Jim Brown Lived a Remarkable Life Like Few Other Athletes

[Editor’s note: This story was written by Tim Layden during his 25-year career as a senior writer at SI. He is currently a writer-at-large for NBC Sports.]

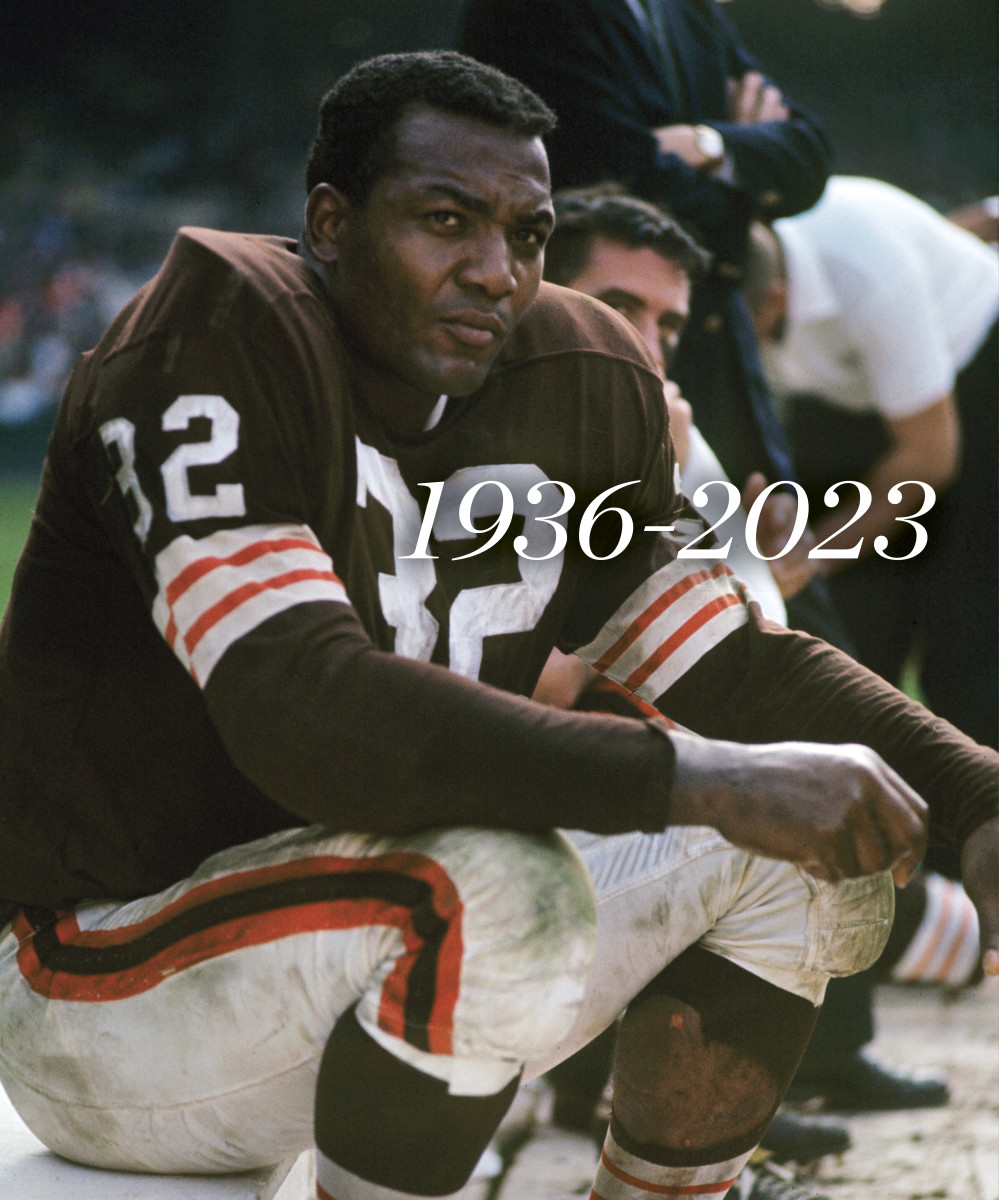

On the occasion of a man’s death, society rushes to succinctly define that man. Jim Brown, the legendary Browns running back, has died, according to multiple reports. Brown’s wife, Monique Brown, confirmed the news of the icon’s death on Instagram Friday afternoon, announcing he “passed peacefully” in their Los Angeles home Thursday night.

