Patrick Mahomes and the Power of Imagination

Patrick Mahomes II chose football.

As a basketball player, Mahomes cranked 50-foot buzzer-beaters in middle school. He dominated at Whitehouse High, averaging 19.9 points, 3.4 assists, 6.7 rebounds, 4.0 steals, and .9 blocks per game as a junior. While it was his third sport, Mahomes’ high school athletic director had “no doubt” he could’ve played Division I basketball “if he focused on it."

Then there was baseball. As the son of a major league baseball player, his namesake, baseball stardom was his birthright, his destiny. Young Patrick got batting tips from Alex Rodriguez, took grounders in the company of Derek Jeter, shagged fly balls during warm-ups for the World Series. At Whitehouse, he started at every position but catcher, hit over .450, threw a no-hitter with 16 strikeouts, and was selected by the Detroit Tigers in the 37th round of the 2014 MLB draft, despite his firm commitment to Texas Tech.

But Patrick Mahomes II chose football. Why?

A basketball court is 90 feet long and 50 feet across — 4,500 square feet. To score, a round ball nine-and-a-half inches wide must pass through a round hoop exactly 18 inches across. Any of 10 players on the court at any given time can move the ball, pass the ball, steal the ball or shoot the ball, but ultimately, the focal point of the game of basketball is that 18-inch hoop hovering 10 feet above the floor, a point that can only realistically, consistently be reached by a shooter less than 40 feet away.

No two baseball stadiums are exactly alike, but each major league park contains anywhere between 2.34 and 2.67 acres of fair territory. A batted ball thus has somewhere between 101,000 and 116,000 square feet in which to safely land in play; mathematically, the nine players in the field must each protect more than two full basketball courts’ worth of space from a ball seeking open grass. If Rhode Island were a basketball court, a major league baseball field would be as big as Texas. And yet, for all its vastness, baseball still confines batters to a four-foot by six-foot box and still commands the baseball to cross a plate 17 inches wide. Baseball, like basketball, is defined by its limits.

Football is different.

At nearly 58,000 square feet, a football field dwarfs a basketball court, and while it occupies only half a baseball field’s total footprint, the ball may cross the plane of the end zone at any point along its 53 and 1/2 yard width — or be caught at any point within its 10-yard depth — to score a touchdown. A baseball must pass over a plate less than one percent as wide to be called a strike. A football field’s space is finite, but the possible ways to move 11 freakishly athletic human beings through that space in a game of football are effectively infinite.

Why did Patrick Mahomes choose football? Because football, like him, has no limits.

Football allows him to utilize all of his unique and prodigious talents. His otherworldly arm. His supernatural vision. His balance, speed, agility, and toughness, and perhaps his greatest gift of all — his mind.

PART I - IMAGINATION

“Imagination is more important than knowledge.” - Albert Einstein

Football is infinitely complex and always evolving. The game is played differently in high school than in college, and differently in college than in the NFL. Careers are short. The learning curve is steep. This is true for every position in pro football, but most true for the NFL quarterback. He is charged with memorizing every play in an offensive playbook thicker than War and Peace. He is responsible for studying the defenses of a dozen NFL teams, most of which will still manage to show him something he's never seen before. He must make split-second decisions and impossible throws as the clock ticks and the crowd roars.

To be successful, a quarterback must have knowledge of how to play the position: i.e., “facts, information, and skills acquired through experience or education.” But when he became the Chiefs’ starting quarterback in 2018, after one year backing up Alex Smith, Mahomes had limited experience — just 35 starts in three years at Texas Tech and a couple dozen more in high school. And while Mahomes’ performance on the whiteboard in his pre-draft meeting with Andy Reid is now legend in Chiefs’ Kingdom, Mahomes himself admitted that he “didn’t understand how to read defenses” at this early stage of his career.

Yet Mahomes would go on to produce more “how the hell did he do that?” plays in 2018 than he would in 2019, and not by coincidence. At this stage of his career, knowledge was less important to him than imagination: the ability of the mind to be creative or resourceful.

