After the Tree of Life Shooting, He Wanted to Help—So He ‘Just Started Doodling’

Excerpted from Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood by Mark Oppenheimer. Copyright © 2021 by Mark Oppenheimer. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Pittsburgh is known for two big things, and both of them live squarely in the past. It was once the greatest football city in the land, with four Steelers Super Bowl wins in six years—and what teams those were, in the 1970s, with Terry Bradshaw and Lynn Swan, and Franco Harris’s immaculate reception; big showtime teams of muscle and destiny. And Pittsburgh had the industry that gave that football team its name, its identity, even its logo: steel. Then the football teams became mortal, and the steel industry left. The city built at the meeting of three rivers is now a hub for medicine and computer science—few cities have more robotics experts per capita—but now it feels smaller, less like a place where big things can happen.

Three years ago, though, a very big thing happened, right at the time of year when a city wants big things from its football team, or a baseball team very late into a playoff run. Nothing like that was coming on October 27, 2018, the Saturday morning when a man entered the Tree of Life synagogue building, on the corner of Shady and Wilkins avenues in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood, and shot dead 11 Jews. Tree of Life, as the crime was to be known—some mass killings take on city names, like Parkland, while others get building names, like Pulse Nightclub or Sandy Hook—was to be the deadliest antisemitic slaughter in American history. Pittsburgh, a historically tolerant city, where fans in yarmulkes and turbans cheer loudly for the same black-and-yellow-clad teams alongside their Christian neighbors, now had a new, terrible distinction.

The morning of the shooting, a graphic designer named Tim Hindes and Robert Bowers, the alleged shooter, both left their homes south of Pittsburgh and drove north, across the Monongahela River, into town. The shooter went all the way to Squirrel Hill; Hindes went to Greenfield, the neighborhood just south, to help a friend move. He was about a mile from Tree of Life.

When Hindes, then 40, was driving home, he began getting text alerts about the shooting. As it happened, he had been thinking about antisemitism lately: A close Jewish friend had just that week been the target of some antisemitic remarks, and Hindes was wondering what he, as a non-Jew, could do to help. “I had struggled with knowing the right thing to do, to say, and ended up not saying anything,” he said.

Hindes thus felt especially determined to take action. He got home, turned on the news, and fired up his desktop Mac. “I just started doodling,” he said. Within 10 minutes, he had decided on two design elements that would form the heart of whatever his final design would be: a Star of David, the iconic Jewish symbol; and a hypocycloid.

