Arts and Crafts, Belichick-Style

As the son of a coach, and a lifelong football devotee, Brian Ferentz figured he could handle every possible expectation that came with his new job as a low-level offensive assistant in New England. He would live the Patriots’ infamous 20/20 coaching existence, working up to 20 hours a day, for about $20,000 a year. He knew he would become an anonymous cog in a high-functioning machine, spending his days—and most nights—swamped in grunt work while receiving little credit for his toiling. But he also knew he had gained entry to a coaching laboratory that could change the trajectory of his life, starting in 2009.

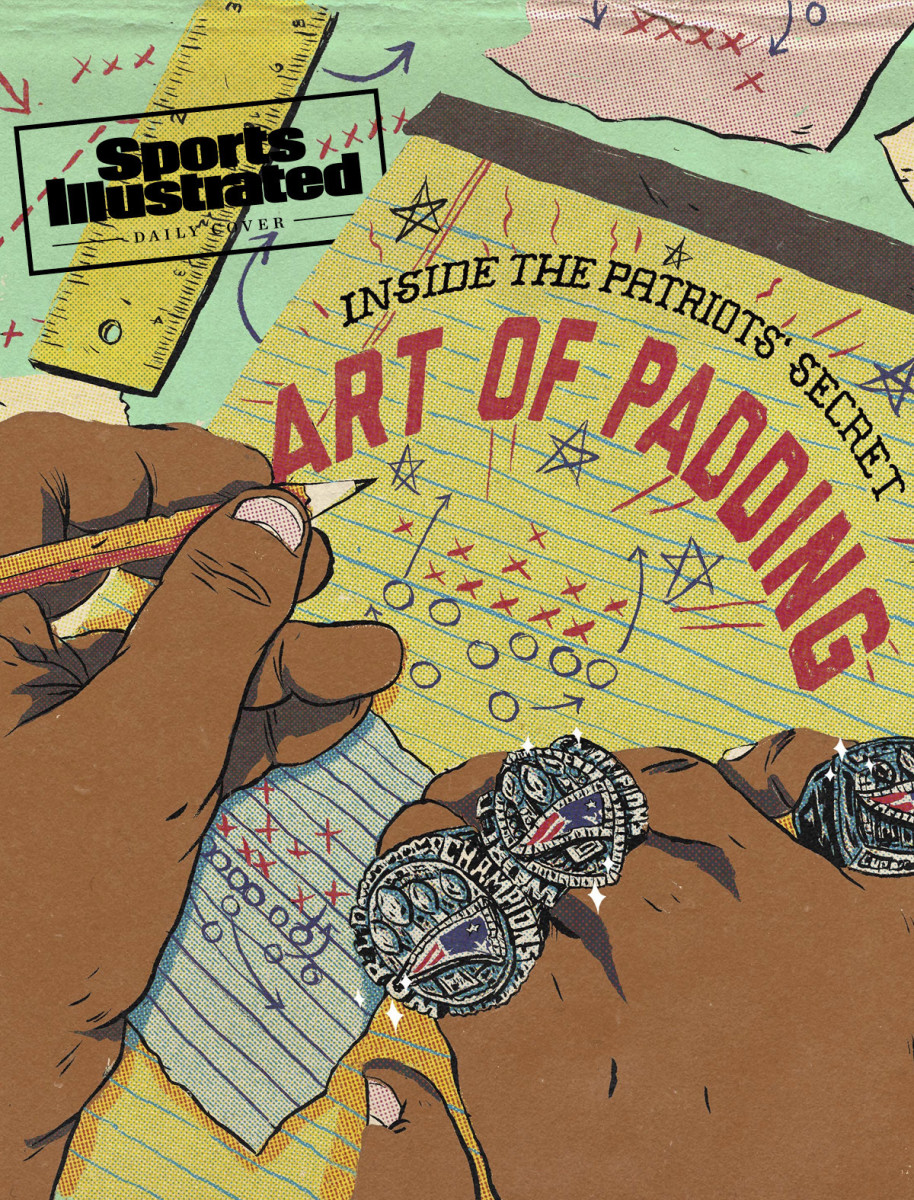

He expected it would be hard. He didn’t expect … an art project? But the team assigned him the NFL equivalent of one, immediately. Bill Belichick summoned Ferentz to his office, where he’d school him on one particular—and particularly tedious—process that New England emphasized more than any other team. Belichick called it “padding,” his method of diagramming plays from opponents. It served to gauge football knowledge, inform game plans and teach the nuances of an infinitely complex sport—part torture chamber, part proving ground, part barrier to entry and part football seminar all wrapped into one exercise.

Every NFL team charts its opposition, on some level, to varying degrees. And other coaches, like Bill Parcells, made their entry-level assistants pad. But while those familiar with the process claim not to know its origin—whether it started with Parcells; Belichick; Belichick’s father, Steve; top-secret Patriots assistant Ernie Adams; or elsewhere—all agree that no one embraced the method, or gleaned more value from it, than Belichick himself.

Ferentz understood the extent immediately. Two words popped into his mind: “holy” and “s---.” A man who once considered himself ready for every nuance of the job was now doubting whether he could do it. He would scour film of upcoming opponents and diagram their offensive plays in staggering detail, then take those diagrams, cut them out, place them into booklets and hand them over for review. Some games took eight hours, depending on the number of plays and the complexity of the scheme, while others could be completed in closer to four. With four or five games to review each week, his mass of other responsibilities and actual coaching, he started to add up the math for a 17-week season, only to stop because he had to pad again.