Mahomes’ imagination was on full display long before he became the Chiefs’ starting quarterback. Nearly every member of the Kansas City Chiefs from 2017 on has a story about Patrick Mahomes’ practices. Tyreek Hill said he knew Mahomes would be special from his first throw at his first training camp. Longtime Chiefs’ pass-rusher Justin Houston recalled a moment from Mahomes’ first OTAs:

“He didn’t know the offense, he didn’t know what he was doing, he rolled to his right, the defense opened up, and he threw 30 yards down the field to the left. I’ve been around for a little while, and not a lot of guys can do that.”

What Houston saw at those first OTAs captures the essence of Mahomes’ mind. Not many guys can do what Mahomes does because they lack his unique arm talent. But they also lack his imagination.

Because Mahomes started playing quarterback relatively late for a future pro, he had comparatively little coaching in what not to do. Take, for example, Mahomes’ ridiculous Week 15, 2018, touchdown pass against the Los Angeles Chargers:

Throw it away?

— NFL (@NFL) December 14, 2018

That's not the way @patrickmahomes5 rolls. Touchdown, @Chiefs!#LACvsKC

📺: @nflnetwork + @NFLonFOX

📱+💻: https://t.co/DJUityQHC9 https://t.co/62w3y3yuEd

Joe Buck is, by his standards, incredulous. Troy Aikman, on the other hand — as Football Guy as Football Guys come — delivers a line that might as well have come straight from a book called “How to Play Quarterback”: “It’s a risky throw, there’s some danger in that when you start throwing it back towards the middle.”

