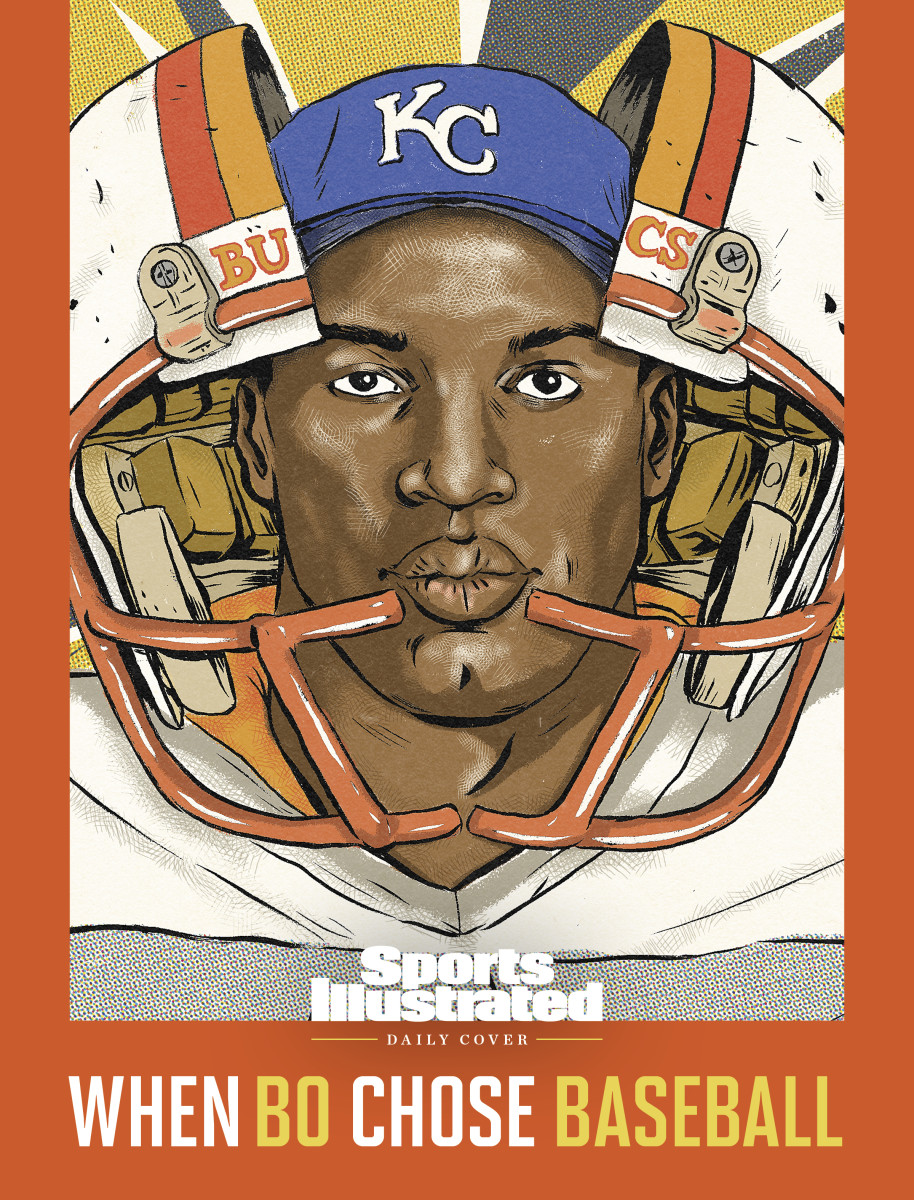

With Bo Jackson the Bucs Were Once Handed a Unicorn Running Back. Here’s How They Blew It.

Excerpted from the book THE LAST FOLK HERO: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson, by Jeff Pearlman. Copyright © 2022 by Jeff Pearlman. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Sometimes people ask questions even though they know the answers.

For example ...

Who would win in a fight, King Kong or The Hulk? (The Hulk, obviously.)

What’s the best Hostess snack? (Duh, Ding Dongs.)

Who’s the coolest member of Menudo? (Xavier.)

And in the early months of 1986: Will Auburn’s Bo Jackson play professional football or major league baseball?

So obvious was the answer that to engage in debate was illogical. Sure, Bo Jackson was an excellent collegiate ballplayer with all sorts of talents. But clearly his future was in the NFL. It had to be. He was the reigning Heisman Trophy winner and the best running back prospect to emerge from the collegiate ranks since Orenthal James Simpson departed Southern Cal in 1969. Even though the stingy Tampa Bay Buccaneers held the first pick in the upcoming draft, there was no way the franchise would let a phenomenon like Jackson slip through its fingers.

Plus, there were the financial logistics: Should Bo Jackson choose baseball, he’d be languishing in the minor leagues for—at bare minimum—a year and a half. His signing bonus (based upon the average for first-round picks) would be in the $100,000 range. The NFL, by contrast, was a land of riches. The average first-rounder was gifted with $900,000 as soon as ink touched paper.