The “pads” were sheets of paper, 8½ x 11 inches, with a horizontal line dividing the page. They sketched one diagram on top and the other on the bottom. The assistants filled in four plays on each sheet by using both sides. They noted the down and distance; field position, quarter and time remaining; numbers for each of the 22 players and their assignments.

Ferentz’s initial attempts looked like hieroglyphic markings etched in a forgotten cave. Lines everywhere. None straight. Revisions. Crossed-out revisions. Revisions on top of revisions. The method was meant to yield clarity, but he had turned it into utter, disastrous confusion. After several weeks spent padding for the defensive staff, Ferentz transitioned to a different role. He saw even the drudgery inherent in his new position—lowly offensive assistant—as “a blessing”; it meant he would no longer have to pad.

Thirteen years later, Ferentz is Iowa’s offensive coordinator. He’s still a coach, and one who never expected to embrace that “miserable, terrible, awful” process that once forced him to question both his chosen profession and, at times, his existence. Instead, he came to view one specific process, from all of New England’s myriad approaches, as the primary element that built the nebulous, mystical aura known as the Patriot Way.

He’s now a padding proponent. Lifetime membership.

Dante Scarnecchia coached football for almost half a century, spending 34 of those seasons in New England. Few came to understand the genius of Belichick better, specifically, the intention drilled deep into methods that could seem insignificant, or overwrought. Even fewer padded with Belichick himself.

Funny story, says Scarnecchia, now retired and trying to forget his padding apprenticeship. In 1993, Bill Parcells took over in New England, and when he interviewed Scarnecchia, he had but one job open. If Scarnecchia wanted to stay with the team, he could become a defensive assistant, back at the bottom despite decades of experience. His title meant “doing all the breakdowns.”

“Absolutely,” Scarnecchia responded. “I’ll take it.”

His foray into the padding universe started then. Same as it had for Ozzie Newsome, Phil Savage and Pat Hill in Cleveland. Same as it would for Matt Patricia, Brian Flores, Patrick Graham and others years later in New England, a few dozen assistants in total. Newsome calls their group a “small fraternity,” albeit a weary one, and it includes Belichick, once an assistant to Parcells.

When Belichick took over in New England (2000), he transformed the coaches’ offices into a kindergarten classroom. Desks were stocked with notepads (white, yellow), pencils (always Ticonderoga, No. 2), rulers, erasers (always white), scissors and Scotch tape.

