For Jalen Hurts, This Is All Routine

The MVP candidate is everywhere, but while everything is different now, it’s always the same him. His face is blank and expressionless, whether on the mirrors lining a wall in a small space adjacent to the Eagles’ locker room, or on the TV nearby, where he’s building a candidacy no one else expected.

It’s always the same look with Jalen Hurts, even after touchdowns: stoic, intense, firm and unfeeling; his countenance so consistent that it might seem like an act, an I-work-too-hard reply to the what’s-your-biggest-weakness question at a job interview. But here he is now, the real him—same face, same demeanor, same everything—sitting atop a swivel chair on a Friday afternoon in mid-December.

For a man whose own brother refers to him as “The Robot,” even a routine haircut is anything but. Because this is Hurts, the doubted-but-never-deterred Eagles quarterback, his eyes scan for holes in his preferred fade. They spot tiny imperfections, mistakes the size of a needlepoint, while signaling the makeup of a man who wears a cloak of self-assuredness. Hurts doesn’t simply get his hair cut; he directs the barber like he orchestrates the lethal offense of a Super Bowl contender. Right there. Little higher.

At this point, it’s two days before Hurts and the Eagles will play the Bears in Chicago. Win and Philadelphia will move closer to locking up the NFC’s No. 1 seed. Everything—his fade, his season, his career—is going exactly as planned. At least for another 48 hours.

As “Big Pimpin’” booms in the background, Hurts tries to explain his 2022 campaign, the one that demanded recognition of his value and followed a time that he refers to as “everything else.” He makes the evolution sound simple, the product of glorious-and-infamous-and-indicative events and how they shaped him; the goal, no more than continuous improvement; progress born from process, the routine bolstered and advanced but the soul unchanged since middle school.

He pivots into values: consistency, persistence, patience, diligence, accountability. They are not revolutionary. But Hurts isn’t spewing buzzwords for consumption. Nor is he, as often labeled, “emotionless.” He’s principled, unwavering, mindful and intentional, a throwing-slashing-running-spinning-escaping-and-scoring embodiment of the famous Shakespearean phrase, “to thine own self be true.”

Bzzzzzzzzz. The clippers interrupt the silence, as Hurts displays the self-awareness that helps him both recognize and reconcile the gap between how he sees his value and how a significant portion of football types appraise him. He might not discuss the more egregious takes—the Madden rating of 74 before the season, the notion that his success owes to his teammates and not the other way around—but he’s aware of them. In fact, he stores them. Not, he says, in a notes file, or on a bulletin board, but in his head.

The doubts that morph and shift no matter how many times Hurts proves “them” wrong only exacerbate his problem. They assume he should see his career, accomplishments and trajectory in a certain way. But most assumptions cap well below what Hurts himself believes is possible. “There is no arrival,” he says, deploying air quotes. “The eagerness, the thirst, the desire to want more will always be there.”

Hurts doesn’t dodge uncomfortable questions. He pushes back. He clarifies. The storage of the slights against him isn’t personal, he says. He has forgiven but will never forget. He welcomes dissenting opinions, as long as critics/skeptics/nonbelievers “stand on” them later. He mentions a favorite phrase to explain all this: Everybody and they opinions don’t deposit at the bank, meaning they don’t matter, not really, not compared to the plan.

