Business of Football: The NFL Is Losing Its Lawsuit Against St. Louis, But Has Been in Situations Like This Before

These are salad days for the business of NFL owners: Business is booming, with financial prosperity locked in for more than a decade each with their two most important partners. Their labor force is secured with a second consecutive 10-year, owner-friendly collective bargaining agreement. And armed with a labor deal that includes the added inventory of a 17th regular-season game, owners secured media deals totaling a collective $110 billion, with still more to come (Sunday Ticket is still out for bid). And to further amplify their power, this week former Raiders coach Jon Gruden was sacrificed, when his repugnant emails were exposed from a trove of 650,000 emails that certainly included other damaging ones from owners and team executives. NFL owners have simply become very used to winning, which makes it more noticeable that they are on a bit of a losing streak in a court case in St. Louis.

We are almost six years removed from the owners’ decision to relocate the St. Louis Rams to Los Angeles. The NFL, its owners, fans and media have all moved on from St. Louis, with the Rams now a Super Bowl contender in a gleaming new stadium in the country’s second-largest market. The city of St. Louis, however, has not moved on, as those left behind clearly feel they were unfairly and illegally abandoned by the NFL, according to the NFL’s own regulations and policy. And, you know what came next: There were lawyers.

At this point, the St. Louis lawyers are beating the NFL’s lawyers. But there are many rounds to go.

Background

I attended NFL owners’ meetings every year from 1999 to 2008. In several of those meetings, there was an agenda item about placing a team in Los Angeles. Although all stadium sites and financing plans vetted by league administration fell short during that time, the message was clear: There was a strong collective desire to place a team in L.A.; the owners just needed a workable stadium and financing plan.

Fast forward to 2015, and the NFL had not one but two L.A. stadium and financing plans, involving three NFL franchises. The contenders were 1) the Raiders and Chargers, who had joined forces with a stadium and financing plan in Carson, and 2) the Rams, going it alone with a stadium and (private) financing plan, as part of a larger entertainment complex in Inglewood. The issue reached a reckoning at the fateful NFL owners’ meeting in Houston in January ’16, one that I remember vividly, as I was on hand covering it for ESPN.

The key players regarding relocation at that time were the six NFL owners making up what was called the committee on Los Angeles opportunities: Robert Kraft, John Mara, Jerry Richardson, Robert McNair, Clark Hunt and Art Rooney. That group had met several times previously and came to Houston with a recommendation to move forward with the Chargers/Raiders proposal in Carson. There was league-wide empathy for the Chargers’ owners, the Spanos family, who were seen as loyal partners for decades. And despite indifference (and condescension) toward Raiders’ owner Mark Davis (who would later have the last laugh in Las Vegas) all signs pointed to Carson, complete with lobbying from Disney CEO and league partner Robert Iger.

In all my years around the NFL, I can rarely remember when the ownership did not accept the recommendations of the committee leading an issue, whether the competition committee, finance committee or, in this case, the committee on Los Angeles opportunities. Yet it happened with L.A.