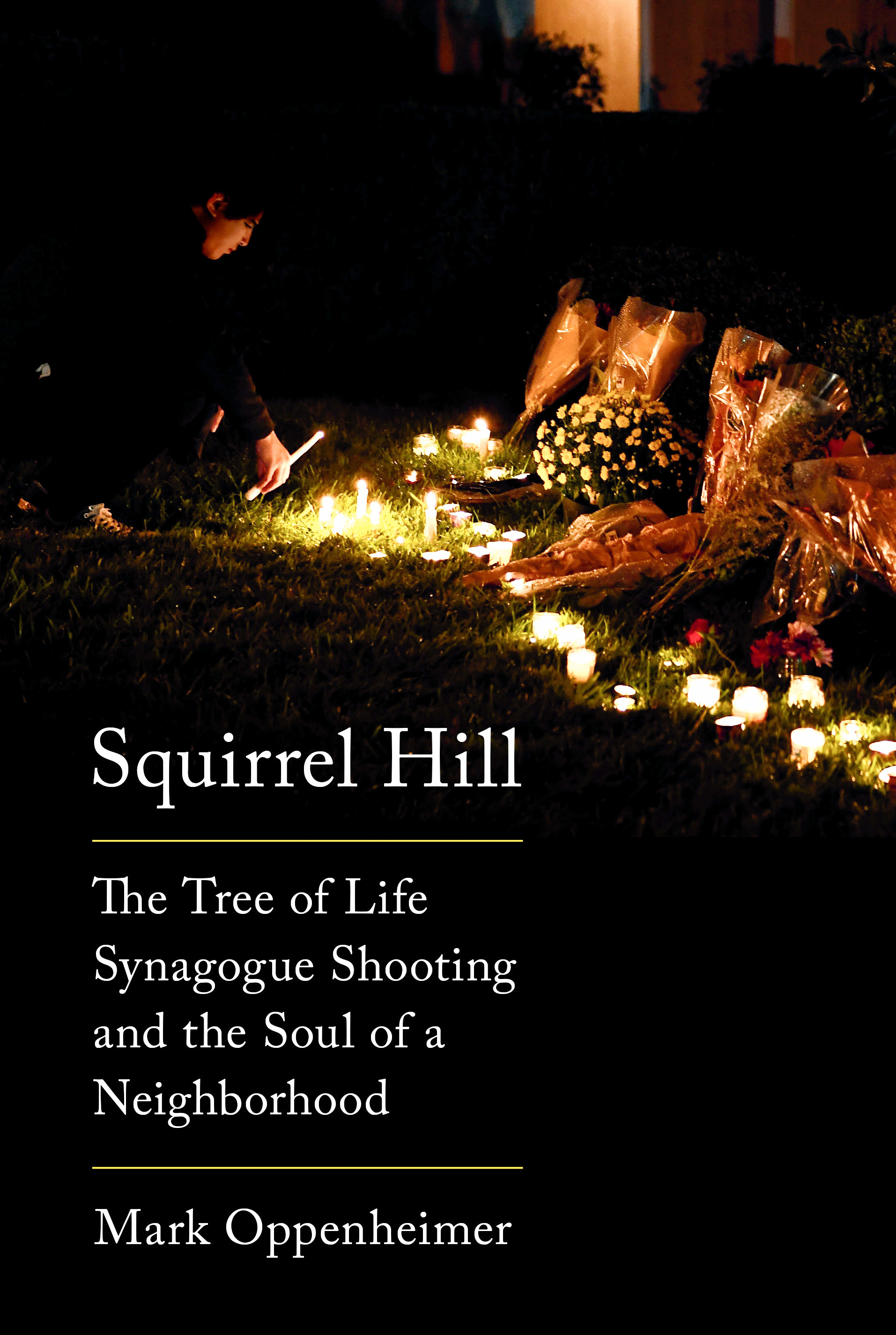

Buy Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood

Geometrically speaking, a hypocycloid is a curve traced by a point on the circumference of one circle, inside another circle, rolling internally on the circumference of the larger circle. But Pittsburgh-wise, and football-wise, the hypocycloid is the universally known symbol of the Steelers. Their logo, found only on the right side of a player’s helmet, contains four elements, arranged in a diamond: The left point is the word Steelers, while the top, right and bottom points are, respectively, yellow, red and blue hypocycloids. Old-time Pittsburghers know that the logo, adopted in 1962, is based on a design by U.S. Steel, later adopted by the entire industry, meant to represent domestic steel in its battle—which it lost—with foreign imports. The three hypocycloids (to be precise, they are astroids, or hypocycloids with four cusps—diamond-like hypocycloids) thus carry the banner of local pride as remembered in two lost glories. After that ’70s stretch, the Steelers have won twice in 40-odd years.

The six-pointed Star of David, known in Hebrew as the Magen David, or Shield of David, was not originally Jewish. It is found nowhere in the Hebrew Bible or in the Talmud. It was used decoratively by many peoples for hundreds of years. During the Renaissance, it began to proliferate as a design element in Jewish books and on Jewish flags and buildings. But only after 1897, when it was used as a symbol for the First Zionist Congress, did world Jewry come to embrace the Star of David, and only after it appeared on the flag of Israel, in 1948, did the world come to know it as Jewish.

Hindes fiddled around with his two basic images, playing with color, size and placement, putting a Star of David up top. He liked where this was going. But the word Steelers had to go. “In thinking through the words, I actually thought of Boston and Boston Strong, and of Orlando Strong. You see those ‘strong’ things whenever a tragedy happens. It seemed too common and monotonous. Pittsburgh is different. It’s not like any other city. It needed a different message.” He decided on the motto Stronger than hate to replace Steelers as the left-side element of his design.

Hindes had no big plans for what he’d drawn up. It was just a way to feel like he was doing something. He posted the image to his private Facebook page. A couple of friends liked it and asked if he would make the post public, so that they could share it. He said sure, why not, and changed the post’s status. He got up from his computer, stretched his legs, walked about the house for a bit. When he returned to his computer a few minutes later, the post had 500 shares. Then 1,000. Then 1,500. By the end of the day, friends had seen it on Twitter. It was going crazy.

