Fletcher Cox? ‘He’s a Hall of Famer, Hands Down’

A few years back, as Jim Washburn drove north from Dallas toward the coolest ranch he’d ever seen, he couldn’t help but consider the man who owned it. Fletcher Cox was born in Yazoo City, Miss. But limited? He was not. He high-jumped. He sprinted on relay teams. And he didn’t play football so much as he wrecked football games.

After 90 minutes, Washburn pulled onto the property. He scanned the 1,000 or so acres: the 7,000-square-foot-lodge, the exotic animals, the skeet shooting grounds and horseback riding trails and private cabins. He had never seen so many cattle. Nor an off-season retreat that came with a staff. Nor that many animal heads stuffed and hanging on every wall.

At that moment, he thought the only things any reasonable person would think: (1) This is beautiful, and (2) He’s already got the rest of his life down.

What a story. Cox grew up mired in poverty. He lost Shaddrick “Trell” Cox Sr., his older brother, to a heart attack at 34. But … football. He played the game with the same hunger he felt deep inside his belly, starring at Mississippi State and rising up NFL draft boards.

The Eagles dispatched their defensive line coach, Washburn, to take a closer look. It was 2012. Philadelphia held the 12th pick in what would be head coach Andy Reid’s final season sneaking cheesesteaks. Washburn took three visits, hitting the road to see Michael Brockers (LSU), Alameda Ta’amu (Washington) and Cox, who worked out for him on his school’s practice field.

Cox told Washburn he weighed 294 pounds. If true, Washburn laughed, he was the biggest person at that weight that Washburn had ever seen. They also went to dinner. They talked guns and Mississippi and football and dreams. Washburn decided on that trip: Cox wasn’t just good, he was perfect. Smart. Hungry. Strong. Balanced. Quick. Agile. The Eagles prayed he’d last and, when he did, they drafted him.

What happened next speaks to Cox’s drive and the Eagles’ history. Near the end of his 11th season, he has played 173 games, made six Pro Bowls and racked up 65.0 sacks despite rushing primarily from the inside. He ranks near the top of any ranking of this generation’s best defensive tackles. He also represents a through line from the Eagles’ last Super Bowl team to this one.

“He’s a Hall of Famer, hands down,” Washburn says. “There were two or three years there where he was the most dominant defensive player in the league. It’s a no brainer.”

TO WORK AND WIN IN PHILLY…:

According to three men who know the landscape well from their time with the Phillies. A brief oral history, told in stages, by Larry Bowa (player, manager, World Series champion), Charlie Manuel (manager, World Series champion, Phillies Wall of Fame) and Ruben Amaro Jr. (Philly native, player, general manager).

The Basics…

Charlie Manuel (CM): Fans in Philadelphia are so serious. About the Eagles, the Phillies, the Sixers, the Flyers. All of them. You take some criticism. But once you start playing, especially when you start winning, they just absolutely fall in love with you.

