The Sweet Life of Star Jets Corner Sauce Gardner

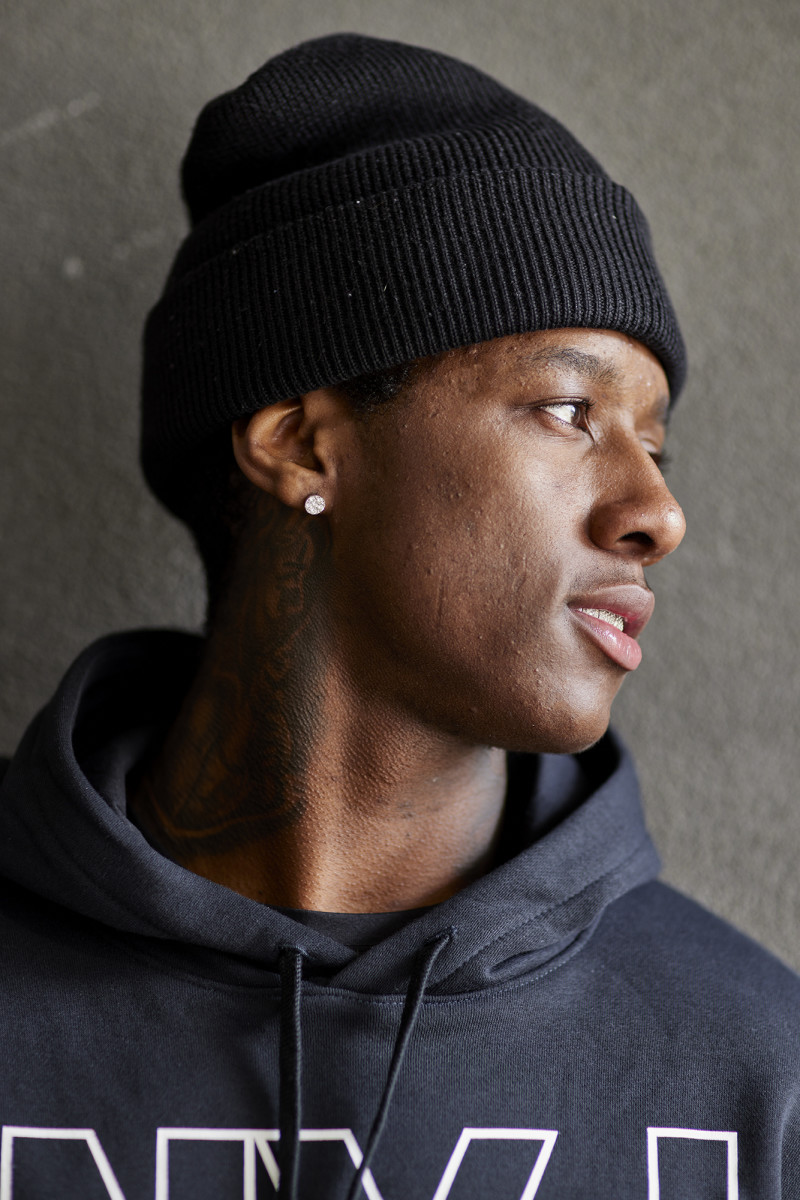

There are quiet moments, like midnight waves, when it seems like Sauce Gardner recedes and Ahmad Gardner comes to the forefront.

Take the day last year, during a starlit season that ended with a Defensive Rookie of the Year award, when Gardner found himself outside a row of designer stores in downtown Manhattan with a brick of cash in his pocket. Gardner doesn’t like to use credit cards, so wherever he goes he always arrives with a predetermined amount of spending money.

He locked eyes with an unhoused person on the street and, though the man didn’t ask him for anything, Ahmad palmed $1,000 with his goalie-glove-sized hand and gave it away. The man cried. Gardner, who went home without buying anything, says it was the third time he did something like that, in the third state, in a year. His former coach at Cincinnati remembers hearing about Gardner, during his junior season, leaning out of his car and handing an unhoused man $500 because they used to talk when Gardner passed him near campus.

Gardner says he is deep in thought during these moments, about his purpose and why God would have led him here, on this particular day, on this particular street, with a stack of hundreds resting in his coat. “Sometimes I’m just fighting battles with myself, like, you don’t need to do this for this person,” he says. “It’s harder [to say no to] people I don’t know. Autographs, for instance. They have to pull me [away] because I just keep signing. I keep seeing [fans’] expressions. I don’t ever want it to stop.”

