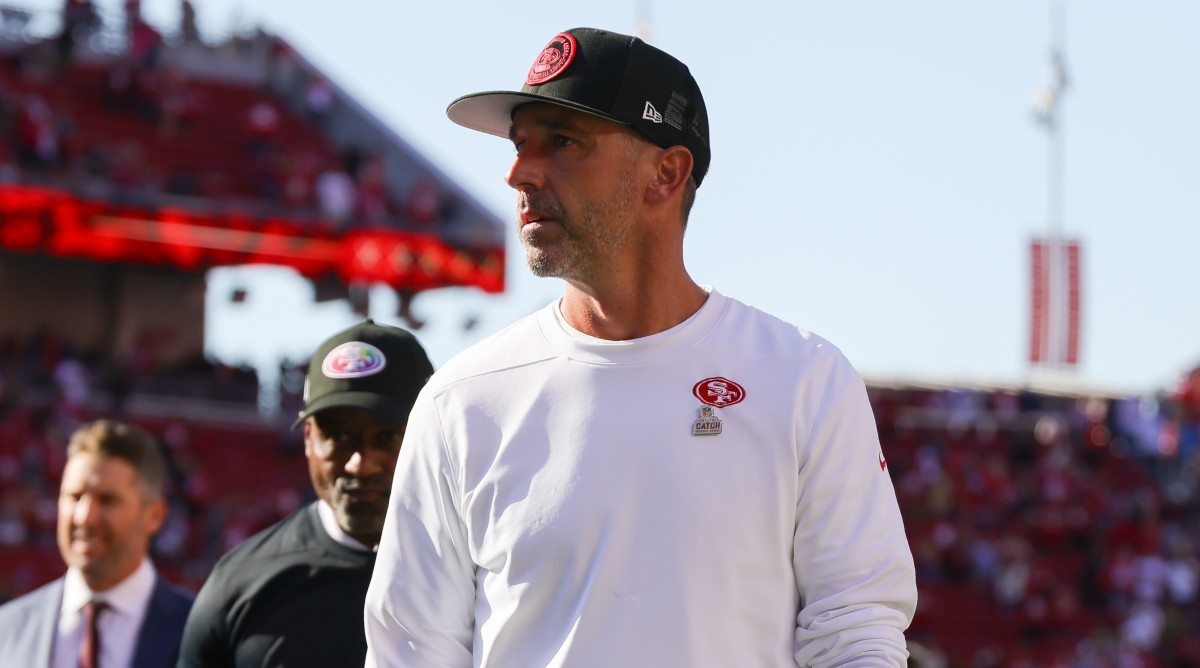

Super Bowl LVIII Newsletter: Kyle Shanahan’s Brilliance Is in the Details

Of all common coach archetypes, Kyle Shanahan best fits under the heading of “architect.” That concept applies to his role in roster construction, schematic designs and quarterback development. It starts in the obvious place, with his offense and all the myriad variations from assistants who took over other teams or Shanahan himself. He’s adaptable as a play designer; methodical, too; not to mention innovative and brilliant but also sometimes an over-thinker, too analytical, not enough in what’s called or like flow.

No need for that to cloud the overall narrative, though. Every team in the NFL would hire a coach with a brain like Shanahan’s and the playbook he lugs into town. After his first meeting with the San Francisco 49ers coach during free agency in 2018, cornerback Richard Sherman told anyone who would listen he had just found the “smartest football brain I’ve ever met.”

Sherman played for coaches with long track records, like Pete Carroll. “But the creative way that Kyle thought of each individual on defense and the way he could manipulate on any given play was something I had not heard from anybody,” Sherman says. “It’s one thing to say, we can manipulate a scheme. But to manipulate players on one play is just like … another level.”

Shanahan is many things. Relatable enough that his players address him as “Kyle” rather than the more typical “Coach.” Thorough enough—or paranoid enough—to outfit his position meeting rooms with cameras, so he can monitor coaches and their interactions with their players. Fashionable enough to wear Yeezys on the practice field. But the main reason the 49ers turned their franchise around quicker than anyone expected is his brain and the precise, calculated approach he takes to offensive football. His offense is at once grounded in simplicity and yet infinitely complex.

The score-score-and-score-some-more philosophy starts with central tenets: collect fast, athletic players and create space for them to operate; run the ball to assert dominance; control the clock; adjust constantly; keep defenses off balance, thus opening more space. He loves to run the outside zone. He majors in play-action passes. He wants to make those concepts look similar, then changes which players go where and how wide they split out.

Super Bowl LVIII Newsletter: Dissecting the Brock Purdy System QB Debate

He also knows specifically the traits he prefers in players at each position. Take offensive linemen, for instance. Shanahan wants lighter ones who are more athletic, because he asks them to move laterally more than most coaches. When he became the Atlanta Falcons offensive coordinator in 2015, he cut every lineman who didn’t fit that prototype. Only two did. None fit this Shanahan-specific mold better than Trent Williams, the rare offensive tackle with so much athleticism he could also play on the defensive line. Hence why Williams remains a 49ers cornerstone, having played for Shanahan in Washington, before reuniting in SF in 2020.