The next day, Sunday, Hindes realized, somewhat sheepishly, that he had created the iconic image of the Tree of Life shooting. It was seen on banners at the Steelers game that day. The actor Michael Keaton, who grew up near Pittsburgh, shared it on Instagram. People who would never be able to name any of the victims, who wouldn’t recognize the synagogue’s façade if they drove by it, would know the crime by Hindes’s smart, succinct visual. He decided to make it clear that he was giving it away for free. “I said: This isn’t mine anymore; this is Pittsburgh’s. This is everyone’s. So I posted a link to a quick survey online, where people could say, I promise to use it for good, not evil.” He also asked people to click a box promising that any money they raised with the image—say, by selling T-shirts—would go to victims’ funds. He had no way to enforce any of this, but it was the gesture he wanted to make. When visitors to the website responded affirmatively, they got a high-resolution copy of the image emailed to them.

By Sunday evening, the image was in front yards, on doors and in storefront windows up and down Forbes and Murray avenues in Squirrel Hill. On Facebook and on Twitter, it replaced people’s faces as their avatars. The simple image proclaimed so much. The words Stronger than hate shouted out to victims in Boston, Orlando and elsewhere, saying both We remember and Us, too. At first glance, you could miss the substitution of the Star of David as the yellow hypocycloid and think you were just looking at the Steelers logo—and that made the second-glance recognition so metaphorically striking: The Jews are a part of the whole, seamlessly integrated but holding on to their own identity. Fitting in but standing out.

For their part, the Steelers showed up for the Jews in the aftermath of the killing. Michele Rosenthal, whose two intellectually disabled brothers were among the 11 murdered at Tree of Life, had worked in the team’s press office for years, so in the clubhouse the deaths felt personal, not far away. Numerous Steelers, including quarterback Ben Roethlisberger (who later wore Hindes's logo on his cleats) and coach Mike Tomlin, and old veterans like Harris, attended Cecil and David Rosenthal’s joint funeral on the Tuesday after the shooting. Former defensive lineman Brett Keisel was a pallbearer.

The team’s close relationship with the victims made it fitting that Hindes gave them merchandising rights to the design. Later in the week after the shooting, according to Hindes, “the Steelers reached out to me and said, ‘Hey, we are getting all these requests; people think it’s our symbol—would you be willing to sign over merchandising rights to us, and you maintain design rights?’ ” Hindes agreed, on the condition that any money the team raised with merchandising be given to the victims’ funds or to anti-hate groups.

Hindes never expected his work to become associated with Jews or Judaism. “I’m Lutheran,” he said. “My heritage is German. I was definitely raised in a churchgoing family. I have gotten away from it recently a little bit, for a number of reasons. It was mostly around the election”—Donald Trump’s election, in 2016—“and really trying to stand up for your ideals and beliefs that made me wane away from it. It doesn’t mean I don’t have faith.” He tends to feel his faith most deeply in nature. “I am an avid outdoorsman, so I tend to use that as my outlet for my appreciation of the world and greater being. Hiking, kayaking, camping…” Still, as much time as he spends in the hills outside the city limits, he thinks of himself as a native son. “I grew up in Pittsburgh. I never left. I love it too much to leave. It’s my city and, God willing, I’ll be here forever.”

You can still see Hindes’s design everywhere in Pittsburgh, above all in the stands at sporting events. Black with a little splash of yellow, it blends in easily with all the other Pittsburgh fan gear. The logo also works well on a yarmulke, the small skullcap worn by religious Jewish men, as I discovered in December 2018, when I attended a bar mitzvah at Tree of Life (in its temporary space, rented from a nearby synagogue). There were several Stronger than hate yarmulkes that morning. One of them was near the front of the room, atop a full, beautiful head of wavy white hair. Something about that head looked familiar, and I realized before long it belonged to Robert Kraft, owner of the Patriots, who were in town to play the Steelers the next day. Kraft had come to pay his respects to Tree of Life, and to give the bar mitzvah boy’s family a special present. The 13-year-old ended up with tickets to the game, while I got a blurry photograph of the Patriots’ owner wearing, essentially, Steelers garb—a testament to the power of this unusual design, and a reminder that even the fiercest competitors know when something more important than a rivalry is at stake.

• Colt Brennan: ‘They Did Everything, But Nothing Could Ever Save Him’

• Karl Anthony Towns Opens Up About His Season of Grief

• Inside the Quest To Prolong Athletic Mortality