How NFL's rookie wage scale restricts a player like Drew Lock from future earnings

As Denver Broncos fans will recall, 2019 second-round pick Drew Lock didn't sign his rookie contract until hours before the start of training camp, with his agent seeking a "quarterback premium" as part of the deal.

It's one of many things that has raised the issue about why it sometimes takes so long for rookies to sign their contracts when the rookie pay scale was designed, in part, to prevent lengthy holdouts.

The answer goes back to the number one reason for the pay scale: To control the costs of rookie salaries.

However, that meant only the signing bonuses, base salaries and the fully guaranteed amounts were set in advance. Along the way, teams started inserting their own additional language into the deals, sometimes seeking to make them even more favorable to the team than they already were.

When teams started adding offset clauses, payment schedules on signing bonuses, and the ability to void guarantees for whatever the reason may be, nobody should have been surprised that agents would start seeking additions of their own. That's particularly true for somebody like Drew Lock, who is represented by Tom Condon's agency — and Condon is known for being a tough negotiator.

It's understandable that team owners, front offices, veteran players and fans would want rookie salaries kept under control. But the current set-up favors the owners too much.

Some talk surrounding the collective bargaining agreement negotiations is that the NFL is pushing hard for an 18-game schedule. For the players, the obvious answer is to seek more money for player salaries — and that's certainly an item that can be negotiated.

But the players should be asking for adjustments to the rookie pay scale, too. Let's examine why.

Devil's in the details

The current rookie pay scale gives all draft picks a four-year contract, with a fully guaranteed signing bonus and some fully guaranteed base salary, depending on the round in which the player was drafted.

First-round picks get all four years of base salary fully guaranteed, second-round picks get the first two years of base salary that way, while others only get the first year fully guaranteed. Meanwhile, undrafted players aren't required to get fully guaranteed money in their deals.

However, the pay scale puts other conditions on drafted players, with some based on rounds taken and others that apply to all rounds. In the former case, players taken in the third through seventh rounds are eligible for salary escalators in the fourth season, but second-round picks are not.

First-round picks have fifth-year options that teams may exercise, which are injury-only guaranteed and become fully guaranteed at a later date. And no draft pick may discuss an extension with a team until after he finishes the third year of his deal, but undrafted players may discuss an extension after they finish two years.

These factors are important because they can affect how a player might cash in based on his performance and playing time. For example, 2016 third-round pick Justin Simmons got escalators in the final year of his rookie deal, but second-round pick from the same year, Adam Gotsis, did not. What Gotsis received had nothing to do with his play — it was simply because he got drafted in the second round.

Now think about what happens with Drew Lock. If he takes over as the starter in 2020 and plays at a high level then, and does it again in 2021, he wouldn't get any escalators in his contract. But somebody like Dre'Mont Jones would if he plays at a high level both of those seasons. It sounds like a good deal for Jones, but for Lock? Not so much.

In another example, Phillip Lindsay will be eligible to negotiate an extension if he completes the second year of his undrafted free agent contract. However, not one player the Broncos drafted in 2018 will be eligible for an extension, even if the likes of Bradley Chubb and Royce Freeman play at a high level.

More importantly, the length of most rookie contracts means the player has to wait that much longer for the chance to explore free agency. This is particularly true for first-round picks who play at a high level — they will get their fifth-year options exercised and, while they will get a considerable raise, the salaries are still a far cry from what they could get in an extension.

While it's not unusual to see first-round picks who play premium positions to get extensions, players who don't play such positions find themselves in a tougher spot. The perfect examples are the running backs — Ezekiel Elliott and Melvin Gordon are both trying to get that second contract now, but have no leverage because of the fifth-year option in place.

If players really want to maximize their earnings, they really need to focus on getting to that second contract earlier in their careers. That means, if the owners push hard for an 18-game schedule, the players must push hard to revamp the rookie pay scale.

What the players should examine is how to make the rookie pay scale fairer in terms of allowing rookies the chance to sooner explore free agency, while still keeping salaries low and doing a better job of getting rookies signed to their deals, rather than dragging out the process.

Here is what I would propose in a new rookie pay scale

• All terms and conditions for the contracts are set in stone per the CBA. In other words, neither teams nor agents may ask for anything to be added or adjusted to a contract. The owners can get something they want by having offset clauses be part of the contracts, while the agents (and thus the players) can get something they would favor by forbidding clauses that void all full guarantees, with the exception of a league suspension (in which case, players don't get the salary for the time they are suspended, while the team gains cap space for the weeks they don't have to pay the player).

• All rookie contracts are three years in length. Players are allowed to negotiate extensions with teams after they have completed two years of the contract.

• Salaries are still set based on the round in which a player is drafted and the player's position. Thus, premium positions (quarterbacks and pass rushers, most notably) will get the higher salaries in each round, while non-premium positions (running backs a notable one) will get lower salaries.

• All signing bonuses for draft picks are fully guaranteed. First-round picks get all three years of base salary fully guaranteed, second and third-round picks get the first year fully guaranteed and the second year injury-only guaranteed, and fourth and fifth-round picks get the first year fully guaranteed. Sixth and seventh-round picks would get no base salaries fully guaranteed upon signing, but there would be a point in which a full guarantee kicks in after 53-man rosters are finalized. Undrafted players get fully guaranteed money at the team's discretion.

• First, second and third-round picks would have a fourth-year team option that is fully guaranteed upon being exercised. This forces teams to consider the option more carefully and not just see it as a means to restrict the player's ability to negotiate a new deal.

• Fourth through seventh-round picks and undrafted players all enter restricted free agency. There would be first-round, second-round and original-round tenders. The system would work as it does now, but with a couple of differences.

First, players who get the tender may not sign the tender for the first two weeks of the NFL's league year. During that time, they may negotiate with their current team for an extension or listen to offers from other teams. A player is then free to sign an offer sheet from another team and his original team gets a period of time to match or decline the offer. Draft pick compensation, if any, will be awarded if a team decides not to match.

Second, after the two-week period ends, the player has the option to sign his tender or continue to field offers, with the deadlines to sign the tender still in place. However, when a player signs his tender, his salary becomes fully guaranteed, unlike the current system in which the money isn't guaranteed. And once he signs the tender, he may only negotiate an extension with his current team.

This system might make teams more open to signing players to offer sheets, because while they may not give up a second-round pick for a potential starter when they could just draft one, they could be more willing to give up a fourth or fifth-round pick for one. Also, it would benefit players because they could lock themselves into fully-guaranteed money at a certain point.

• The current system of escalators in the final year of contracts would be eliminated.

This system would get more money into players' hands because they would be a year closer to the opportunity to negotiate an extension or see a considerable raise in their fourth year that is fully guaranteed.

Teams would still get to have younger players at controlled costs for a brief period, but they wouldn't be able to ride it out as long as they do now. It would force them to look at the bigger picture when they build their rosters.

At the same time, it would give them some flexibility to keep players for four years -- it would just come at a higher price. They would also avoid holdouts, even if it means the teams don't get everything they want in a contract -- and they would at least get some things.

There are other ways in which the players could seek to get more money for salaries in exchange for giving the owners an 18-game season. However, the smartest thing is for players to ensure everyone gets the chance at that second contract earlier in their careers. That's the best way for players to maximize their earnings potential.

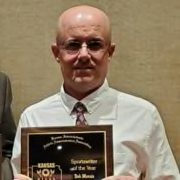

Follow Bob on Twitter @BobMorrisSports.