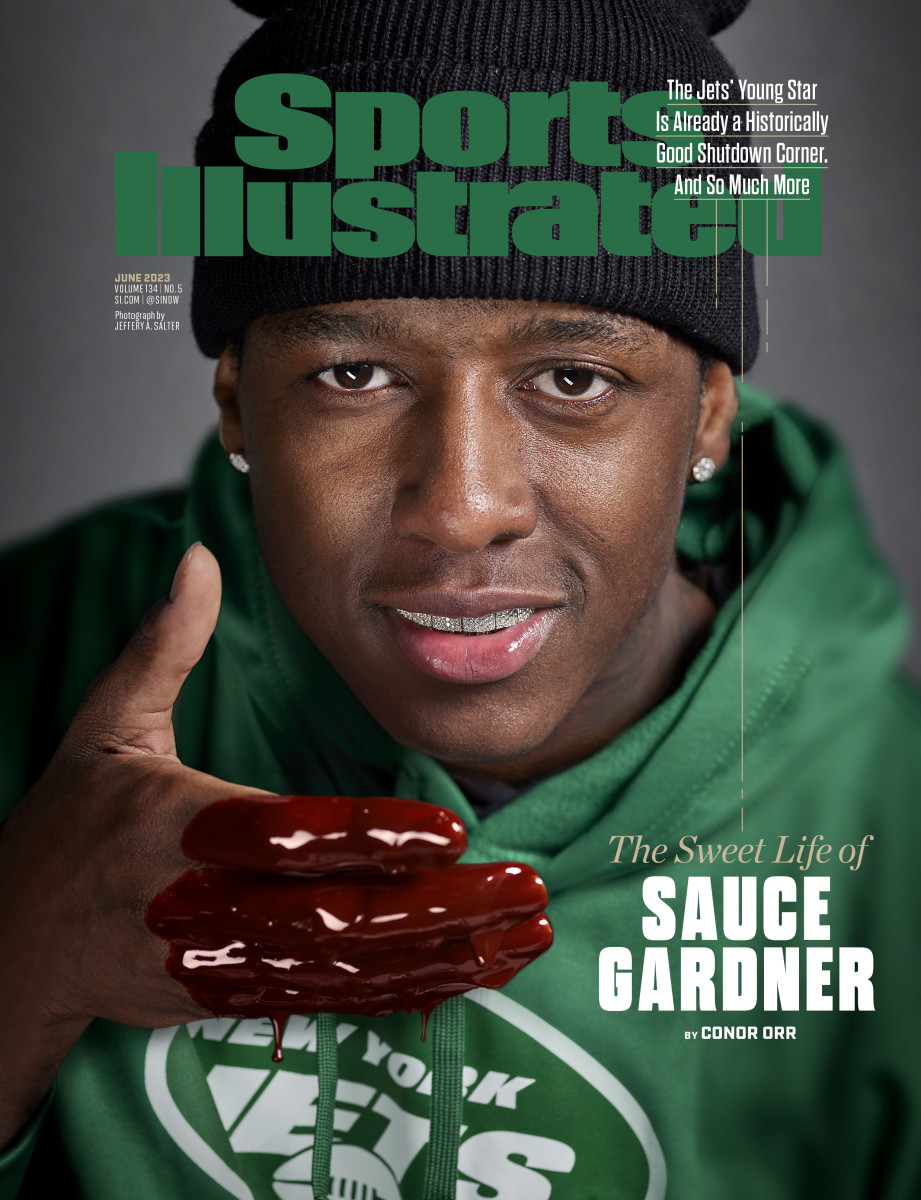

Gardner prefers to go by Sauce, the nickname a peewee football coach gave him when he was 6. Today, Sauce wears diamond grills in his teeth, helps deliver Aaron Rodgers to New York and burns Packers cheeseheads on his YouTube channel.

There is already a documentary in production about his life. “That’s what it is on the field,” he says of his nickname.

Ahmad is a counterweight to that flash. He’s a caring soul who provides a critical depth to the shutdown, showboat cornerback. He brings substance to his more marketable and definitive sobriquet.

