How an NFL Sideline Works: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Dolphins’ Support Staff

“What’s Metallica without a guitar?” Mike McDaniel asks.

The Dolphins’ second-year coach is speaking hypothetically about the essence of what makes a band, but also more generally about the people and objects that make up any group defined by the way it performs. “Probably not selling albums,” he adds.

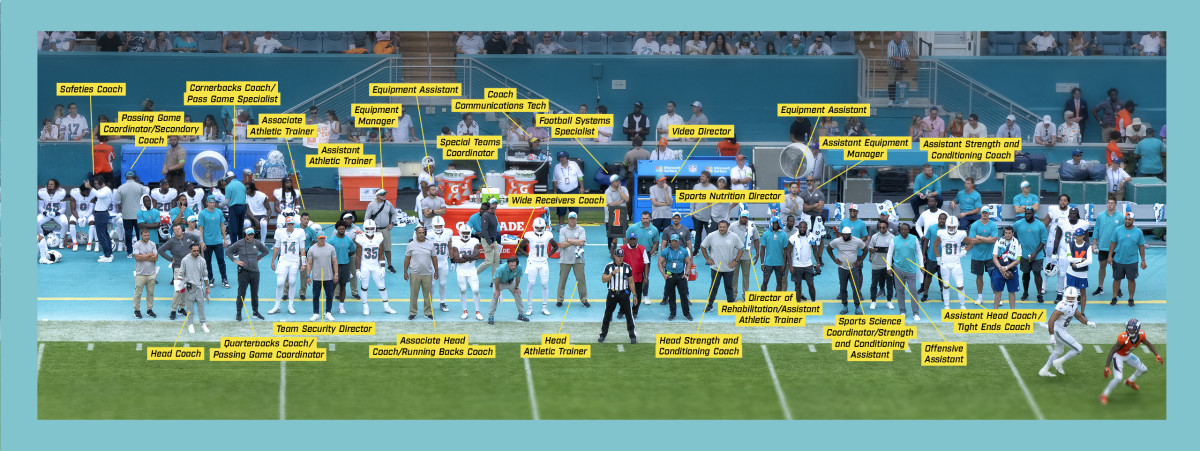

The head coach sets a football team’s culture. That’s true of McDaniel and the 31 others in his position across the NFL, each of whom are spokespeople, managers and decision-makers on issues large and small. They typically receive the credit when a team sees its fortunes turn around, and the blame when it doesn’t.

But the truth is McDaniel is reliant on an army of people surrounding him on the org chart, many of whom have been with the Dolphins significantly longer than he has. They are “head coaches of their own departments,” as he puts it. Some of them have been in place for decades. He can appreciate their behind-the-scenes dedication, having started his career in the equipment room as a Broncos ball boy.

“People don’t really understand what type of commitment that is to be on a seven-day-a-week program,” he told SI in September of his vast support staff. “So it’s awesome when the team finds success, because you find those people are doing it for the right reasons.”

Four days later, his Dolphins stomped the Broncos by 50 points in their home opener. They set an NFL record with 726 yards and became the first team to score 10 touchdowns in a game since 1966. They could have broken the all-time scoring record of 72, if not for a merciful kneeldown from within field goal range on their final play.

We take a lot in sports for granted, but the logistics, tech and teamwork behind our favorite games and events all are fascinating. Sports Illustrated's How It Works series goes behind the scenes to find out how it all comes together.

How an F1 Track Works: Turning the Vegas Strip Into a Racetrack

How Building an NBA Arena Works: Inside Clippers’ New Home

When we started this project, we didn’t know the Dolphins would be one of the most prolific offenses in NFL history. We chose them to offer a portrait of an ordinary NFL Sunday, then witnessed one that was anything but. The goal was to spotlight the support staff, the essential sideline personnel, the unsung heroes of not just game day but every day across the NFL.

Looking back on that day of glowing afternoon sunshine, in which Miami temperatures reached the high 80s and the Dolphins’ point total nearly followed suit, the pummeling was less like a rock anthem and more like a sweeping orchestral performance. This is what it looks like when the tiny details fretted over and unseen grunt work at odd hours all pay off. When every member of an ensemble hits just the right notes.

The Tech Guru: Patrick Oliver

With Dolphins Since: 2016

Four hours before kickoff, Patrick Oliver arrives at the stadium and finds the man in the purple hat.

