One Man Knows What Tom Brady Is Going Through

Early one Sunday evening, fresh off 18 uneventful holes at a golf course near his Tampa home, Steve DeBerg switched on his phone in the clubhouse to find a flood of texts and voicemails from various friends, all of them reacting to the breaking news that was then blowing up the sports world. “They had mixed emotions,” DeBerg says. “They were excited, then disappointed.”

The excitement stemmed from the news itself, that Tom Brady was ending his short-lived retirement to return for a 23rd season. “A lot of my best friends live down here, so they’re big Tom Brady/Buccaneers fans,” DeBerg explains. The chagrin was due to the decision’s implication for their pal: With Brady turning 45 on Aug. 3, a month before Week 1, DeBerg will soon relinquish his longstanding title as the oldest quarterback to start an NFL game.

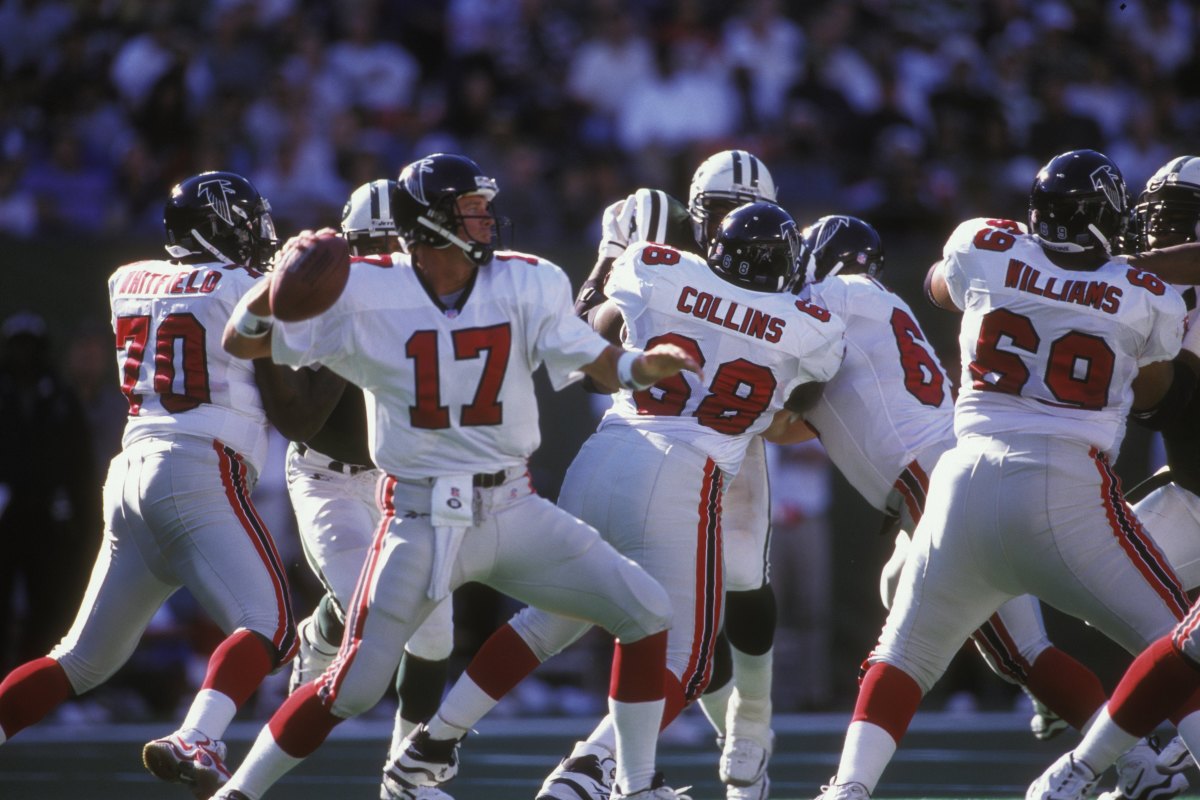

For his part, DeBerg—whose last start came with the Falcons in October 1998, at 44 years and 279 days—recalls feeling “happy that the record would continue” when he heard that No. 12 was hanging it up—even if he didn’t believe it at first. “I thought it was a joke,” DeBerg says. “[Brady] had just had a fantastic year. Probably should’ve been MVP.” Despite Brady reversing course 40 days later, though, DeBerg isn’t the least bit bummed.“If I’m gonna be second to anybody, Brady would be my pick,” he says. “I think he just had unfinished business and wants to give it another shot.”