Gardner talks about his generosity not to burnish his image but to illustrate the part of him that cares, or maybe to demonstrate the differences and connections between Sauce and Ahmad. He has the word EMPATH tattooed on his right forearm, which he reveals while overlooking Cincinnati’s football field on a rainy April Sunday by lifting the sleeve of his black jacket. It is a symbol of how he feels: the joy of being famous and the burden of never wanting to leave anyone behind. Gardner will often read and respond to his direct messages on social media, shocking fans who preface their reach-outs with I’m sure you’re not going to read this, but . . . He’s only 22, but he already runs a virtual business venture aimed at steering people out of gang life. He talks to high school football players constantly because he wishes someone had shown him a way out when he was that age.

Gardner had to find that blueprint for himself. Before he was known universally as Sauce, before he was a catalyst for the Jets’ Super Bowl dreams (“I definitely think this is the year for it,” he says), before he was helping assemble a superteam, he was a 14-year-old in Detroit watching a man get shot to death in front of a liquor store. Ahmad was just walking out of the barbershop one day; for years he didn’t tell a soul about what he saw, despite the dark thoughts that would intrude on his mind when he heard the metallic popping sounds on Call of Duty. He was afraid his mom would coddle him if she knew he was struggling.

It was in those moments that his personality was solidified. Ahmad decided he would never touch alcohol or cannabis, believing them to be contributing factors to the kind of spiral that could get someone stuck in a neighborhood, on a corner, in a life they couldn’t escape. He would read the Bible, as he still does regularly, flipping open to random passages in Philippians or Psalms to try to ascertain the meaning (a process, he says, that has gotten easier with time). He would, as his mom challenged him, do only what would make him different from the people who wouldn’t make it out. He would devote his life to never letting down anyone who wanted the same for themselves.