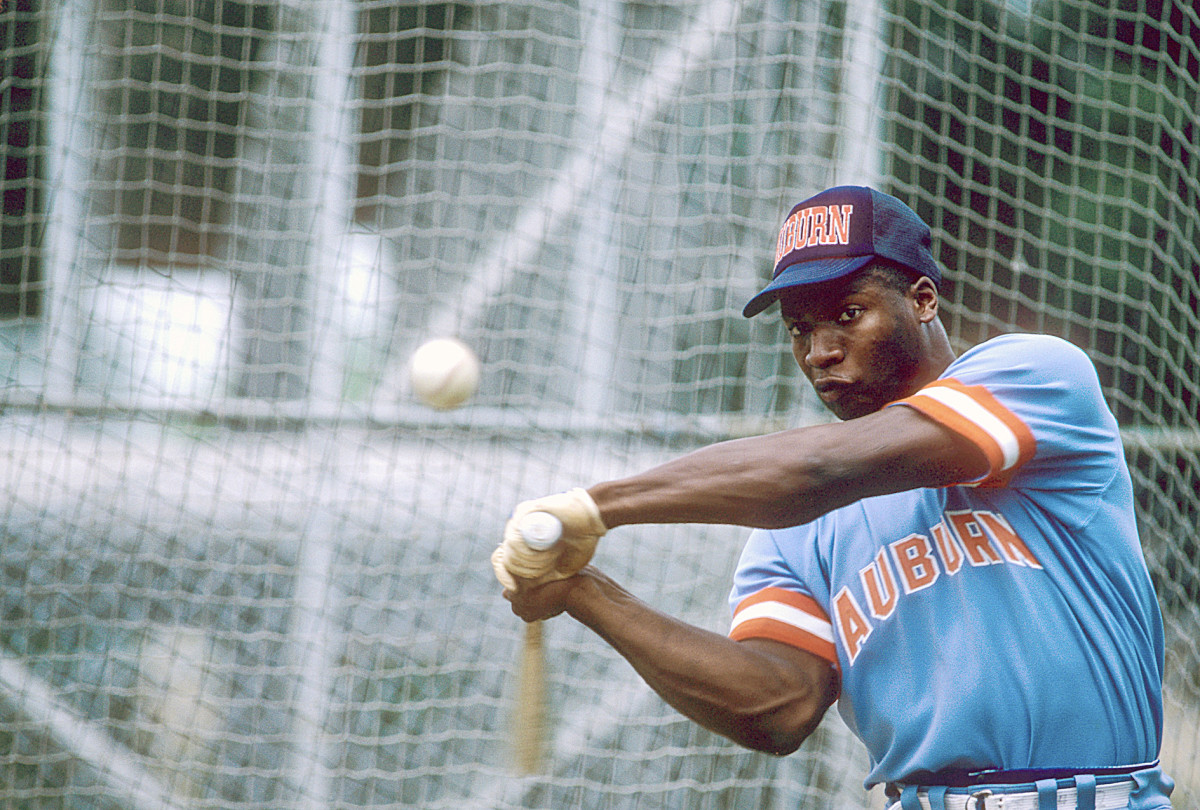

So as his time as a college football player faded and his life playing one final season on the Auburn diamond returned to focus, Jackson’s dodging of the weekly “Football or baseball?” inquiries (“I’m not telling until the summer,” he said at the time) felt almost amusing.

“He’s going to the NFL,” said Larry Himes, the California Angels’ scouting director. “I don’t think he’s going to be able to resist the hoopla and the dollars that go with the NFL draft.”

He had to be picking football.

In March, The Tampa Tribune published a profile that delved into the baseball versus football debate, including this revelatory nugget: “Jackson has retained Freland [sic] Abbott of Bessemer, Ala., as his ‘business manager.’”

Frelon Abbott had first met Bo when the kid was a local on-the-rise high school phenomenon. Abbott paid Jackson to mow his lawn, and he occasionally slipped the teen some dollars. A few years later, Abbott—an unofficial Auburn football booster—made it a priority to help the Tigers land McAdory High’s star. Which, of course, they did. Once at Auburn, Jackson was presented with regular doses of money and material possessions via Abbott.

Now Abbott was his “business manager.”

This information failed to raise eyebrows. Intended or not, Jackson didn’t use the term “agent” to describe his relationship with Abbott. He said “business manager.” An active SEC player could not have an agent. But a business manager? It was murky.

In the midst of the college baseball season, Jackson had little to no time to devote toward the upcoming NFL draft, which was scheduled for April 29. So he had Abbott handle any dealings with the Buccaneers. This was, again, very murky territory. Had Jackson been done with college sports, he could have used Abbott with no complication. He even could have signed a contract with the man. But as Auburn’s center fielder, the only person allowed to chat with the Buccaneers on Bo Jackson’s behalf was Bo Jackson. Nobody else.

That’s not what happened.

Who made the first call? All these years later, it’s impossible to say. But somehow, Abbott and Phil Krueger, the Buccaneers’ assistant to the president, agreed that on the morning of Tuesday, March 25, the organization would send owner Hugh Culverhouse’s private plane to Auburn Municipal Airport, pick up Jackson and fly him to Florida for a medical exam, then return him for that night’s baseball game against Alabama-Birmingham at Plainsman Park. “We didn’t have access to the players that [morning],” says Hal Baird, Auburn’s coach at the time. “So we were a little in the dark as to what they were doing with their time.”

As planned, Jackson boarded the jet, traveled the hour and a half to Tampa, landed and was ferried to the Buccaneers’ facility for a physical. Culverhouse’s plane brought Jackson back to Auburn later that afternoon and touched down just as the Tigers were taking pregame batting practice. “It was unusual for Bo to miss BP,” says Baird. “I don’t think he ever did.”

Baird asked aloud: “Does anyone know where Bo is?”

“Oh,” one of the Tigers said, “he’s not back yet.”

“Back from where?” asked Baird.

“He went to Tampa for a physical,” the player said.