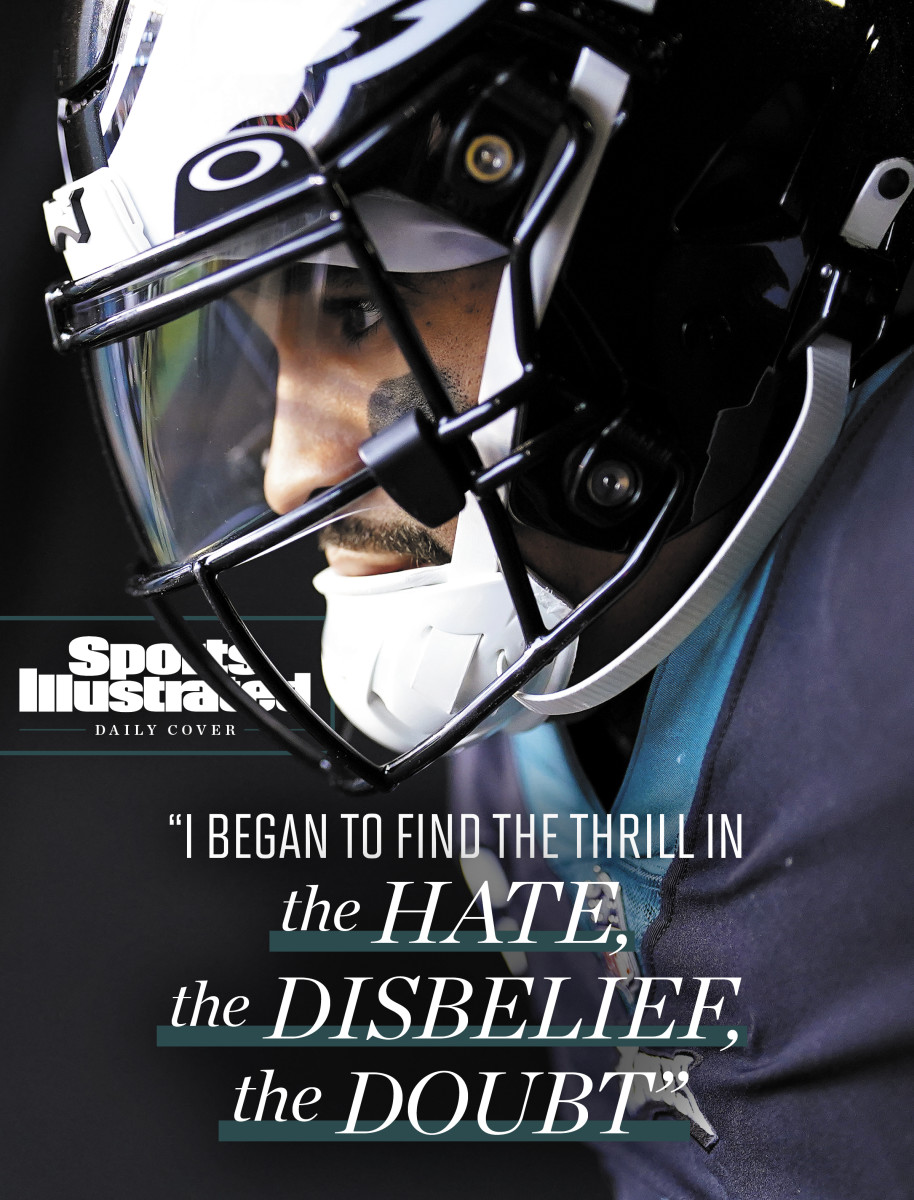

Bzzzzzzzzz. “I carry those scars on me everywhere I go,” Hurts says. “I began to find the thrill in it. I began to find the thrill in the hate, the disbelief, the doubt.”

What does that mean? “The thrill is [it has] been that way forever. There’s a thrill in not being satisfied, honestly. Whether you like what I’m doing or not, I’m not satisfied.”

He’s rolling now, with fewer pauses and more urgency. He “hates” talking about himself, but when he doesn’t speak in depth—which happens for long stretches—his actions and words are often assigned motivations. He’s told what he meant. Life has always been this way, a mix of odd doubts and uncommon drive, one fueling the other and both ever-present. Closing this gap doesn’t interest him. The plan does. That’s his superpower, his separator, this singular approach. Bzzzzzzzzz.

“My swagger,” Hurts says, “is to be myself.”

Earlier on that Friday afternoon, inside an empty Eagles weight room decorated with holiday lights, a Christmas tree, Santa statues, two Pop-a-Shot machines and a Super Bowl banner from the 2017 season, Hurts plays deejay for an audience of five. A splendid mix of R&B, mostly from the 1990s, transports onlookers back to middle school dances. (Sadly, the 24-year-old refers to this mix as “old school.”)

Let’s make it last forever, Keith Sweat croons.

The rain-sleet-light-snow falling outside is fittingly frightful. But while all but one teammate have already sped home to their families or their couches, Hurts warms up with resistance bands under the supervision of Ted Rath, the Eagles’ VP of player performance. “As a young QB, he’s the best leader I’ve been around,” says Rath, who’s now with his fourth NFL team. “He’s like Sean [McVay, the Rams coach] that way. Totally immersed.”

