterback was referencing where he’s at in learning, and helping to build, the offense.

But in a big-picture sense, he feels that way, too.

TEN TAKEAWAYS

The calls coaches have to make on the first-round quarterbacks are different this year. And that’s because where normally those types of rookies are on bad teams—usually those in position, and in need, to take them are in dire straits—this year, three of the five, are on teams that have contended of late, and have reason to believe they’ll contend again in 2021. Trey Lance is playing for a team that was in the Super Bowl 18 months ago, Mac Jones is on one that won it 30 months ago and just completed the most successful 20-year stretch in league history, and the franchise Justin Fields went to has been in the playoffs two of the last three years and is top 10 in the league in wins over that stretch. All have rosters stocked with accomplished veterans. As such, all are naturally going to be a little less tolerant of riding out the inevitable bumps a rookie quarterback is going to endure. So while I’m not saying that Lance, Fields and Jones won’t play this season, I will say that the decisions Kyle Shanahan, Matt Nagy and Bill Belichick have to make are different than those Urban Meyer and Robert Saleh are in the process of making. And remember, if the rookies don’t start Week 1, the coaches can always pull the rookie-quarterback lever later on, whereas it’s much harder to go back to the veteran if you start with the rookie.

That said, Jones looked very comfortable in his debut. And I think that’s the best thing you can say for the Patriots’ first-round pick—the operation looked clean, he ran the no-huddle confidently at the start of the second half, the ball was out on time and there really wasn’t anything that looked too fast or big for him (which makes sense, given that he played in a program that basically mirrors the pros in a lot of ways). Specifically, the negatives I gathered were that he aimed the ball a little too much after he first got in the game, and that there were a couple of shots downfield there for him that he didn’t take. But overall, he made the Patriots offense look like the Patriots offense we’ve seen run for the last 20 years, and the coaches showed confidence in him in one very real way. Five of Jones’s 19 pass attempts on the evening were out of empty formations—meaning that there were just five guys blocking for the quarterback, and that he personally had to be responsible for extra rushers coming free. Jones connected on the first four of those throws and took a hit while he threw an incompletion on the fifth one. Which, again, is a pretty good starting point for a rookie. We told you at the start of camp that this was going to be a real competition. My belief is that it is one, still, and Jones is going to make this call a really tough one for Bill Belichick.

Fields, like Jones, wasn’t fazed by the stage. After the Bears’ preseason game against the Dolphins, Bears beat writers had this exchange with the 11th pick in April’s draft.

Reporter: “Justin, what was it like in your first game, adjusting to that NFL speed?

Fields: “It was actually kind of slow to me, to be honest. I was expecting it to be a little bit faster. But practicing game speed, going at it with my teammates every day, of course, we have a great defense, me going against them every day, it definitely slowed the game up a little bit for me. I felt comfortable out there.”

Reporter: “Did you have any pregame jitters?”

Fields: ‘‘Surprisingly, no. I was as calm as could be, just trying to take it play-by-play, and trying to win every play. Our whole point this week was focus on today, focus on the moment. I was just trying to take it play-by-play.”

Now, it’s not like there’s anything groundbreaking in what Fields said there. But that fact is his sentiment was very much reflected in his play. He had ups and downs, and showed the positives and negatives in his game. So really, the overriding thing the coaches learned in getting to see Fields in live game action for the first time was how calm and collected he was playing, and that showed up in how he kept his eyes downfield and didn’t panic when he escaped the pocket. One such throw happened on a third down in the waning moments of the second quarter, where Fields escaped to his right, pressed the line of scrimmage to draw defenders, then whipped the ball on a line across his body to Justin Hardy for a first down. Another came on a third-and-9 right after the half, in which Fields again scrambled right, drew the defense up, then flipped the ball over a couple of defenders to Rodney Adams for an easy first down. These are examples of the kind of poise, and ability to make it right when it’s wrong, that rookie quarterbacks need to play early. So a good start for Fields.

And really, there was good stuff from all of the first-round rookie QBs this weekend, which is to be expected. This class has long been expected to be a strong one—with Trevor Lawrence, Fields and Trey Lance’s having been known commodities as NFL prospects for well over a year—and that promise was on display this weekend. So with Jones and Fields covered, here are quick hits on the other three.