“What?” Baird replied.

“Yeah,” the player said. “They sent a plane up, and he’s in Tampa taking a physical or something.”

S---.

“I knew,” Baird says, “that was bad news. Really bad news.”

Buy The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson

The coach was well versed in the intricacies of college eligibility. The NCAA, as a whole, permitted athletes to be professional in one sport, amateur in another. The SEC, however, was steadfast in demanding 100% amateurism of its participants. A flight paid for by the owner of a for-profit team would make Jackson a pro. “We have had the rule for as long as I can remember,” Boyd McWhorter, the SEC commissioner, said at the time. “People have to make that choice.”

As soon as Jackson entered Plainsman Park to prepare for the night’s game, Baird headed straight toward him.

“Bo,” he said, “tell me what you’ve been doing.”

Jackson informed his coach about the plane, then added, “It’s fine. We had it checked out.”

“Who had it checked out?” Baird asked.

“My business manager,” Jackson replied. “Frelon.”

S---.

“Bo,” Baird asked, “did you pay for the flight?”

Jackson shook his head.

“I don’t see how this was O.K.,” Baird said. “Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t believe there’s any circumstance where you can take a free trip or do anything for a professional team.”

Baird held Jackson out of that night’s 11–5 win. When the game ended, Baird called Pat Dye, Auburn’s football coach and athletic director. “Coach, we’ve got a problem here,” he said. “Bo made a trip to Tampa on the Buccaneers’ plane. I’m pretty sure he just ended his eligibility.”

Dye drove to Baird’s office. It was 11 p.m. Both men felt as if they’d been punched in the gut. Dye picked up the desk phone and dialed McWhorter’s home number. First and foremost an academic, McWhorter had earned a master’s degree in English from Georgia, then a doctorate at Texas. He was a by-the-book man who believed rules needed to be followed.

Although Baird wasn’t on the call, he sat across from Dye. Initially, the conversation pertained specifically to Jackson and the facts of the airplane trip. This is what happened. This is when it happened. This is who was involved. “But then I could tell in very quick order what was happening, because Coach Dye went nuts,” says Baird. “He undressed [McWhorter] like he was a yard dog. He was dog-cussin’ him, calling him every name in the book. He was citing all the things Bo Jackson had done for the conference.”

Toward the end of the call, Dye said to McWhorter, “Well, let him pay the money back and restore his eligibility.”

“That,” the SEC commissioner replied, “won’t be possible. He broke the rules. He’s ineligible to play any more sports for Auburn.”

Click.

The next morning, Baird summoned Jackson. He explained the violation and that any further involvement on the baseball team was impossible. Jackson was fairly stoic throughout the conversation. He apologized and fought back tears. “Then,” Jackson later said, “I went behind the dugout and cried.”

Over the next few days, a popular party game, Who F---ed Bo?, was a campus-wide rage. A good chunk of blame was applied toward the SEC—and with sound reason. “While all this was happening, the NCAA basketball tournament was going on,” says Baird. “The SEC office was empty, because reps were all over the country with basketball teams. So who knows who was managing the office and what was said to Bo’s guy when he asked if it was O.K. to take a physical. There was so much confusion, and it cost a young man who didn’t deliberately do anything wrong.”

The primary suspect, though, was the Buccaneers and, specifically, Culverhouse. It was his plane that ferried Jackson to Tampa, back to Auburn and then out of college baseball. When reached by the Associated Press, Krueger, the team assistant, insisted that he’d spoken with an SEC official before the flight. “I asked for clarification as to what could take place during Bo’s visit,” he said. “I was told no negotiations, no talk of money or contracts, no signing of a contract, and no representation of Bo by an agent. We abided by those restrictions.”

In the New York Post, columnist Dick Young slammed the Buccaneers, insisting the flight was a “put-up job” and that the team had to have been aware it would strip Jackson of his remaining eligibility. Wrote Young: “Now that there are to be no more at bats for the edification of big league scouts, it is felt that his baseball interest will wane. Pro football will have an open field.”

