Rhapsody in Blah

Two Latin words, medius (“middle”) and ocris (“mountain”), joined hands in the 16th century to make a new word—mediocre—that described anything of middling stature: neither peak nor valley, neither tall nor short, neither Manute Bol nor Muggsy Bogues. Most of us reside there, between Mount Everest and the Marianas Trench, in the safer elevations of mediocrity.

Sports are meant to be deliverance from all that, with their built-in extremes, their binary heroes and GOATs, the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat. Win or lose, you will feel something, unless of course you draw. But a tie is a small sample size, of little statistical meaning. For sustained mediocrity, achieved over an entire year, there is only the sister-kissing marathon of the .500 season.

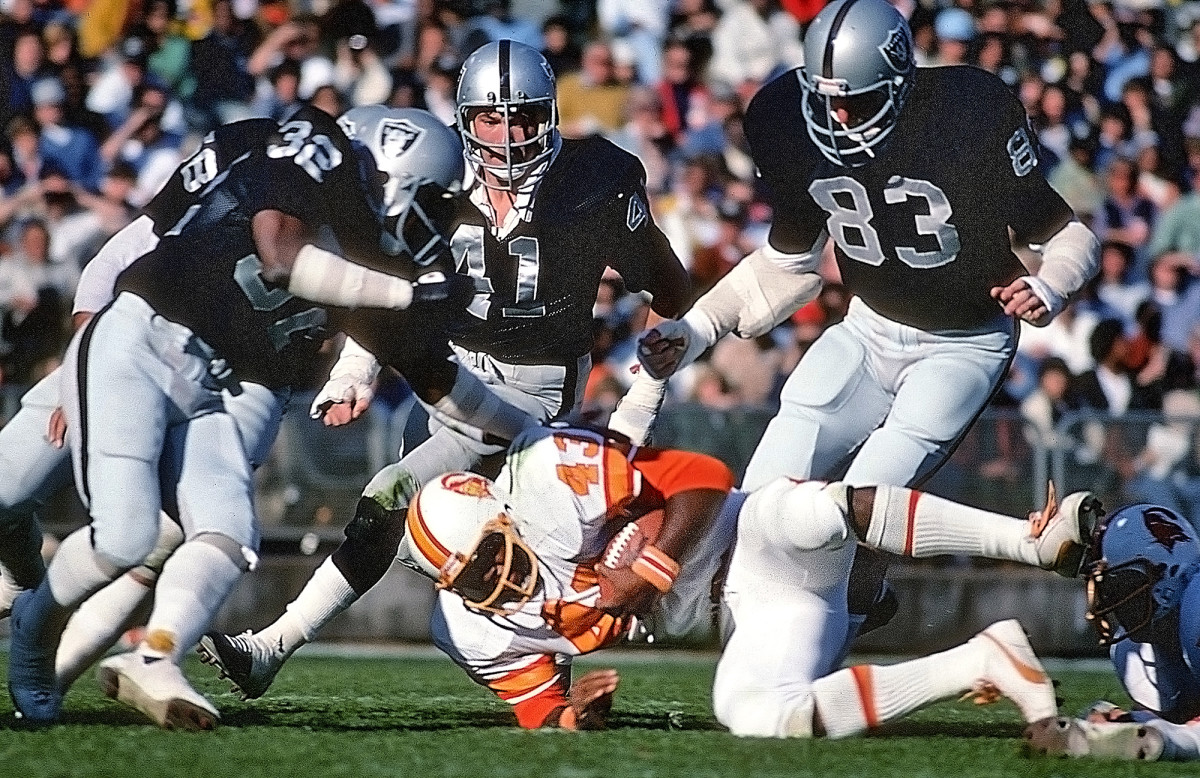

“Nobody wants a .500 record,” Browns wide receiver Clarence Weathers said in 1985, when Cleveland finished 8–8. And now that the NFL schedule has manspread to 17 games, no team in that league will have to go 8–8 again (though a team truly dedicated to mediocrity may yet go 8-8-1). Let the Raiders claim a Commitment to Excellence; 8-8-1 will require a Commitment to Meh. Those 8–8 Browns of ’85 made the playoffs and promptly lost to the Dolphins to finish 8–9, proving Weathers’s point that nobody who can possibly avoid it wants a winning percentage of .500.