He was 87 years old.

It would be succinct to define Brown as the best football player in history. There is plenty of statistical and visual evidence to support this superlative: Brown rushed for 12,312 yards in nine seasons and remains the only player in NFL history to rush for an average of 100 yards per game; he endures on grainy videotape as a superhuman performer, a force of nature who alternately overpowered, outran and outthought an entire sport, generations ahead of his time. Respected minds line up to praise him, without challenge. “The greatest football player, ever,’’ Bill Belichick told Sports Illustrated in 2015. “No doubt.”

Brown would appreciate this acclaim, because his ego remained firmly in place, even in the last years of his life. But he would do something else, too. He would laugh, in a knowing chuckle that was at one time in Brown’s life the ominous introduction to a corrective storm that would follow; and much later, the weary admission that nobody can fully grasp the scope of his life, without getting caught up in football feats accomplished decades earlier. The laugh would sound like this: “Heh, heh, heh …” And then would come the deeper truths of a long life, by turns pioneering, generous, controversial, caring, violent and polarizing. A remarkable life broken into disparate parts, such as few other athletes have lived.

Jim Brown was not just the best football player ever to pull on pads and a helmet, he was also one of the most complex sports characters of the 20th century—on the field a transcendent ballcarrier, and off it a forceful social activist and a leader among the first generation of Black athletes to use their status as a weapon in the nascent civil rights movement. He walked away from football in 1966 at the age of 30—while still dominant—leaving not a period at the end of his football biography, but an ellipsis. By then, he had already begun building a formidable career outside of football. Brown helped start the Negro Industrial Economic Union (later renamed the Black Economic Union), which would provide financial assistance to more than 400 Black businesses. He launched a movie career in ’64 that would span five decades and 43 movies, and help expand the breadth of roles offered to Black actors. In the early ’90s, dispirited by gang violence in the inner cities, Brown founded the Amer-I-Can program, whose fundamental purpose was teaching life management skills to young Black men, both on the street and in prisons. Hundreds of gang members have visited his home in the Hollywood Hills, and in turn Brown has made hundreds of visits to prisons, his physical presence never dulled by age, often with a green, African kofi on his head. Brown’s conscience never lost its force; his voice never lost its impact.

Yet his relevance was irreparably damaged by a history of domestic violence that stretched across nearly his entire adult life and became even more pertinent to his legacy as society became more acutely intolerant of men—and especially athletes—who abuse women. The NFL star and activist faced numerous assault charges. In the first four cases the charges were either dropped or he was acquitted after female survivors decided not to testify against him. In 1999, Brown, who was 66 at the time, was arrested after Monique, then 25, called 911 from a neighbor’s house in Hollywood Hills to report that her husband had smashed the windows of her car after an argument with her.

The couple went public together and fought the charges in a series of media appearances. Jim was found guilty of vandalism, and, rather than accept any plea bargain, he served six months in prison. Late in life, Brown expressed a form of remorse at his behavior. “There is no excuse for violence,” Brown told Sports Illustrated in 2015. “There is never a justification for anyone to impose themselves on someone else. And it will always be incorrect when it comes to a man and a woman, regardless of what might have happened. You need to be man enough to take the blow. That is always the best way. Do not put your hands on a woman.” Whether these words would soften Brown’s legacy is left now to history.

Brown was married twice—to Sue Jones from 1958 until they were divorced in ’72—and to Monique (Gunthrop) from ’97 until his death. With four women he had eight children, including son Aris and daughter Morgan, whom he raised with Monique.

James Nathaniel Brown was born February 17, 1936, in St. Simons Island, Georgia, to Swinton “Sweet Sue” Brown, an amateur boxer and semiprofessional football player with a penchant for cards and dice, and his wife, Theresa Brown. Sue abandoned Brown not long after he was born, and not long after that, Theresa moved to New York in search of work. Jim was raised until age 8 by his grandmother, who was named Nora, but who Brown called Mama. In ’44, Brown’s mother called for him, and Jim moved to Manhasset, Long Island, where Theresa was working as a maid. Where St. Simons had been mostly Black, rural and unspoiled; Long Island was largely white, crowded and intense.