Now 68, DeBerg can relate better than anyone to the urge. A 10th-rounder for the Cowboys in 1978 who famously wore a shoulder-mounted speakerbox and helmet-clipped microphone during an ’80 game to overcome a bout of laryngitis, he threw for more than 34,000 yards across 17 seasons for six different teams, duping defenses with his deft play-action skills. “One of the best ballhandlers ever,” says Bruce Arians, who coached the running backs in Kansas City when DeBerg was there from ’89 to ’92. “I used his tape to teach Peyton Manning how to fake.” Yet Steve DeBackup, as the L.A. Times once described him, was perhaps best known for two things: the star-studded list of Hall of Fame signal-callers with whom he once shared a depth chart—Roger Staubach (Cowboys), Joe Montana (49ers), John Elway (Broncos) and Steve Young (Buccaneers)—and the audacious comeback he pursued in ’98, nearly five years after his last NFL pass.

In his time away DeBerg had stayed close to the game, spending two seasons under Dan Reeves as a Giants assistant and later joining a coed touch football league in Tampa, where every so often he also would meet up with former teammate Vinny Testaverde to toss the pigskin around. But it wasn’t until his son Drew was entering high school and expressed a desire to go out for quarterback that DeBerg began reconsidering retirement. “I started showing him drills, and I was surprised that my arm strength was basically the same,” DeBerg says.

Emboldened, DeBerg typed up notes on letterhead to five teams that he thought might consider his services. “Just for the heck of it, to see if I could,” he says. “It was totally a long shot.” One of the notes was addressed to Reeves, then with the Falcons; somehow, though, it wormed free of the envelope in transit and reappeared in DeBerg’s mailbox two days later. “I was trying to decide if should I call Dan or resend the letter, and my phone rang, and it was Dan wondering why I sent an empty envelope,” says DeBerg. He’s never forgotten the conversation that followed:

DeBerg: I wanted to see if you’d be interested in me coming out of retirement.

Reeves: Steve, I thought you were smarter than to get back into coaching.

DeBerg: No, I’m thinking about coming back as a player.

[Long silence for what Deberg says “seemed like 10 minutes.”]

Reeves: Are you out of your mind?

After getting his old boss to realize he was serious, DeBerg drove from Tampa to Atlanta and impressed enough at a June 1998 workout to earn a recommendation from Reeves that the team sign him. It seemed like an ideal match, given DeBerg’s familiarity with Reeves's system, having also played under him in Dallas and Denver. The Falcons also had a sudden need for a proven backup, with Mark Rypien having stepped away to take care of his cancer-stricken wife. Nonetheless DeBerg had some convincing to do.

“I was negotiating my contract with [GM] Harold Richardson, and he didn’t think I was going to last a week,” DeBerg says. “He thought it was a joke that I was even in his office.”

From the moment his veteran-minimum deal was announced, plenty of others weren’t shy about treating DeBerg’s age as a laughing matter, too. Teammates reportedly called him Grandpa, or David Hasselhoff. Sports Illustrated ran a chart comparing DeBerg with Otzi the Iceman, an ancient corpse whose remains were on display at an Italian museum. (Examples: “preserved by: ice packs/glacier” and “Older than: Bill Cowher/Moses.”) A wire service quoted his life insurance agent confirming that his policy remained active. “Shouldn't Steve DeBerg be scheduling a golf game?” the Tampa Tribune wrote. “Why isn’t he at his Tampa home looking over his investment portfolio instead of standing in the hot sun at the Atlanta Falcons’ preseason camp looking over a defense?” (To his credit, DeBerg rolled with the punches, telling reporters, “This is not a normal thing for someone to do. But I’m not normal, so I don’t really care.”)

