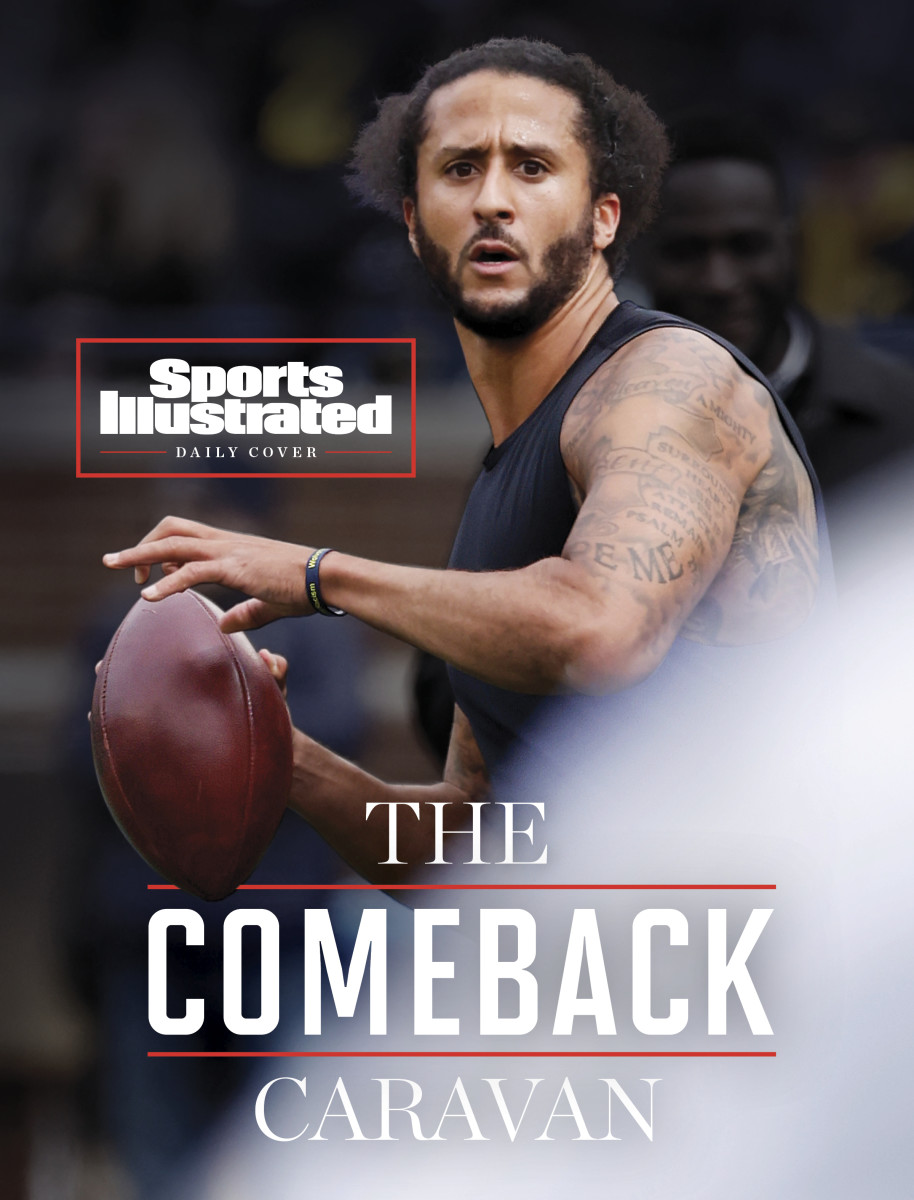

Behind the Spectacle of Colin Kaepernick’s Comeback Tour

Xavier Rush was leaving the TSA checkpoint inside New Orleans International Airport one Thursday last month, headed to a weekend bachelor party, when he checked his phone to find four new missed calls, from four different friends in the area. All were inquiring about the same thing: “Everyone was like, ‘Are you back by Monday? Kap’s gonna be here. Can you run routes?’”

