Dave Canales’s Journey From Cowboy Boot Salesman to NFL Head Coach

Dave Canales sat on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean in San Pedro, Calif. His wife, Lizzy, was by his side, seven months pregnant. They packed sandwiches and the day was clear enough to see Catalina Island off the coast. It was 2009, and the Canaleses’ coaching dreams felt somewhat uncertain. The couple took a moment to reflect.

Pete Carroll, who had given Canales a low-level job the year before at USC had taken off to coach the Seattle Seahawks. Canales raced with thoughts about what he’d have to do to survive a regime change under new head coach Lane Kiffin, amid the cutthroat lower rungs of a big-time program.

The silver lining of trying to stay with the Trojans was that he could remain anchored to his family nearby and the church his grandfather founded, Mission Ebenezer. There, Dave coordinated the music. Dad, Isaac, was the pastor. Mom, Ritha, was (and still is) an assistant pastor and director of the welcome team. Older brother Josh was primed to take over. Younger brother Coba would be a pastor there, too.

Just a year before, Canales was the special teams and tight ends coach for El Camino College. Two years before that, the offensive coordinator for Carson High School. Two years before that, he was running a start-up business selling Rudy Lara cowboy boots, humping a supply to trade shows across the United States and venturing down to Mexico to give input on popular styles. A family friend had given him the job right out of college, never even having seen him wear the things. The friend just assumed that, after seeing Canales around the church, he could handle inventory, packaging, selling and ordering. He was right.

Back on the cliff, Dave and Lizzy joined hands and prayed for guidance. Maybe they could stay in California and deepen the lives that they had started to build. Canales had a standing offer to work in commercial real estate if coaching didn’t work out. He could make a lot of money and put the swimming pool in his parents’ backyard that they had always dreamed of (this was a running family joke, seeing as Josh was a professional baseball player at one point, and Dave could have been a business titan, and someone could buy them a pool). Lizzy had always done whatever it took, serving as the family’s breadwinner coaching cheerleaders at El Camino while Dave applied for limited-earnings positions or graduate assistant jobs. That would never change.

Or, he could simply double-down on what he felt he was born to do. Canales’s mother remembered him at age 5 holding a pink, see-through clipboard in their small living room, setting up a team of siblings and friends, ordering them around. Once, when Canales was 10, the head coach of his flag football team was late to the game, and Ritha had to take the whistle. She told her son to figure it out, and for 20 minutes, Davey ran the show, no problem.

After they had finished praying, they opened their eyes. About a hundred feet away, a bird had swooped in off the coastline and perched on a nearby tree. Dave crept close to take a picture with his flip phone.

It was an osprey. Nickname: the sea hawk. Point taken. Canales, those who know him say, was overwhelmed by a feeling of peace. Two weeks later, Carroll called Canales from the Senior Bowl and offered him a job in the NFL.

“God had his hand on Davey all the time,” says Rudy Lara, the friend who hired Canales to run his cowboy boot business. “It was evident.”