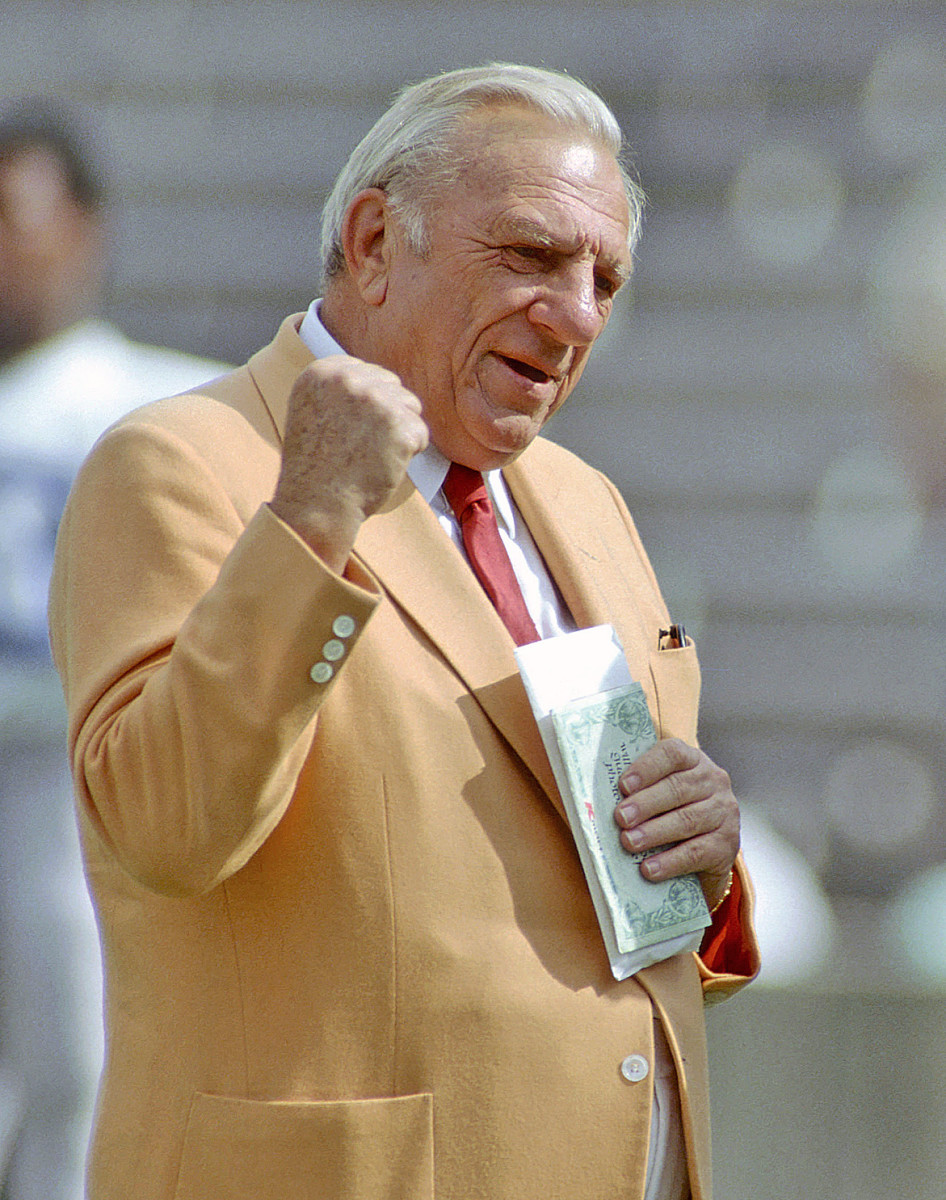

But this made little sense. The Buccaneers had the No. 1 selection. They wanted Bo Jackson, and 34 more college baseball games wouldn’t have changed that. So why intentionally infuriate him? Why take lengths to cause Bo Jackson harm? “My dad said stupid stuff a lot, but he wasn’t a vicious man,” Gay Culverhouse, Hugh’s daughter, said years later. “I don’t know the precise truth, but I’m pretty sure my dad wasn’t smart enough to purposefully destroy Bo’s ability to play baseball. I think it happened inadvertently.” (Hugh Culverhouse died in 1994; Gay died in 2020.)

Jackson was incensed, heartbroken and more than a bit humiliated. But while he held a grudge against the Buccaneers, his ire was mainly directed toward Abbott, his sorta-kinda agent. In an April 5, 1985, Atlanta Constitution piece, writer Chris Mortensen tracked down Abbott and told him the rumor was that he now served as Jackson’s agent.

“That’s not true,” Abbott said. “But call me next week.”

There would be no next week. Four years after the flight to Tampa, Jackson expressed his feelings concerning Abbott to Dick Schaap, his biographer. He did not hold back.

JACKSON: Up until this point, I can truly say there’s only one person that I literally hate, and that’s [Abbott]. The way he tried to make a fool out of me. I don’t even have to be in a pissed-off mood, if I’m driving down the road, I visualize this guy standing in the road, and I just wipe him out.

SCHAAP: He betrayed your trust?

JACKSON: If I had a chance to get in a ring with one person just to fight, I would kick his ass. We don’t have to be in the ring. We could be out in the yard for five minutes. Just let me kick his ass. … He’s a little weasel-type guy.

SCHAAP: What happened?

JACKSON: I think what he did with [Hugh] Culverhouse was: Culverhouse said, “Well, I’ll give you this if you get him to come down, get him ineligible so we’ll know that we have him.” … And I kicked his ass out.

With his collegiate sporting career officially over, and with Frelon Abbott persona non grata, Bo Jackson had a couple of big events circled on his calendar.

First, on April 29, 1986: the NFL draft.

Second, on June 2, 1986: the Major League Baseball draft.

The problem: He needed guidance.

So when the ugly aftertaste of the Frelon Abbott experience faded, he went about finding someone to trust. This ultimately led him to the office of Susann McKee, an Auburn-based Century 21 real estate agent whose daughter, Georganna, attended school with Bo. McKee was 41 at the time and had no experience in sports management. Bo, however, knocked on her door one day, introduced himself and said, “I don’t trust anyone.”

“Oh,” replied McKee.

“But I know your daughter and I know about you,” Jackson said. “I’m about to be the number-one draft pick in the NFL, and I’d like you to manage me.”

McKee was out of her depth. She knew she was out of her depth. But Jackson wasn’t looking for a miracle worker. Just someone with his best interests in mind.

A few days later, McKee reached back out to Jackson. “O.K.,” she said. “I can help you as a manager. But you need a lawyer to handle contracts. Because there are things I don’t understand.”

McKee was friendly with a banker who did some work with Miller, Hamilton, Snider & Odom, a Mobile law firm that also had no experience in the world of athletics. A meeting was arranged, and what Jackson liked was the honesty. Jack Miller, the firm’s founder, didn’t try faking his way through the discussion with promises of a Toyota spot and 50-room mansion. “We didn’t know anything about sports law,” Miller said. “But we weren’t afraid of trying new things.” Miller told Jackson he would be represented under the traditional lawyer-client relationship, as opposed to taking a percentage of his earnings. Again, the honesty soothed Jackson’s psyche.