The padders watched all-22 game film for their diagramming. They made sure to station a remote nearby, although they wore “rewind” buttons thin. The sketches they were expected to create contained far more detail than the basics, a level beyond any other charting process in the NFL. They wrote the receiver splits (down to the inch); the route depth; the distance between tailback and quarterback; protection schemes; defensive alignments, stunts, and disguises; and whether D-linemen were slanting (to attack) or shading (to disguise). They detailed relevant tendencies of opponents above the diagram, along with other observations (how linemen accidentally gave away clues based on, say, foot positioning), ideas (perceived strengths, weaknesses) or notes (why the time of game influenced a decision). Then they cut out each and taped it inside, and placed completed pages into a three-ring binder.

The key, for Belichick, and hence for all of them, was consistency, which required high levels of both understanding and memorization. If they called a play “Zero Out Slot” one week, they needed to call the same play the same thing the next. To alleviate any confusion, the padders referred to The Cookbook, a three-ring binder that contained diagrams and names for every formation, pass route and run play. If they found a better name, or made a more accurate diagram, they would swap that version in. The Cookbook became both a Belichick blueprint for how the Patriots saw football—and the most elaborate collection of recipes in sports. “So we could all see the game through one set of eyes,” Scarnecchia says.

Padding became so central to the Patriot Way that Belichick started to put job applicants in rooms with all the necessary tools to prove their aptitude. With minimal instruction, they padded. But the coaches were not interested in new information, necessarily. They were interested in how those applicants processed info. How long did it take them? What did they see? How revealing were their diagrams? How exact?

When the Patriots coaches/interviewers returned to those rooms, they asked a million questions about the methodology employed, transforming a typical job interview—what’s your greatest weakness?—into an X’s-and-O’s interrogation. Which helps explain how a hopeful with an aeronautical engineering degree (Patricia) and a graduate from Belichick’s intellectual alma mater (Eric Mangini, Wesleyan), ended up on staff.

Such is the beauty of the pad.

The assistants swapped “sleep” for catnaps, taking turns and jostling one another awake. They diagrammed on the team bus as it departed stadiums, on flights home from away games, early in the morning over coffee, frantically during lunch and through exhaustive late nights. In other words, they padded every day, everywhere, lest they fall behind.

They even traveled with makeshift padding kits, their suitcases stuffed with pencil sharpeners (electric, ideally), packs of erasers, legal pads and boxes of Ticonderoga No. 2s. Like, Ferentz says, “we’re in sixth grade.” They also hunted local office supply stores in search of the rare six-inch ruler that would fit perfectly on half a page. That way they could draw straight lines. When theirs broke, or went missing, they used credit cards or hotel room keys. “You had to bring a duffel bag with [everything] in there,” Ferentz adds. “But you couldn’t go anywhere without it.”

In the interest of time management, they prayed to the padding gods for shorter games, with fewer offensive plays, for their upcoming opponents. They’d scour their own schedule before each season, hoping for opponents with simpler offenses and teams that ran the ball often, because more runs meant fewer clock stoppages, and fewer clock stoppages meant fewer plays. Most teams averaged about 60 plays a game. When they had only 50 diagrams to draw, it felt like Christmas morning. On weeks when they had 80, it felt like being banished to a special kind of dungeon, the lone task: scribbling out football plays every second they were awake.

To describe this process as simply “time-consuming” is an understatement. It’s more soul-crushing than that. Which is why, even though Scarnecchia sees the value, he also still refers to it as “the job from hell.”

“If you’re not the first guy in and the last to leave, you’re probably not doing it well,” he says.

No one ever mastered padding, according to those who tried. But if they did well, if their pad sparked an idea Belichick implemented into a game plan or deployed to shift momentum in a game, even Super Bowls, they were promoted. When assistants moved up the coaching hierarchy, the bigger paycheck was nice but not as sweet as being able to switch from creating pads to reviewing them. Most padded for a handful of weeks, or all of one season. The ones stuck in the process for multiple years certainly improved their speed in lockstep with better understanding, a deeper knowledge base and days lost to repetition. But those improvements were measured in minutes, not hours, and new gray hairs. Plus, the Friday deadline always loomed, every pad done and handed in by morning.