• Lawrence’s talent was apparent in how natural he looked out there, and how easy difficult throws to the boundaries looked to him. Which is why he’s really been considered the obvious first pick in the draft since he was a college freshman. But watching on Saturday night, I’d say there’s reason to worry about his protection and how much he’ll get hit, especially when you consider he still could stand to put on some weight (he’s acknowledged that offseason shoulder surgery made it tough for him to do that).

• The best thing Zach Wilson did for the Jets on Friday: play conservatively. We’ve seen the wild talent he brings as a freelancing playmaker, but the snaps the coaches were most encouraged by showed Wilson displaying the antithesis of that. On the Jets’ second series, Wilson snapped the ball into a bad call and threw it away to avoid a sack. And later, on a third-and-14, with the rush bearing down, he didn’t try to be a hero, instead checking the ball down to tight end Tyler Kroft, who actually almost got to the sticks on his own. In both cases, Wilson resisted the urge to do too much, and that’s not a small thing for a rookie.

• We saw good and bad from Trey Lance. Everyone saw the 80-yard touchdown—Lance rolled left, then flipped around and threw deep to his right—to 49ers camp star Trent Sherfield. And you probably also saw his impressive poise in finding Charlie Woerner for 34 yards out of his own end zone. But he also took four sacks and nearly threw a couple picks, which, again, underscores part of the deal we mentioned earlier. Going with a rookie will make for ups and downs. And if you’re a contender, it’s a little tougher to sign up for the downs that are inevitable with any rookie.

The Packers showed they could be functional with Jordan Love at quarterback, but he still has a long way to go. The numbers look good: Love finished 12-of-17 for 122 yards and a touchdown, notching a 110.4 passer rating and leading Green Bay to its only touchdown of the night in a half of action. But the consensus I got from those there? He still looks like a rookie, which, to be fair, makes sense, since these were his first NFL game reps of any kind. Among the places where he looks raw …

• He didn’t climb the pocket or take a checkdown on a snap that ended in a strip-sack.

• He stared down receiver Amari Rodgers on the game’s first third down, which allowed for two defensive backs to converge on Rodgers and break the play up.

• He ran the wrong way on another third down.

• Ball placement was off on a handful of throws, and he held the ball too long in spots.

And again, all of this stuff happens for young quarterbacks, and is probably more indicative of how COVID-19 cost him work in 2020 than anything else. But it’s pretty clear, too, why the Packers needed Aaron Rodgers to be the quarterback this year, beyond just wanting to have the reigning MVP on your roster. Now, Love showed a very live arm, and some poise hanging in there through the half. And I don’t doubt Matt LaFleur could make it work with Love if he had to. But this was a long way off from what it looks like with Rodgers.

I don’t know that there’s going to be much change in Deshaun Watson’s situation the next few weeks. Really, whether or not Watson gets moved is going to boil down to whether someone is willing to pay what the sticker price would’ve been in January in a trade, and it’s certainly understandable why, regardless of what or who anyone believes on the 22 lawsuits he’s had filed against him, other teams would be reticent about making such a move. Watson would immediately become the face of the franchise for whichever team he was traded to, and his legal situation would vault to the front page in whatever city that team was located in. Fact is, it’s the sort of move that would require owner sign-off, and with stories like the one our own Jenny Vrentas did this week interviewing two of his accusers continuing to come out, it won’t be easy for a GM or coach to get that. And that’s if even he is comfortable with it. Maybe there’s a GM or coach out there who is, and can get the green light from his boss. For now, though, it feels like if that team was out there, we’d already have seen a deal go down. So my sense is Caserio—who can’t have his first major swing be to trade a 25-year-old franchise quarterback with five years left on his contract for 50 cents on the dollar—is content to wait.

The Steelers’ trade for Joe Schobert is another in a sneaky Pittsburgh trend over the last few years, and one that follows a Baltimore trend. I don’t know if this is an analytics thing (it might be)—but I can say the Ravens have very deliberately mined third-contract types for their roster (Eric Weddle, Calais Campbell, Kevin Zeitler, Sammy Watkins, Earl Thomas, etc., etc.) on the premise that those players are economical and generally reliable, and those signings, as such, have more predictable outcomes. And of late, in bringing in guys like Joe Haden, Trai Turner and Melvin Ingram, it feels to me like the Steelers are following their archrival. Schobert—whom the Steelers landed from the Jaguars for a sixth-round pick—falls into that category and should smoothly fill the void left with Vince Williams’s retirement. The important thing here, to me, is that Pittsburgh has an idea on what it’s going to get, and Schobert should give Pittsburgh a shot to be elite on defense again. And Pittsburgh might need the defense to be that good early on, with the offense’s breaking in an overhauled line.