By now the NFL draft was one month away, so Miller got to work. He assigned Tommy Zieman, one of the firm’s partners and the former head of the antitrust section of the state attorney general’s office, to handle football; and Richard P. Woods, a firm employee and possessor of a tax degree, to take baseball.

Roughly three weeks before the NFL draft, Zieman traveled to Tampa to meet with Krueger and Ward Holland, the Buccaneers’ treasurer. Around the same time, Woods was trying to grasp Jackson’s baseball potential. The first pick in the upcoming major league draft belonged to the Pirates, who told Woods they loved Jackson and thought him to be a remarkable prospect—but the risk of losing him to the NFL was far too great. The one franchise that seemed willing to use a high selection on Jackson was the Angels, who had drafted him as a lark in the 20th round a year earlier. The team invited Woods and Jackson for a visit, and on April 21 they flew to Anaheim to attend a game.

Throughout his life, Jackson had responded to “Who’s your sports hero?” with “Reggie Jackson.” It wasn’t particularly deep—the common denominator being a last name. But now Mr. October was the Angels’ 40-year-old designated hitter, and on the field the two Jacksons met and shook hands for a photo op. A notorious egoist, Reggie told the assembled media that one day, with hard work, Bo Jackson could maybe become the next Reggie Jackson.

Bo walked off, never forgetting the arrogance. “Once I got to meet Reggie,” he said later, “I was sorry that we have the same last name. He is an a--hole.”

On Saturday, April 26, a mere three days before the NFL draft, Zieman and Miller sat with Culverhouse in Tampa. The Buccaneers’ owner wasted no time with pleasantries. “He was basically saying that unless Bo Jackson asked to play with them, they weren’t even going to make him an offer,” recalled Zieman. “Which is a strange way to deal with a Heisman Trophy winner.”

Zieman stressed to Culverhouse that baseball was a legitimate option, but he was met with dismissive laughter. Jackson was a poor kid from East Bumf---, Alabama. Was he really going to turn down millions of NFL dollars to stand in a minor league outfield and kick at the weeds?

“Culverhouse is a businessman, and one, I think, who only negotiates from a position of strength,” said Zieman. “But he clearly didn’t have that with Jackson, because Bo Jackson isn’t driven by the dollar. He’s driven by what Bo Jackson wants to do.”

As the draft neared, teams reached out to Tampa to see whether the No. 1 pick was available. The Buccaneers’ asking price, however, remained firm: two marquee players and a first-round draft choice, or three marquee players yet to enter their primes. “That,” said Leeman Bennett, the head coach, “is how we’re looking at it.”

It was a joke. Just as major league teams were reluctant to draft Jackson in the first round, NFL teams were reluctant to offer Tampa a king’s ransom. What if, say, the 49ers gave up cornerback Ronnie Lott, halfback Roger Craig and nose tackle Michael Carter—and then Bo wound up a San Francisco Giant?

The other problem for the Bucs: There was no Choice 1A. The consensus second-best player in the draft was Tony Casillas, an Oklahoma nose tackle who projected to be a solid-yet-unspectacular pro. Purdue quarterback Jim Everett had a strong arm, Alabama defensive end Jon Hand was a 6'6", 280-pound cinder block. But the Buccaneers could not make a serious case for bypassing Jackson for another Hercules. There was only one Hercules.