Brown was an athletic prodigy who would eventually star in multiple sports—football, basketball, lacrosse and baseball—at Manhasset High School, where he also was watched over and mentored by a group of white professional men in the community who demanded that he study and involve himself in student government. Chief among them, lawyer Ken Molloy, a graduate of Syracuse, insisted that Brown enroll there in the fall of 1953, turning aside numerous other colleges recruiting Brown. Molloy told Brown that Syracuse was giving him a scholarship when, in fact, Molloy had raised the money himself to pay for Brown’s freshman year. In his ’89 memoir, Out of Bounds, written with Steve Delsohn, Brown called Molloy, who died in 1999, “A man who lives his life for others, especially kids. … I love Kenneth. I’m proud to be his friend.”

In the fall of 1953, Brown was the only Black player on the Syracuse freshman team, lived in a separate dormitory from other players and was buried at fifth-string tailback on the depth chart. The Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education case was six months away. “I came up at the crossroads of segregation,” Brown told SI’s Steve Rushin in ’94. That sentence would be the foundation of Brown’s life. He nearly left Syracuse that freshman year but endured, and not only earned a scholarship, but also became a first-team All-America running back as a senior and led Syracuse to the Cotton Bowl in ’57. He was an All-American in lacrosse under coach Roy Simmons, who Brown called, “the only coach at Syracuse who was good to me from the day I arrived.”