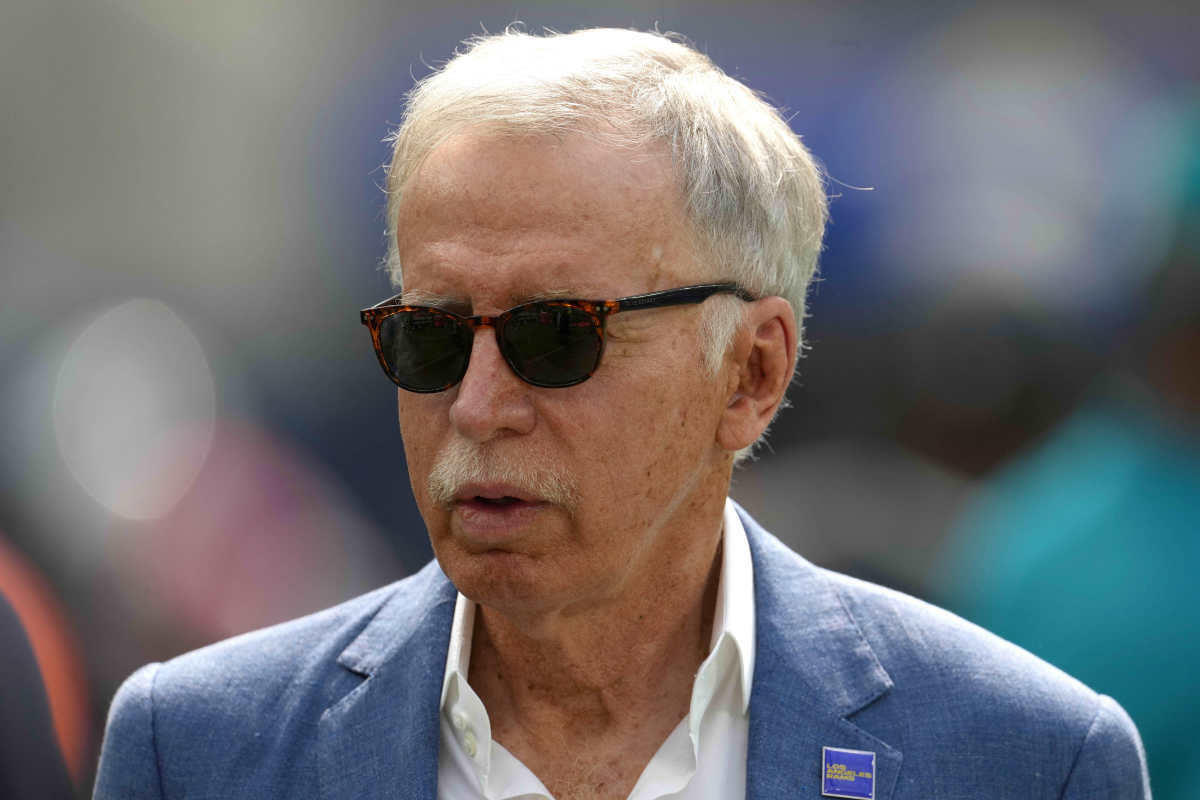

As the meetings transpired, the room shifted. Jerry Jones, with his unabashed gusto and charm, became the advocate for reclusive Rams’ owner Stan Kroenke, who had 1) a net worth over $11 billion, and 2) prime real estate in downtown L.A., purchased years before in a transaction that raised eyebrows in St. Louis. When that happened, Kroenke, of course, wouldn’t comment, and Roger Goodell dismissed it saying, and I’m paraphrasing: Stan buys real estate all over the world; this is no big deal. Well, of course, it turned out to be a pretty big deal for the future of the Rams.

Jones sold a vision for “NFL West”—in downtown L.A., not suburban Carson—hosting not only NFL games but NFL offices, NFL Network, the draft, the combine, the Olympics and multiple other big events. The Rams won the L.A. sweepstakes, sending the Chargers and Raiders back to their local governments which, of course, neither of them would ever do business with again.

In covering those meetings, I was struck by the fact that there was little, if any, talk about whether the NFL’s established relocation policy was satisfied. The clear feeling from Goodell and ownership was that whatever St. Louis (or San Diego or Oakland) had done to keep their teams from moving was not enough to satisfy the policy. It was noted that in 2015, the St. Louis lease in the Edward Jones Dome had converted to a year-to-year proposition after it was not considered among the top 25% of NFL stadiums. This measure, which made St. Louis a free agent, could be interpreted as either St. Louis’s not doing what was necessary to keep the team there or—as St. Louis would later argue—Kroenke’s not putting in the effort to maintain the St. Louis facility, as he had his sights set on Inglewood. The NFL clearly feels it was the former.