No further details were offered in the moment—no time, no location, nothing beyond the simple fact that Colin Kaepernick was coming to New Orleans and looking to throw. Nonetheless Rush, a personal trainer and former Tulane receiver, committed on the spot, and less than 72 hours later he reported to a high school stadium on the west bank of the Mississippi River alongside a small group of fellow area pass-catchers who had been enticed by similar appeals.

“I was coming back Sunday already, but I put my schedule together to make sure I’d be available,” Rush, 29, says. “I was excited to help him continue to showcase his talents. I was also curious. Like, ‘O.K., does he still have it? Is he good as he thinks he is?’”

So it went as the ex-49ers quarterback hit the road to address those very questions, touching down in eight cities across three time zones over 10 days from March 14 to 24, often with little notice for locals as plans audibled on the fly. But no matter the site—in order: Scottsdale, Houston, Dallas, Atlanta, New Orleans, Seattle and Los Angeles—the 34-year-old was always met by sympathetic hosts eager to signal-boost his message to NFL front offices. “Yessir!!” Seahawks wideout Tyler Lockett tweeted afterwards in Scottsdale. “That man Kap is ready!!”

It wasn’t the first such public campaign from Kaepernick (who did not respond to an interview request for this story); in late 2019, the same year he and ex-teammate Eric Reid settled a lawsuit alleging that league owners had blackballed them for kneeling during the national anthem in protest of police brutality and racial injustice, disagreements over media access and waiver language reportedly led him to bail on an NFL-run tryout in Atlanta and host an alternate event instead. But only eight scouts attended, and zero contract offers came.

Whether this current push will end differently remains uncertain. Five years removed from his last real snap, in a 25–23 loss to Seattle on New Year’s Day 2017, Kaepernick has made it clear in sporadic interviews that he doesn’t need a guaranteed roster spot; he merely wants a chance to “walk through the door” of an NFL facility for a workout. But given that he has spoken directly to just one team—the Seahawks, in 2017—since leaving the league, it’s fair to wonder how many front office decision-makers actually possess the moral courage to stomach the inevitable media circus and bad-faith criticism that would accompany such an invitation, let alone a possible signing.

Regardless of where it ends up, though, there is undeniable buzz around the Colin Kaepernick Comeback Tour, which chugged on this month to a halftime showcase during Michigan’s spring game—reuniting Kaepernick with his former coach Jim Harbaugh—and later southeast Florida where social media videos showed him passing to the likes of Jarvis Landry and Brandon Marshall. Part of this no doubt reflects Kaepernick’s personal efforts to drum up attention as he strives to address what he has described as “unfinished business” in football. “It’s his competitive mindset,” veteran quarterback Tyrod Taylor says. “Like, ‘If there’s any doubt I can hold my own, come to these throwing sessions.’” But it is perhaps more indicative of the increasing number of current and former players, coaches, trainers and others rallying to Kaepernick’s side throughout his travels, close to 20 of whom spoke to Sports Illustrated about their experiences crossing paths with the quarterback, watching him throw for a few hours, chatting him up for a few minutes and learning a little about what it is like to walk a few yards in his cleats.

“It’s definitely going to be a great story [to tell] down the road,” Cardinals receiver Antoine Wesley says. “Got to meet a legend, know what I mean?”

On March 13, less than a week before Rush’s phone blew up, Kaepernick took to Twitter and posted a clarion call for his 2.4 million followers. “For [t]he past 5 years I’ve been working out and staying ready in case an opportunity to play presented itself,” he wrote. “I’m really grateful to my trainer, who I’ve been throwing to all this time. But man, do I miss throwing to professional route runners. Who’s working?? I will pull up.”