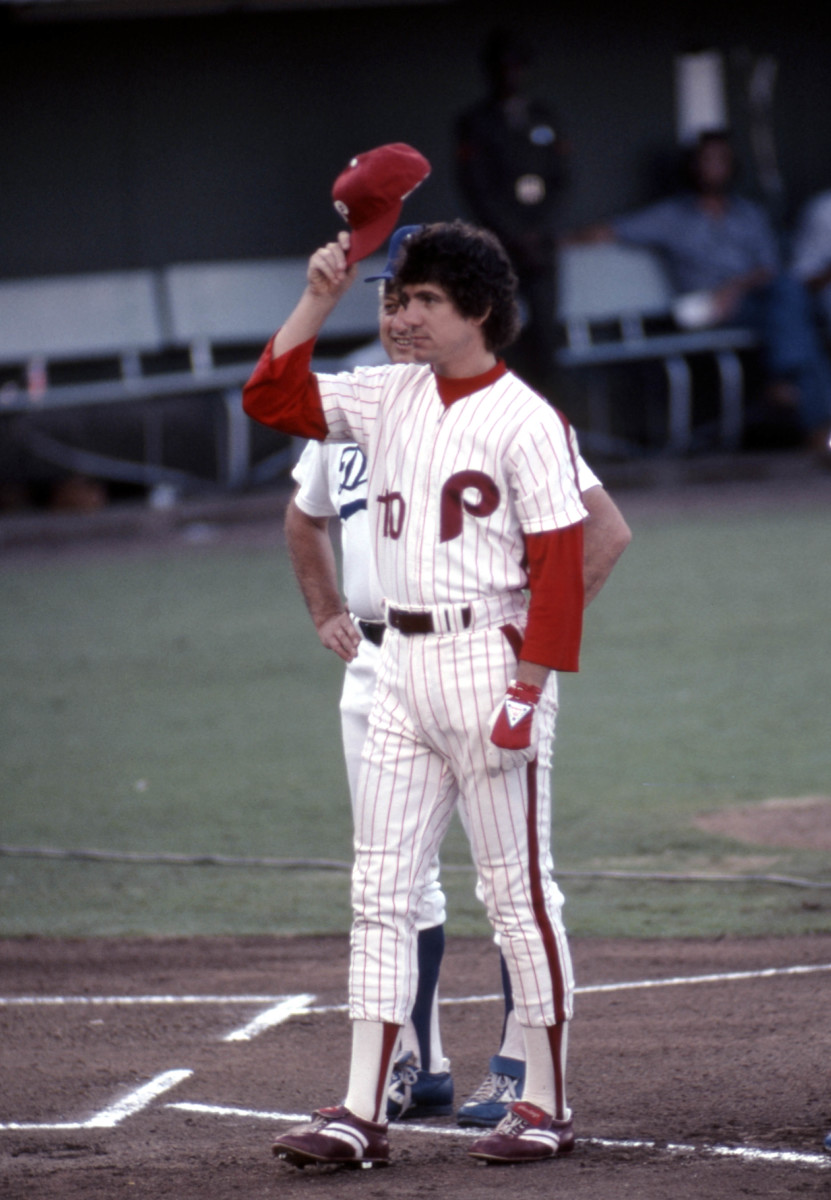

Larry Bowa (LB): My favorite story? It wasn’t a good one, believe me. It was in 1980, and we were playing the Chicago Cubs in a doubleheader. And the Cubs, at the time, were like bottom of the barrel. The first game, we were behind for 7 innings, and the boos started coming. Boo! Boo! Boo! Boo! We ended up winning in the ninth. The next game, we were behind, and we ended up winning. But the fans were definitely honest that we didn’t play the way we should have. And I told a writer that night that those were the worst fans I’ve ever seen; we won both games of a doubleheader, and we got booed. Of course, that wasn’t the headline. The headline was “Bowa says [Philadelphia] fans are the worst fans in baseball.” For the next three weeks, every time I put my head out of the dugout, I got booed. And I probably had my best month [of my playing career].

CM: Right now, like with the Eagles, just drive by there. You can feel it in the air. That’s all anyone will talk about. Of course, if they don’t win, the fans will be disappointed. But they’re still gonna show up, and they’re gonna scream.

LB: Another one I saw involved Mike Schmidt. The fans really started appreciating Mike toward the end of his career. I mean, he’s the greatest third baseman to ever play. And he started to finally make light of things. He would go out to first base with a wig on in pre-game. But before that? Man, they were tough on Mike. They really started to appreciate what Mike was all about because he was himself. His personality was low-key, but he was such a great athlete; he could do anything. But the fans, they came around.

The Indoctrination…

Ruben Amaro Jr. (RA): My [Philadelphia sports fandom] started with the Phillies, since my dad was associated with them and in the front office as a farm director and coordinated Latin American scouting and coached as well. I was a batboy for the team. My [Philadelphia sports memory] was the championships that our Flyers had. Those were the years of Broad Street Bullies. And one of my cool memories was putting my uniform on and being in that crowd in Northeast Philadelphia and celebrating with the rest of the fans.

CM: You go through a process when you first get there. I mean, they try you, and they're tough. When I first got there, it got to the point where the media was really getting on me. But at the same time, I’d already been through a lot. Philadelphia was different. It was hard for them to really get to know who I was. In our press conference, I told them, they might not like me now but when we win they will. And I kind of meant that.

LB: Without a doubt, they’re passionate. It’s a blue-collar city that wants effort. If you don’t give them effort, they’re gonna let you know. If you do, they’re behind you. You find out quickly, they’re very, very knowledgeable. They know what’s going on, doesn’t matter what sport it is. Whoever’s coming into Philly, good luck. The home-field advantage is real.

CM: When I first got there, one of my players used to tell me all the time, This is a hard place to play; boy, you gotta be real tough to play here. I didn’t think too much about that. I thought, What the hell, this is professional baseball! But after a couple months, I changed my mind.

LB: Take Ben Simmons. He’s a really good basketball player. But, yeah, effort. When he got on the wrong side of the crowd, man, they never forgot it. Didn’t matter what he did.

The Embrace…

CM: One year we went to Colorado, and we got swept in three games. That was the most disappointing period I ever had in Philadelphia, because our players were so down at the end of those games. You could hear a pin drop in the locker room. Then we show up [the next year] in spring training. The first day, I usually show up and give a big speech. But on that day, I didn’t have to talk long. Because the atmosphere in the room, they knew. They knew what the fans expected. We took off and ended up winning the World Series that year.

LB: I’d rather play under expectations that are high as opposed to low.

The Payoff…

LB: With everything I felt about, I knew: If you have a good pitcher, it doesn't matter where you're playing. But in Philadelphia, there’s a definite home-field advantage, and I really don't see it anywhere else. I've been to every other park. But it's when you get to that part of the season where every game is important. You can feel the energy, as soon as you walk into place.

RA: There’s no question about the passion. It really is one fanbase that I believe can actually affect the game. They can affect the outcome. I've felt that for years. And I think back, to the late 70s, when the Dodgers were playing in Philadelphia in the playoffs, and Burt Hooton was on the mound. And, I mean, they basically scared Burt Hooton into not being able to throw a strike. It was crazy. I mean, they were booing him for, like, a full inning.