The Colts have done a great job in building their roster, but they really need to be right on Eric Fisher. Fisher’s not likely to be ready to start the season, and prospective stopgaps Sam Tevi and Julie’n Davenport struggled at left tackle against the Panthers. Now, that doesn’t mean Indy can’t manage it for a month or so at the beginning of the season. But the Colts really need Fisher to be close to the guy he was in Kansas City coming back off his torn Achilles (which is a tough injury to come back from for a big man). With as much as the Colts have invested in the line (Quenton Nelson, Braden Smith, Ryan Kelly), it’d be a shame for the team to be caught at the most important position up front following Anthony Castonzo’s retirement, especially given Carson Wentz’s injury history. This is a big one to watch, for sure.

I like Patrick Mahomes’ level of self-reflection. Good story from Kevin Clark over at The Ringer on Mahomes this week, and in it was this quote from the Chiefs quarterback: “Sometimes, when I get hit early, I don’t trust staying in the pocket and going through my reads. I kind of get back to that backyard-style football a little bit too much. And you could definitely see that in the Super Bowl. I mean, there were times that pockets were clean and I was still scrambling.”

There are a couple of things that I think saying what Mahomes did accomplishes. First, it shows that he’s looking at himself when the rest of the world basically handed him a set of crutches to excuse away the loss to the Bucs with. Lots of guys wouldn’t so openly turn those crutches away. Second, his teammates are going to see that, and know he has their back, and maybe even more so take it as a challenge for everyone to look in the mirror when something goes wrong. Maybe that sounds a little overly dramatic, but I think this stuff counts, and there’s an example from this offseason that explains why. The Chiefs, I’ve heard, were one of the early leaders in COVID-19 vaccination percentage, and most people in that building felt like it happened because Mahomes was an early adopter. “If Pat does it,” one staffer told me, “everyone follows.” And if you look at what he’s said to Clark, it’s pretty clear he’s aware of the power that he has in that way.

I think Hard Knocks needs an overhaul. And really, to me, this is simple. Too many teams are producing Hard Knocks–style content now, and that makes what HBO and NFL Films are doing every summer far less unique. I’m not sure how you fix it. Maybe it’s focusing Hard Knocks on a team’s entire offseason, where there’ll be more stuff to show. Maybe it’s going to what the league has explored, which is programming like what Showtime did with its 24/7 series in college football—where the network would chronicle teams in-season a week at a time. Honestly, I’m not sure exactly what would work. I just know the current Hard Knocks format doesn’t work like it used to. So it’s time to change it.

SIX FROM THE SIDELINE

1) MLB’s Field of Dreams idea was pulled off magnificently. So could something like that happen in football? This week on Twitter, I suggested a Friday night game in Odessa, Texas (the town depicted in Friday Night Lights) as an idea to replicate what baseball did. But then, I know there’s probably no chance that an NFL team is going to walk away from one of 10 home dates it gets annually for a novelty game.

2) Being back in an NFL stadium with fans in it this week was pretty awesome.

3) And over the last couple of weeks, being face-to-face with the people I cover has been great too. Over the last 17 months, we’ve all gotten comfortable, and proficient, in living through Zoom and our phones. My camp trip’s been another reminder to me that being in-person with people is priceless.

4) That the Big 10, Pac-12 and ACC are meeting about forming an alliance, ostensibly to combat the SEC’s landing Texas and Oklahoma, only further bolsters the idea that college football’s going to wind up with about 50 to 60 schools in relevant conferences towering over everyone else. And maybe, eventually, those schools will break from the NCAA and send college sports into chaos (as if it’s not already there).

5) The Woodstock ’99 doc is, to me, a wildly inaccurate depiction of my generation. That festival was a disaster, for sure. But I don’t think it means anything deeper about people who were born in the late ’70s and early ’80s, people who, truth be told, mostly grew up in a peaceful, prosperous time. (In other words, get off my lawn!)