Just 10 minutes passed before Lockett replied, offering up the services of himself and his brother Sterling, a Kansas State commit and fellow wideout. Kaepernick responded that he was heading to Scottsdale, and indeed the following afternoon they all pulled up to Saguaro High School, where Kaepernick’s camp had booked the stadium through a mutual connection with Nike, which sponsors both him and the school’s football program. One day later, he popped up at Houston’s Strake Jesuit High, slinging to a group that included the Bills’ Marquez Stevenson and the Eagles’ Greg Ward, and the next evening saw him doing the same to Wesley, Philadelphia’s Jalen Reagor and others at First Baptist Academy in Dallas.

A spontaneous spirit would continue to drive Kaepernick forward, though parts were more calculated than they seemed. For instance, Dallas-area trainer David Robinson first learned about Kaepernick's interest in swinging by about a month in advance—not long after he and his wife Amber had finished watching Colin in Black & White, an Ava DuVernay–produced Netflix series based on Kaepernick’s experiences as an adopted Black teenager of white parents in California’s Central Valley. “I got a text from his agent [Jeff Nalley] saying ‘Kaepernick wants to throw to some of your receivers,’” Robinson says. “I told my wife, ‘Man, this is crazy.’”

Robinson recalls the exact date of the workout arriving a week in advance, over a group chat with Nalley and Kaepernick; the trainer arranged for it to be held at First Baptist, where he also works as offensive coordinator. Then, the night before, he got a surprise call. “[Kaepernick] said he was about to tweet that he was coming to Dallas, so he wanted me to reply and say, ‘We’re here, come pull up,’” Robinson says. "I was like, ‘I see you strategizing, Kap; I like it!’”

Other stops required more resourcefulness: In New Orleans, a morning session at Tulane was scuttled when Kaepernick’s camp was informed of a scheduling conflict at 7:30 a.m., leading to a hasty relocation to Edna Karr High School, the alma mater of a visual artist and Kapernick friend named Brandon Odum, who was helping coordinate the visit. A comparable situation unfolded before the Los Angeles workout, with a morning-of switch from a Pasadena high school, though only because Team Kaepernick locked down UCLA at the last minute. “I was thinking, ‘Wow, how’d you pull that off?’” trainer Darran Matthews says.

Less difficult was finding enough willing receivers to show up; after Kaepernick tagged Robinson in a tweet about coming to Dallas, the trainer recalls having to turn away “a lot of guys I’ve been working with for a while" who suddenly slid into his texts, emails and DMs in search of a spot. “I had people who wanted to pay just to come watch,” Robinson says.

Like Rush, some were driven by curiosity: How would Kaepernick, who still holds NFL records for rushing yards by a quarterback in a single game (181) and an entire postseason (264), look, move and throw? Others came for simpler reasons. “He was just looking to get some work, I’m looking to run some routes,” Saints receiver Jalen McCleskey says.

Plenty, like Travis O’Connor, wanted to be there at least in part because of what the quarterback means to them. A draft-eligible wideout from Southern University, the New Orleans native can still picture his younger self in front of the family television, rooting for Kaepernick and the Niners as they fell short against the Ravens in Super Bowl XLVII. And when Kaepernick never found an NFL job again after kneeling, it led O’Connor to examine his own future in the sport. “It was very discouraging, especially as a Black man,” he says. “It made me question if I really wanted to be a part of something that wouldn’t even support me.” So when O’Connor saw a March 20 tweet from his usual workout partner McCleskey asking Kaepernick to pull up to the Big Easy, he made sure to tag along.

Avery noticed this theme in Atlanta, where Kaepernick joined fellow Black signal-callers Taylor, Justin Fields and Joshua Dobbs for a two-hour session at Morehouse College, an HBCU and Avery’s alma mater. Sure, the group probably would’ve been out there anyway if Kaepernick hadn’t come, drilling dropbacks and rollouts and goal-line scenarios all the same. But Kaepernick’s presence imbued the workout with larger implications.