The cities left behind left those Houston meetings with their tails between their legs, but they were not done. The city of Oakland later sued, albeit unsuccessfully. St. Louis sued as well, and to this point, it has had more success than Oakland. We are in Year 4 of that litigation, one that has seen recent successes against Kroenke and the NFL.

What the suit alleges

The city of St. Louis—along with St. Louis County, and the St. Louis Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority (I will refer to all of them here as “St. Louis”)—sued NFL owners in 2017 with a kitchen sink full of legal claims: breach of contract, fraud, illegal enrichment and tortious interference, all resulting in substantial financial losses for the city of St. Louis. The suit has been in the City of St. Louis Circuit Court (22nd judicial circuit).

The basis of the suit, from my reading, is that the NFL owners breached an enforceable contract among themselves in the relocation of the Rams to L.A., a breach to which St. Louis is a third-party beneficiary, by not complying with their own relocation policy guidelines (the “Policy”). The through line of the plaintiff’s argument is that despite the fact that St. Louis met the contractual guidelines and protocols of the Policy, the owners disregarded the Policy when it stood in their way of their desired result: getting the Rams to LA.

St. Louis alleges that the assurances from the NFL misled them into believing that the city had a chance to keep the Rams while it was, at the same time, facilitating the Rams’ relocation to L.A. St. Louis also argues that the NFL did not—as the Policy mandates—provide an adequate opportunity for interested parties to offer written and oral comments, scheduling a public hearing months before the Rams actually petitioned the NFL to relocate.

The NFL, of course, has denied these allegations and argued that its statements, both in public and private, are not legally binding. It has argued, and will argue, that its business practices, as unsavory as they may seem to some, are, well, how the business of football works. The owners argue that they did comply with the Policy and the law, even if it left a hurt and damaged St. Louis in its wake.

The damages claim

Not surprisingly, the two sides see potential damages from this case in completely different worlds.

St. Louis has requested “at least $1 billion” in damages. It claims that the lost tax revenue—hotel, property, sales, ticket, etc.—exceeds $100 million. Further, the city claims disgorgement: that the $550 million relocation fee the Rams paid to other owners should be disgorged and given to St. Louis. And it claims entitlement to a share of the increased valuation of the franchise since the move to L.A. (the Rams are now valued at $4.8 billion by Forbes, the fourth-highest valuation among NFL teams). St. Louis will present everything it can to a jury here—more on the jury issue below—including a request for punitive damages that could bring the total ask into the billions.

The NFL, of course, views disgorgement of the relocation fee and increased franchise value as legally unsupportable. The only damages that it seems the league would consider at this point—as a potential settlement—appear to be out-of-pocket expenditures in the $50–$100 million range.

Where the case stands

Over the past four years, the NFL has resorted to a familiar legal strategy for large corporations: Delay, delay, delay. In the midst of these delays, the owners have lost motion after motion, including a request to have the case moved to private arbitration and repeated requests to have the case moved out of St. Louis, where they can expect an unfriendly jury (again, more on this below).

The NFL also recently filed motion for summary judgement (to have the case thrown out). The judge overseeing the case, Judge Christopher McGraugh, denied the motion, opining that the NFL had treated the Policy as binding in the past, pointing to Commissioner Goodell’s previous deposition testimony that the league’s relocation guidelines were “mandatory.” McGraugh further noted that even though St. Louis was aware of Kroenke’s desire to relocate, the city still had reason to anticipate “a probable future business relationship that gives rise to a reasonable expectancy of financial benefit.”

The NFL has now filed another petition to move the case out of St. Louis, this with the Missouri Court of Appeals. That court has asked St. Louis to respond, giving the NFL a glimmer of hope about an important issue that could reappear on appeal again after jury selection begins.

And just last week, according to sports lawyer Dan Wallach—who has done great work covering this case—the NFL filed a motion to bifurcate the upcoming trial. If granted, this would have the case go forward only on the issue of liability. Then, if St. Louis was successful on the liability issue, a second trial would be held on the issue of damages.