LB: I think he walked three or four guys in a row. He could not throw the ball over the plate.

RA: I think there's an exaggeration as far as the nastiness that is portrayed. I've been around other teams. In San Francisco in particular, where I have been, and in Chicago; I love the fanbases there. But they’re every bit as nasty and filthy and derogatory—and I would say un-classy—as any other place.

CM: Momentum like the Eagles’ momentum goes everywhere. It’s on radio talk shows. It’s on television. It’s at restaurants when you go to dinner. It’s a different animal, the fan in Philadelphia, and if you’re playing here, it’s great to be on that side. No question.

The Winning…

LB: It’s believable. It’s the greatest feeling that I’ve ever had in a baseball uniform. First-ever World Series, the parade down Broad Street. I mean, you walk in, even though I haven’t played in a long time, but I’m still affiliated with the Phillies, I go into a restaurant and people come up and say, Oh, thank you. I say, Man, that was a long time ago. But they don’t forget. If you play the game, whether it’s football, basketball, baseball, or hockey, and you play with the edge or passion, they sense that, they can feel that. I’m not gonna say you’re never gonna get booed if you give 100%. They react to things. You can’t take it personally. I really believe that it takes a special athlete to play here. You have to have mental toughness, no doubt in my mind. And if you don’t, then they’ll run you out of town. And they can sense it, too.

RA: It has a lot to do with the fact they haven't won a ton of championships, either. They feel like they’re a championship city. Championships. There’s always an expectation to win there. And, you know, I abided by that. I mean, I adopted that thought process as GM. So there’s an added pressure to win in Philadelphia, but I wouldn’t want it any other way. Think about the head coaches who have been successful. Doug Pederson is beloved here. Charlie Manuel is beloved here. These teams kind of walk on water. They never have to buy another meal or another beer again. The perfect example is Andy Reid. He’s one of the greatest football coaches in the history of the sport. He’s a Hall of Famer. But at the same time, he never won here, and because he didn’t, he’s viewed differently.

CM: It’s real. The whole thing was very real. And there was no jealousy, there was no whatever; it was just a great time. Really, I mean, people kind of made it that way. I mean, the fans made it that way. Because they accepted our team and fell in love with the characters on our team and also how we played the game. The Eagles are the same way. Once they started winning, the city fell in love.

The Parallels…

CM: Jalen Hurts won them over. I watched Jalen in college when he was at Alabama. He never checked off his primary receiver. And I questioned how good he would be as a professional quarterback. In the last two years, he has really improved, really stepped up. He’s a great player. He’s had a great season.

RA: Fans identify with him for a variety of reasons. Jalen Hurts gets it. The thought process in Philadelphia is: It’s not about me, it’s about the team. He’s always putting the team first. His goals are not about accolades and accomplishments. He cares about winning a Super Bowl championship. He makes that clear pretty much every single day.

LB: When you take the field in Philadelphia, you better be ready to play. He is.

THEN TO NOW:

This is not relevant to the game. But I did love this anecdote before Super Bowl LV from Tammy Reid, detailing to my former colleague Jenny Vrentas what her husband’s “home office” looked like during COVID-19. Even the head coach of a team on the cusp of a dynasty had to do the same pandemic stuff as everybody else.

“This is really weird, because in Philly, we had this beautiful office, and we set it all up. And he said, 'I want to have it ready in case I ever have to watch film or come home and do stuff,' and I’m like ‘O.K.’ But this house did not even have anything that could be an office, really. So we just—he went to the basement, we smushed all the furniture to the wall, it probably looked crazy down there, and he just set up on one of my mom's antique tables that I had and brought his office chair here. And the guys set up all the stuff around him.”

ON BACKGROUND:

In speaking with team and league sources about Jalen Hurts and a contract extension with the Eagles, there are zero signs that the plan is anything other than to move forward with it. That makes total sense, of course. MVP-caliber season. Franchise quarterback. Expensive position, regardless. It will be interesting to see if the Eagles can do what the Chiefs did, which is extend Patrick Mahomes with a staggering deal that will look more and more like a bargain over time.

QUOTE WITHOUT CONTEXT:

“Mike and I talk about him all the time, because he's like our little bro. We love to see him flourish, and we just had conversations about him the other day. It’s not like he’s not making plays during the regular season. But the reason why teams will keep Frank around is because he makes plays in meaningful moments, in the playoffs, and it gets no more meaningful than that. He finds a way to get to the quarterback right then. Frank finds a way to make plays, and, as pass rushers, we respect those guys more. And that’s what Frank has learned and has done.”

CONTEXT:

This is Cliff Avril, longtime NFL defensive end, speaking about his former teammate Frank Clark, and conversations with their former Seahawks teammate, Michael Bennett. Clark ranks third all-time in postseason sacks. Don’t think those who mentored him haven’t noticed.

ELSEWHERE ON THE MMQB:

• From The MMQB Staff, a Super Bowl LVII Roundtable

• Mitch Goldich on whether current Eagles players remember Andy Reid’s tenure there

• From The MMQB Vault: Conor Orr on the Super Bowl Squares Kidnapping