“I’m a big fan of all the things he’s done, so any chance I get to be supportive of him, to go with other top guys, it’s important that I do that,” Avery says. “And I think that there’s a lot of Black people out there who would go out of their way to help Colin Kaepernick, because they know how much he sacrificed to make a message that many of us feel needed to be said.

“It’s not a lack of talent that’s preventing him from playing in the NFL. It’s going to take a rich white guy to decide that they too think what he did was important.”

For Taylor, now backing up Daniel Jones with the Giants, seeing Kaepernick at Morehouse was a “full-circle moment.” Eleven years ago, in the same city, the pair shared a training gym in the leadup to the 2011 NFL draft combine. And now here they were again, hugging and laughing and marveling at how time had flown by. “I was joking with him about how he had some gray hairs,” Taylor recalls. “I said, ‘Man, what’s going on?’ He’s like, ‘Life changes you in five years!’”

Kaepernick, who will turn 35 around the midway point of the 2022 regular season, knows the clock is ticking, those present at his workouts recall. “I can’t say it's the last go, but it’d be tough if he doesn’t get in after all this,” Robinson says. And so, on top of everything else in his life—the Netflix series; a publishing company that recently released both his semi-autobiographical kid’s book, I Color Myself Different, and a Kaepernick-edited anthology of essays on police abolition; and an educational campaign, the Know Your Rights Camp, that among other programming offers free second autopsies in “police-related” deaths—he continues to crisscross the country in search of that one open door.

Accompanying Kaepernick on the road has been his personal trainer, Josh Hidalgo, a handful of associates coordinating logistics, and what struck some as a Hollywood studio’s worth of camera people capturing his every move. “There was a whole video setup, like Paramount,” says former receiver Marcus Peterson, recounting when he showed up to Kaepernick’s L.A. throwing session some 10 miles west of Paramount Pictures. “I’m being sarcastic, obviously, but he had a photographer on him, another guy going live, like three on the right side, one in the end zone, one in the sky box—just like UCLA filming its practices.”

But it wasn’t like other players were treated like extras on a one-man movie set, either. “Walking out, he personally introduced himself to everybody,” says Corey Russ, a tight ends and running backs coach at Morehouse who helped arrange the Atlanta workout. “He’s a polarizing figure, but that’s not the vibe he gives off. He’s somebody who really cares about what's going on around him. That was the most impressive thing to me: There was a humbleness about him.”

The sessions themselves all followed near-identical formats. First the receivers warmed up while Kaepernick did the same with Hidalgo. Next they came together to help Kaepernick loosen his arm, and then worked through the whole route tree—comebacks, curls, digs and so forth—at varying down-and-distance scenarios before finishing more than an hour later with goal-line work. “I felt like I played a full game,” O’Connor says. “We didn't even take breaks. We got water in between reps, but we were just going-going.”

As the day wore on, Oklahoma Baptist wideout Keilahn Harris found Kaepernick sidling up next to him to offer tips on how to read certain coverages and what depths to run certain routes. “He was coaching me up,” Harris says. This was another experience of many attendees, from O’Connor in New Orleans (“He was dropping knowledge on us”) to fellow quarterbacks like incoming UCLA freshman Justyn Martin in Los Angeles. “Then he’d play defense, mirroring the receivers to show them how it’d be in the game,” Peterson says. “He was like a coach, a quarterback, a receiver, a DB all in one.”

Exact locations for the workouts were never publicized in advance, so attendance was always sparse (aside from the participants, Kaepernick’s team, and select guests ranging from local media to New Orleans city councilman Freddie King III). But that didn’t stop word from spreading once Kaepernick showed. “All it takes is one person to create the buzz,” Russ says, explaining the flock of Morehouse players that gradually filtered onto the sidelines as the workout wore on.

Kaepernick was more anonymous at a Bruins’ practice facility regularly populated throughout the offseason with NFL players passing through Los Angeles, including Panthers running back Christian McCaffrey earlier that same morning. But his appearance still attracted at least one well-known guest in UCLA coach Chip Kelly, whose lone season helming the Niners, in 2016, coincided with Kaepernick’s last in the league.