“We’re not a great team,” Dolphins guard Roy Foster told the Miami Herald after seven games into the 1989 season, “but we’re not an 8–8 team.” That Miami team finished 8–8 and served, for fans, as a 16-week sensory-deprivation chamber. If you’ve forgotten the ’89 Dolphins but remember the ’72 Dolphins who went undefeated—or the ’76 Buccaneers who went winless—that’s because history regards the great and the terrible but forgets the mass in the middle. Peter the Great and Ivan the Terrible echo down the ages; no one builds monuments to Dale the Unremarkable.

Perhaps we should. In baseball, the Angels have been a Rhapsody in Blah. The team had an all-time winning percentage of .499 coming into this season, its 61st, and predictably hovered around .500 for most of 2021. The two best players in the game, Shohei Ohtani and Mike Trout, make no difference to their .500 mojo. If the Angels were a ride at nearby Disneyland, they would be neither the Matterhorn nor the Submarine Voyage, but something comfortably in between, keeping fans safe from both altitude sickness and the bends.

In 1986, his first season as a head coach in the NFL, Buddy Ryan witnessed a game of historic ineptitude between his Eagles and the St. Louis Cardinals. The teams combined to miss three game-winning field goals in overtime, which ended in a 10–10 draw. Ryan would be coach for 111 games over seven years and retire with a regular-season record of 55-55-1. That tie forever placed him in the company of knuckleballer Charlie Hough (216–216 lifetime record); Daniel Day-Lewis and Frances McDormand (both of whom are 3–3 lifetime in acting Oscars); and the Trappist monk and spiritual seeker Thomas Merton, who wrote, “We cannot be happy if we expect to live all the time at the highest peak of intensity. Happiness is not a matter of intensity but of balance.”

By summer 2020, Rafael Nadal had played 2,612 games against Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic combined. The Spaniard had won 1,306 of them and lost 1,306 of them, at which point the three greatest men’s tennis players ever, indisputably at a stalemate, should have just agreed to disagree.

“If you look at my overall career,” Roger Craig said upon his retirement in 1992 after 37 years as a player, coach and manager in the big leagues, “I’m going out a winner.” That can’t be said of Charley Winner, who was 44-44-5 as coach of the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals and the Jets, but it is true of Craig, who went 738–737 over 10 seasons managing the Padres and Giants. Career records turn on bad hops and seeing-eye singles. NHL goalie Nikolai Khabibulin won 333 games over 18 seasons but lost 334, his record besmirched by a single puck. Puck, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, said, “What fools these mortals be,” and it’s true: Only a simpleton would reduce a life’s work to a winning percentage.

The person who goes .500 in life, after all, has had a good run. Wilbert Robinson won the last two games of the 1931 season with the Brooklyn Robins, upping his lifetime managerial record to 1,399–1,398, after which he retired, triumphant. He died three years later, of a brain hemorrhage, after falling in his hotel room, but not before asking a reporter to “make a funny story about it. Say your Uncle Wilbert slipped on a banana peel.” This was a man who knew, as Monty Python did, that life is “all a show, keep ’em laughing as you go.”

Around every corner lies a banana peel. Ask the 1982 Padres. They went 81–81 that year but left unfinished business. In ’83, San Diego became the five-hundredest team in sports history, going 81–81 again, but this time scoring 653 runs while allowing 653.

Those Padres may have seemed to be running in place, exhausting themselves on the Great Hamster Wheel of Futility, but they were really moving forward. In 1984 they won the NL while wearing sleeve patches to commemorate owner Ray Kroc, who died that year, the same year the company he founded—McDonald’s—launched the McDLT, which was both a sandwich and a metaphor.

The McDLT was a hamburger served in a segregated clam box, with the steaming patty in one compartment and the crisp lettuce and tomato in the other. “Keep the hot side hot, and the cool side cool,” went its advertising slogan, for the McDLT acknowledged what sports fans already knew. We have a taste for things piping hot. We enjoy things that are freezing cold. But our dull palates cannot abide, nor scarcely even remember, the tepid, room-temp, lukewarm in between.

See Also:

• Inside the Quest to Prolong Athletic Immortality

• NFL Coaches Are Changing the Way They Talk About Fourth Down

• Don't Count Out the Clippers