Hurts jumps into lifting sessions with the offensive linemen and sometimes pushes heavier amounts. He’s always the last player working out on Friday afternoons, there three to four hours after the majority of his teammates, Rath says. And after games, when Rath sends Hurts text messages, short directives like make sure we stay grinding, Hurts sends photos back of feet and televisions, both his. He’s already watching game film of his next opponent.

Profile stories of sports stars long ago turned late-workout scenes into eye-rolling clichés. But, in this instance, the cliché is also the man. There’s no separating them. Rather than an act, everyone who knows Hurts, who understands what propels him, agrees that what makes him typical also makes him atypical, because of the totality of his commitment.

When Eagles executives dispatched Rath to Alabama’s campus before the 2020 draft, one story stood out above all. On the morning after Nick Saban benched Hurts for Tua Tagovailoa at halftime of the national championship game in early ’18, the quarterback showed up at the Crimson Tide’s weight room for a scheduled lift. His job might have changed in an acutely public and uncomfortable way. But rather than sulk or sleep in, Hurts showed up, only to notice freshmen screwing around. He gathered them. “This is not how we do things at Bama,” he said, voice rising. “We have a standard to meet.”

Almost five years later, on this afternoon in mid-December, the who of Hurts has changed. The quarterback once synonymous with the half he didn’t play; who transferred; apprenticed under Carson Wentz; “competed” with an ancient version of Joe Flacco; ranks among the NFL’s best players.

This Hurts is one of two front-runners, alongside Patrick Mahomes, for league MVP. He ranks among the most efficient passers and best deep-ball throwers in the league. From weeks 5 to 14, he ranked first in total touchdowns (24), touchdown-to-turnover ratio (8.0), passer rating (112.4), third-and-fourth-down completion percentage (71.7) and passing scores of 20 yards or more (11). Before he was held out of two late-season games as a precaution after sustaining a shoulder injury, he was on pace for the first NFL season in excess of 4,000 passing yards and 800 rushing yards (he finished with 3,701 and 760 over 15 games).

Many view the past four months as an “arrival.” Hurts disdains that notion. He sees something else—several things, actually, all resulting from a wider, longer view. A higher comfort level owing to consistency with coaches. A lower body-fat percentage (8.5). Gratitude. Processing speed. Experience. Elite wideouts. The NFL’s best offensive line. Bright coaches. Plus, an offseason tune-up with the quarterback wizards at 3DQB. He’s handing out credit like TD passes, right up until … he stops.

Watch the Eagles with fuboTV. Start your free trial today.

He cites the narratives attached to him: defensive, guarded, sometimes prickly. He begins an exercise he usually avoids. He starts picking them apart, choosing his words carefully. “If somebody else were to … people jump quick to give … people are just surprised by something”—meaning surprised by him—“for whatever reason. They love giving credit for your success.”

The workout continues. Chest presses. Core rollouts. Functional-hamstring exercises. Air squats. Weights clang. Hurts grunts. Hurts grimaces. The TV over his left shoulder shows him slicing up a defense, beelining toward the end zone. The sign over his right shoulder reads Merry Christmas. He doesn’t so much as glance at either. He’s lasered, singular in focus, eyes trained straight ahead as the blood flow in his legs is restricted by a medieval contraption.

Sweat continues to serenade. Let’s make it last forever. Well, yeah, that’s the plan.

Hurts leans forward, as if for emphasis. His eyes radiate that trademark intensity. Having long ago challenged the sunrise for consistency—naps every afternoon after school, Popeyes excursions every Tuesday, Friday nights spent as a ballboy for his father, Averion Sr., a Houston-area high school coach—he wants to make the patterns clear. That goes for how he defines himself, by fixed routines, and for how others define and mischaracterize him. “Always been a robot,” says his older brother, Averion Jr. “Always very habitual.”

Senior brought both boys to practices, in part as a chance for free childcare. He gave them a single edict—don’t break anything—and, starting in fifth grade, allowed them to hop into drills and listen in on meetings. Senior remembers Jalen setting up in his office and just sitting there, silent and stoic. Jalen never interrupted, so his dad never asked him to leave the room. “Never thought he was paying attention,” Senior says.