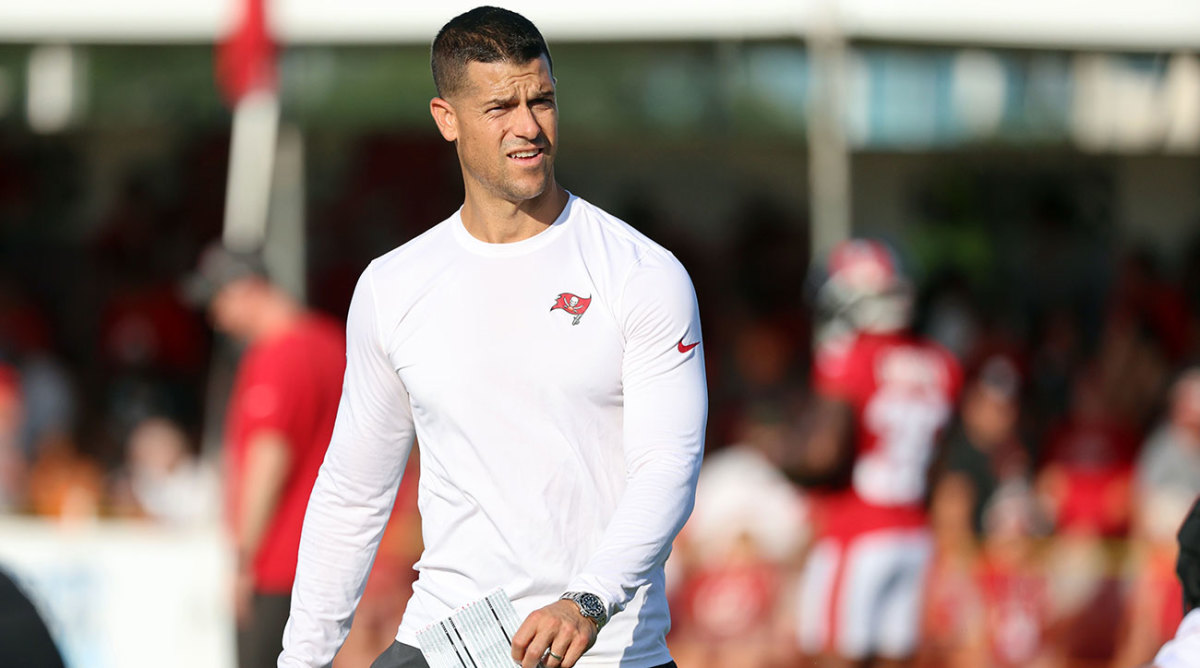

Last Monday, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers defeated the Philadelphia Eagles in the wild-card round of the NFL playoffs, Canales called plays for one of the most surprising units in football. The Buccaneers lost in the divisional round to the Lions on Sunday, but none of that matters now after the Panthers hired the former Buccaneers OC as their next head coach Thursday. Canales, who is Mexican American, is now the lone head coach in the NFL of Hispanic descent, continuing a small but proud fraternity that has included Tom Flores and Ron Rivera.

Before the season, the Tampa Bay job was one that a handful of more-tenured coaches and coordinators turned down, scared away by the prospect of having to run an offense through Baker Mayfield or Kyle Trask, and replacing the aura of the greatest player in NFL history, Tom Brady.

Canales rose through Seattle’s receivers room alongside some of the team’s best at the position, such as Doug Baldwin, Jermaine Kearse and Tyler Lockett. He became the quarterbacks coach for two straight Russell Wilson Pro Bowl years, the passing-game coordinator during what was arguably Wilson’s best season, and the quarterbacks coach again when Geno Smith won Comeback Player of the Year in 2022. Now, Mayfield is piloting an offense that finished the regular season fifth in passing touchdowns, 10th in net yards per attempt and is one of the best big-play outfits in the league. He is also a candidate for Comeback Player of the Year.

The rest of the football world is just now starting to figure out what the Canales family, steeped in the art of the miracle, already knows: There is no stopping answered prayers.

Watch Canales’s film in Tampa Bay, and it’s evident that he was willing to see the good in what remained of a post-Brady Buccaneers’ roster.

Mayfield could always rip a football, hitting deep out-breaking routes better than most passers in the NFL. Mike Evans and Chris Godwin were incredibly experienced and cerebral. Harold Goodwin, the run-game coordinator and assistant head coach, had the ability to create a running game that suited Rachaad White out of the shotgun while featuring an athletic offensive line, and marry that to a quick passing game that Tampa Bay had installed to manufacture touches for their best receivers. Gone was a lot of the duo-based running game that the Buccaneers had featured during their Super Bowl run.

In the scheme there seems to be flavors of Dallas and Brian Schottenheimer, Minnesota and Kevin O’Connell, Seattle and Shane Waldron, Green Bay and Matt LaFleur, and Cincinnati and Zac Taylor. But the personal touch appears to come in the way Canales sets up a defense for failure. Evans and Godwin can run any route available, and, because of that, they have run almost every variation out of every personnel setup, forcing defensive backs to hesitate at the moment when a receiver will commit to one direction. It’s a philosophy that is more commonly used out of necessity by teams that don’t have players like Evans, who could win on most routes. Canales, like Ben Johnson in Detroit, has taken that theory and applied it to more elite playmakers.