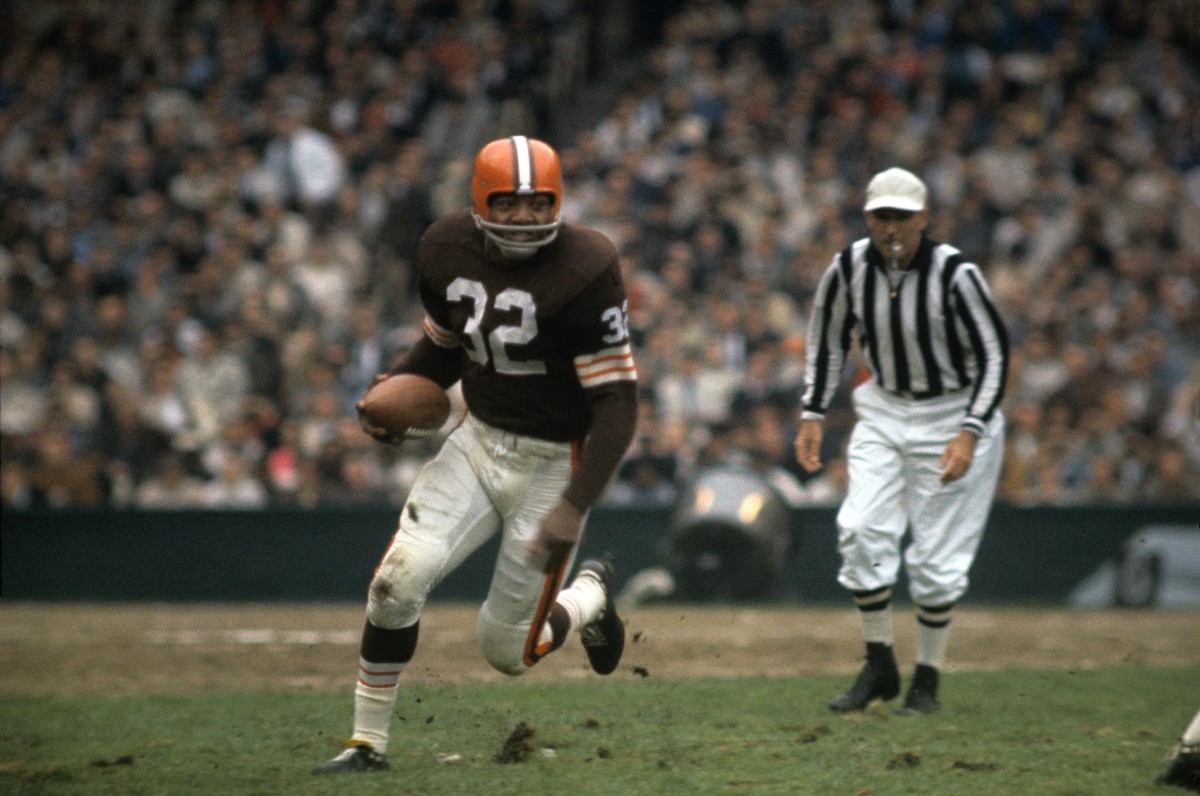

Brown was drafted sixth in 1957 and tore through a career remembered equally for its dominance and brevity. In Brown’s second season, he rushed for an NFL record 1,527 yards and an average of 5.9 yards per carry. He was powerful in the extreme, shedding tacklers like a combine down a wheat field. Giants All-Pro linebacker Sam Huff said, famously, “All you can do is grab hold, hang on and wait for help.” But he was also stunningly nimble for a large man. “He was a combination of a fullback and a halfback,” Belichick said. “He had great power and leverage, but he was also very elusive in the open field like a halfback. His quickness, straight-out speed and elusiveness were all exceptional. And he was all of 230 pounds. He was bigger than some of the guys blocking for him. I mean, they might have weighed more, pumped up, but Jim’s hands, his forearms, his girth, he was bigger.”

But Brown used his mind as efficiently as his body. “I studied the game,” he said. “I studied my opponents.” Ernie Green, who played with Brown in the Cleveland backfield, said, “I was never in the presence of anybody who prepared the way Jim Brown did.” Years later, when Belichick was the coach in Cleveland from 1991 to ’95, he marveled at the way Brown would explain to young running backs the ways in which to set up a tackler to miss. In the locker room, Brown was a commanding presence but often distant from many of his teammates. “Jim liked to be in control,” Frank Ryan, the Browns’ quarterback from ’62 to ’68, told SI in 2015. “But he was a tremendous football player. He was impressive in every possible way, just a superb athlete. We never really warmed up to each other, but I never lost my admiration for him.”

After the 1962 season, Brown’s sixth, he was among a group of players who supported owner Art Modell’s firing of legendary coach Paul Brown, a pioneering genius who Brown—and others—felt had been left behind by the game’s advances. The next season, under coach Blanton Collier, Brown rushed for an NFL record 1,863 yards (breaking his own record by 356 yards, with the season expanded from 12 to 14 games). The Browns won the NFL title in ’64. In ’65, Brown led the NFL with 1,544 rushing yards, 677 more than rookie Gale Sayers of the Bears, and at 29, was named league MVP for the third time. He never played another game.

In 1964, Brown had begun an acting career, appearing in a western called Rio Conchos. In the 1965 offseason, he was working in a World War II movie called The Dirty Dozen. Production delays caused filming to drag past the start of Brown’s training. Modell threatened to fine Brown for every day of practice missed. On July 14, sitting in front of tank replicas on the movie set in London, Brown announced his retirement. The next day, he told SI’s Tex Maule: “I could have played longer. I wanted to play this year, but it was impossible. We’re running behind schedule shooting here, for one thing. I want more mental stimulation than I would have playing football. I want to have a hand in the struggle that is taking place in our country, and I have the opportunity to do that now. I might not a year from now.”

And later this: “I quit with regret but not sorrow.”

Half a century later, Brown reflected on the decision. In truth, it was only partly influenced by the movie delays. Brown was ready to leave, and Modell’s ultimatum pushed him over the edge. “You want the real story?” Brown asked an SI writer in 2015. “I had no bargaining power. But the only thing the Browns had over me was that if I wanted to keep playing football, I had to play for the Browns. But they couldn’t tell me I had to play football. Art was going to fine me for every day I stayed on the movie set? I said, ‘Art, what are you talking about? You can’t fine me if I don’t show up. S---, I’m gone now. You opened the door.’”

When asked about the ellipsis, the what if Jim Brown had played a few more years, Brown said, “My ego is such that I did what I did on the football field. If you like it, cool. If you don’t like it, that’s alright with me, because I can’t do it no more.”

Paul Wiggin, Brown’s teammate, said, in 2015, “Jim retired two years before I did. He could have played 10 years past me.” Brown retired as the NFL’s all-time leading rusher, a record that lasted until 1984, when Walter Payton went past him in 18 more games and 451 more carries. He remains the only player in NFL history to average more than 100 yards per game (104.3).

A new life started almost immediately. Brown moved to a home in the Hollywood Hills, where he would live the rest of his life, a modest house with a breathtaking view of the city below. Brown acted in 16 movies in nine years. His interracial love scenes with popular actor and sex symbol Raquel Welch in the 1969 movie 100 Rifles broke Hollywood. Brown was never considered a talented actor, but his roles stretched boundaries previously placed on Black actors.