Jalen persisted, in part because he was absorbing his father’s love of football, which was most evident in how deeply he resonated with his players. In his first year of youth football, the future MVP candidate played offensive line, defensive line and tight end. (Dad’s review? Terrible.) The following season, Jalen switched to quarterback, purely out of necessity.

Senior didn’t tolerate any nonsense on the field. He expected the boys to listen and never talk back; to work, even harder than their teammates. The combination, he hoped, would lead to continuous improvement. “Because the one thing I understand as a coach is there’s a bunch of kids that are more advanced, literally,” he says. “But it’s not like they just keep getting better and better and better and better throughout the rest of their lives.”

There’s only one problem with that theory. Jalen did. At Channelview High, he mastered an offense that married the spread’s soul and Air Raid tendencies. He became the starter in his sophomore season, then elevated the next fall into the stratosphere reserved for elite, but not universally agreed upon, recruits. “Junior year, he was a different dude,” Dad says.

Senior remained honest, both with Jalen and himself. The kid could play. He displayed a rare combination for a quarterback: big enough, strong, yet nimble and athletic; not the fastest runner but “subtle in his shiftiness”; consistent and driven and robotic as all hell. The uninitiated “didn’t expect” the show that Jalen put on every week, his father says.

Expect. That word and all its variations bubble to the surface often in the Jalen Hurts story. The player stars, leads, wins. The perception of the player is mostly positive. But evaluators waver, too. Senior calls this Jalen’s propensity to produce unexpected positive results, which sounds like a backhanded compliment but is grounded in his always-honest approach.

Hence the doubts, which started around then. For all the attention paid to Jalen by major college powers, some of his favorite programs openly wondered about his throwing ability. Dad went so far as to summon the offensive line for meetings with visiting college coaches, so they could see an undersized offensive line up close. Perhaps this uncertainty is what Hurts refers to when he says he has “been through experiences that not many people would have been able to endure.” He passes on a follow-up question, declining to elaborate.

As always, the who of Hurts speaks for him.

Qualms from outsiders notwithstanding, The Robot landed a scholarship at Alabama. Football, he says, would never define him. Routines would. Principles would. Habits would. He would.

Hurts committed in the summer of 2015, despite another odd duality. He chose the Crimson Tide over programs like Texas A&M and Mississippi State, major powers all. But his mailbox wasn’t crammed with offers. Seven months later, he moved to Tuscaloosa, Ala. He was 17 and yet already certain of his future on horizons near and far. He would start for the defending national champions, winner of four of the previous seven titles, in his true freshman season, as a teenager, for the exacting demigod Nick Saban, no problem.

By Alabama’s second game in 2016, Hurts was starting. No problem, indeed. He led the Fighting Sabans to 11 straight wins, then led Alabama to victories in the SEC championship and over Washington in the College Football Playoff semifinals. Saban sometimes wondered why Hurts never reacted after poor reads or errant throws, according to DeVonta Smith, Hurts’s teammate in college and the NFL. But this would be more important than any of them realized. Clemson would triumph over Alabama in the national championship game. Teammates looked to Hurts to gauge his reaction. He wouldn’t pin the defeat on anyone else. He wouldn’t change. He would accept responsibility, get right back to work.

The next month, in early 2018, the Eagles won Super Bowl LII over the Patriots. But Hurts could not recall whether he caught the Philly Special or not. It’s more likely that he skipped the game in favor of working out.

Still, the narratives Hurts hates continued taking shape. He was a running quarterback who would never be an elite thrower of footballs … he threw to a bevy of future NFL stars … he moved, not slowly but also not quickly enough, through his progressions … he didn’t project as an NFL star. Never mind that factors like age, statistics and track record dismissed many of those misgivings outright. After the national championship game benching, his backup’s signature victory and morning missive in the weight room, Tagovailoa won the starting job. Rather than one future NFL starter beating out another future NFL starter, this seemed to solidify every story line, whether fair or accurate or neither.

His son didn’t transfer, sulk, become an anonymous source, create a locker room schism or change the ethos he intentionally cemented. Instead, in the same city (Atlanta) and same stadium (Mercedes-Benz) where his benching made international news, Hurts subbed for an injured Tagovailoa and saved Alabama’s next season by directing a comeback over Georgia in the conference championship. Couldn’t throw? Against the same defense that flummoxed a hobbled Tagovailoa into more misfires than completions and two picks, Hurts came in, cold, and went 7-for-9, throwing for the tying score and dashing in for the winning one.