Then they’d start on the next week, trying not to worry about the feedback they all dreaded. Belichick and top lieutenants always handed back their work with corrections, sometimes more than 100, everything from the wrong number to the incorrect position to a receiver split off by half an inch. Sometimes, the football editors scribbled instructions on index cards; others, they covered the pads in sticky notes. Some were as simple as three letters: W-T-F. Worst case, they were asked to start over, either with a particular sheet or for a full game, the “ask” rhetorical in nature. Some coaches—as in the case of Pepper Johnson—were deemed too slow and removed from the process. (Not that Peppers considered his demotion a bad thing.)

The pad laborers developed acceptable workarounds. Like laboring in groups in which each assistant handled his area of expertise for each diagram. Or using stats-and-information services. Or, in the case of current Giants defensive coordinator Patrick Graham, begging his wife to help him finish, incentivizing her with the promise of a date, if time allowed. Pamela Graham assisted with the production end, rather than the schemes. Sometimes, while cutting one play or another, she’d fall asleep, slicing through her husband’s precious handiwork.

In the playoffs, assistants padded even longer, because they needed to work ahead but didn’t know their exact opponent. They became amateur oddsmakers, paying more attention toward the teams they believed would win. Bad bets meant even more slogging, like the time Ferentz and another assistant completed their diagrams and retired to a bar, expecting the Patriots to face the Ravens, with one caveat—unless “it goes sideways.” It did. They headed straight back to the office for an overnight.

Padding is so deeply ingrained in Ferentz that sometimes, even now, when he’s struggling to find a schematic solution, he’ll head to the supply closet, grab his tools and begin to draw like it’s 2009. Usually, he unearths solutions through the process he once disdained. By now, he sees padding as two windows that speak to the same sentiment: one, into Belichick’s brain; the other, into how football is passed down. Neither window is revealed quickly, because it’s hard to spot genius while toiling at 3 a.m.

It becomes clearer over time, because of what they see (tells, tendencies, nuance, weaknesses buried deeper than typical charting would uncover), improvements in recognition speed and accuracy, and the payoff Belichick seems to seek. Once the padders become faster and smarter, they can, in theory, replicate how their opposition thinks. When they understand that, they can apply an opponent’s thought process to how that opponent would ideally approach them. And the clues that make that sequence as valuable as an overstuffed bank vault are most often found in one place: pads.

For example, if No. 96 is deployed in multiple positions one week, based on certain situations, or switching on only certain downs, they would wonder the obvious. Why? Turns out, No. 96 plays right defensive end, except for on third down, when he swaps in at right defensive tackle. Now they’re onto something. Maybe that defense viewed the opposing left guard as the weakest link and wanted to attack him, best player versus worst player, netting theoretically improved odds. Or perhaps No. 96 excelled at rushing up the middle, but only when allotted enough time, meaning he lined up at DT on obvious passing downs.

The pads, because of the painstaking detail that goes into them, provide better, more-informed guesses, or cold and exploitable truths. They also assist coaches in the next part of the sequence, an exercise in extending the logic they mined from the clues.

Same example. If Team X used that approach with No. 96 against Team Y, they would wonder, where are they—the Patriots—weakest, and how might Team X target them? At that point, they’re simultaneously starting to see NFL football through Belichick’s eyes and bolstering his game plans, two reasons that elevate padding above other types of busywork coaches pride themselves on inventing.

Only weeks into his tenure as a diagram grunt, Ferentz understood the basics of padding and how to draw. But the more he padded, the more every seemingly disparate part of football started to connect. Decisions made by offensive coordinators that changed a quarterback’s tendencies (throwing more quickly one week, speeding up the tempo) were made to cover up an injury to a lineman.