A few weeks back, in a game where the Buccaneers dominated the Jaguars on Christmas Eve, Evans was getting into his routes like a slashing guard approaches the paint, dribbling with eyes ahead, moving defenders mentally first. Evans looks confident because each route begins with an identical preamble, placing the defender into a situation similar to a goalkeeper during a penalty kick, forced to make an educated guess and hope for the best.

On a touchdown right before the half, Evans was lined up wide to the left. There was less than a minute remaining, so the Jaguars were protecting the sideline. Evans started chugging up the field blanketed by two defenders, one preventing him from breaking toward the sideline, running a route he and Mayfield seem to hit unconsciously with regularity, and one buffering him from breaking toward the middle of the field. Canales’s call had tight end Cade Otton, also on the left side, running a much slower-developing, out-breaking route. The break in Otton’s route synced up perfectly with a decision point in Evans’s route as to whether he would muscle to the sideline, break in, stop and turn, or keep going vertically. The Jaguars’ defender protecting Evans from breaking inward darted toward the wide-open Otton, vacating the middle of the field entirely. Now, all that remained covering one of the best receivers in football was one defender shielding the sideline.

Mayfield saw it instantaneously and whipped a knockout blow touchdown pass that put the Buccaneers ahead by 20 points at halftime.

Mike Evans passes Tyreek Hill for most receiving touchdowns (13) on the season!

— FOX Sports: NFL (@NFLonFOX) December 24, 2023

(via @NFL)

pic.twitter.com/1dmCpuVapg

It’s also evident that Canales simply has a knack for executing some perfect deep shots in critical situations, a reason why the Buccaneers are seventh in the NFL 20-plus-yard plays, behind only the 49ers, Vikings, Cowboys, Texans, Lions and Rams (the Buccaneers finished the season with one more 20-yard play than the Dolphins, often a team used as a kind of offensive barometer, and tied with the Dolphins in 40-plus-yard plays).

Against Minnesota in the season opener, the Vikings threw a screwball at the Buccaneers before halftime, sticking Harrison Smith in the middle of the field and inverting their Cover 2 defense.

Evans, who lined up wide to the right, was forced inside by the first defensive back he came across. As he was passed upfield and into the next layer of Minnesota’s zone, Evans began to execute what appeared to be a corner-post route. Evans leaned to his right, looking a bit like a trick motorcycle that was about to tilt over. Camryn Bynum, the Vikings defender, froze, uncertain whether Evans was going to take him to the corner of the end zone or toward the middle of the field, which, by now, Smith had long vacated, pressing himself up toward the line of scrimmage.

It was already over. Evans sliced toward the middle of the field, Bynum tried to switch his feet and by the time he could give proper chase, Evans was yards ahead, more wide open than a receiver of his caliber should ever be.

Baker Mayfield to Mike Evans for the 28-yard TD!

— NFL (@NFL) September 10, 2023

📺: #TBvsMIN on CBS

📱: Stream on #NFLPlus https://t.co/G4uoYVOqQn pic.twitter.com/z5ILOb4mlf

This is from the holster of a first-year play-caller, utilizing a quarterback who has been discarded by three NFL franchises already, behind an offensive line that, according to ESPN analytics, ranked 25th in pass-block win rate, and 31st in run-block win rate a season ago. While there is no doubt that Canales has talented receivers at his disposal, his rise from career member of Seattle’s coaching staff (2010 to ’22) to elite offensive coordinator at age 42 is nothing short of stunning.

That is, until you get to know the Canales family.

The abridged version of the Canales legend goes something like this:

Dave’s grandparents on his father’s side, Miguel and Lupe, came from Mexico. His grandfather served under general George Patton in World War II, among the first wave of landing ships to reach North Africa, having accepted a life of faith before his departure. Family members found him years later in an old National Geographic atlas of war material kneeling for Sunday service, the only Mexican in the photo, and the only one insisting on wearing a tie to church. He was wounded in battle and promised God that he would start a church if he could just get home safely. So was born the Mission of Ebenezer in 1959, with 15 parishioners in a series of buildings that included an old bar.