Hurts still didn’t change, but neither did his situation. Tagovailoa regained his job, lost in the national title game and would clearly remain the starter for Hurts’s senior season in 2019. So Hurts transferred to Oklahoma, wanting to play for quarterback whisperer Lincoln Riley, win more games, command another locker room and prove he could play in the NFL. He completed nearly 70% of his throws, threw for nearly 4,000 yards, tossed 32 touchdowns against eight interceptions and won 12 games. Riley aided his development, specifically with reads and accuracy on deep passes. “Unwavering,” Jalen’s brother says of his mindset. “Just confirmed everything I knew.”

Averion Sr. believes Jalen proved, over and over, his “propensity to learn.” Surely that would carry over into the NFL. But one question they could only influence and never fully control lingered, same as always: Would everybody see what they saw?

Whether Sweat, Tevin Campbell, K-Ci & JoJo; or earlier musicians like Al Green, The Isley Brothers or Frankie Beverly; soulful R&B forms the soundtrack of Hurts’s routines. This sentiment also applies to his existence, since they’re really the same thing. The genre preference comes from his parents, especially his mother, Pamela, an educator who tuned the family radio whenever possible to old-school Majic 102.1.

In some ways, Hurts’s listening habits are their own routine. Through the instability of the past six years, whenever he feels scattered he turns to music. This is how, he says, “I find peace.” There’s a glint of a smile as he says this, a crack in the stoic armor.

His father was right, by the way. He did carry his spirit into pro football. He even adopted a motto that Alabama motivational guru Kevin Elko told him well before the benching: You were born for the storm and built to overcome.

Wouldn’t conquering the NFL start in the same place? Yes, as long as Hurts followed the plan. After Philadelphia drafted him in the second round, he kept adding—skills, proficiency, mastery, techniques. He started writing out gratitude lists most mornings to focus on what mattered (grandma, teammates, positive interactions).

Before his rookie season, Hurts focused on learning the Eagles’ offense, until he understood every intricacy in every variation of every play. He organized dinners for various position groups, invited teammates to VIP events and began corresponding with three like-minded Eagles legends. The evolution of the quarterback position—and the Black quarterback’s place within it—could be traced from Randall Cunningham to Donovan McNabb to Michael Vick to Hurts.

Still, Hurts’s Eagles career began in the same place his Alabama tenure ended: as a backup, now to Carson Wentz. Hurts displayed mastery of the offense in spot duty, the kind born from bonds strengthened and that sunrise consistency. He started Philly’s last four games. But whether inactive in Week 1 or scuttling over the final month, the blank expression remained. “He’s always been naturally stoic,” his older brother says. “It’s frustrating … you never know what he’s thinking.” And yet, also perfect, for a scrutinized quarterback playing in a tough sports town, having overcome so many doubts already but nowhere near eradicating all.

After his rookie year, the Eagles ushered out Doug Pederson and brought in one of the league’s beautiful-mind types in Colts coordinator Nick Sirianni. This meant yet another coach swap for Hurts, same as with offensive coordinators in every season at Alabama. Would it ever end?

Hurts didn’t ask himself such questions, their nature antithetical to his bearing. Instead, he focused on speeding up his processing speed. At 6'1", he wasn’t short but also wasn’t classic-franchise-quarterback tall. The faster he recognized coverages, the better he could manipulate defenders. His style, best case, could be built to resemble a quarterback like Steve Young. Game reps helped there, but Hurts also intensified his studies, focusing on recognition and reaction, hoping that, by improving both, he would find more consistency. He did that while learning (yet another) new offense.

He also speed-dated (yet another) coach, meeting regularly with then 40-year-old Sirianni at team headquarters or restaurants or with the coach’s wife and three children. Sirianni had brought Brian Johnson, then 35, with him, putting Johnson in charge of quarterback development. Averion Sr. once coached Johnson at Baytown Lee High and welcomed him back for summer workout programs, before Johnson starred at Utah, setting a record for most wins by a quarterback (26) in program history. Senior had played high school ball against Johnson’s father. Between Sirianni, “Coach Brian” and offensive coordinator Shane Steichen, Hurts could continue his development under three of the brightest young offensive minds in football.