On an NFL sideline, the “purple hat” is the league representative in charge of the Microsoft Surface Pro tablets that fans see coaches furiously jabbing and, sometimes, Tom Brady spiking into the bench. Oliver is there to make sure the tablets are operational and meet the requirements of the Miami coaching staff, which include one important note: The Dolphins do not like to have the stylus pens attached to their tablets. The strings are too likely to get caught on something, and in only very cold weather, when players’ gloved hands will not activate the touchscreen, will they ask the purple hat to keep the pens attached.

Each team is allowed a maximum of 16 tablets per game, and Oliver lets the league know that Miami will take the full allotment. Two of their coaches still prefer to look at in-game all-22 photos the old-fashioned way, so Oliver and his crew have a printer on the sideline. A runner staples photos together and sprints them to coaches who need them. (The team would not confirm which coaches still prefer printouts.)

Oliver and his team also confirm the reliability of data transfers from Mike Nobler and his film crew. What players and coaches see on tablets is, essentially, a series of still photos taken during the all-22 filming process. Additionally, this season players and coaches are able to see statistics on the Surface tablets for the first time. Oliver says it takes roughly 10 seconds from the completion of a play until the moment the still photographs are ready.

As Miami’s football systems specialist, Oliver’s job is to always be on; he admits that “caffeine doesn’t really work for me anymore.” On any given day he might have to figure out why an office computer isn’t functioning (paying special attention to Mike McDaniel’s space-age 55-inch curved monitor desktop, which allows him the most possible screen space), or why the Wi-Fi has become spotty on sidelines since COVID-19 hit. The reason: The benches were spaced out a few additional yards to prevent close contact, but no one accounted for the reach of the Wi-Fi.

“Right at the 50-yard line there’s two antennas,” Oliver says. “They’re both pointing out, so, right where they cross at the 50, your tablet jumps back and forth [between Wi-Fi feeds], and it feels like it’s a dead zone.”

Coaches in Miami exist in various inhuman sleeping cycles, with some staying in the office until 2 a.m. and others opting to arrive for work at 3 a.m.—which means someone from Oliver’s staff always needs to be near their phone. Asked whether he’ll receive more than a dozen post–10 p.m. phone calls per season, he says, “Definitely.” When Oliver was on a honeymoon cruise to Iceland and Ireland with a week in Switzerland added on, he says, “I was in the middle of the ocean getting phone calls. . . . It’s just part of the business. My wife understands it.”

He can sound as much like a linebacker as an IT specialist: “Every department in this building is grinding nonstop for one game a week, for as long as we can go. The playoffs last year definitely, I think, increased that hunger to go farther and do better. If it requires working more hours, we work more hours.”

The hardest part is finding vendors that are not used to the rigors of professional football but are willing to keep up with an NFL schedule. “I was just talking with a vendor, and they were like, ‘We’re ready to do the install,’” Oliver says. “I was like, ‘Well, your hours to do the install are between 1 a.m. and 2 a.m.’ They were like, ‘We’re going to need to reschedule.’

“I was like, ‘You let me know when you’re available during that time of day, and we’ll make this work.’”

The Healer: Jasmin Grimes

With Dolphins Since: 2018

There are at least 16 ways to tape an ankle, Jasmin Grimes says. It’s her job as an assistant athletic trainer to know which way each Dolphins player prefers. Some want the tape a little higher, others a little lower, some a little looser or with a little extra tape here or there. And, to give away an industry secret, some players want certain body parts taped only because it looks cool. “If you look good, you feel good, you play good,” Grimes says.

The secret to a good tape job, like most things in pro football, comes down to reps. Grimes has been with Miami for six seasons now. Most players have a go-to trainer, and she says building relationships with the ones she considers her guys has gone a long way toward understanding how best to get them ready to take the field. That includes everything from taping ankles and wrists to cutting T-shirts just the right way to fit under shoulder pads.

Pro Bowl linebacker Bradley Chubb says after he was traded to the Dolphins in the middle of the 2022 season, he tried out tape jobs from every trainer and quickly became one of Grimes’s regulars. “She did it perfect the first time,” he says, “and it’s been like that ever since.”

Grimes played basketball in high school and grew close to her athletic trainer as she dealt with a few injuries. When she arrived at the University of Maryland, she hoped to work with the women’s basketball team, but those trainer jobs went to the most experienced students. She made the move to football instead, where the Terps’ head coach, Randy Edsall, had been Grimes’s father Roland’s position coach when he played fullback at Syracuse in the ’80s.

When Grimes was getting her master’s in athletic training at FIU in Miami, the Owls’ head trainer, who had worked for the Dolphins, placed a call on her behalf. She started as a summer intern in 2018 and worked her way up from there. Her final year as an intern was the ’20 season, when the pandemic wreaked havoc on everything. The team gave Grimes COVID-19 liaison duties, putting her in charge of all sorts of protocols, from keeping track of testing results to notifying players of contact-tracing concerns.

Watch the NFL with Fubo. Start your free trial today.

Her list of responsibilities has only grown, now including everything from working out rehabbing players to driving the injury cart. Yes, when a player needs to be taken to the locker room for X-rays during a game, it’s Grimes behind the wheel. Forget about a road test; she didn’t even get a test drive. Her first time driving the cart came in a full stadium, where any mishap would surely find its way to social media. So far there has been only one minor incident, a video of her that circulated online after she had to yell at people to move out of the cart’s way.

As the first woman to become a full-time athletic trainer on the Dolphins’ staff, Grimes is cognizant of how her role matters. “Sometimes it only takes one, and I think it opens doors for a lot of women behind me,” she says. It’s something she talks to her boss about as they try to include women among their interns every summer.

When Grimes started out, she used to keep a list of every female athletic trainer in the NFL, saying it was important for her to make that list someday. She guesses there were around six in 2019, with the number of Black women like her even smaller. Numbers have grown in both regards across the league in recent years.

When she’s not driving the injury cart, taping body parts or dressing wounds, Grimes can often be found worrying about players’ hydration levels, a vital task in Miami’s heat. One crucial element of her job: when players start cramping, knowing who will want Pedialyte and who will want pickle juice, both of which are kept in small coolers in front of the Gatorade. Fortunately, players don’t seem to care much about which color the Gatorade is, though the team avoids red for two critical reasons. One, some players are allergic to the dye. Two, a red stain on a white jersey could be confused for blood.

“Sometimes you have to force them [to drink],” she says. “But a lot of times if a player comes off the field, we just kind of put it in their face a little bit. It’s almost like thinking for them and knowing what they need before they realize they need it. I’m thinking two steps ahead.”

The Producer: Mike Nobler

With Dolphins Since: 2015

Last Season, in the Week 18 game against the Jets that would seal the Dolphins’ playoff berth, the coach-to-quarterback headset went out.

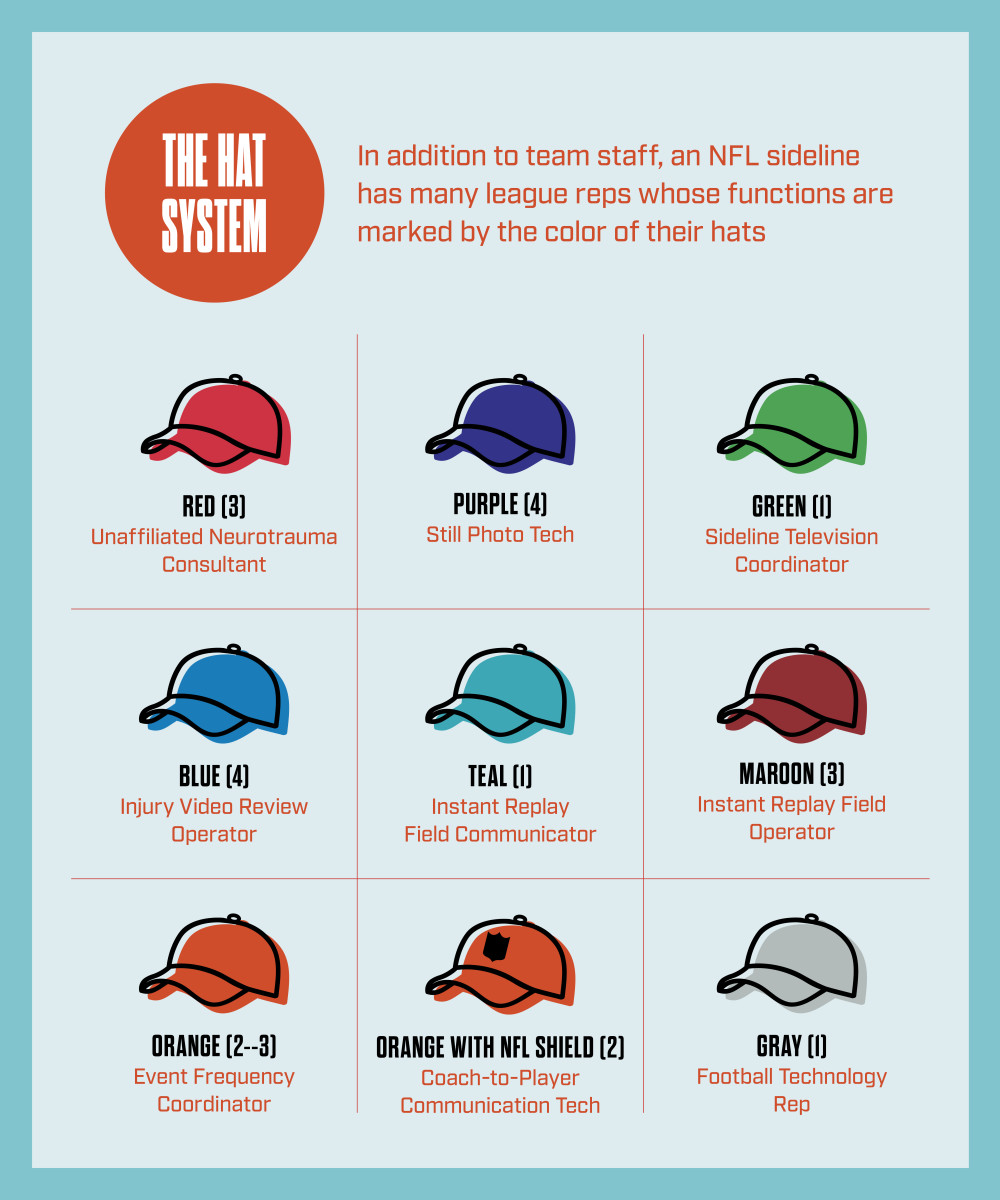

The NFL has standardized frequencies in each stadium to ensure that radio communication does not go haywire and a frequency coordinator to oversee the system (known as an EFC, identifiable on the sidelines by an orange hat). But on that day, somehow the frequency the Dolphins were using for coach to player got jammed up. It wasn’t unheard of. Once before, a nearby Sunday school turned on a device that bled into the stadium’s network.

Enter Mike Nobler, the Dolphins’ video director. “In that moment Coach McDaniel isn’t like, ‘Mike, take the time you need. We’re going to just call a 15-minute timeout and we’re going to figure this out,’” he says.

Nobler got on the phone with NFL HQ while running through a troubleshooting checklist. Did the other team also lose headset access? Is it just the quarterback’s helmet, or is it the defensive player wearing the green dot, too?

Then he had to enact the team’s backup plan, a handheld walkie-talkie that neither McDaniel nor his defensive coordinator was familiar with. But first he had to check in with the EFC to confirm that the walkie-talkie would cut off coach-to-QB communication with 15 seconds remaining on the play clock, just as the helmets are required to. “At that moment it’s like, oh my God, this is a win-and-you’re-in game. And right now a coach can’t communicate with the quarterback on the field. That’s a pretty big deal,” Nobler says.

Headset troubleshooting isn’t even Nobler’s main job, but as video director he’s intimately connected to the lifeblood of any team: the offensive and defensive play-calling system. Nobler, who has been in his role for the past nine years, often gets mistaken for the person who makes video elements for the scoreboard. In reality, he and his staff record every game and practice, and marry that footage with data (down, distance, time, players involved, opponents faced, situation on the field, etc.) so that time-crunched coaches can pull up any clip they need at a moment’s notice. He has a film library with almost every conceivable moment of Dolphins football since 2008 on a server somewhere. There is additional footage on there going back to 1984.

Coaches will ask Nobler and his staff for individual projects. Since the video of each game that all 32 teams shoot and upload to a central database comes with only a few generic filters (down, distance, etc.), his staff works with numerous third-party vendors and its own in-house data hub to apply more sortable variables.

“If we walk in Monday at 6 a.m. and you say, let me see all two-point conversions from the weekend, done,” he says. “Let me see all fumbles; let me see all forced fumbles; let me see all interceptions; let me see all touchdown runs when teams were in 22-personnel. We can do all that.”

When Nobler isn’t trying to solve some frequency outage in the cosmos on game day, his staff of three films every play from three different angles: the all-22 angle, which is a wide shot taken from high above the 50-yard line so every player is in every shot, and then two end-zone angles, taken between the goalposts, directly in the middle of the hashes. This season is the first year that the Dolphins are shooting both end zone angles. Nobler is the kind of person who gets excited about discussing the ethics of whether plays that aren’t run (a QB calling timeout at the line, for example) should be included in the standardized video log.

“There’s a whole rule book on how many cameras we can have, what type of camera we’re shooting, when we start and stop a play,” Nobler says. “So you’re not excluding certain things. You can’t exclude motions and shifts. You can’t manipulate the video into a way to make it seem like we didn’t do something like, ‘Oh, we ran this great fake punt. Oops, we didn’t include that for Denver to see.’ You can’t do that at all.”

One member of Nobler’s staff will edit the video live as it comes in, play by play. Another will edit and manage still shots of the video, which make up the bulk of the content contained on the blue Surface Pro tablets players and coaches look at on the sideline. After the game the footage will be immediately uploaded to the NFL’s centralized Club Game Exchange.

If all goes according to plan, by the time McDaniel reaches his car or bus seat after a game, he can watch what just occurred in almost any way possible, sorted through any of the 350 data filters Nobler and his team have facilitated. If there is something McDaniel wants that is not yet available, such as every play where his upcoming opponent’s star defensive tackle is lined up just a shade to the left of the center?

“It’s like, O.K., give me a minute to think about how we’re going to do that,” Nobler says. “And then we do it.”

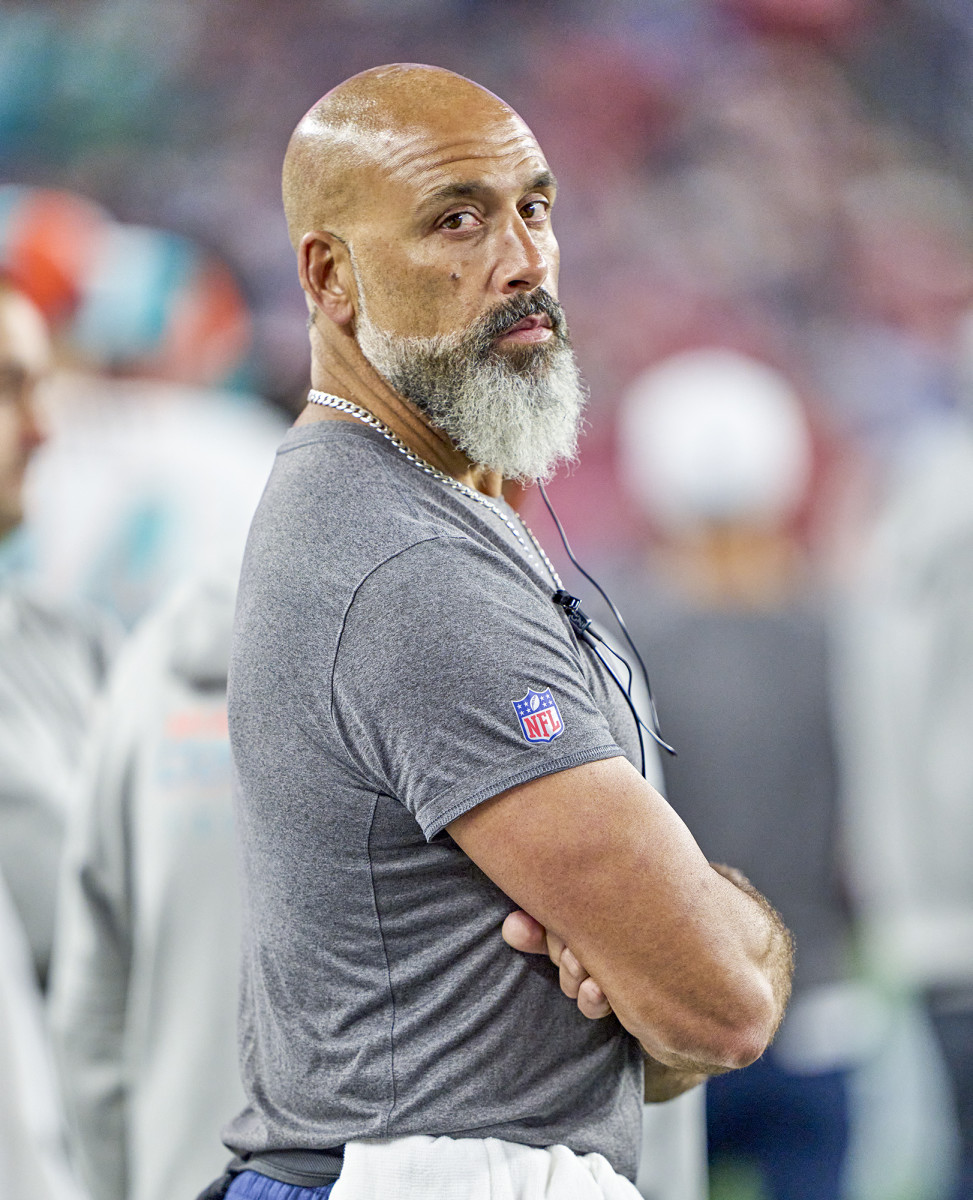

The Supporter: Adam Lachance

With Dolphins Since: 2015

On game-day morning, Adam Lachance wakes up at 5:30 a.m. and makes a critical stop before arriving at Hard Rock Stadium to begin his duties as assistant strength and conditioning coach: McDonald’s.

Breakfast burritos have been part of his game-day routine for most of the nine years Lachance has worked with the Dolphins. Before that he was a proud Army man for nearly seven years, serving out of Fort Bragg in the parachute infantry regiment. He did three tours in Afghanistan and one in Oman. His job was to attach with a sniper or special operations unit and call in aircraft support if his team was in a firefight.

So football responsibilities aren’t all that daunting. “I couldn’t see myself in a field where there’s a lot of I can’t,” Lachance says. “If you can help someone reach their goals, you get a lot of fulfillment from that.”

Before kickoff, Lachance is in the building working out the practice squad. Then he’ll assist players with stretching or the active release technique, which helps with soft tissue manipulation. On the field, he is monitoring the landscape. Some players have strict warmup routines that he doesn’t want to interfere with. Others could use assistance.

His size—in high school he dabbled in bodybuilding and he still looks as if he could stack boulders one-handed—and personal touch make him an ideal “get back” coach: He’s responsible for keeping players from surging onto the field and incurring penalties. Lachance has learned which players and coaches respond best to shoves and taps, though sometimes he has no choice but to body-wrap someone like a pro wrestler.

“They’re usually O.K. with it,” he says. “No one wants a 15-yard penalty.”

The Protector: Larry Juriga Jr.

With Dolphins Since: 2000

The first thing you learn about subduing a fan who’s run onto the field: Don’t chase them. So says Larry Juriga Jr., a 6' 4", 300-pound, second-generation Dolphins security guard. Unless they’re running directly at a player, of course. But if not, “You let them get tired and then go grab them,” he says.

Juriga is authorized to use necessary force, he says, but it happens less than you might expect. It’s more common that he has to protect the sideline from projectiles. When the Dolphins traveled to Buffalo for a prime-time game last December, he found himself batting snowballs like a rim-protecting center swatting away finger rolls.

“Sometimes fans get silly,” he says. “They’re not looking to hurt anybody, I wouldn’t think. They’re just looking to be a bother.” Juriga says his concern is not just the obvious—player safety—but the scoreboard as well. “The players are trying to focus on the game and focus on what the coaches are telling them,” he says.

Juriga was born and raised in Miami. His father, Larry Sr., worked for Hard Rock Stadium (then known as Joe Robbie Stadium) when it opened in 1987, then later worked directly for the team. Larry Jr. got a job as a 16-year-old high school student, working field security for the company contracted by the stadium. Now 52, he says his father “was and is still my best friend,” including best man at his wedding. He followed in his dad’s footsteps in more ways than one, first becoming a policeman at the North Miami Police Department, then officially working for the Dolphins starting in 2000. He rose to chief of police, but is now full time with the team after retiring from the force in March.

Juriga stands guard on the sideline only during away games. For home games he has another vital task. After Mike McDaniel has arrived at the stadium on game day, Juriga will drive to the coach’s house to take McDaniel’s wife, Katie, and family to the stadium. He then stays in their box during the game. It may sound menial to some, but there is an earnestness in the way Juriga describes the importance of this job. “If Coach McDaniel doesn’t have to worry about his wife getting to the game, if he doesn’t have to worry about where they’re at, he can focus on taking care of the team and what he needs to on the field.” This is what it looks like when everyone in an organization feels invested in winning.

Juriga’s deep knowledge of the stadium and surrounding complex has led to other interesting assignments. On the night of Super Bowl XLI, when the Colts beat the Bears in 2007, Juriga was attached to a VIP: Roger Goodell. As the first-year commissioner glad-handed at various appearances in the parking lot pregame and then traveled up and down from his suite, it was helpful to have someone who knew his way around.

For road games Juriga is part of the crew that screens luggage before the team boards its bus, essentially serving as TSA to hasten the process of flying home. This has been a particularly busy season thanks to the team’s Nov. 5 game against the Chiefs in Frankfurt, Germany. Planning meetings started months in advance, including an offseason trip for many staffers to get the lay of the land. “Step on the bus, step on the plane in one country, step off the plane in another country, get on the bus and go directly there,” Juriga says. “That doesn’t just happen by chance.”

The Problem Solver: Drew Brooks

With Dolphins Since: 2016

At halftime of the Dolphins’ Week 2 win over the Patriots, a smirking Mike McDaniel finished his interview with NBC sideline reporter Melissa Stark and started jogging toward the tunnel in stride with a muscular member of the team’s support staff.

After a few moments, McDaniel said something to the staffer and worked himself into a full sprint. The coach, a former wide receiver at Yale, kept looking backward as he left his coworker behind.

That staffer was Drew Brooks, director of team security. “Mike was a lot faster than I was expecting, to be honest with you,” he says of the moment that went viral. “I’m not as young as my mind says I am.”

Brooks is 52 but looks like he could enroll at the University of Miami tomorrow and convince someone he has eligibility as a linebacker. For two decades he was a police officer in Pembroke Pines, Fla. He spent time on the SWAT team, investigated auto thefts and murders, and served as the department’s union leader. On game day, McDaniel is his primary responsibility. Brooks is the coach’s body man and personal “get back” coordinator. It can be a unique experience. At one stressful point in the Patriots game, McDaniel looked at him and said, “Nice sneakers, dude.”

“Then he walked away,” Brooks says. “That’s just how he is. You don’t know what’s going to happen next, so I love it.”

The night before games, Brooks is responsible for doing the team’s curfew check. (Miami’s curfew varies by situation; it’s not a set time every week.) The morning of a game, following his 6 a.m. workout, he gets to the stadium to check off that every member of the team has arrived. Tardiness is a fineable offense.

From there, Brooks attends the NFL’s 100-minute meeting, which, for a 1 p.m. game, usually lasts from 11:20 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. There, team security officials and referees go over the protocol for any interruption, such as an intruder on the field or, more recent, the presence of a drone in nearby airspace.

There is always something for Brooks to keep tabs on. Thanks to the contacts he has through his police work, Brooks will be called on to expedite the acquisition of passports or take care of other delicate details. A security director takes the kind of calls no one else in the organization can. One recent example: a threat levied against a player on social media. “We don’t take anything lightly and [we] look into it,” Brooks says.

Being part of the organization is a dream come true for a lifelong Dolphins fan. “When I was 14 years old, I stood in line two hours to get Dan Marino’s autograph,” Brooks says. Now the Hall of Fame quarterback (and special adviser to team owner Stephen Ross) will call him up, and they’ll go to dinner. “Never in a million years did I think that would ever happen,” Brooks says.

Game day can be chaotic—with so many people around and the possibility for so many unexpected things to happen—but that’s when Brooks lets out a sigh of relief. Throughout the week, he must be everywhere and nowhere, hidden and available. “Getting to the game itself, it’s like the job’s done for the week,” he says. “We have everybody there and accounted for on the field. The game is my kind of peace.”

The Messenger: Renzo Sheppard

With Dolphins Since: 2016

When an injured Dolphin is announced as questionable to return, you’re probably getting the news through Renzo Sheppard. As football communications manager, Sheppard, who goes by Zo, is tasked with getting information from field level up to the press box.

Cellphones are prohibited on NFL sidelines, so Zo uses the big blue phone bank at the 50-yard line. Each handset can call only one destination—like, say, the press box—so you don’t have to dial. When someone upstairs needs to reach the field, the bank lets out a hideously annoying ringtone.

After an injury, teams are required by the league to share the player’s name, body part and designation (questionable, doubtful or out). So when a player is getting looked at, Sheppard, a Jacksonville native who got his start with the Jaguars before joining the Dolphins in 2016, stays close to the athletic training staff for an update he can phone up to the PR director. During his first game in Jacksonville, he was the victim of a prank when someone on the team staff told him a player had a bruised Fallopian tube, just to see whether Sheppard would relay the message. He did.

Another of his jobs is tracking down milestone footballs that might be of interest either to players or the Hall of Fame. Postgame, he helps wrangle players for interviews. Fans are familiar with the prime-time crews setting up desks on the field and getting stars to sit down after a big night. You can add in interview requests from local radio, Telemundo and more. Sheppard helps direct who needs to go where.

The Gear Head: Charlie Thiele

With Dolphins Since: 1994

If everything goes according to plan, game day is Charlie Thiele’s quietest time of the week. And if that’s the case, it’s a testament to how much prep work has been done in the days leading up to kickoff.

The life of an assistant equipment manager is one of endless checklists and contingency plans, knowing which player likes which type of helmet, cleats and other accessories. When something happens in the heat of the game—such as a player coming to him and saying, I’m slipping, what do I do?—Thiele knows, Hey, we already spoke about this. He is ready with different types of cleats for different surfaces or weather and backup plans for everything.

For helmets, Thiele’s team takes 3-D scans of new players’ heads to customize the insides—always a busy day at rookie minicamp. He then works on those helmets every Tuesday, sanitizing them in an ozone machine and checking all the face masks, which need to be in place to withstand hits in practice. Then he changes them all out on Fridays so every player has a brand-new face mask on game day.

Thiele studies pieces of equipment many take for granted. “You don’t know if a chin strap’s about to break,” he says. “We try to stay ahead of it. If you do see something break, I like to think it was new to start on game day and whatever happened out there was pretty bad for that to happen.”

The packing list for road games is huge. The gear needed for the Week 1 game in Los Angeles was dwarfed by an August trip to Houston that featured days of joint practices leading up to a preseason game. It was Thiele’s job to know which items could go in the multiple trucks the team sent ahead and which items needed to fly in. Thiele has to remember to ask other teams whether they have an extra blocking sled. If not, the Dolphins might bring their own.

Packing up a team and moving all of its belongings is a massive undertaking. “We have up to 40 trunks,” Thiele says. “And then the trainers might have 15, 20 trunks. Video might have 15, 20 trunks.”

And packing them is only half the battle.

“Each trunk has X, Y, Z in it, one, two, three, in the same order,” he continues. “So when a guy asks for something, I could say, ‘It’s that trunk over there, number 34, third drawer down.’ On game day, it’s five seconds. ‘Here it is.’”

A 1 p.m. home Sunday game, like Week 3 against the Broncos, is a relative piece of cake—though it still starts with Thiele’s customary 4:45 a.m. wake-up time so he can meet the trucks by 6 at the team facility to move things next door to the stadium.

Home or away, he spends game day scanning the bench and watching players come off the field. “If I see a guy come off and he’s fiddling with his chin strap, I’ll go over to him. ‘Do you have an issue, or are your gloves getting caught and you can’t do it?’” he says. “Or he’s looking at his shoes, or his shoes are untied. I’ve done that multiple times, tied a shoe. People think, Why? He can’t tie his own shoe? No. He’s got gloves on. He’s thinking about the next play. I just get it done, and he’s able to go back in.”

Sometimes a player might decide he wants his helmet visor removed midgame due to the heat in Miami—and then a dozen other players decide the same. Thiele stays calm as his massive hands undo tiny buckles or screws for players who want to hurry up to get back into a game. “Most guys wear visors,” he says. “Our guys will get used to [the heat] over time, but sometimes they go out there and say, ‘Hey, I want my visor off.’”

Not all equipment asks are game-related—players know they can come to Thiele for extra socks, sweats or popular team-issued items. Hey, that hoodie was great. Can I get another?

Thiele’s contributions to the team are not limited to the gear his players wear. He has one other crucial job that’s a bit of a claim to fame: He is the stand-in center who snaps the ball to quarterbacks during certain drills.

Thiele joined the team as an intern shortly after graduating in 1994, meaning the first quarterback to put a hand under his butt during an offseason practice session was none other than Dan Marino. There was just one problem: Thiele, a natural lefty, snapped it with the wrong hand.

“All I hear is, ‘What the . . . ’” as Thiele retells the story of his very first snap. He was worried Marino had broken a finger or something. Thiele says legendary special teams coach Mike Westhoff showed him how to snap it right-handed, a move he’s deployed for every Dolphins quarterback since.

His talents are put into play for seven-on-seven drills or when offensive linemen are otherwise occupied. This includes on the field during pregame warmups as receivers run through their routes. “And I know it’s very important,” Thiele says. “Listening to their cadence, because it means something. Because that’s where the play starts.” Though he is thankful he won’t be called upon in an actual game. “I don’t have to block a 350-pounder in front of me,” he says. “So that’s the good part.”

Thiele explains that almost every quarterback is different in the way he likes to receive the ball, including how hard and at which angle. He can trace a lineage of Miami QBs from Marino to Tua Tagovailoa, and current backups Mike White and Skylar Thompson. As Thiele describes getting accustomed to what makes each QB most comfortable, he repeats a maxim so many of his game-day coworkers across the Dolphins’ organization live by: “You just figure it out.”