Dave’s father, Isaac, who had polio at a young age, rebelled from the faith at first. He spent his teenage years experimenting with psychedelics and playing the trumpet in clubs around town. During a trip that brought on some serious distress, he went home at 3 a.m. and asked Miguel whether there was any hope. Miguel, whom Isaac remembers looking a bit like Yoda at the time, told him that “hope was Christ.” The next morning, Isaac started following his dad around “like a puppy dog” asking him the questions that would soon formulate his path. He felt a succinct lightness for months that wouldn’t cease (oddly, the same feeling family ascribed to Dave when he saw the osprey). First came a religious community college. Then, Harvard for divinity school. Then a trip back home with his wife, and Canales’s mother, Ritha, to Mission Ebenezer.

“We’d drive an old beat-up van around the local city of San Pedro, Compton, Wilmington and pick up people to come to Sunday church,” Isaac said. “We had several iterations of those vehicles. An old Chevette, an old station wagon, another van with no seat belts.”

Isaac said he wanted to be the “Mexican Billy Graham,” but wound up instead turning the little old church into an institution with more than 3,000 members and services in English and Spanish (Miguel once said: “Why would we say a mass in English, when we’ll speak Spanish in heaven?”). Dave’s brother, Josh, who spent time in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ organization, eventually took the reins as the church’s lead pastor.

Isaac likes to say that “God got in the middle of it” when assessing the otherwise inexplicable moments of joy and grace in the family’s life. He tells stories of miracles both small and large, with Ritha loyally by his side, ensuring the details are correct.

A minor miracle (relatively speaking): Ritha was pregnant with Dave, and the family was living in a tiny one-bedroom, half-bathroom house. When she would come home from her job as a nurse, red-cheeked from exhaustion, she would roll the old Chevelle up the pothole-ridden driveway, the car swaying like a boat in turbulent waters. The two joined hands together and prayed for a new driveway. A month later, while Isaac was studying in the house, a pair of work crews showed up on either side of the Canales property. On one side, township workers helping to fit a home for handicap accessibility. On the other side, gas company workers showing up to repair a water main break. One crew had an excess of hot asphalt. One crew had an excess of fill dirt. Neither wanted to haul it all back home. Both saw what a mess the 50-foot pathway into the Canales home was. By the time Ritha came home from work, she had a beautiful new driveway.

“I asked him, who did you con into doing this?” she says now, laughing.

Isaac responded: “The Lord!”

A major miracle: When the Mission of Ebenezer moved to its current location, it sat on the same property as an abandoned warehouse formerly utilized by REI, an outdoors retail company. The Canales kids had always dreamed of transforming the space into a place where children could play sports. Josh had built a crude batting cage in the back and a decaying heavy bag was also hung there so that a local bantamweight could practice and stay out of gang life (he hit it so hard the stuffing fell out and was replaced with hay). The bantamweight went on to win a boxing tournament in California attended by Michael King, the owner of one of the most successful television production companies in the medium’s history (King World had put The Oprah Winfrey Show into syndication). King became enamored with the boxer, took a Learjet and a limousine to the church to see where the kid trained, and, upon walking into the building, felt the easing of a massive headache. One conversation led to another, and King said to Isaac: What do you think it will cost to get this place to where you want it?

Isaac, knowing little about construction or commercial real estate made up a number: $1.25 million. Over time, he estimates, more than $2.25 million has been put into the warehouse renovation. At a grand opening party attended by boxing royalty such as Evander Holyfield and Sugar Ray Leonard, there were Hollywood actors and power broker attorneys. Dave wore a nice suit and bumped into another friend of the King family who just happened to stop by: Carroll, then the head coach at USC. They named the gym The Rock because Ebenezer, in Hebrew, means “the rock of my help.”

Canales had been helping Carroll out at the coach’s summer camps. After that meeting, family members and friends would randomly run into the coach around town, reminding them that they were with Davey. Soon, he’d be on Carroll’s staff with the Trojans. Then in the NFL. There was a wind at his back that never stopped.

“It’s love and faith and supreme confidence that you draw from family and friends, from a good foundation of faith,” Isaac said.

Only the Canales family knows what happens next; only they know the contents of their prayers and the possibilities when faith has no outer limits. (Ritha and Isaac put in their own pool, by the way). Isaac likes to say that through faith lies freedom, and taught his kids as much all their lives. It is the freedom to believe—to know, somewhere deep down—that an osprey flying over the cliff is more than just a bird passing on through.

Editors’ note, Jan. 25, 1:08 p.m. ET: This story has been updated as the Panthers hired Canales.