Or, say, the pads showed a clear pattern for an offense near the goal line. That offense was, say, the Seahawks, and they tended to, perhaps, attempt a particular slant route when within five yards of the end zone. Sound familiar? It should, because in Super Bowl XLIX, the clues from the pads led to extra reps for New England defensive backs in that very situation against that very route. And when only two yards separated the actual Seahawks from imminent victory, cornerback Malcolm Butler knew exactly where to be and precisely what to do, setting up his triumph-sealing interception.

When the assistants utilized that sequence, they realized why they had spent all those hours doing football art projects that wouldn’t fetch $1 on the street. They understood that winning—the metronomic, yet striking consistency that defines Patriots football under Belichick—is built on small details, and not just what can be gleaned, but how it might be useful, and how it is applied. They have effectively peeled the onion that is coaching to its core, while creating, essentially, FBI profiles on opponents.

The approach extended to how assistants coached as well. By considering opponents in overwhelming specificity, they could then whittle down their findings to the most important elements, which is all they passed on to players. Belichick might consider hundreds of factors in any one game, but he wants his Patriots to focus on no more than two or three specific to each player, funneling complexity into digestible emphasis. “Bill is better than anybody in the world at making complex things extremely simple,” Ferentz says.

The minutiae, while painstakingly obtained, adds up to a larger lesson, perhaps the most pivotal wisdom that Belichick imparts. That detail matters as much as anything in coaching, even when it comes to using the same pencils (because they broke less frequently and wrote more clearly) or white erasers (because they left fewer smudges).

And, of course, why he made his assistants pad, while all of them cursed under their breath.

The process of padding, like all processes relying on intense, improvable manual labor, evolved over time. Nobody interviewed would lay out what, in total, had changed in the approach, either because they didn’t know or because they feared Belichick’s ire for spilling even benign state secrets. More than 10 assistants who padded did not return interview requests. Others simply declined. One, when asked whether he could send a picture of one page of one pad he kept, asked, “Are you crazy?” then added, “I’d have to kill you.”

Still, some portions of what changed were disclosed, although mostly via whisper. An approach that started on both sides of the ball eventually became exclusive to the defense, starting in the mid-2000s. The Cookbook took on other names. Microsoft Excel spreadsheets provided templates that eliminated some of the sketching. Betamax machines and VHS tapes gave way to iPads. Cut-ups could be created in minutes, rather than hours.

Eventually, Belichick did away with the physical pads (we think). No one cops to exactly when, and some insist the Patriots must still use actual paper. (The team declined to make any current assistants, or Belichick, available for interviews, noting that they were busy preparing for a playoff game.) When Graham left in 2016, New England had yet to fully modernize its approach, still reliant on paper, scissors and tape—just ask Pam! Now, the Patriots incorporate visual images into their diagrams, bolster their takeaways with analytics and digitize their modern cookbook.

Over the same time period, offensive football evolved, too, and those shifts impacted the padders. Offensive coordinators increased the variance of their play calls, adding endless twists to plays designed to look the same—creating extra work for the artists laboring at 3 a.m. Schemes that once seemed complex are now antiquated. Ferentz cites Rex Ryan’s defenses with the Ravens and the Jets. Patriots staffers used to refer to his schemes, with players shifting all over the field to induce confusion, as Star Wars. “It would be tame now,” Ferentz says. “Like Atari.”

Regardless, the basic elements—details, knowledge, application, all to see the game with the same eyes—remain, entrenched, untouched by time gone by. “They’re looking for consistency, perfection and insight, still,” Scarnecchia says.

Which begs a question: Why don’t more teams pad, or at least emphasize the level of detail padding requires like the Patriots? For all the Belichick assistants who went on to other jobs, only Patricia is believed to have taken padding with him (to Detroit, where he was fired after three lackluster seasons, before returning to the Patriots). Ferentz sometimes considers teaching his staff at Iowa the process, but he worries everyone would quit.

The Patriots might be the only team still padding, in whatever form their approach now assumes. That is unsurprising, given the busywork involved in an era of efficiency. It’s also short-sighted, in that recovering padders cite numerous examples of padding’s impact beyond Butler’s interception. Remember that shocking offensive game plan in December, when Mac Jones attempted only three passes against the Bills? Those padders would bet their last dollar that the clues informing such drastic pivot came from, if not actual pads, then the ethos of padding.

Watch NFL games online all season long with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Or how about Super Bowl LIII? The Patriots, according to the recovering padders, flummoxed Sean McVay’s vaunted Rams offense by focusing almost exclusively on stopping one run play and all its variations. Because McVay, they believed, loved that play the most. Where else would New England’s coaches have uncovered the hints that netted another ring? The padders’ best guess: by charting and dissecting all the variations of it, in order to understand that the Rams’ rushing attack could be neutralized not by stopping all run plays, but by stopping one in particular around which the rest of the offense rotated.

The impact can be seen every Sunday, across the league. When Tom Brady, now in Tampa, motions for a receiver to shift two inches right or left, those who padded see him correcting a split that’s off, ever-so-slightly, but just enough to ruin his ability to separate. At least until Brady makes a tiny correction that can flip the outcome to a touchdown.

So while almost everything in pro football evolves, Belichick does in some ways but not in others. He’s still Mr. Details Matter, whether for drills, pads, pencils or anything. He’s perhaps the only active pro football coach who can still scout by hand, a padder, forever, in his soul. “If you don’t learn football in New England,” Pepper Johnson says, “then you was never interested in the first place.”

So many coaches did learn football in New England, and they learned it through padding. But when those coaches eventually left for bigger jobs, none could recreate what Belichick had created. He made them smarter, like Ivy League football graduates. But they weren’t him. They couldn’t carry the Patriot Way elsewhere, not with anything approaching the same neighborhood of success.

As Ferentz sees it, that’s padding’s biggest drawback, that the notion of what separates padding from other forms of football evaluation is Belichick himself. “I’ve just seen a lot of people leave that building too smart for their own good,” he says. “They think they’re smarter than everybody, and, in some ways, they are.” Just not as smart as Belichick.

Still, the lessons linger, all but burned into their brains. Even for a Hall of Fame player like Ozzie Newsome, those early days spent padding for Belichick in Cleveland revealed how much he didn’t know. Padding taught Newsome to differentiate, forming the backbone of his extended tenure in Baltimore as one of the most successful personnel executives in football. His pair of Super Bowl rings “started in what was basically a production lab,” he says, “a factory of football.”

While Belichick might present a curmudgeon-like front in public appearances, in padding and other crucial means of preparation, he encouraged new ideas, regardless of salary, or position. He wanted pushback but retained the final say. He sought understanding beyond right answers, because that understanding could be applied to everything else. That became part of the padding impact, too. Once the value became clear, assistants handed down their pads like family heirlooms to the next sleepless zombie ready to join their fraternity.

“It’s the honest-to-God truth,” Scarnecchia says. “In the three years I padded, it made me a better football coach. I thought I knew offensive football, and I had a pretty good understanding of it. But it gave me greater detail on the concept and what the defensive staffs are looking at. It was a revelation.”

Even then, he says, “There’s never an ace padder. Because, remember: That’s the job from hell, and you could never be right.”

Ferentz still splices his own game film, because if he doesn’t, he feels like he’ll miss something. And whenever he’s diagramming, he considers how Belichick might evaluate his work. He still sees 75 sticky notes that no longer exist. “His opinion is the one that matters to me,” Ferentz says, “and that’s the highest compliment I can give.”

Sure, Ferentz lived a nightmare, inducing what recovering padders might call PPSD (post-padding stress disorder). But the sickest part? Most days, Ferentz longs to pad again. So whenever he’s stuck, he can imagine himself sitting in a closet, with his white erasers, six-inch ruler and No. 2 Ticonderoga.

• Mac Jones: Reassessing the 2021 Draft’s Most Polarizing Player

• A Quarterback Evolution and a Coaching Revolution

• The German Import Helping Define the Post-Tom Brady Patriots

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.