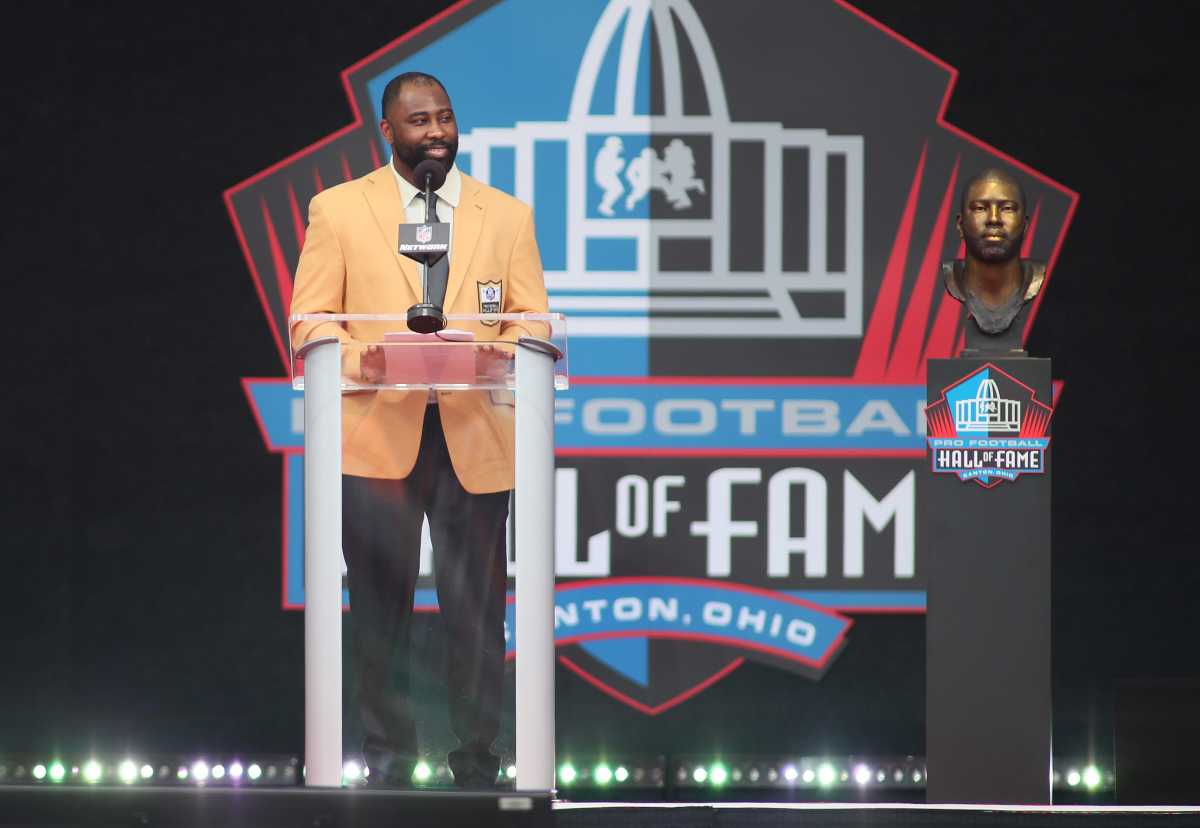

Twenty-Four Short Stories About New Hall of Famer Darrelle Revis

Twenty-four short stories about Darrelle Revis, matching his uniform number, in honor of induction this month into the Pro Football Hall of Fame:

1. Darrelle Revis has the best email address. It’s as elite as his playing career, those 11 (mostly) dominant seasons, played (mostly) in New York, for the Jets. His email address is perhaps the best such string of letters and numbers ever composed. Out of respect for his privacy, there’s no reason to publish it in full. But let’s just say three parts are my … own … island.

Revis is funny like that, for those of us who have gotten to know him. He never made that easy. But he is funny. Sneaky funny. The Quip—a nod to his hometown of Aliquippa, Penn.—with dry quips. Remarkably intelligent. Loyal. Driven. The kind of player who, in hindsight, was destined for Canton.