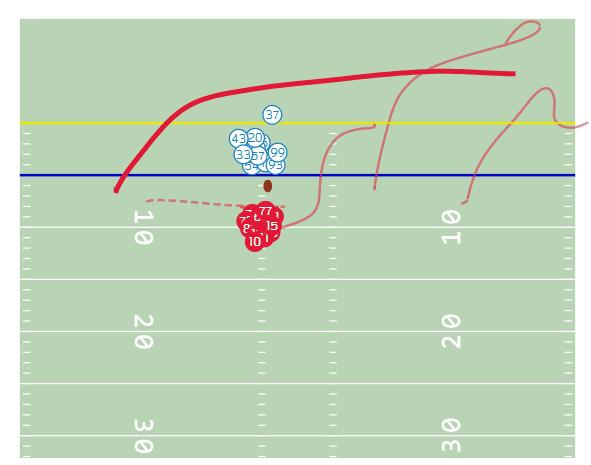

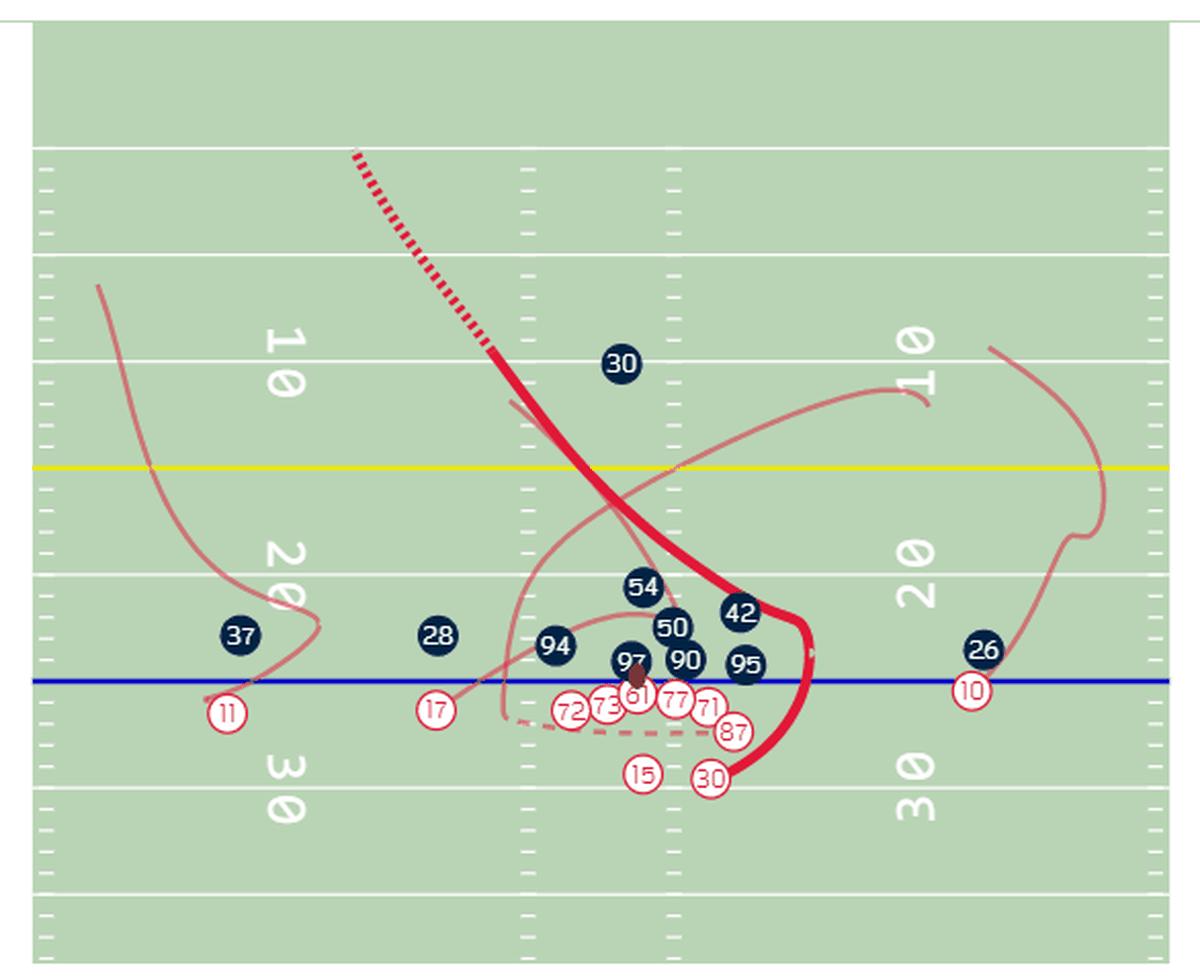

But when you really break the play down, the only players in danger are wearing Chargers’ uniforms. Sure, Mahomes has to throw the ball sidearm, while getting hit and driven out of bounds by safety Adrian Phillips, but DeMarcus Robinson is open. Then-rookie Derwin James, #33, has tight coverage on Robinson for 98% of the play. But at the last moment, perhaps seeing Mahomes going out of bounds, he lets up for a split second - and the Chiefs get a touchdown.

As Titans’ left tackle Taylor Lewan put it: “I’ve never played quarterback, but I’ve heard coaches say ‘don’t do this,’ and he does those things, and they work out tremendously.”

The following week, at Seattle, Mahomes unleashed an even weirder throw, this time resulting in a touchdown for Charcandrick West:

Only @PatrickMahomes5 can make this throw 😱

— NFL (@NFL) December 24, 2018

Touchdown, @Chiefs! #ChiefsKingdom

📺: #KCvsSEA on NBC https://t.co/PaFxSXDjcY

Again, Mahomes breaks pretty much every rule of playing quarterback: throwing on the run, against his body, towards the middle of the field, into traffic. Longtime football fans watch this play and know Mahomes is doing something wrong — he has to be — because we’ve been conditioned, through color commentary, to believe that everything Mahomes does on this play is risky or dangerous. But once again, when you break the play down, Mahomes has a clear window to an open receiver. All it took for him to take advantage of that window was a little imagination:

Patrick Mahomes, thankfully, never had his imagination coached out of him. That imagination allowed him to win MVP in his first season as an NFL quarterback, without the knowledge of how to read defenses. “Imagination,” Albert Einstein wrote, “is more important than knowledge.” For Patrick Mahomes, in 2018 at least, these words rang true.

Stay tuned for Part II: Knowledge.

2018 belonged to #MVPat🚀

— Kansas City Chiefs (@Chiefs) August 1, 2019

📺: #nflnetwork pic.twitter.com/BpDAHCaoQt