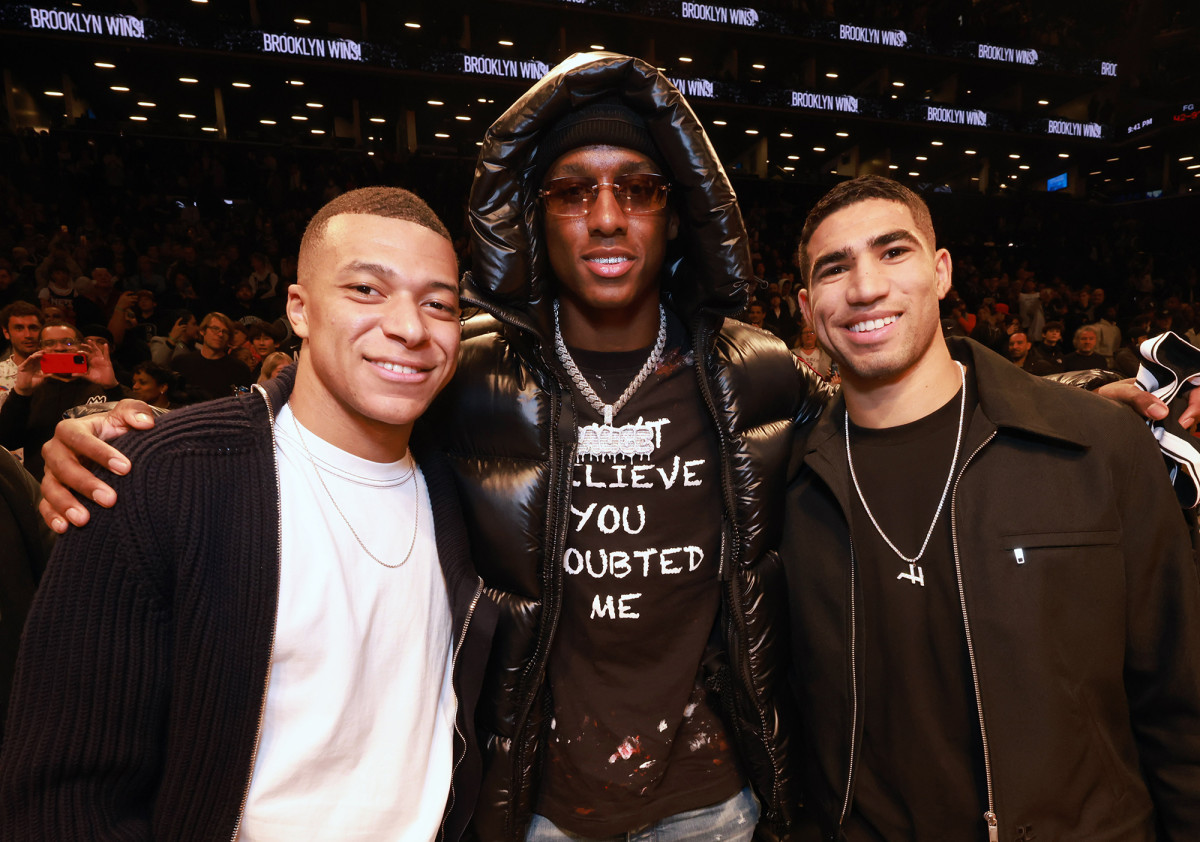

When viewed together, Ahmad and Sauce are a force of goodwill. For two football programs, Gardner has been a talisman for the kind of change coaches can only dream of. At Cincinnati, the Bearcats are walking into the transfer portal like Ric Flair, telling recruits they’re with the Sauce. In New York, the Jets are flagging down stars like a casting director for Quentin Tarantino, with Gardner and a group of young phenoms as their main selling points.

It’s all part of the plan, to please everyone. To give away the kind of life he had to earn. Ahmad and Sauce can’t see another option.

“I have to carry myself a certain way,” he says.

Gardner walks toward the field at Cincinnati’s Nippert Stadium, down a set of stairs. A driving, sideways rain has faded, and the sun is wrestling its way through the blankets of gray sky. He picks up a point he started making a few minutes earlier, about “just seeing people want to play for the Jets.”

After a rookie season that was one of the best debuts for a cornerback in NFL history—a first-team All-Pro nod; two interceptions; a league-best 20 passes defended; just one touchdown allowed; an opposing quarterback completion percentage of 44.7% when targeted, among the best in the last decade—Gardner spent this offseason recruiting more help. One of his primary targets was Odell Beckham Jr., the iconoclast wide receiver who has struggled with injuries over the past three seasons. Still, Beckham is one of the most famous players in the NFL. Sauce has him on speed dial. While Beckham eventually signed with the Ravens for a one-year contract worth up to $18 million, Gardner insists the Jets were in the conversation for his services.

“Odell, he wanted to play here,” Gardner says. “It was to the point where he was picking his jersey. He was telling me, like, ‘Hey, ask so-and-so if I can get the jersey [number I want].’ He was going to wear number 7.”

He added: “I’m texting guys like Aaron Rodgers. Feel me? I never thought I’d be texting guys like that.”

Gardner reached out to Rodgers a few months after the Jets demolished the Packers at Lambeau Field during Week 6 of the 2022 season, one of the defining victories of the Robert Saleh era and proof that the franchise had found its footing after years of irrelevance. The turnaround began with last year’s draft: Along with Gardner, whom the team took with the fourth pick, the Jets had procured wideout Garrett Wilson, who would be the NFL Offensive Rookie of the Year, with the 10th. Running back Breece Hall, a second-round pick, was on pace to contend for the NFL rushing title before tearing his ACL in Week 7. The Jets now have one of the best defensive linemen (All-Pro Quinnen Williams), wide receivers (Wilson) and cornerbacks (Gardner) in the league and appear more talented, as a roster, than they have at any point in the past decade.

After breaking up three passes in the 27–10 win in Green Bay, Gardner celebrated by climbing into the stands and grabbing a cheesehead, the ultimate symbol of Packers fandom, and placing it atop his head. He walked around, arms spread like a Mortal Kombat character after the finisher. He jogged into the tunnel still wearing it, before then Packers receiver Allen Lazard chased Sauce down and flipped it off his head with a small twap. (Lazard would end up being one of the Jets’ free-agency signings this past offseason as part of the effort to lure Rodgers.)

“‘What do y’all think you need [to be competitive]?’” Gardner says Rodgers (who before the trade was stored in Gardner’s phone as arod, with a fingers-crossed emoji next to it) asked him during their message exchange this offseason. “First thing I did, I texted him a picture of the cheesehead. And he said, ‘LOL why do you still have that?’ I told him, ‘Hey, you become a Jet, I’ll burn it. You don’t have to worry about it.’ ” Gardner later melted it on his YouTube channel, in a backyard firepit behind his house, with teammates Wilson and Hall watching.

By mid-March, Rodgers had declared his intent to play for the Jets. In late April, three days before the draft, the trade was finally completed. Two years ago, the thought of a Hall of Fame quarterback near his prime playing for the Jets would have been a hallucination, the fan-fiction equivalent of a grocery store paperback. Gardner helped make it come to life. To celebrate, he changed his Twitter avatar to a picture of Rodgers in college.