6) I’d really like for people to stop making the pandemic political. I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again—that opinions on everything involving COVID-19 seem to break cleanly along party lines is a really sorry commentary on our country.

BEST OF THE NFL INTERNET

I don’t want to live in a world where this minor level of enthusiasm after steamrolling the entire defense is a 15-yard penalty what’s wrong with you @NFL pic.twitter.com/4kAk3NEkKy

— Warren Sharp (@SharpFootball) August 15, 2021

I agree with Warren here. There should be some level of common sense injected into what’s considered taunting, and hopefully this is just the officials’ working through the new rules emphasis in the preseason.

Bill Belichick to reporters today on whether any of his players suffered "major injuries" against WFT on Thursday night: "I wouldn't tell any player if he's got an injury that it's not major. It's major to him. Career threatening, probably not."

— ProFootballTalk (@ProFootballTalk) August 15, 2021

As Belichick as Belichick gets.

This a grown man hit https://t.co/IfBUQlRiqw

— Footballism (@FootbaIIism) August 14, 2021

Is that a quarterback?

And SoFi is officially an NFL stadium!! (On a serious note, that place is pretty incredible. Big s/o to the Rams for the tour last week.)

Raider Nation showed out tonight. #SEAvsLV #NFLPreseason pic.twitter.com/cXIz3EVRJk

— NFL (@NFL) August 15, 2021

Cool to see these new stadiums finally filled …

Thanks for stopping by @AROD! 👋 pic.twitter.com/BCiWaaghpX

— Las Vegas Raiders (@Raiders) August 15, 2021

… complete with celebrity guests.

Sandro Platzgummer from Austria breaks free for a 48-yard run! #NYJvsNYG #NFLPreseason pic.twitter.com/V4qwBPyOto

— NFL (@NFL) August 15, 2021

Not often you see something like this from my mom’s home country!

WELCOME, TREY LANCE

— Sports Illustrated (@SInow) August 15, 2021

On just his second preseason drive 😱

(via @NFL) pic.twitter.com/Zwh6vp5SJt

Do NOT overreact to this footage.

Old friends catching up. pic.twitter.com/U3eSsh0gVq

— Indianapolis Colts (@Colts) August 13, 2021

After last year, “friends” might be strong, but it’s good to see Carson Wentz and Doug Pederson back around one another.

He’s family ❤️ missed their pregame routine 🥺 #footballisfamily https://t.co/pktmWOe8Vw pic.twitter.com/1TWQObfbjV

— Courtney Rivera (@NFL2Ucla) August 12, 2021

Rivera’s daughter caught this really cool moment on video—and you can see pretty vividly here how much each guy means to the other.

This training camp bond between Cam + Mac ❤️💙 (via @thecheckdown)@CameronNewton | @MacJones_10 | @Patriots

— NFL (@NFL) August 12, 2021

📺: #WASvsNE -- Tonight 7:30pm ET on @nflnetwork pic.twitter.com/PEqo4HZBsB

The last couple of years have shown what a good dude Cam really is. I’m glad everyone’s gotten to see it.

Zo’s brain ... “Has Bob’s head always been that tiny? My God. I could fit three of his heads inside of my head. Wait ... is my head abnormally big????” pic.twitter.com/T4KxVspkGl

— Tom E. Curran (@tomecurran) August 12, 2021

In Zo’s defense, it was roughly 130 degrees at Gillette on Thursday night, so if he was trying to stay still to keep himself from melting on air … good move.

.@PatrickMahomes had to fist bump himself 😅 👊

— SportsCenter (@SportsCenter) August 15, 2021

(via @thecheckdown)pic.twitter.com/cmSVDDPasj

Mahomes wasn’t about to get Brady’d out there.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

I’ll be hitting a few more camps this week as summer begins to wind down. The first set of cuts are Tuesday, which means some minor trades could be coming. And trade talks, as a result of that, will probably start to heat up a little with the final cutdown two weeks away.

We’ll have you covered on that stuff, as we always do, here at the site.

More NFL Coverage:

• Mailbag: How Likely Is a Michael Thomas Trade?

• The Problems with the NFL's Deshaun Watson Investigation

• The Patriots Are Ready for Their Next Quarterback Fairytale

• Josh Allen’s Contract: Strong for the Player but Also Team-Friendly