Wandering out from his office, Kelly chatted up Kaepernick for about half an hour while the latter stretched. They covered where Kaepernick was based these days (New York City); how his body looked and felt (Kaepernick told Kelly that he was up to 230 pounds, five more than his listed playing weight); and his hopes for the tour. “He believes he has something left,” Kelly says. “He just wants an opportunity to get in front of some team and let them see where he is.”

Asked what the likelihood is that Kaepernick will actually receive such a chance, though, Kelly says, “I don’t know that. I haven’t talked to anybody [with an NFL team about him]. I thought he looked great physically. I really enjoyed my time coaching him. I think he’s a really, really good player. I think he deserves a shot. But I don’t have any influence on that.”

Peterson knows what it’s like to travel the world in search of a shot. Born and raised in Los Angeles, undrafted out of D-2 Seton Hill, he has attended minicamps with the Browns, Jaguars and Chargers; earned his MBA while playing in London; and tacked on stints with the Indoor Football League and The Spring League for good measure. So when Kaepernick was done throwing at UCLA, Matthews approached him and handed over a T-shirt from his apparel line. “It says, STAY PERSISTENT,” Peterson says.

Another sight at every session: Kaepernick sticking around long after his final throw to pose for pictures, answer questions and otherwise spend time with those who lent him theirs. Wesley thanked Kaepernick “for what he’s done” in his activism, and then picked his brain about busting cover-2 defenses. O’Connor absorbed a lesson about the importance of developing timing with the quarterback; Matthews felt a bond form over their mutual membership in Kappa Alpha Psi, a historically Black fraternity. “He asked how my pops was doing, so I called him and they talked on FaceTime for a while,” Taylor says.

Certain relationships endured even once Kaepernick departed, some in part for professional reasons—Avery says Kaepernick asked for help connecting with NFL decision-makers, so the trainer forwarded his information and workout videos to “a few different teams”—and others purely personal: McCleskey says that after two tornadoes later ripped through his native New Orleans, Kaepernick hit him up to check whether the wideout’s family was safe. (They were.)

Along these lines, whether or not an NFL tryout awaits Kaepernick, those who have trained with him predict that this tour will not be in vain. After five years of staying ready through mostly solo workouts, throwing to no one but Hidalgo, he is experiencing the rush of being in a team setting again. “That’s exactly what it was—reconnecting, being back in that football family,” Wesley says.

Matthew Hatchette came to the same conclusion as he was organizing Kaepernick’s L.A. stop, having been tabbed by an old Nike acquaintance on 24 hours’ notice. “As athletes, we get out among our peers, we just enjoy that time,” says Hatchette, a former Vikings, Jets and Jaguars receiver who regularly arranges workouts for active players such as Amon-Ra St. Brown. “If he ends up going to the NFL, great. But I think he loves the sport so much that this is fun, relaxing, stress-free. I have a feeling that’s what he’s getting out of it: a psychology session, if you will.”

Or maybe it is really as simple as Kaepernick feeling as though he has unfinished business in football. That’s what receivers coach Hilton Alexander thought watching Kaepernick stick around on the Morehouse field for at least an hour after that morning’s session. “He’s continued to stay in shape, doing a lot of things to bring awareness to his situation,” Alexander says.“This is just the next step, getting the approval of your peers.”

Peer approval can only get Kaepernick so far, of course. But he is staying persistent. In Atlanta, when Alexander worked his way to the front of the line of picture-seekers, he asked how long the quarterback was staying in town. As Alexander recalls, “He said, ‘Eh, I don’t know, just trying to find the next spot.’”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Sportswashing Is Everywhere, but It’s Not New

• Rory McIlroy Was Once the Next Tiger Woods. So, What Is He Now?

• We Haven’t Seen the Best of Shohei Ohtani