Gardner recognizes parallels between his experience now and what happened during his time in college. Back in 2019, in front of a packed-house night crowd against No. 18 UCF at Nippert, he entered the game late as a freshman substitute and picked off a ball that he returned 16 yards for a pick-six. It was one of two touchdowns and nine interceptions he logged over 33 college games. He did not allow a single touchdown. He led the Bearcats to an appearance in the 2021 College Football Playoff; the first time a non–Power 5 school had appeared in the postseason. He became the highest-drafted player in school history.

Now, the school’s athletic department has rebuilt itself around his legacy. Recruits are shown a Sauce mannequin on the fourth floor of their football complex, and a Sauce highlight compendium plays on a screen in the lobby, including footage of him walking across the stage on draft night in a powder-blue suit and a sauce diamond chain with more glitter than a day-care art project.

“Our 2024 recruiting class is named after him,” says Zach Stipe, the school’s associate athletic director for communications and strategic brand engagement. “He’s that perfect culmination of all factors: success on the field and personality.”

The 2024 Bearcats recruiting class, by the way, is called “2 Much Sauce.”

On some nights, Gardner appears live in New Sauce City, a role-playing server he oversaw the development of within the Grand Theft Auto 5 platform. The world functions just like a real-life city. There are suburbs and arms dealers; a police force and restaurants. The point is to allow anyone to do anything. As Gardner plays, hundreds of comments pour in from his subscribers and viewers. Some people ask about the braces he had in college (“I always wanted braces,” he says).

Some people ask him who is playing quarterback for the Jets next year.

On this particular evening, Gardner is stopping by a virtual jail to counsel someone who may have taken a shot at a virtual police officer. Gardner’s actual voice plays through his digital character, a muscular, broad-shouldered avatar that he carefully dresses multiple times in each playing—at this moment Virtual Sauce is wearing jeans and no shirt. The voice of the person in jail is real, too. He has paid $25 to join New Sauce City.

“Word on the street was that you popped one of the officers,” Sauce says to the man. “But you want to know what I told them? ‘He’s young. He is going through a lot of stuff.’ I’m going to talk to the officer, see what kind of bond I can get. I’m trying to pull some strings. Me and the officer got some history. I need you to cooperate. I can’t have you doing stuff like this.”

Gardner called the creation of this server a “genius” move, but not necessarily because of the money he’s making—after that early $25 fee, some in-game purchases go for more than $200. (He says his daily queue of available players is always full, with multiple people waiting to get in.) “It’s like an open world,” he says of the game. “You can choose to start your own story line. You can come in and you can be like, ‘I want to be security. I want to be a police officer.’ Cool. If you want to be a gang member or something like that . . .”

Gardner wants a place for people affiliated with gangs or attracted to the lifestyle to live out their fantasies online “so they’re not doing it in real life. It’s a lot of people who are in the streets, but it’s a lot of people who are in the streets and got money and have access [to a computer],” he says. “So my job of doing it was to get them out of the streets and let them live whatever lifestyle they wanted to live in the streets in my game, if that’s what they choose to do.”

It’s not hard to recognize the person he’s trying to be in real life inside the person he’s trying to be virtually. Some people turn to video games to release anger or live out fantasies through a Madden franchise. Gardner is funding the virtual down payment on people’s virtual cars or trying to get them out of prison (while having a blast playing Grand Theft Auto as designed).

One has to wonder whether it’s a way Gardner can square his thoughts and experiences in Seven Mile and East Warren, the Detroit neighborhoods where he grew up. He talks about the strange juxtaposition of seeing someone walking their dog and then seeing someone get killed. He wanted something better. Over an hourlong conversation, he mentions more than a half dozen times the need to set a good example in case someone else is watching and trying to escape, someone like the boy he used to be. He says there’s a need to constantly reevaluate himself so that he can remain the human equivalent of a lighthouse for wayward souls.

“I always just have to make sure I’m doing everything right. You know what I mean?” he says. “I’m just staying focused, staying humble because I know if I were to mess up in any kind of way that can affect a lot of people. You know a lot of people that’s trying to get to where I’m at today, my family. So that’s why I’ve always been one of those guys.”

He’s not trying to set a good example: “I’m trying to be the perfect example.”

Hence, video games as a vice and, in some sense, a solution. In lieu of smoking or drinking, Gardner likes to congregate here with his audience. Almost 10 years after the most horrifying moment of his life, he’s still chiseling out the person he wanted to be.

“I’m like, Shoot, it could have been me. It could have been somebody I knew. I knew that,” he says. “I mean, it made me want to go harder.”