I’ve been doing this, writing about professional athletes but especially NFL stars, for some 21 years. And, while a certain distance is necessary to maintain and a flawed concept like unflinching objectivity must always be considered, certain players stick more than all the rest combined. Chronicling their careers, their brilliance, becomes a ride of sorts. For me, Revis was one of those, a player who wasn’t easy to gain access to but who opened his world once he granted an audience, an elite talent who didn’t mind explaining his process, what made him so. It’s hard to pin an exact number, but I think I interviewed him in at least 15 states, after bad games and perfect games, boring snoozers, taut defeats and triumphant victories. We spoke inside casinos, hotel rooms, restaurants, lounges, cars, locker rooms, apartments, houses and mansions; on football fields, poolside, at Super Bowl parties, on beaches, at craps tables, bars, outside of facilities and restaurants and on the High Line in New York City; on the phone; about money and business, family and loyalty, Rex Ryan and Bill Belichick.

Each interaction formed a story of its own, as a young sportswriter grew old and came to identify with many Jets fans of similar middle age. I can trace my adult life through Revis, our interactions and his career. After weeks of celebrating his greatness, which was, frankly, a joy to observe up close, perhaps our time together is instructive. If not, the 24 stories/anecdotes/observations here are at least sometimes funny, sometimes revealing, sometimes without precedent, sometimes strange and, overall, distinct.

2. Revis once tried to buy me a suit. After years of being treated (mostly) like an unwanted pest tagging along for the briefest of possible interactions, this typified Revis, the human being, who wasn’t as uncaring as many often painted him. If he knew you, respected you or counted you among his confidants—I’d qualify for the first two but not the third—he was as loyal as they come. We were in Manhattan that day and had just taken a strange, slow and surreal walk through Times Square, where Revis posed with Minnie Mouse, and she chased us down the block for a tip afterward. A cornerback known for contracts, holdouts and changing financial paradigms didn’t have any cash. But his tailor, at the next stop on the itinerary, certainly accepted credit cards.

No, of course I didn’t accept his offer. But every time I see him now, which isn’t often, he says some version of, “You shoulda got the suit.”

Not sure what this says about my wardrobe.

3. Revis deployed intention before that became a buzzword embraced across sports and outside them. The suit store—and Minnie’s chase—were part of a Sports Illustrated cover that ran in July 2015. In some ways, it felt like the culmination of the chronicling.

I had only recently left The New York Times, where I started out as the Jets’ beat writer—and in the middle of Revis’s dazzling rookie season. After nearly four seasons covering the team, and four more covering the NFL from more of a national perspective, I was returning to my NYC writing roots, while Revis, more important, was headed back to the Jets, fresh off winning a Super Bowl with their hated division rival, the Patriots. We spent five days together for the cover story, the time split between a New York trip—taken during a month spent living in Las Vegas in advance of Mayweather-Pacquiao—a Miami check-in (over the phone, before an iconic photo shoot) and in Sin City before the week of the blockbuster bout that May.

Quick oddity reporting summary: The reporting, somehow, involved SI swimsuit models, Dave Chappelle, money guns, escargot, a massive bounty at the craps table, a private plane, a family reunion and many new reveals, as Revis decided to tell the story of his previous five seasons in full, unsparing detail.

Revis admitted he considered retiring after the 2012 season, his last in his first stint with the J-E-T-S. He revealed a meeting with then President Barack Obama, who called him by his famous nickname, Revis Island. He described Bill Belichick’s coaching methods: “Bill was as calculating as I am.”

But intention? This marked one of my favorite graphs in that piece.

Inside the Jets’ training facility in Florham Park, N.J., Revis recognizes an old friend. “Is that Juan?” he asks, spying a janitor down the hallway. “Juan is my dude.” He’s back to familiar comforts and old routines. “It has been a while,” he says of two years away from New York that felt like two lifetimes. “I mean, I’m losing my hair,” jokes the now 30-year-old. “It’s crazy how everything went down.”

4. As far as claims to fame, sportswriters don’t have any, really. But when student journalists, or friends, or strangers at airports inevitably ask for moments in a career with no shortage of them, one of my go-tos is being able to claim the first time, far as I can tell, that anyone used the term Revis Island in print.

Even Mayor Michael Bloomberg once temporarily renamed Manhattan with the moniker. And, yes, of course Revis’s trademarking the phrase spoke to his business acumen—and not in a negative sense.

5. Revis reported to the Jets’ old headquarters on Long Island in the spring of 2007, at age 21, and quickly shifted underneath the oversize spotlight that is the New York media. I arrived at the Jets’ old headquarters that fall, at age 27, wondering whether I could stick, as part of the glare, but more unsure than I’d care to admit. My first week spent in Hempstead featured wrong turns, bad decisions, a botched news break that wasn’t my fault but was botched anyway, wideout Laveranues Coles calling me an idiot in a group interview setting, not entirely without justification, and a strong inclination to fly home to Seattle and never visit New York again.

In one of my first stories for the NYT, a devastating loss to the Bengals, Revis came up near the end, for his mistakes that afternoon, which marked the beginning of our intertwining.

The Jets walked through a tunnel toward their locker room in silence, heads down, bruised, battered and beaten yet again. Bengals fans who lined the tunnel showered them with insults, heckling the players as they passed.

Another Sunday, another loss, another silent and dejected locker room …

Rookie cornerback Darrelle Revis was penalized twice for pass interference. Safety Abram Elam, making his first start, missed a key third-down tackle.

6. This might be impossible to believe now, but Revis went nearly half of his rookie season without snagging a single interception. As with many notions that clung to his career, the idea of a “slow start” was fair but overstated. Those Jets stunk. Opposing offenses avoided Revis like Gang Green avoided beating the Patriots. And, on that Sunday against Cincinnati, Mr. Island lost one pick to a “simultaneous catch penalty” and missed another when officials whistled him for pass interference.

Even then, Revis displayed one trademark afterward. He spoke his mind and said his truth, regardless of reaction. Speaking specifically about the penalty, he said, “I don’t think it was a flag. It was a great play. I didn’t touch the dude at all.”

At the time, it seemed like all professional athletes expressed similar sentiments. But Revis was more self-aware and self-assured than most, if not all, of them.

7. This, he later told me, was what he knew about the Jets upon arrival.

“How tortured their franchise history had been. That it had been a struggle in their organization. That they had only had one Super Bowl. I watched them on TV and really did not see great football played. That’s one of the reasons I said what I said to Mike Tannenbaum, the general manager: ‘I’m going to help you win a championship.’”

Everyone involved was immersed in said torture. But only a few, including Revis, so boldly declared their twin engines—lack of fear and belief in self. He came close. Almost. Not quite.

8. Right away, The Island reminded longtime J-E-T-S observers of Joe Namath. They held a lot in common—both from Western Pennsylvania, both outspoken, both banished to a professional football hinterlands known for bad everything (play, coaching, clock management, bounces, injuries, luck). Both resolved to change the same paradigm, almost 40 years apart. (Side note: How wild is it that the same paradigm remains?)

They first met, Revis Island and Broadway Joe, before the former’s rookie season. From an SI story: There was a Big Brother-Big Sister event that both were scheduled to attend in Pennsylvania. Revis arrived and sat down and saw that the placard next to him said “Joe Namath.” Eventually, Namath arrived and sat down, too. Revis said they both laughed before they said anything. Then Namath said, according to Revis, “We gotta be gentleman tonight. I know we’re rivals, but we’ll save it for later.”

9. The learning curve proved both immense and also conquerable. Revis transcended (circumstances, paradigms, conventional wisdom, stereotypes, boxes) with preparation so thorough it was perhaps more impressive than his play. He spent much of the 2008 season, his second, studying film from his rookie year. This wasn’t a masochistic exercise; it was an instructive one. He needed to look back (and relatively far) to find and correct mistakes. But as he discussed his process—so many late-night meetings with safety Kerry Rhodes, regular check-ins with all defensive coaches—he left the implication hanging. It worked better that way.

He hadn’t made enough mistakes that season for any sort of full review. Hence the trips back in time.

10. My favorite Revis process anecdote. When he was young, an uncle, the longtime NFL defensive tackle Sean Gilbert, told his nephew he needed to “climb into” the psyche of his opponents. Mr. Island followed that directive to an unfathomable conclusion, where, he revealed, he even shadowed the targets he was covering that day when their offense didn’t have the ball. He’d stand across from, say, Randy Moss, and he’d … just … follow him. Stalking szn became a hallmark of his greatness.

11. As a young writer still learning two critical concepts—how to report and how distinct reporting formed the basis for any kind of writing but especially the better kinds—I held little experience with access journalism. Certainly not with superstars. A visit to see Revis in December of his rookie season marked an early foray into the kind of work that I do now. We met at his condominium near team headquarters. I took the train up, nerves swirling. But the conversation flowed better away from the locker room, planting a career arc seed.

WESTBURY, N.Y. — Here in his two-story condominium, the one with hardwood floors and leather couches and a huge flat-screen television, Darrelle Revis is everywhere at once.

He is on TV, No. 24 in the white Jets jersey guarding Randy Moss, body twisted in midair to secure the third interception of his rookie season. He is on the football cards from Upper Deck, a full 799 stacked on the coffee table. And he is on the couch, Revis in the flesh, scribbling his signature with a Sharpie.

“This is nothing,” Revis said during an interview Tuesday. “I signed 4,000 once …”

In a year defined by change, in a season worthy of defensive rookie of the year consideration, two constants serve as guides for Revis.

“Football,” he said. “And family.”

Sadly, I’ve used both the everywhere-at-once and constants-in-sea-change concepts several times in the years since—and fairly recently. Which means Revis evolved much better than I did …

12. The Island took an unflinching view of his hometown, which is rarer than it sounds. Most are afraid of offending those they’ve left behind, and much of Revis’s family still lives in Aliquippa. Back then, almost all his relatives did. So, yes, he discussed blue-collar work ethics and high school sports emphases. But he also didn’t shy from gangs, drugs and shootings. He spoke openly of friends, like Ricky Gilmore, he lost to gun violence. Back then, though, he saw those incidents as no more than his everyday life.

13. In October 2008, I went to see Revis in Aliquippa, during the Jets’ bye week. The same duality was present.

There was the place that shaped gridiron glory …

ALIQUIPPA, Pa. — The hill atop Seventh Avenue overlooks rows of rundown and abandoned houses, followed by tree clusters that rise in the distance until interrupted by the black-and-red bleachers of the Aliquippa High School football field.

Before Darrelle Revis was old enough to attend games, and long before he became the Jets’ shutdown cornerback, he stood outside his childhood home here most Friday nights, alone in the silence of a town that shut down for every football game.

“All I thought about was playing there,” Revis said. “When those lights come on, everybody in this town is there. That field is what keeps this town going.”

And the place, the same place, that threatened to unravel every star’s young dreams …

In fact, Revis maintained he made it because of Aliquippa, not in spite of it. Because of his family full of athletes, who were born here, raised here, and, for the most part, still live here. Because of the athletic tradition at his school and in his town.

Above Seventh Avenue, a path leads to the Griffin Heights apartment complex. Revis said one of his uncles belonged to a gang there. Revis always bugged his uncle about letting him tag along, and after months of cajoling, his uncle finally relented. What Revis saw stopped him cold. He said he never went back after that.

Others chose the gang path, like the friend Revis and another uncle, Jammal Gilbert, discussed recently in the kitchen of the house the family lives in on Broadhead Road.

“I heard he’s missing a leg,” Revis said.

“Blown off,” Gilbert said. “He’s got a nub.”

“Wow,” Revis responded, shaking his head.

“That’s what a 40-caliber will do for you,” Gilbert said. “Take a limb right off, boy.”

On the tour, Revis steered his rented Cadillac into another apartment complex called Linmar Terrace. As he explained the inherent dangers there, another car pulled up and a man walked from a stoop to that car, and an obvious exchange took place …

“Like, you know how on any given Sunday you can lose a football game?” Jammal Gilbert said. “Any given day here, you can lose everything. And I’m not talking about just what’s in your pockets.”

Both made Revis into his own island.

14. Two influences stand out for Revis above all others. One is Gilbert. The other is his mother, Diana Askew. Both shaped NFL history in their own way, through him.

15. It’s hard to recall a modern player who shaped the business of NFL history more than Revis. All current players who are holding out, insisting they be paid what they’re worth and no less, while “fans” rain death threats upon them through social media, owe him at least a thank-you card and probably more like a good bottle of vino.

Of all the sentiments applied to Revis, this is the most problematic. He wasn’t, as often described, a pure mercenary. Just ask Gang Green. Yes, he did hold out, and more than once, and the better he played, the more each subsequent absence resembled a circus that was partly of his own creation.

The best detail from those holdouts, for anyone familiar with the drive down Route 17 from Central New York toward the five boroughs: The meeting that clinched the end of Holdout 1, in 2009, took place at a fairly typical meeting spot along that route. The Roscoe Diner.

16. The best quote, from all Revis holdouts, came from an expected source. “Somebody will kiss him on the lips, probably,” Rex Ryan said, whenever Revis came back to his island.

17. Writers, broadcasters, pundits, analysts, anonymous NFL sources and the least forgiving of pro football fans often saw Revis as selfish. A nickname even circulated in those days, morphing Revis Island to Me-vis Island. I always found that crucible odd yet understandable. The Jets’ fan base is supposedly blue-collar, working types at its core. The Jets’ best player in those days wanted to be compensated for his value. None of those workers who cheered Gang Green would have accepted less than full payment for their toiling. But because Revis’s compensation was obviously and dramatically higher, they expected him to do what they never would.

His teammates, meanwhile, saw the NFL for what it is: a multibillion-dollar enterprise where every player is an asset, and every asset, no matter how loyal or how valuable, can be discarded, whether easily or with faux expressions of heavy hearts in public settings. When Revis tore an ACL and missed most of 2012, the Jets shipped him to the Buccaneers, and if there was any outrage, it certainly didn’t make much of a dent in the public perception. He won a Super Bowl in New England, but it’s not like the Patriots bent their famous way to bring him back for another run. Just like no one demanded loyalty for his service. Players knew this.

From running back Leon Washington, who wanted a new contract after his 2008 season, was forced by the Jets to play the next year on a below-market deal and then broke his leg in October (NYT, ’10): Washington said his 2009 experience “absolutely” played a role in Revis’s situation. Told that it also appeared to have an effect on the Jets’ locker room, he added: “I’m close with all the guys over there, so we still talk often. They have lives, too. The situation there in New York, that’s their situation. I’m in Seattle. I’ve got a whole different outlook. When it comes to Darrelle, obviously, my situation makes them think differently.” …

“… A guy like Darrelle, an older guy going into his fourth year, he saw examples of me, what happened, and I think he’s just trying to learn from it.”

18. It’s not hyperbolic to say that Revis shifted some bargaining power back toward elite players. For anyone to replicate his strategy of staunchness, they needed to be indispensable, so their holdouts could threaten to upend seasons, sink franchises and, let’s say the quiet part out loud, cost decision-makers jobs.

Revis was a mercenary, but for all the right reasons. He just had the temerity—THE TEMERITY!—to approach football through two distinct lenses. He wanted to win as many championships as possible … and make as much money as teams would pay him in the process. Those concepts were not, are not and will never be mutually exclusive.

19. After leaving the Jets’ beat in Ben Shpigel’s brilliant hands after the 2010 season ended in a second straight AFC championship game loss, I still regularly covered games, mostly through columns, and occasionally trekked out to the old office. It seemed—speaking for myself here—that perception was hanging on Revis’s shoulders like a weight he didn’t love to carry. He came across a little more surly with reporters. He snapped in public more often. I saw this as tied to his fame, which had ballooned, making him perhaps the most famous nonquarterback in football, which automatically made him one of the most celebrated athletes in all of sports.

He was still a human being, within that. He heard what people said about him. He tried to understand their viewpoints. His dominance began to fray, just slightly, through age and injuries and a cumulative toll. He still had a reputation to live up to, an island of defensed passes to maintain. He needed a new paradigm. And, to obtain that, he needed a new role.

20. We built the perfect cornerback once, me and Mr. Island. Yes, I realize this is a trite concept that’s fairly common in sportswriting. I’d like to think we were ahead of the trend. I’m probably wrong. Revis’s ideal, though, is pretty fascinating. He chose the footwork of his idol, Deion Sanders; the field vision of his “big brother,” fellow Aliquippa native Ty Law; the speed of Darrell Green; the hands of Champ Bailey; and the athleticism of Charles Woodson.

Which means—and this is, admittedly, a little hyperbolic—Revis created a version of himself. He was a complete shutdown corner who completely shut down wide swaths of NFL fields. Maybe he wasn’t as fast as Green, or as athletic as Woodson, or as sure-handed as Bailey. But Revis really did it all. He was so dominant for several seasons, in fact, that he continually was overlooked for awards like Defensive Player of the Year. Voters considered things that are important, like interception tallies and overall statistics. But they missed the nuance that gave Revis’s game a poetic bent. Dennis Thurman, the Jets’ defensive backs coach in those years, once told me that Revis played single coverage on roughly 67% of the team’s defensive snaps. Meaning that, for 67 out of 100 plays, Gang Green could send another player elsewhere, into another part of a field already condensed by The Island.

Anyone who described Ryan’s defenses in those days as creative and scheme-wrecking should have known what’s now even more obvious. Revis, more than any other player, made them so.

21. That said, Uncle Sean never let up. From the NYT, in 2009:

“We’ve got a long way to go,” [Gilbert] said. “Right now, Darrelle is a dune buggy. We want him to become a racecar.”

22. In his later years, Revis became an elder statesman. He lobbied for offseason additions with more than one team. He invited young defensive backs to endure his grueling offseason training slate in Arizona. And he led—yes, led—the Patriots to that Super Bowl XLIX triumph over the Seahawks, after escaping Tampa Bay after one season.

I resumed writing about his career in early 2015, having left the NYT for Sports Illustrated roughly a year earlier.

This, from their AFC championship game triumph (also known as the day that sparked the dumbest controversy in league history, Deflategate):

The music stops, the Patriots’ locker room empties, and Darrelle Revis stands at his cubicle in Gillette Stadium, in no rush to leave. It took him eight NFL seasons to reach this moment, to soak in the aftermath of an AFC championship, all the fireworks, the defensive linemen dancing around shirtless, the silver trophy serving as a prop in an endless string of selfies.

Revis wears a wool sweater, red sneakers, a full beard and the look of a veteran who has seen it all. Almost, anyway. Six seasons with the Jets passed like a Lifetime movie, with two AFC title-game losses, a contract holdout, an ACL tear and the nickname that he trademarked, Revis Island, for the cornerback who makes receivers disappear. After a lost season in Tampa Bay, Revis signed a one-year, $12 million deal (with a team option for a second year) with his former rivals last March. The goal was clear: Super Bowl or bust.

As the crowd around Revis’s locker dwindled, he came back to one key moment and the prediction that preceded it. Late in the third quarter, with the Pats leading by 24, the defense huddled on the sideline. Someone asked, “Who’s going to make a play?”

“I am,” Revis told his teammates. “Next drive.”

Facing third-and-5 from his own 40, [Andrew] Luck forced a pass near the right sideline to receiver T.Y. Hilton. Revis, who recognized the call and guessed Luck’s intentions, snagged the throw and sprinted 30 yards to set up yet another touchdown. That’s why Revis signed with New England. That’s why the team signed him. “I called it,” says the cornerback turned clairvoyant.

This supposed mercenary, me-first, cared only about himself, fit perfectly in New England. That was obvious all along, at least to anyone paying attention.

As for the Malcolm Butler interception in that Super Bowl, Revis’s first and only triumph? “I thought they were going to run the ball,” he said.

23. I found it wildly interesting—and indicative of immense growth—that Revis later told the I Am Athlete podcast that, after retiring, he was diagnosed with PTSD. He was using cannabis and focusing on his mental health. He had even tried mushroom gummies to clear brain fog.

Most interesting: He attributed his symptoms not to head injuries—he certainly had his share of concussions, whether diagnosed or otherwise, including one 39-month stretch with four diagnosed head injuries—but to his childhood. What a gift, to be able to see that and recognize that. It made all the sense in the world.

24. Imagine going to college and meeting one of your best friends. The biggest knock on this dude, a prince of a human being, is the obvious one. He’s one of the unreasonable ones, tethered not to glory nor community in sports fandom but to angst and heartbreak, with a native New Yorker (over)bearing and a heavy dose of sarcasm after more than a few Bud Lights.

In other words, he is a Jets fan.

Imagine coming back to New York, and covering his favorite team—all the questions, text messages, overreactions and unsolicited amateur punditry. Then imagine coming back, again, for a photo shoot, to recreate one of the most iconic covers in the history of Sports Illustrated, in Times Square, with one of this buddy’s favorite all-time Jets.

You’re welcome, Joe (Kanakaraj, not Namath). What a day that was. Police barricades. Namath echoes. Diana in town to witness everything. Revis in full uniform, the day after he offered to buy that suit. Worlds colliding. It was one of those moments, where you’re there and not there all at once—(told you, see: No. 11)—where you realize something special is happening, and you simultaneously speed back over everything that led to it. The original SI office copy of the Namath cover still hangs in my home office.

Because they all age, certain athletes become markers for our lives, for a blissful, if brief, time period, one we want back as much as they do. For what they did, what they taught and what they transcended—and, most of all, for the up-close vantage point to greatness, the kind that’s as rare as a man with his own island.