In the volatile 1960s, Brown embraced the role of a civil rights warrior that would define much of his adult life. It was a role that he relished, even before he left football. In ’64 he wrote Off My Chest with sportswriter Myron Cope. The book was part memoir, part manifesto. On page 163, Brown wrote, “I crave only the rights I’m entitled to as a human being. The acceptance of the Negro in sports is really an insignificant development that warms the heart of the Negro less than it does that of the white man. … The problem is a little bigger than a ball game.” When Muhammad Ali refused induction into the U.S. Army in ’65, Brown was among the athletes who organized a civil rights summit in Cleveland. At a historic press conference, Brown sat next to Ali, flanked by Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Brown became a strident voice on race in America, a powerful presence that often made white audiences uncomfortable, which is exactly how Brown would have it.

Brown threw himself into the work. More than 400 businesses were aided by the Black Economic Union, which also helped fund college educations for Black high school students. When gang violence infected America’s inner cities, Brown set out to help its victims. Amer-I-Can employed—as Rushin wrote in 1994—”street-credentialed facilitators,” who would help teach basic life skills such as reading and managing personal finances. And Brown’s own bona fides were rarely questioned, but always proved. From Rushin’s ’94 story: “A visitor to one symposium on gangs in Brown’s home kept disrupting the host’s efforts to establish a dialogue. After Brown repeatedly asked the young man to excuse himself, the young man challenged Brown to step outside with him. Well, Brown and the young gang-banger wound up rolling out the back door in a comic book cloud of dust. Shortly thereafter, they reappeared and shook hands, and the meeting resumed.”

There’s little doubt that Brown saved lives. But for many years, he never dropped his personal wall of indignation or controlled his temper. It would flare during interviews, such as a 1994 encounter with a GQ reporter, in which, as reported by Mike Freeman in his 2006 book, Jim Brown: A Hero’s Life, during which Brown shouted at the writer, who had begun asking sensitive questions, “No interview! I don’t need no magazine story, big guy. Y’all came to me. I’m not like these sorry-ass mother-----rs, sitting around remembering their fame, these old Black athletes. … I’m living my life. I’m doing my work. Sheeee-it.’’

That temper did its worst damage in Brown’s treatment of women. The first publicized incident came in 1965, when Brown was found not guilty of assault against Brenda Ayres, then 18, after an incident in Brown’s hotel room. Three years later Brown was charged with assault with intent to commit murder when model Eva Bohn-Chin was found beneath the balcony of a second-floor apartment. Brown told police that Bohn-Chin jumped off the balcony, and charges were later dropped when Bohn-Chin refused to name Brown as the assailant. Thirty-four years later, filmmaker Spike Lee interviewed Bohn-Chin for his documentary, Jim Brown: All-American. When asked whether she had jumped off the balcony, Bohn-Chin said, emotionally, “Why would I jump?”

It was 17 years to the next documented incident, when Brown was described as having raped a 33-year-old guest in his home. The judge threw the case out, citing inconsistent testimony; a year later, in 1986, Brown was arrested and charged with assaulting his girlfriend, Debra Clark. Charges were dropped when Clark refused to prosecute. In ’99, Brown smashed Monique’s car windshield with a golf club, prompting a frantic 911 call by Monique and a massive police response that included 15 squad cars. Brown served six months on the vandalism charge. In 2015, Monique told SI, “We had an argument, and Jim damaged his own property. There has never been any domestic violence in our home. He has talked to our son. It is not something that Jim would ever tolerate.”

There were no more incidents at the time of Brown’s death. He would assure listeners he had changed over the years and understood his mistakes. In July 2015, he watched a video of his younger self on the football field and, when the show was finished, stood and nodded. “Thank you for showing that to me,” Brown said. “It’s funny. I keep seeing things I could have done better. Things I could have done differently. That’s the way it is with football.” He paused, and added, “That’s the way it is with life, too.”

Brown retained much of his stature deep into his life. Just before the opening tap of the third game of the 2015 NBA Finals, Lebron James of the Cavaliers spotted Brown sitting courtside and did a deep bow in respect. Brown nodded almost imperceptibly. You could almost hear the laugh. Heh … heh … heh.