When Gardner was 6 years old, his football coach started calling him “A1 Sauce Sweet Feet Gardner” or “A1” for short. Over time, the nickname was whittled down. It became a part of him.

When he got to Cincinnati, then coach Luke Fickell refused to call him that. Fickell said, half-jokingly, that he’d call the defensive back Ahmad until the day Gardner was drafted. When reporters asked him about “Sauce,” Fickell would respond, “I’ll talk about Ahmad.”

“You had this confident, young freshman coming in, and I always tease guys, ‘Oh, you have a self-proclaimed nickname?’” Fickell, now the coach at Wisconsin, says, laughing. “He was like, ‘I’m Sauce.’ And I said no, your grandmother calls you Ahmad. I’ll call you Ahmad.” (Gardner invited Fickell to the 2022 draft and hugged his coach before he went on stage. Fickell looked him in the eye and said, “Congratulations, Sauce.”)

The Jets adopted a similar stance last year in training camp, forcing the rookie to earn the nickname that had already brought him significant NIL deals (including a signature barbecue sauce at Buffalo Wild Wings) and, perhaps, the most recognizable profile for a young defensive back since “Prime Time.” Gardner says defensive coordinator Jeff Ulbrich, who played 10 NFL seasons, would loudly correct himself in Gardner’s presence, strategically letting a Sauce slip before recovering with an “Uh, I mean, Ahmad.”

That changed following the Jets’ season opener against the Ravens. Gardner was given the most difficult defensive assignment: Shadow tight end Mark Andrews on third downs. Andrews, who is at least 40 pounds heavier than Gardner, is a bullish focal point of Baltimore’s passing game and one of the most targeted pass catchers in football. It didn’t take long for Gardner to establish his NFL profile. Late in the first half, Lamar Jackson lofted a 40-yard fade route to Andrews, leading him toward the end zone. Gardner kept his eyes affixed to Andrews’s with his back completely turned to the quarterback, then knocked the ball away as the tight end began to pivot back toward Jackson. Their bodies slammed the turf together as the ball tumbled incomplete.

Gardner held Andrews to one reception on the plays where they were matched up. The following Monday, the way Gardner remembers it, Ulbrich told several defensive players watching the film that the breakup was a “nice play by … SAWWWWCE,” emphasizing the nickname and crowning him the player the Jets already knew he was privately. “Everybody got to turn up,” Gardner says. “You know it was good vibe.”

The following week, he marked Amari Cooper, one of the best technical route runners in the league. Then Ja’Marr Chase. Justin Jefferson. Stefon Diggs. Tyreek Hill. One film analyst who compiled all of Gardner’s snaps in man coverage noted that, against nearly all of the best wide receivers in the NFL, Gardner had surrendered four catches for fewer than 30 yards when it was just him against those elite wideouts. Asked now whether there is any receiver out there who gives him pause, Gardner quickly responds: “No.”

He adds: “I think I can handle everybody until it’s proven differently.”

Of course, he has to say that—Sauce knows what the Jets need of him. He may have had to earn his nickname against a rhinoceros-sized tight end, but the truth is that Gardner spoke his mind on Day 1 of his first NFL training camp and no one on the team told him to quiet down. They could see it. They could hear it. “Anytime I talked,” he says, “people were listening.”

Such is life when someone’s inner worlds are in harmony. Ahmad takes care of Sauce, and Sauce—he signed with the Jets for $33.5 million over four years—gives Ahmad the life he dreamed of back in Detroit, back when a free ticket to a Pistons game and a safe trip home represented the lap of luxury.

They have shared goals and visions. A league MVP award. A Super Bowl. Business enterprises. Happy fans and customers. Gardner understands the burden of the empath. But he shows no signs of pushing it away.

As Gardner walks out of the Bearcats’ facility, a member of the football staff tells him they’d just nabbed two more recruits for the “2 Much Sauce” class. He signals his approval. He steps into the stadium he packed and lit up like a Molotov every Saturday. Over there, on the 15? That’s where he picked off that pass against UCF. That’s where he ran, into the opposite corner of the end zone, after he scored to face a delirious crowd that would later storm the field. That’s where people started to understand the true meaning of Sauce.

In a few hours, his plane would leave for New Jersey. Another day in the life of Sauce and Ahmad, two sides of a man who believes he cannot be stopped.

Fickell, who still keeps in touch, ends every text to Gardner the same way: “Don’t ever change.”