Or running backs. Shanahan was always enamored with Michael Bennett, a speedy, shifty ballcarrier who could catch passes and hit holes for long gains in Tampa. When Shanahan took over in San Francisco, he resolved to find similar players—only faster, so that they could speed through the space he intended to create. Instead of signing one back like that, he found four, each with sub-4.4 speed in the 40-yard dash, the NFL’s closest thing to a 4X100 Olympic relay team. “There are probably 10 of those guys in the league,” Mike McDaniel, the former 49ers assistant and current Miami Dolphins head coach, told Sports Illustrated in 2019. “And we have four of them.”

From there, Shanahan creates a menu of plays with endless variations; the same bunch formation yields dozens of options, based on which players stand where in the bunch and what their strengths are compared to the weaknesses of individual defenders, which will dictate which routes they run or how they block. Each element is incredibly specific. The overall menu doesn’t change a ton over the course of a season, but Shanahan’s choices for any given week vary greatly. Players say they do roughly 60% of play installations each week. Even in games, there are options, ways to counter counters from opposing coordinators. On most plays, Shanahan gives quarterbacks two options. They get to the line, assess the defense and choose between them.

Super Bowl LVIII Newsletter: It’s Fathers and Sons Week in Las Vegas

Many who played for Shanahan note that he can be uncomfortable speaking in front of teams. He often appears nervous, anxiety oozing from underneath his wide-brimmed baseball caps. But not when he’s teaching offensive football; or football, period. In those moments, Shanahan is at his most clear and most concise. One confidant, who didn’t want to be skewered for the comparison, says Shanahan reminds him of Bill Walsh that way. Smart. Innovative. Narrowly focused. Which also recalls, well, his dad—two-time Super Bowl champion Mike Shanahan.

This variance, the constant tweaking and adjustments, are where the complexity in Shanahan’s system lies. Defenders hate going up against this touchdown machine he built, even in practice. Dee Ford told SI in 2020 that Shanahan offenses blend physicality with intricate design concepts more than any other in the NFL. Practice hurt, then, in mental and physical senses. “Man, Kyle takes so much s---,” Ford concluded then. “What else can the man do?”

Then to now

Details in the origin story of how the Super Bowl came to be named have varied over time. But what’s not generally disputed is this: Part of that story originated with a toy Lamar Hunt’s children—including Clark, who was 10 months old at the time—enjoyed. Super Ball, the toy was called. Made by the Bettis Rubber Company, starting in the mid-1960s, its inventor was the same chemist who came up with synthetic rubber that formed under the combination of high pressure and intense heat. Early iterations weren’t super durable, but the chemist took his synthetic rubber balls to Wham-O, which fashioned a sturdier version—the same one it still sells today. Back in late 1965, Clark mainly threw, kicked or dribbled his around the family home. His older siblings bounced them all over. All apparently tickled Lamar, who mentioned the toy to commissioner Pete Rozelle, who, according to multiple accounts, landed with league owners on the phrase “Super Bowl” by borrowing from Super Ball.

Fast forward to this stretch of mostly magical postseasons. The owner who played with his Super Ball now runs a team that has played in four of the past five Super Bowls. His father, Clark says, “would love this era of Chiefs football, because he was, at his core, a super fan.”

To the ever-wider world of sports, the Kansas City Chiefs now present exactly what the Hunt family envisioned. The Chiefs play in a renovated stadium—the same structure from before, the frame hardly changed, but with everything else now different, enhanced, new. The franchise long ago formed a distinct soul that started, in all facets, with Lamar. It was tweaked and modernized by his children, who deployed Andy Reid levels of adaptability. This historical run helped. As did the superstar known as Pat. Both continued to grow in Kansas City, whether as a metropolis and within sports. The Chiefs retained their small-town ethos while ballooning into a brand of international importance. Home games unspooled like a mixture of college and pro football. At least those that didn’t take place overseas.

Eventually, an ideal loop formed. The Chiefs continued to help grow professional football, from Kansas to Germany and everywhere in between. But Kansas City also clung to its long-established organizational philosophies, growing at the pace it preferred, then capitalizing on that growth when everything from superstars to Super Bowls fell into place. Wasn’t the franchise just like Reid in that way? Formed by an impenetrable baseline but open to change when necessary, forever ready to adapt if any specific adaptation led everyone involved to the same place as Travis Kelce’s New Heights podcast. Like, well, embracing the world’s most famous super fan. Like following instincts, as long as they fall under the overall blueprint.

Clark Hunt thinks back to his father all the time. Lamar died in 2006, from complications of prostate cancer. When he started in professional football, the AFL had not yet merged with the NFL; a Super Bowl, of any sort, had never been staged. Clark considers how his father wanted to breathe pigskin into the Midwest, his desperate desire for expansion, so more of America—and, eventually, more of the world—could access this sport he loved so much. Without his influence, the NFL isn’t quite the behemoth it became; perhaps, without the Hunts, it’s not a behemoth at all. For certain, this team and the ones from earlier seasons in this run, wouldn’t enjoy—or be able to embrace—the grandest stage in American sports if the founders of their franchise hadn’t made it bigger, wider and ever-more magnificent. “It all ties,” Clark Hunt says.

On background

Word from sources with the 49ers is they feel great about their health going into Super Bowl LVIII. Given their injury history in recent seasons, this is no small deal.

Quote without context

“It’s fascinating. Someone who probably can’t play another position on the field is the starting quarterback for a multi-billion-dollar organization, and he’s running it like [it has] never been done before. He has answered every single question. Why do we need to defend this guy, man? It blows my mind continually.” — Will Hewlett, quarterbacks coach

Context

He’s talking Brock Purdy. Fairly, for what it’s worth.