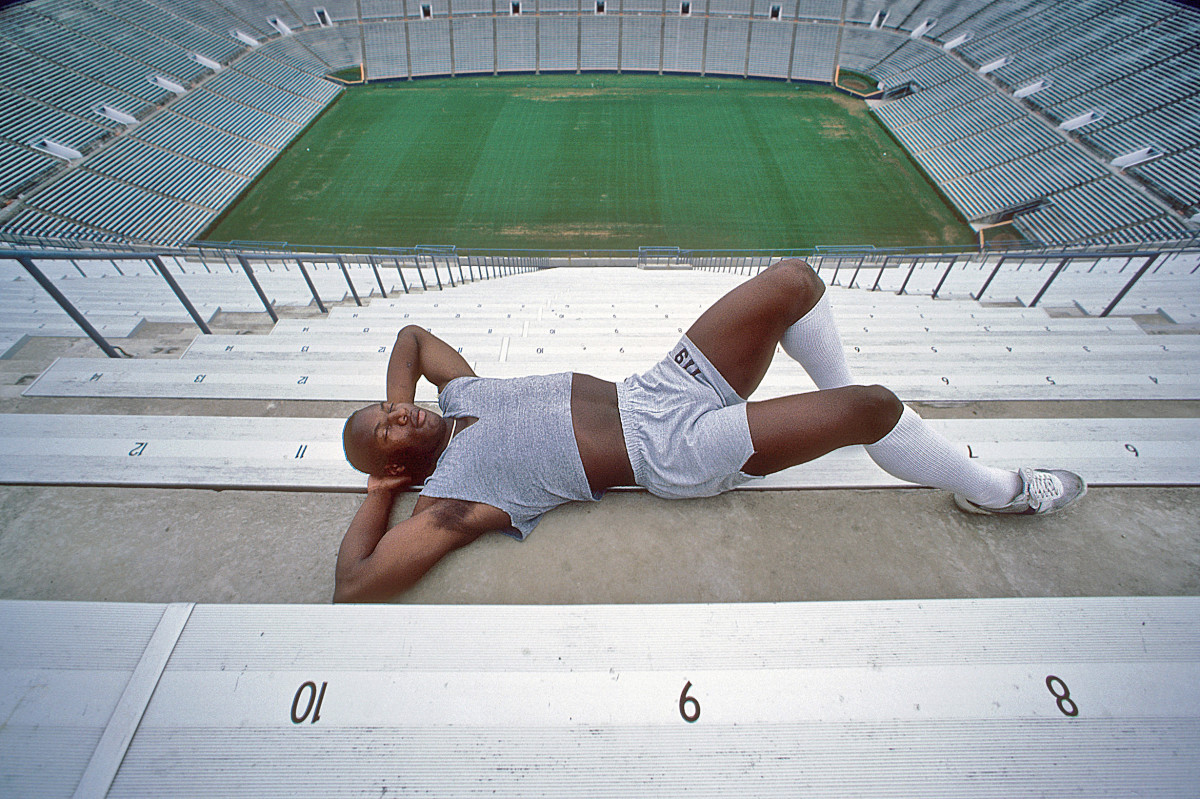

On the morning of April 29, Jackson and Zieman flew to New York City and a white limousine, sent by the NFL, ushered them from LaGuardia Airport to the Marriott Marquis, where the draft was being held that night.

The event began at 8 p.m. with Pete Rozelle, the league’s commissioner, first welcoming spectators, then announcing, “First pick, first round, Tampa Bay.”

Jackson, wearing a pinstriped gray suit and sitting backstage with Zieman, was nervous. He didn’t want to play for the Buccaneers, but he did aspire to be the No. 1 selection. So as the seconds ticked away, he could feel his anxiety building. Had he played this right? In Tampa, meanwhile, coach Leeman Bennett stared at the television before him at team headquarters. He repeatedly told Culverhouse that unless Jackson was a lock to commit, drafting him first would be a potentially historic blunder. “I was guaranteed we’d sign him,” Bennett said. “So I was O.K. with the idea.”

From the galley in New York, a soft chant turned loud: “Bo! Bo! Bo! Bo!”

Rozelle leaned into the microphone ...

“With the No. 1 pick in the 1986 NFL draft, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers select ... Vincent Edward ‘Bo’ Jackson, running back, Auburn University.”

Jackson and Zieman hugged, and the top selection walked to the stage to shake Rozelle’s hand. The commissioner gripped a football and said to Jackson, “This is the ball you want, Bo.”

“I’ll admit,” Jackson replied. “I can hit that better than a baseball.”

There was no Buccaneers jersey for Jackson. Culverhouse was nowhere to be found—the team was represented by Bob Thompson, a community college athletic director who was pals with the owner. Jackson turned down an immediate offer to fly to Tampa and meet with media and fans, but he was gracious. “I’m happy that the Buccaneers drafted me,” he said. “It’s nice to be the number-one player picked.”

Four weeks later, on May 28, Jackson (urged on by his representatives) agreed to give the Buccaneers something of a shot. He traveled to Tampa, held a quick press conference in Salon B at the Airport Hilton, then grabbed dinner with a handful of Bucs players. The next morning he had breakfast with former Tampa defensive lineman Lee Roy Selmon, went on a sightseeing tour with receiver Theo Bell and learned he was going out for an intimate lunch with just the owner and the team’s 24-year-old quarterback, Steve Young.

That was Culverhouse’s idea. He thought Young was an ideal recruiter. “You gotta sell him, Steve,” Culverhouse said before the meal. “Sell him on the future of this organization.”

“O.K.,” Young replied. “I’ll do my best.”

The Buccaneers had finished 2–14 in 1985, their third straight losing season. Their facilities were at a Division II college level. The roster was thin. The offensive line was a rotting slab of rank meatsicles. “There was nowhere worse to play,” says Ivory Sully, a veteran defensive back on that team. “They put us up in a motel that was worse than a Motel 6. They fed us terrible food. They didn’t care about winning.”

And Culverhouse, says Joe Henderson, a Tampa Tribune columnist at the time, “was a horrible human being. He cared about the bottom line, and nothing else.” Young, who had spent two years quarterbacking the Los Angeles Express of the upstart United States Football League, came to Tampa in 1985 and was thunderstruck by the incompetence. “I remember at one point I called my dad and said, ‘I think I’m just gonna go to law school,’” Young recalls. “‘I don’t wanna do this.’”

But with Jackson in town, Young had a task. The two athletes and the owner went to one of Tampa’s fancier steak houses, and after a few minutes Culverhouse looked at Young and said, “Let me leave you two guys to talk.” He excused himself and walked from the table. Within seconds, Jackson leaned in. “Hey, man,” he said, “I’m never coming here. Just so you know, there’s no f---ing way.”

Young smiled. “Well,” he replied, “I guess that ends my recruiting thing.”

Culverhouse returned, and neither player let him in on the discussion.

“Bo was correct in his instincts,” says Young. “You can be a losing team with a plan. You can be a losing team with direction. But the Buccaneers could not stop their own dysfunction. No sane person would choose to join that franchise.”

Later in the day, a handful of Buccaneers players took Jackson bass fishing on Lake Tarpon. Again, this was Culverhouse’s idea. The sun. The warm breeze. The comradery. Scott Brantley, a sixth-year linebacker out of Florida, was nothing if not blunt. “Bo,” he said, “we’d love to have you. But you do not want to be a Tampa Bay Buccaneer. This place is a f---ing joke.”

The baseball thing still felt far-fetched.

When asked, Jackson told media members that he was “50/50” as it pertained to the two sports. But with the Buccaneers’ all-around odiousness, the idea of shocking the system gained momentum. That was Bo Jackson in a nutshell: He gravitated toward the unexpected. Though never particularly rebellious, he believed in walking his own path, expectations be damned. So as the weeks passed and the inevitability of his NFL future seemed near-certainty, a turn toward baseball felt increasingly alluring.

On May 19, Jackson and Woods traveled to Toronto to meet with Pat Gillick, the Blue Jays’ general manager (“I’m here visiting and looking for a job,” Jackson told Canadian reporters), and later that month Woods returned to Anaheim to break bread with Mike Port, the Angels’ GM. Both franchises were genuinely interested in Jackson, but they remained concerned about wasting a valued pick on the Buccaneers’ future halfback.

After returning from the West Coast, Woods was in his office when Baird, the Auburn baseball coach, called. A former Royals prospect, Baird retained close ties with the organization. In particular, he was in contact with Kenny Gonzales, the scout who had tracked Jackson dating back to high school.

Baird knew how high Kansas City was on Jackson, and he urged Woods to reach out to Art Stewart, the Royals’ scouting director. Although Stewart never saw Jackson play, he gobbled up Gonzales’s reports. The scout was of the belief that Bo Jackson—five-tool megaprospect—was the (potential) second coming of Mickey Mantle. Hence, Woods and Stewart spoke, and the conversation concluded with Jackson’s being invited to Kansas City for a predraft meeting.

On the afternoon of May 30, Jackson and Zieman arrived in Missouri and headed down to Royals Stadium for a matchup against the Rangers, where Jackson was introduced to Stewart and John Schuerholz, the general manager. Schuerholz had visited Auburn to watch Jackson play as a college junior, and he was overwhelmed by the power-speed combination. But this all felt ridiculous. “I think we’re being used,” Schuerholz said to Stewart shortly before Jackson’s arrival. “I think we’re being used for leverage they can use in football.”

Across the long history of American sports, hundreds of agents have worked teams against teams and leagues against leagues. Within the previous few years the Royals had drafted three college football standouts: Stanford’s John Elway, Pittsburgh’s Dan Marino and Florida State’s Deion Sanders. None wound up in Kansas City.

So, shortly after Jackson stepped through the front doors, Schuerholz sat him down for a one-on-one.

“Bo,” he said, “do you really want to play baseball?”

“Yes, I do,” Jackson replied. “That’s why I’m here.”

“You’re not using us for leverage?” Schuerholz asked.

Jackson looked him straight in the eye.

“Mr. Schuerholz,” he said, “that is not something I would ever do.”

A few minutes later, Jackson was escorted onto the field to observe batting practice. One year earlier the Royals had won the World Series via speed, defense and pitching. Only a single player, third baseman George Brett, cleared 100 RBIs, and only two (Brett and first baseman Steve Balboni) had at least 30 home runs. Watching Kansas City’s players swinging away, a sly grin crossed Jackson’s face. “Hey, Art,” he said to Stewart. “Not a lot of these guys hitting the ball out of the park, huh? This looks easy.”

Jackson zeroed in on the outfielders, who were throwing balls back into the infield. “Hey, Art,” he said. “These guys don’t throw so good. I could throw better than that.”

It was cocky—but, Stewart thought, good cocky.

After BP, Jackson strolled into the home clubhouse, where players were at their lockers preparing for the game. He shook hands with pitcher Bret Saberhagen and DH Hal McRae. George Brett, the team’s biggest star and a die-hard football fan, introduced himself to Jackson. When it was time for Jackson to leave, Brett yelled out, “Good luck in football, Bo!”

Jackson stopped, spun and headed straight toward Brett. He pointed a finger in the superstar’s face and roared, “Don’t you bet on it!”

On the night before the MLB draft, Richard Woods called John Schuerholz with some great news: The Royals were Bo Jackson’s preferred baseball destination. And by now it was clear that Jackson was not going in the first two rounds. The risks were far too great, and many (including Schuerholz) remained skeptical.

Held via conference call, that draft began with the Pirates selecting a University of Arkansas infielder named Jeff King. Inside the Royals’ draft room, the uncertainty was agonizing. Gonzales, the scout whose life was now largely devoted to all things Bo, swore Jackson would never sign with the Buccaneers. “You have to understand,” he pleaded with Stewart, “he hates them. Passionately. He wants to play baseball, especially if it’s for us.”

“Do you think anybody else knows what you know?” Stewart asked.

“Definitely not,” said Gonzales.

The Royals used their first pick (24th) on Tony Clements, a high school shortstop who would never pan out. The opening round passed without Jackson being selected, then the second and third rounds. Kansas City was playing a dangerous game of greatest-athlete-anyone-had-ever-seen chicken. As were the Angels and Blue Jays, clubs equally interested and terrified. As the fourth round began, Stewart looked at Schuerholz and said, “If we blow the fourth-round draft pick with Bo Jackson, the franchise is not going to fold.”

With the 103rd pick, in the fourth round, the Angels tabbed ... Paul Sorrento, a Florida State outfielder.

Deep breaths.

With the 104th pick, in the fourth round, the Cardinals tabbed ... Mark Guthrie, a pitcher out of Louisiana State.

The Royals’ draft room broke out in cheers.

As soon as the noise dimmed, Stewart leaned into the phone and crowed, “The Royals select Vincent Edward Jackson, outfielder, Auburn University. Better known as Bo.”