As those relationships grew, Hurts began joining the Tuesday- and Friday-morning game-plan meetings for Eagles offensive coaches. Midway through 2021, he started to suggest plays. Initially he didn’t want to overstep. But as he played more—and played better, upping his completion percentage, passing yards and every advanced statistic imaginable—his comfort level heightened. He attributes all gains to an authenticity, the who in Hurts that cannot be faked, let alone changed.

Hurts is ready to wrap on that Friday in December. The turbulence of last offseason—an underwhelming performance in a playoff loss in Tampa that gave renewed vigor to those questioning his long-term viability as a franchise quarterback—seems distant in relation to the season itself.

Overcoming, yet again, started in the same place, with the same approach. Hurts traveled to Florida to partake in training sessions hosted by right tackle Lane Johnson, who, Hurts says, “souped-up” a space outside his expansive residence near Fort Lauderdale until it resembled muscle barn, not beach.

He jetted to California to work with Adam Dedeaux at 3DQB. They concentrated on fluidity, to make him less robotic. Hurts seemed at his best when playing more like Aaron Rodgers, by using a natural creative flair and strong-enough arm to fling footballs all over the field. His baseball background helped create distinct arm angles, which meant fielding drills and other nontraditional methods. “He’s hard to please sometimes,” Averion Jr. says. “But that was pretty dope.”

The Eagles, considered a fringe playoff contender, won their first eight games. Hurts entered the MVP discussion. He won over the notoriously fickle Philadelphia sports fans. He started to draw comparisons to Tom Brady, based on obsessions with routines, plus their starting careers as backups, displacing veteran starters, sudden rises and the rest. The comps were optimistic but not a pipe dream. Brady can have his avocado ice cream. Hurts has his playlists.

After their first loss, to Washington in mid-October, the Eagles’ offense took flight. From weeks 12 to 14, they scored at least 35 points. To DeVonta Smith, how they won mattered most, because that stretch showcased a complete offense and a complete team. Not to mention a complete quarterback. Hurts ran for 157 yards against the Packers. He passed for 380 yards against the Titans. He threw for two scores and ran for another against the Giants, good for nine touchdowns in that span.

The Eagles, meanwhile, morphed into a trendy pick for Super Bowl champion. Philly played so well, in fact, that another chorus of doubts grew. Now, Hurts allegedly owed his success to his teammates, the elite offensive line and wideouts like A.J. Brown and Smith. McNabb says to simply look at the numbers. The quarterbacks who receive more credit, many of whom are surrounded by similarly deep rosters, are not dissimilar. “There’s no reason he shouldn’t be talked about like [them],” McNabb says. After all, their quarterback and his stoic, robotic personality tied everything together.

Near-disaster struck in Chicago. Hurts was off in a game the Eagles perhaps should have lost (three turnovers, defensive breakdowns, a missed field goal late). But he scampered in for three touchdowns and threw for 315 yards. He also sprained his right shoulder from a turf-slamming hit in the third quarter. Hurts still finished the game and the win. Philadelphia lost its next two with Hurts watching from the sideline and arriving for one game (Week 17) dressed as the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

Funny enough, but the nebulous doubters turned their misgivings away from Hurts and toward the Eagles. Some even called for him to win MVP, because his value was even more striking in his absence. Hurts proved them right when he returned for the regular-season finale, just in time to beat the Giants and snag the NFC’s top seed.

Vintage. All of it. Anyone who thought Hurts might change, rush back, ignore his principles or anything else hasn’t been paying attention. He was exactly the same.

McNabb thinks the Eagles are “one or two years away” from truly contending for the Lombardi Trophy. He doesn’t want to add any additional pressure on Hurts but says “they have the right guy to be an elite team.” Maybe he’s wrong. Maybe they already are. Hurts declines to “deal in hypotheticals” but says, only, “I know it doesn’t happen overnight.” He would know.

Hurts appreciates the sentiment and understands the root of the critiques. His evaluation is robotically clinical. “For a long time,” he says, “I’ve been a polarizing figure.” But he never deviated from the plan, and that’s the thrill. Right there. Doing exactly what he wanted, regardless of whether one person believed or one million people did.

To thine own self, right?