A punishing preseason opener against the Titans threatened to prove Richardson’s one-week prediction correct. “I was definitely sore all over,” DeBerg says. “Just like a 44-year-old would be.” But he worked hard to patch his flaws; a team PR official at the time reported seeing DeBerg practicing the footwork for his dropbacks on the practice field one night at 10:45. And it paid off with an encouraging final tuneup before the regular season, a 17–0 win over the Bengals, after which Cincinnati defensive back Corey Sawyer lamented to reporters, “You know, I just can’t believe a 44-year-old guy can throw the ball everywhere on us. … You just don’t go letting a guy like that push you around.”

DeBerg officially debuted in garbage time against the Panthers in Week 4, becoming the league’s second-oldest signal-caller ever, behind George Blanda. (“DeBerg, I think, once babysat for Blanda,” a Miami Herald columnist quipped.) But his record-setting—and only—start came in Week 7 against the Jets, a contest the Philadelphia Inquirer billed as “undoubtedly endorsed by the AARP.” Replacing the injured Chris Chandler for his first appearance atop the depth chart in 1,777 days, DeBerg was sacked three times and knocked down a dozen more by defensive coordinator Bill Belichick’s blitz-heavy scheme. He also lost a fumble that turned into a touchdown and threw an interception before getting benched in a lopsided loss.

“I only got to play the first half,” DeBerg says. “It wasn’t some big, heroic thing.”

Perhaps, but DeBerg also earned his share of admirers along the way. At the top of the list is Chandler, who led the Falcons to a 13–3 record and NFC title with DeBerg in his ear. “Steve was one of my mentors,” Chandler says. “He was the best teammate, friend, sounding board. He just gave me confidence. Every single practice he’d tell me, ‘You’re the best. You’re better than anyone out there.’ It was a really positive relationship.” But even opponents were impressed with what DeBerg was pulling off. “He’s unbelievable,” Elway told reporters before Denver met Atlanta in Super Bowl XXXIII. “He’s got nine lives.”

Looking back, DeBerg takes the most pride in the Falcons’ team success throughout that ’98 season. While he didn’t make it off the sidelines as the Broncos won in a rout, he still made history as the oldest player on a Super Bowl roster; today his NFC championship ring and Super Bowl jersey are prominently displayed in his trophy case. “It was just an amazing year, to be able to experience that,” he says.

It was so enjoyable that DeBerg actually entertained coming back again at 45 … at least until he blew out his right knee in a motorcycle accident and called it quits. Two decades of privately training quarterbacks came next, but he gave that up a few years ago to retire for real. These days, in addition to hitting the links, he fills his time with yard work, bike rides, pickleball matches and vacations to visit his two grandkids in Raleigh. He hasn’t fully shaken football, doing the 18-minute drive from his place to Raymond James Stadium for about half of the Bucs’ home games each season.

DeBerg is quick to point out that any comparison between him and their current quarterback starts and stops at their age. “Our careers are completely different,” he says. “I saw one of his rookie cards sold for $3 million. And you could probably buy mine for $15 or $20.” Then again, maybe he shouldn’t be so dismissive of his own legacy. As Arians, now Tampa’s coach, puts it with a laugh, “Steve was extremely bright [and], just like Tom, extremely competitive.”

DeBerg has never met Brady since the latter arrived in March 2020. “I’m hoping I’ll be able to get that opportunity this year,” DeBerg says. “I would just congratulate him on a fantastic career. All the accomplishments he’s had, there’s nobody else that’s even come close.” Maybe one day the two could even hit one of Tampa’s golf courses, or perhaps a pickleball court, and have a deeper conversation about their experiences as super-old signal-callers. At the very least DeBerg would love to shake Brady’s hand and offer his congratulations for breaking his record.

“I had it for a good while,” DeBerg says. “He'll probably have it even longer.”

More NFL Coverage:

• Good Thing the Bucs Left the Light on for Tom Brady

• How 22 Women and Deshaun Watson Got Here

• The Tyreek Hill Trade and the New Normal in Roster Building