Most players hoping to be drafted would be sitting by the phone. Not Jackson. Most players hoping to be drafted would demand their agent reach out ASAP. Not Bo. Most players hoping to be drafted would be overcome by stress and drenched in sweat. Not Bo. He was in San Juan, Puerto Rico, scuba diving with friends. There was no phone or television nearby.

Jackson returned to Auburn the next day. A classmate spotted him in the Sewell Hall cafeteria and congratulated him on being tabbed by the Royals.

“I was?” Jackson said.

“Yup, you sure were.”

Jackson called Woods, who confirmed the good news and arranged a series of remote interviews with Kansas City’s television stations. “The kid was on cloud nine,” Woods said. “Up to that point, I would’ve bet that he would play football. I didn’t know what he’d do—I don’t think he made a decision—but because of how happy he was, I felt there was a great likelihood he’d play baseball. He was thrilled by getting drafted by the world-champion Kansas City Royals.”

More than a month had passed since the NFL celebrated Jackson as its No. 1 pick, and the Buccaneers had yet to make an offer. On the day his team took Jackson, Culverhouse had promised reporters that “if it’s a matter of money, I know we’ll win. We’ll make him the highest-paid player ever taken.”

On June 13, Zieman and Miller flew to Tampa to sit across from Culverhouse. They had already told the Buccaneers they had no interest in swapping terms. They wanted the team to put its absolute best offer on the table. But these were the Buccaneers. Instead of presenting firm financial figures, they broached the topics of drug tests and skill guarantees. It was exasperating. When Zieman said any offer would have to be run by Jackson, Culverhouse snickered. “That’s not the way agents do things,” he said.

“No,” Zieman snapped, “but it’s the way lawyers do things.”

One day later, Tampa Bay presented its offer: $4 million over five years, including a $1.5 million signing bonus ($1 million as an annuity that would kick in by 1998). An accompanying list of incentives could, at best case, bump the deal’s value up to $7.6 million. On the bright side, it was an enormous jump from the four-year, $2.6 million deal the top selection in ’85, Virginia Tech’s Bruce Smith, landed with Buffalo. Zieman asked whether the Bucs could increase the numbers, to which Phil Krueger replied, “I could probably get it bumped up a few more dollars.” Moments later, having conferred with the owner, Krueger said, glumly, “I went to talk to Mr. Culverhouse, and Mr. Culverhouse said, ‘I won’t raise it a penny.’”

To Jackson, none of this was surprising. From the day he lost his college baseball eligibility, he viewed Culverhouse warily. He didn’t trust him, didn’t like him, didn’t want to play for him. “Culverhouse put an offer out, and I said, ‘No, I don’t want it,’” Jackson later recalled. “You’re going to have to pay through the nose. I’m the first player taken in the draft, I’m the Heisman Trophy winner and I think I should name my price. You let everybody else name their own f---ing price, so why can’t I name my own price? Is it just the color of my skin?”

When Jackson ultimately rejected the offer, Culverhouse threatened to cut it in half. “And,” the Bucs owner said, “you won’t have a f---ing choice.”

In a peculiar way, Jackson loved this. Loved. The franchise he wanted nothing to do with was making his decision simple. “I told my lawyer to tell Culverhouse to go f--- himself,” Jackson said. “And then when it was all said and done he pissed one of my lawyers off. My lawyer just got up and went to leave and then before he left he said [to Culverhouse], ‘Now I see why you are such a tough person to work for. Because you’re such an a--hole.’”

The Royals, on the other hand, were honest and upfront: $850,000 for three years, with options to leave baseball if Jackson returned part of his salary.

The Buccaneers had offered four times more than the Royals. They were already sending out mailers featuring Jackson’s photograph to potential season-ticket buyers. Woods stressed this to Jackson—not in an effort to lure him toward football, but to make clear that a kid who had grown up wearing only socks to elementary school was turning down a lot of money from an organization that would centerpiece him. Jackson was unmoved. “I’m not interested in anything Hugh Culverhouse has to say, offer or anything,” he said. “And that’s that. … The old c---sucker.”

On June 20, Jackson and Woods flew to Memphis, home of Avron Fogelman, Royals co-owner and owner of the Memphis Chicks, Kansas City’s Double A affiliate. Woods, Fogelman, Schuerholz and Ewing Kauffman (the Royals’ majority owner) negotiated deep into the night as Jackson snoozed in a nearby chair.

The final offer boosted Jackson’s earnings to $1,066,000. It also included two guarantees: (1) that Jackson would start his career no lower than Double A; and (2) that he would be called up to the majors before the end of the 1986 season.

Around 11:50 p.m., Woods looked at Jackson and asked, “Are you ready to sign?” Jackson smiled and said, softly, “I sure am.”

Told the next day of the decision by Zieman, Culverhouse didn’t scream or laugh or cry. He simply pulled out a cassette tape and played the recently released Dionne Warwick, Elton John, Gladys Knight and Stevie Wonder song “That’s What Friends Are For.” He said it gave him the proper perspective. Or something weird like that. “Keep smiling, keep shining, that’s what friends are for,” he told a (surely bewildered) reporter. “I don’t think we’re bums in this case.”

The Tampa Bay Buccaneers—bums in this case—were left with nothing to show. Bo Jackson chose baseball.

• He Survived a Shooting at His High School. Returning Has Been, at Times, Unimaginable

• James Wiseman Is in a Golden State of Mind

• All Eyes on Zion Williamson