“Show us your books!” “No.”

We are in the discovery phase of the case now, as we approach a potential trial date of Jan. 10. And the discovery information in which St. Louis seems most interested is personal financial information from owners, especially a few—Clark Hunt, Jerry Jones, Robert Kraft and John Mara—who have been noncompliant with that request (it is unclear whether other owners have been forthcoming with such information or if it simply was not requested). Thus, last week St. Louis filed a motion for sanctions due to non-compliance, with a hearing to take place on that issue Wednesday.

The NFL’s decision to ignore the request for financial information is certainly on brand. Having covered multiple collective bargaining negotiations between the NFL and NFLPA, when asked to show their books, the consistent answer from ownership has been No and the union has been unable to force it. Indeed, the only information we have about team finances is that of my former team, the Packers, who must—as a public corporation—provide an annual financial report. As far as I know, there have been no successful litigation requests to have NFL owners show their books and—pardon the pun—the jury is still out on whether we will see that here.

Losing now but been here before

St. Louis is certainly winning the early stages of this four-year fight with the owners, and some covering this story—which notably does not include NFL Network nor ESPN—have suggested this case could 1) cost owners billions of dollars, suggesting the disgorgement and increase in valuation theories could succeed, and/or 2) perhaps even compel NFL owners to grant St. Louis an expansion franchise. To this I say: Let’s hold the phone.

The NFL has been in this position before (and will likely be here again): on the losing end of a court decision that could 1) change the way it does business, and 2) cost it, potentially, billions of dollars. But that has now happened thanks to the appellate courts. I point to three examples:

Draft eligibility

In 2013, Maurice Clarett challenged the NFL’s draft eligibility rule requiring a player to be three years removed from high school, a rule particularly disadvantageous to running backs like him. Amazingly, Clarett won at the lower court level, bringing panic to the NFL scouting community. I remember our scouts’ lining up at my door asking if we now had to scout college sophomores, freshmen and even high school players! I told them what the NFL lawyers were telling me: Relax, we’ll win at the next level. And they were right.

The 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, in an opinion written by future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, overruled the lower court, and the NFL draft eligibility rules stayed intact.

Lockout bargaining

The NFL locked out its players in 2011, in order to gain leverage in negotiating a new collective bargaining agreement, knowing the NFLPA could not negotiate as firmly without checks coming in the door. The union litigated the matter and won in lower court. The NFL appealed, and won, as the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals allowed the lockout to continue, forcing the union to negotiate a harried, team-friendly CBA as training camps opened.

Commissioner power

Tom Brady took his four-game Deflategate suspension to court in 2015 and won. The NFL, of course, appealed, and won. The 2nd Circuit restored the suspension and affirmed commissioner power over the players.

The point of these three cases is that the NFL has been here before: lower court rulings that threatened hallmarks of NFL power: draft structure, labor negotiations and commissioner power. Through appellate courts and lawyers, owners have consistently restored order to their management-tilted business model.

Could this situation be different? Well, perhaps, but I don’t think owners are quaking in their boots over it.

Maybe discovery requests will show that the owners, so anxious to get to L.A. after a 20-year drought in that seductive market, cut corners, ignored protocols and breached their internal contract and Policy at the expense of St. Louis.

Maybe a biased St. Louis jury will award reams of money to the city of St. Louis, taking a small bite out of the net worth of Kroenke and/or perhaps other owners (although he will likely indemnify others for their losses).

If either of the above does happen in time, that time is not near. There are months before a scheduled trial date in January, assuming it is not delayed. And if there is a decision that goes against the league, the NFL will of course appeal to a friendlier forum, continuing to make the case of a biased jury along the way.

Through it all, the only constant here is my mantra: There will be (well-paid) lawyers.

Grab a Snickers bar; we’re going to be following the St. Louis litigation for a while.

More NFL coverage: