Bill Belichick’s Unparalleled Legacy in New England

In March 2019, NFL owners invited guest speakers to their annual gathering of the powerful. Thus one of the world’s foremost authors and speakers on the ancient philosophy of stoicism ended up at a cocktail reception with league power brokers.

Ryan Holiday didn’t know Bill Belichick personally. He did know that coaches and executives from the New England Patriots, the franchise Belichick transformed into a modern dynasty when NFL dynasties were supposed to be like dinosaurs, had publicly embraced his work and its relevance in sports, something that had never happened before. He saw Belichick standing at a table, alone, emitting do-not-disturb vibes.

“At that point, he’s basically at the peak of his career,” Holiday says. “His reputation is … everything. And what struck me in that moment is he had no interest in this social event, of any kind. It was so obvious he had been, like, mandated to bake it in.”

Still, Holiday approached.

“Hey, Bill, you probably don’t remember me, but I wrote The Obstacle Is the Way and …”

Belichick pulled out his phone, opened a notes file and showed Holiday a list of thoughts he jotted down during Holiday’s talk. This turn was remarkable. For one, a coach who made Ticonderoga No. 2 pencils famous actually uses his notes folder. For another, Belichick had other notes on stoicism, even from Holiday’s newer and less well-known volume, Ego Is the Enemy. They spent the next half hour “nerding out” on Seneca, Marcus Aurelius and lacrosse.

“Here’s the greatest to ever do what he [has] done, and somehow he’s not comfortable being in a group of his peers,” Holiday says. “But as soon as something came up that fascinated him, he couldn’t have been more welcoming and excited.”

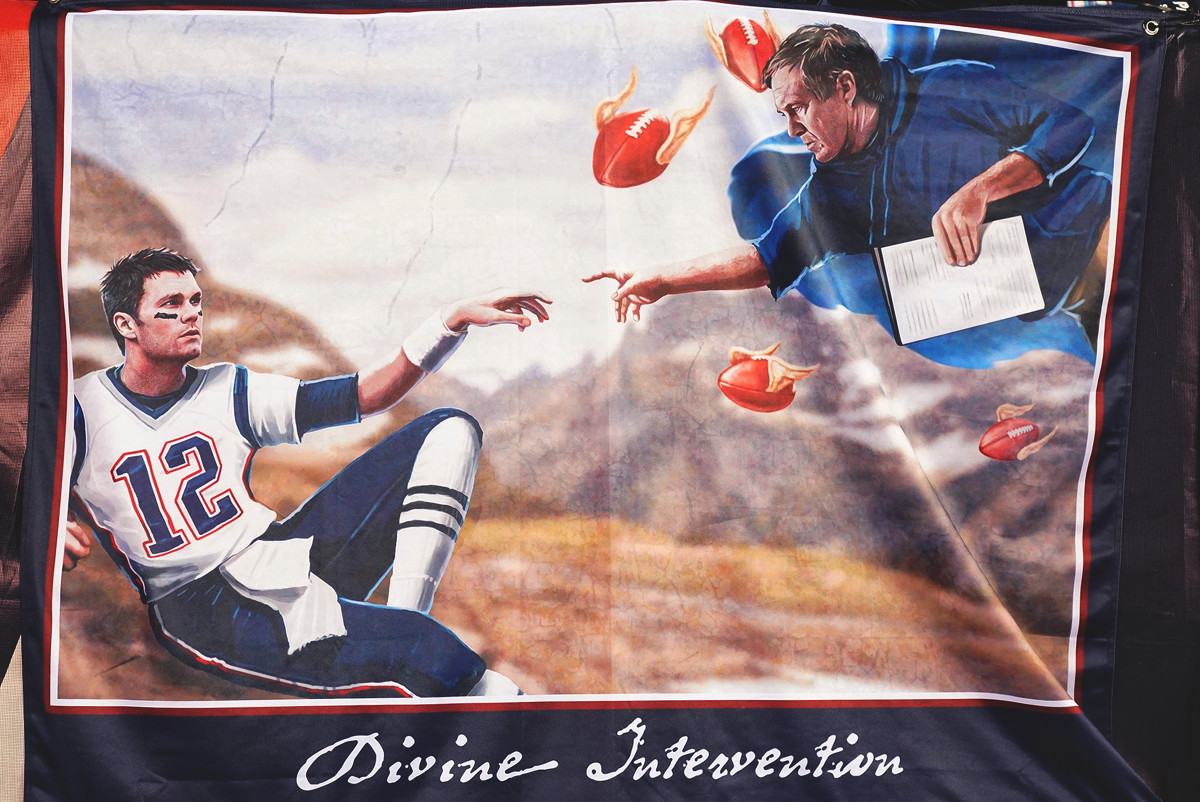

Besides dropping perhaps the first-ever mention of excitement in relation to one William Stephen Belichick, Holiday’s story illuminates a legacy as multifaceted as any in the sport’s history. Bill Belichick is far more than a brilliant coach—he is a winner of football games, collector of rings, schematic genius, creator of sports philosophy (“we’re on to Cincinnati,” “do your job”), mentor of Tom Brady and conductor of the most successful sports franchise this century.

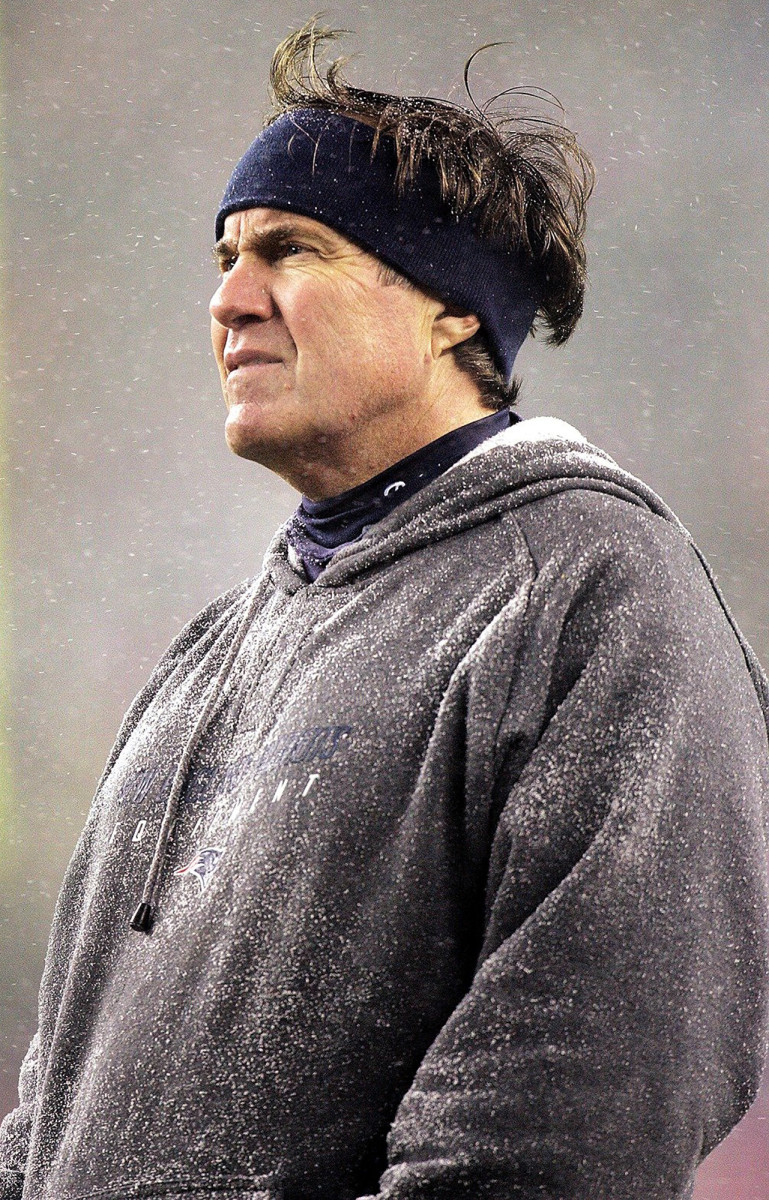

Belichick also changed football beyond just football. He championed castoffs and the importance of elements of the game few ever described as important (like special teams). He pushed counterintuitive, malleable strategies into vogue. He made cutthroat cool and yet remained more human than typically portrayed. He made fashion statements by frowning at style, with hooded sweatshirts snipped at the elbows and flip-flops worn to Super Bowl scrums. He taught leadership, strategy and the combination of both without trying to teach anything beyond football.

With Belichick set for a gridiron-shattering split with New England, whether he will retire or—gasp!—coach for another franchise, his legacy demands a thorough examination. But that legacy is as broad and multifaceted as any in the history of professional football, which required a similar approach. To fully assess the breadth of Belichick’s impact, Sports Illustrated spoke with more than a dozen people—some who know him intimately, others who are uniquely positioned to understand his place in sports history. They presented a detailed, nuanced picture of a man and his legacy: complex, idiosyncratic, Belichick-ian.

One thing became abundantly clear: For the thousands of cheap descriptions of Belichick as an emotionless, sleeve-slashing, player-releasing, tirade-unleashing cyborg, the coach might also be the most curious person in sports. Every other facet of his legacy starts there, with a bottomless, probing nature and the many, many ways in which Belichick applied it.

1. BELICHICK, HISTORIAN

The greatest coaching career in NFL history began in 1975. Belichick first toiled as a low-level assistant for the Baltimore Colts, a franchise soon to relocate (’83) to Indianapolis.

Having witnessed football history up close, for years and then decades, for nearly half a century, Belichick embraced football history, his constant, the foundation. He studied it, taught it, applied it, then … became it. He never deviated from that historian bearing, becoming part librarian in addition to all coach.

His father was also those, a football man and history buff. Steve Belichick played fullback for the Detroit Lions in 1941. The next year, he joined the Navy, never playing in the NFL again. He later worked at the U.S. Naval Academy, for its football program, primarily as a scout. He collected volumes of football history, more than four hundred books in total, and he raised young Bill in that environment, surrounded by the only textbooks he ever needed. His father wrote a tome called Football Scouting Methods, which became the Bible of that endeavor, the industry standard—and that piqued his son’s curiosity.

“He has such a huge reverence for the game, the people who taught [it] and the genesis of it,” says Dante Scarnecchia, who spent 34 seasons in New England, the majority with Belichick as his trusted offensive-line guru.

In mid-October, when New England inducted Scarnecchia into its hall of fame, Scar figured Belichick wouldn’t attend the celebration dinner, scheduled for the night before a Week 7 clash with Buffalo. Of course he knew how the Patriots’ latest campaign was going, which, for anyone who still lacks internet access, was: not well. New England’s record heading into that game stood at 1–5.

Not only did Belichick show up, but he stayed for dinner and regaled the head table with stories. Speaking at the induction ceremony, Belichick told one about how one year in training camp Scarnecchia blew a fuse at a mammoth offensive tackle who was ignoring his teachings. Scarnecchia recalls the setup, how “in my usual undiplomatic way,” he screamed while staring almost straight upward at a giant who seemed to double him in size. As Belichick spun through this yarn, he grew more animated, showcasing the side of himself he rarely reveals in public but often reveals elsewhere. He reenacted the full scene, showing how the tackle could have raised an arm, closed a fist and pounded Scar from the head, like a hammer would a nail, right into the ground. The room erupted in laughter.

“He was just special,” Scarnecchia says. “The outgoing, affable guy with a million stories. That has always been a part of him.”

No one, after all, ever made history without first embracing it.

2. BELICHICK, ORIGINATOR

Corey Dillon cackles over the phone, having anticipated the awkward question about the widespread and widely accepted notion that the Patriots under Belichick assumed risk that scared other franchises away from talented players with issues. The risk assumed varied as part of a sliding scale, related, always, to talent.

“Maaannnn,” Dillon says, pausing his cackle to quote Dr. Dre. “You know I started this gangster s---!”

He’s not wrong. Consider a partial list of talent rentals under Belichick: Albert Haynesworth, Randy Moss, Aqib Talib and Antonio Brown. Different issues, eras, assessments of risk vs. reward. All premised on the strength of the Patriot Way.

Dillon, per his own admission, arrived in 2004 with more baggage than a Louis Vuitton store: a surprise inactive (traffic accident), sideline outbursts, interview outbursts and, generally, a malcontent’s reputation. But he ranked among pro football’s top running backs, hence the price tag: a second-round draft choice for a player the Bengals no longer wanted.

Before the trade, Dillon flew to New England for a secret meeting so the two sides could feel each other out. He didn’t know what to expect, only that he would meet with Belichick and Scott Pioli, Belichick’s chief personnel executive. Dillon estimates the meeting lasted no longer than five minutes. “It was simple as hell, man,” he says. In his memory it went like this:

Belichick: Corey, I’ve heard about some of the situations that were going on in Cincinnati. Can you give me your thoughts on that?

Dillon: Coach, what does that stem from? That stems from not winning, man. I’m a competitor. My whole focus is going out there, winning games.

Belichick: O.K., I understand that. I get that.

Dillon stayed silent, waiting for the next question.

Belichick: Do you think you could play for us?

Dillon: Absolutely.

The conversation ended there. Soon after the trade was completed and Dillon arrived in Foxborough, he met with the Patriots’ offensive coordinator and Belichick disciple, Charlie Weis. “Hey, Corey, don’t get here and change, man,” Weis told him, per Dillon. “We want that Corey. The same Corey that’s been playing the last seven years. Don’t change a bit. Don’t feel like you have to come here and be somebody different.”

Dillon played three years in New England, picking up a Super Bowl ring in 2004 and retiring after ’06. Moss went to New England the following year. When they ran into each other years later, Dillon says Moss told him, “You paved the way.”

The most misunderstood aspect of New England’s approach might be this notion that it took in troubled players but expected to morph them into choir boys, fitting in through assimilation alone. But while the standard was the same for anyone, coaches didn’t want them to be anything other than what made them great to begin with. As long as a player like Dillon operated within the standard, then the best version of Dillon was the man himself. Proof: 51 total games played for New England, a pivotal role in at least two playoff wins (both from the 2004 season), a Pro Bowl nod (also ’04) and a Lombardi Trophy lifted overhead. Without him, New England doesn’t win its third Super Bowl in four seasons.

“You know what I’m proud of?” Dillon says. “I get to say, ‘Man, I helped Tom Brady win a f---ing Super Bowl. Are you kidding me? I’m part of that, the whole mystique. Bill Belichick and Tom Brady—I’m in that equation.”

He pauses. Then: “Maaannnn, that dude is … a genius.”

3. BELICHICK, ICON

John Conti won his first competitive eating contest in New Orleans, on Super Bowl weekend in 2002. He ate more than 400 oysters that day—and right before his home state football team captured its first title under Belichick. A pair of lengthy dynasties were born.

The eater known as Crazy Legs lived in Manhattan, where he frequented an East Village haunt, Professor Thom’s, known as a headquarters for transplanted Boston sports fans (slogan: “Behind Enemy Lines Since 2005”). On Sundays every fall, something like 1,000 chowderheads crowded inside, occupying every inch of two floors. Every time a Boston sports team did something significant, employees rang a bell. Conti, who would transition from regular to bartender, rang a lot of bells, until he began complaining of Bell Elbow. Thom’s closed during COVID-19, never to reopen, forcing a slogan change: to RIB, or Rest In Brady. Belichick’s run in New England outlasted Thom’s existence.

“Going to the Super Bowl is usually the rarest thing in a franchise’s history,” Conti says. “We could basically count on it like Thanksgiving.”

Belichick, the icon, by some numbers, a complete list far too long to compile in one place: 333 career wins (including playoffs), second-most ever, trailing only Don Shula and by only 14 victories; 49 years in coaching; 31 Patriots playoff victories; 29 seasons as an NFL head coach; 21 seasons as an HC above .500, 17 division titles; 13 AFC championship game appearances; nine Super Bowl appearances; and eight rings with six in New England (most ever) and two as a Giants assistant.

4. BELICHICK, OG SPORTS STOIC

The resonance of his work in sports surprises Holiday, even now. But, as has often happened over the last 49 years, Belichick saw value before anybody else, embracing the ancient philosophy before what seemed like every coach in every sport came to view Holiday as a beacon.

Holiday views Belichick as more lowercase stoic than uppercase Stoic, no disrespect intended, the difference owing to application of philosophy. The Stoics among us, Holiday says, know all the philosophers from ancient Greece and ancient Rome and rigidly follow their ideas from centuries ago. The stoics study the same stuff but follow the principles most applicable to them. Control what you can control. Ignore the rest. Do your job.

Belichick embraced and applied whatever happened in any one season—changes in league rules, schematic evolutions, player arrests, locker room revolts, scandals, injuries, staff departures, in-season trades—by lasering his focus on only what he could directly impact, breathing life into mantras like Do Your Job. But where Stoics believe in the concept of amor fati—to not only accept one’s fate, regardless, but to love it, also regardless—Belichick could accept but not always love. “This isn’t just a guy who’s all steak and no sizzle,” Holiday says. “This is a guy who has contempt for sizzle.”

And still: the OG sports stoic.

Holiday still has the email sent to him by a Belichick lieutenant, dated Oct. 1, 2014, that birthed their unlikely mind meld. He sees Belichick’s stoic superpower as “going to the essence of a situation, the objective facts of a situation … not really giving a s--- what other people think, what conventional wisdom is, being indifferent to anything that doesn’t matter.”

In sum: “He has this indifference that almost borders on contempt for the things that other people care about and obsess over.”

Indifference is an important word in stoicism, a bedrock to the overall approach.

Indifference didn’t always work for Belichick. He never underwent public image cleansing, never did what gruff coaches often do, becoming warmer and fuzzier and more relatable over time. He brushes off reporters for doing what he tells his players to do—their jobs—turning phrases like “we’re on to Cincinnati” into matador avoidance capes. This cemented his reputation as a surly, sometimes demeaning, overlord/cyborg. “That personality was required to be part of his generation of football coaches,” Holiday says. “It doesn’t necessarily translate well into a beloved, photogenic personality.”

Indifference may be the one word that perfectly explains Bill Belichick. Just ask Corey Dillon.

5. BELICHICK, MR. PREPARATION

On a September afternoon in 2001, Mike Westhoff coached in an NFL game of great significance. It was the first weekend the NFL returned to play after September 11 and, working then for the Jets, he knew emotions would be high. He wasn’t wrong, but what happened in that game carved the day into NFL history for another reason: Drew Bledsoe, Mo Lewis and a hit so hard it sent Bledsoe to the hospital and threatened his life. In came his beanpole backup, an unknown named Thomas Edward Brady. New England won, 10–3, and Westhoff asked his boss, Herm Edwards, a question being asked all over the country. Who is that skinny quarterback?

“He looked pretty good,” Westhoff says now. “And all of a sudden, the Brady era began to come alive.”

Cue the dramatic theme music, along with an impossible debate. The kind that can never be settled beyond always subjective (and often-biased) opinions. How to separate their legacies? Which force of football nature came first? Which GOAT most impacted the other’s GOAT-ness?

Bill Belichick Now Seeks a Job in an NFL That Has Changed

The majority of those SI spoke to believe a third answer works better than choosing between the two. All acknowledge that Brady won a seventh Super Bowl with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers after leaving New England. In nearly four seasons since his departure, the Patriots have gone 7–9, 10–7, 8–9 and 4–13—mediocrity personified until, this season, when New England hit bottom. To credit Brady with all or even the bulk of Belichick’s success is shortsighted. They accomplished what they accomplished together. Each made the other better. Yes, Belichick was fired in Cleveland (before Brady), after five seasons with one winning record. But he also shaped a defense as the Giants coordinator that ranks among the most feared in league history, that changed NFL history. His game plan to shut down the vaunted Bills offense in Super Bowl XXV famously resides in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. And for all his success in New England, it’s often overlooked that he led the Patriots’ defense, under Bill Parcells, to Super Bowl XXXI. Brady had zero to do with any of that.

Perhaps the best approach to this debate is no debate at all. Why parse, when it’s easier to credit, marvel at, or attempt to understand? “[Belichick] knows how to put a team together,” Westhoff says. “He certainly did, anyway. Tom Brady came along and accelerated his progress. But at the same time, early in, they were an exceptional defensive football team.”

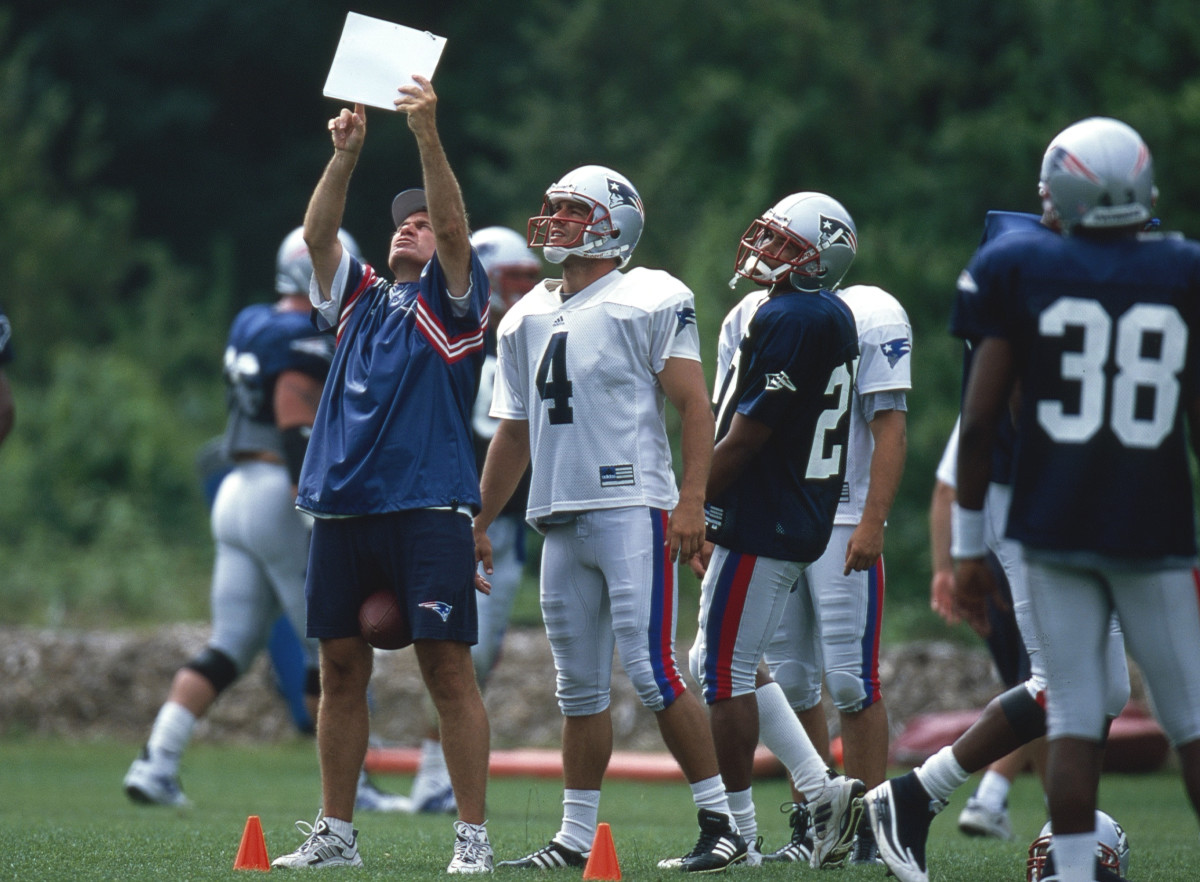

As for Belichick’s specific role in dynasty creation, Westhoff points to his mastery and thoroughness of preparation. Like Belichick, he’s a football/coaching lifer. Also like Belichick, Westhoff studies at maniacal levels, even after returning to the NFL this season to run special teams for Denver, at age 75.

Whenever Westhoff matched wits with Belichick, two of football’s most prominent special teams savants went head-to-head. When studying Belichick to prepare for these clashes, Westhoff saw a coach after his own clipboard. Belichick teams were consistent and prepared for every small tiny thing. They didn’t make many unforced errors. Those games inspired Westhoff, who believes Belichick assumed a more conservative approach against him specifically. He took that as a sign of mutual respect. “You had to beat them, go after them,” Westhoff says. “And that was never easy. Never.”

6. BELICHICK, LEADER

Stedman Graham, author, speaker and educator, specializes in leadership. As a consultant, his approach has been implemented all over. As Oprah’s longtime partner, he witnessed another approach, hers, up close. All informed his preferred style of organizational guidance—for anybody, including coaches: identity leadership.

This approach starts with leading self, a Belichick staple trait—the idea that you can not lead others until you lead yourself. One trick Belichick always managed to pull off was maintaining his overall system and philosophy—the so-called Patriot Way—but finding new ways to adapt within it. Sometimes, adaptation came from schematics; others, through player transactions or coaching changes. The Patriots always made it work, even when Brady tore his left ACL and MCL in 2008. Belichick swapped in Matt Cassel and went 11–5 (even though they missed the playoffs).

There are stoics all over now, from Mike McDaniel to Sean McVay to many others. But they also come from a different generation and have a different approach with younger players. “Leadership,” Graham says, “is very different today than it used to be.” Gone is the blanket acceptance of Do Your Job types who give instructions and expect them to be followed without exceptions. That has been at least partially replaced by deeper understanding between bosses and employees, cooperative strategies and more holistic views of how to best prepare football players/teams. “It’s very difficult to lead today,” Graham says, “because we’re leading from the old lens, which is more difficult today than ever.”

7. BELICHICK, DYNASTY BUILDER

One source floated an interesting notion. Would Belichick fit as the silhouette or image for a new NFL logo? Hence a call placed with Jerry West, The Logo, part of not just NBA history but the league’s branding. When reached by phone, West swatted the idea away like Dikembe Mutombo once slapped wayward shot attempts into bleachers. “Oh, my God … I don’t even … that’s just all [the NFL] needs,” West says.

Fair enough. West understands both the creation of dynasties and what must be undertaken to sustain them. He saw this, up close, from every vantage point (Hall of Fame player, coach, Hall of Fame–caliber executive), with more than one franchise.

One experience, from 1991, seems particularly relevant. The Los Angeles Lakers were attempting to win their first title in four seasons when they lost Magic Johnson that November. This isn’t an exact comparison to Brady’s fleeing New England—Johnson’s reason for retiring, a positive test for HIV, was far more serious and important than basketball. West isn’t making an exact comparison. He’s saying that, in the event of a catastrophic injury or the departure of a generational talent, moving forward for any dynasty borders impossible.

“You’re saying to yourself, Oh, my God, how are we going to survive?” West says. “Earvin kept everyone’s spirits high, because of his personality. His ability to dictate was second to none. Not only that, he was someone I loved—love. Forget about basketball. He was a human being and that pushed me back to reality.” He pauses briefly, then adds, “It’s hard to even think about.”

A Complete Timeline of Bill Belichick’s Patriots Career

As the person in charge of shaping the Lakers’ roster, Johnson or no Johnson, West also understood an impenetrable baseline. Diehards still expected the Lakers to win—a sentiment that’s applicable to Belichick right now, as if the previous two decades aren’t enough to buy him a touch more grace. The majority of the unforgiving don’t know what it takes to build a dynasty, let alone maintain one. The Lakers didn’t win another championship until Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant came to town. Even then, Shaq and Kobe showed teams everywhere the difficulty in maintaining dominance. They feuded. Won three rings. Broke up.

“That [Belichick] is also the personnel director doesn’t help,” West says. “When things are rolling, everyone thinks you’re the greatest. When they’re not, you can’t do anything.”

The primary emphasis never changes. In sports, it’s win. An NFL team that cannot score cannot win. Does that erase the 300-plus victories that came before this season? No. Does it tinge Belichick’s legacy? Still no. What about when combined with the brutal stretch in Cleveland? Come on! All answers point to the same conclusion: Bill Belichick created a dynasty in a league and during a time period when that wasn’t thought to be possible anymore.

8. BELICHICK, DEFIER

Jimmy Johnson, retired football coach and dynastic architect turned broadcaster, opens an interview with his conclusion. “The greatest coach of all-time,” Johnson says.

Other coaches have won more games, fashioned dynasties and transcended sports. But no other NFL coach did what Belichick has this century. He built a dynasty with Super Bowl runs at both ends, sandwiched around a decade-long, no-title gap when New England still played in championship games, losing two by margins thinner than the shell of David Tyree’s helmet and the blades of turf between Mario Manningham’s toes and the sideline. He still won (games, division titles, hatred) at an astonishing clip.

For Johnson, what separates Belichick from other deserving, accomplished, Mount Rushmore–type coaches, is that, the time period he dominated. Bill Walsh, Chuck Noll, Tom Landry, Bill Parcells, Vince Lombardi, Joe Gibbs, Paul Brown—or anyone else from before the NFL introduced free agency in 1993—built talented rosters that were, for the most part, kept intact for the entirety of respective runs. That applies to Johnson, who coached the Cowboys during their mid-1990s Lombardi Trophy–collecting stage. (A modern counterpart, like Andy Reid, would also qualify. But in the same league, under the same conditions, he has netted “only” two Super Bowl trophies to Belichick’s six.)

That’s the thing with Belichick and legacy. He triumphed more than anybody—only Shula holds more actual wins, but Belichick won four more Super Bowls. He won like that in an era when nobody wins like that. Anyone discounting his accomplishments by invoking Brady’s impact might want to check the rest of the list, Johnson says. Each coach on it had superstars, multiple, maybe not of Brady’s caliber but also probably more in any season than Belichick ever had in New England. The pairings were the point.

So while Johnson credits Belichick for innovations, like being one of the first coaches to adjust offensive and defensive gameplans every week, he also argues for era as the separator. He points to the numerous assistants who left New England, became head coaches and stumbled/bumbled/tumbled into oblivion. Others deploy that notion as criticism, a lack of coaching talent produced by Belichick, the NFL’s saddest, shortest tree. Johnson doesn’t see it that way. The assistants didn’t succeed, he says, because they weren’t Belichick. Which … “Again, that’s a testament to how great he is,” Johnson says. “Head and shoulders above everybody else. Nobody can match him.”

It is widely believed that Belichick thinks deeply about his place in football history. Scarnecchia insists that he does not believe that the game’s foremost active historian has considered his legacy too deeply. He views that similarly to the Patriot Way, a phrase he never once heard among the staff, let alone from Belichick himself. “Honestly, I don’t know,” he says. “He’s so involved in the moment, I’m not sure he’s worried a whole lot about … what his place will be. Maybe his mind does wander there, but I just don’t see that with him. He’ll just let that happen as it happens.” Scar also wonders whether his old boss will truly leave the game behind. “I’m already interested in how far he steps away, if he doesn’t hang on around the fringes; we’ll see.”

Even Dillon, the famously punishing running back, gets sentimental, thinking about The End for Belichick, whether after this season or next season or any other upcoming season. “I don’t think football will look the same without that guy around,” Dillon says. “It’s kind of heartbreaking. Best coach. NFL history. Hands down. I don’t know how to feel about that, man.”

9. BELICHICK, GREATEST

In a career that began in 1974, Westhoff, the former Jets special teams coach, spent more time in Miami, as part of the Dolphins’ staff, than anywhere else. This made him a Don Shula disciple, for life. Before Shula died in 2020, the iconic coach made no secret of how he believed his legacy compared to Belichick’s. He was especially critical of the “gates” Belichick confronted over the years, whether of the videotaping or deflating variety. When asked something about Belichick by the Sun Sentinel in 2015, Shula responded, “Beli-cheat?”

The majority of NFL insiders, coaches, analysts, players and executives SI spoke to say they saw the gates as significant but minorly related to Belichick’s legacy. They pointed to how rules and boundaries are often pushed across the league, with “creative solutions” to new problems often stirred up, what Westhoff calls “the stuff that’s a little bit off-color.” He also has been critical of Belichick. But when asked how much the scandals should matter now, or moving forward, whenever Belichick retires, Westhoff says he never believed that Belichick won football games with shenanigans.

Johnson agrees with that sentiment, even more strongly. “People were [filming opponent’s signals] 10 years before any of that came out,” he says. “I did it myself. I picked it up from Kansas City. They told me they were doing it 10 years before Belichick ever did.”

Are people, then, trying to find warts to assign Belichick and his résumé? “They did the same thing at the University of Miami,” Johnson says of his time coaching the Hurricanes. “Everybody wanted to knock us down.”

Westhoff says, “I’m a big Don Shula guy. And when I worked for him, he wasn’t just the head coach of the Miami Dolphins. He was the head coach of the National Football League.” Belichick is like that, the latest iteration. “You can’t take away what he did,” Westhoff says.

10. BELICHICK, LASTING IMPACT

After the season in which Cassel helped Belichick prove his genius, Belichick traded him to Kansas City ahead of Brady’s return. Cassel played in the NFL for as long as he could, bouncing among seven franchises before retiring after 2018. At each stop, and as he pivoted away from football, into real life, family, retirement and, now, broadcasting, he heard the same voice.

Cassel hears Belichick when he studies game film for upcoming assignments. Cassel hears Belichick coming out of his own voice when teaching something to his children. The attention to detail, the focus. He hopes he’s a teacher like Belichick and wants to impact those around him similarly.

The difference between how Belichick operated and other coaches’ approaches was obvious to Cassel right after he left. He grew up in the Way, spending his first four seasons with Brady and Belichick. Other teams didn’t practice situational awareness related to extreme or poor weather—in March. They didn’t run two-minute drills—at the beginning of OTAs. Other coaches didn’t drop by during practice with the most granular of details, something like how a certain cornerback played a wheel route the same way, always backing off, in late-game situations. Belichick would always have a counter-maneuver in mind. When players saw what he told them, in one game or another, lo and behold, Belichick was right exponentially more than he was wrong.

After leaving, Cassel found himself in other meeting rooms laying out Belichick’s philosophy and counters without trying to. Those systems weren’t as regimented; those teams, not as locked in. Those coaches could still coach. They just didn’t coach like Belichick. “You realize and have an appreciation for that level of attention to detail,” Cassel says. “You appreciate it so much more, because you understand the other side.”

Cassel shakes his head at all the people looking to bury Belichick after the Patriots’ recent struggles. “It’s fascinating how quickly (people) forget about his 20-year reign atop the NFL, the gold standard,” Cassel says. “There’s no patience. The guy’s been at the top of his profession for almost 40 years. There’s respect that this man deserves, and his body of work speaks for itself.”

Cassel wishes others could have sat in a Friday quarterbacks meeting, where Belichick would stumble in and begin another history lesson. Did they know that receivers, back in the day, used to line up like linemen, hands planted in dirt? Why did someone decide to stand them up? Why did someone else decide to spread them wider and wider across the width of fields? Sometimes, he added old game film to these lessons; others, he’d show pictures; still others, he'd rise from a chair and demonstrate. Cassel watched him teach and never left the room anything but awestruck. Belichick would throw on film of Lawrence Taylor and explain what made him exceptional, such a force that offenses had to change entire schemes to account for him.

Teaching wraps so many other disparate legacy elements together. It helped players understand schemes and why he changed them. Gave them an appreciation—ideally, that netted motivation—for their craft. Made them better football players. Indoctrinated them into the Way. Made them smarter, more rounded. When Cassel calls Belichick “the greatest coach in NFL history, no question,” he starts there.

11. BELICHICK, LEGACY

The final interview for this story took place in late December. Appropriately, on the week before Christmas, a gift was involved. It came wrapped in the form of an early-morning phone call from Mike Krzyzewski, one of few humans on earth who can understand what it’s like to be Bill Belichick, to carve not just a dynasty, but an ethos that will thrive/sustain/be remembered long after retirement.

In short, when it comes to Belichick, Krzyzewski gets it in a way few people could.

On sustaining excellence that’s not supposed to be sustainable: “You have to understand: There’s going to be intense preparation. Wanting to do it and preparing to do it, like I did, like he does, again and again, they’re not the same.”

On the drive summoned over and over: “Being worthy of accomplishment means you paid a price to achieve it. It takes a lot. You have to sacrifice. You have great focus. Bill did those things. They’re what separated him.”

On culture/ethos/way(s): “You have to keep working at culture. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an exact definition of the Patriot Way, but whatever I have studied, I’ve been in awe of. It’s based on everyone owning it, feeling a part of it, those values and standards becoming a part of them.”

On coaches, the best coaches, as teachers: “That’s what we are. Teachers. That’s Bill. That’s him.”

On understanding history to become part of it: “A must. Being at the Naval Academy helped him go even deeper into character and be around people who embodied it. This matters.”

As the interview winds to an end, Krzyzewski lands in the same place that Holiday began. The stoic author and the beloved basketball coach see Belichick’s superpower the same way. He’s simply… curious. Intrinsically. Deeply. Unflinchingly.

Hence why the legacy of Bill Belichick, NFL curmudgeon, teacher and mentor, student and philosopher, stoic and special teams savant can be easily summarized: unparalleled.