Week 6 EPA Power Rankings: Does a mobile QB help a running back?

Mark Ingram is on pace for a career high 1,190 rushing yards. He's also seeing his best career yards per carry. Coincidentally, this is also the first year he has played with Lamar Jackson. Or is it coincidence at all?

We've seen cases like this in the past. Alfred Morris is a free agent after spending the past three seasons as a backup, while spending his first three seasons rushing for over 1,000 yards and being selected twice for the Pro Bowl. His quarterback those first three seasons was Robert Griffin III. Marshawn Lynch was traded away by Buffalo for a couple mid-round picks and went on to set his career highs in rushing yards, yards per carry, and touchdowns once he was paired with Russell Wilson.

Running backs don't have to be paired with a mobile quarterback to succeed, but there is anecdotal evidence that it helps. We're going to see if we can detect just how helpful it is using the publicly available data from nflscrapR.

But first, let's check in on Mark Ingram, Lamar Jackson, and the rest of the 2019 NFL teams with this week's EPA power ranks.

(Reminder: Expected Points uses data from previous NFL seasons to determine how many points a team is likely to come away with on a given play, based on down, distance, time remaining, and field position. The difference in expected points at the start of a play and expected points at the end is referred to as expected points added, or EPA.)

San Francisco took a firm hold of the No. 2 spot this week after a dominating win over the Cleveland Browns on Monday night. The Browns, on the other hand, saw the biggest fall of the week, as both their offensive and defensive EPA went the wrong direction. The Falcons continued their decline and are now in the bottom-5 in the league. Their defense is the worst defense of any team not named the Dolphins in the NFL. The four remaining winless teams round out the bottom of the list.

The Eagles were the biggest risers of the week, moving up 10 spots on the back of a 10-sack performance from their defense. Houston took the opposite route to a rise in the rankings with a 53-point performance against the Falcons. Houston now features the third-best offense by EPA.

As of right now, there are three teams in the top-10 in both offensive EPA and defensive EPA:

The top four offenses in the league all feature quarterbacks that are a legitimate threat on the ground (Chiefs, Cowboys, Texans, Ravens). Which brings us back to the question I posited at the beginning of this piece: does a mobile QB have a measurable impact on the success of their running backs?

The theory behind a running back being helped by a mobile quarterback is that at least one defender has to be responsible for defending the edge that a quarterback would attack on a read option. If the quarterback hands the ball off, but maintains the threat of keeping it, he's taking one defender from the box away from the play, without even blocking him. And removing defenders in the box is a key part of rushing successfully.

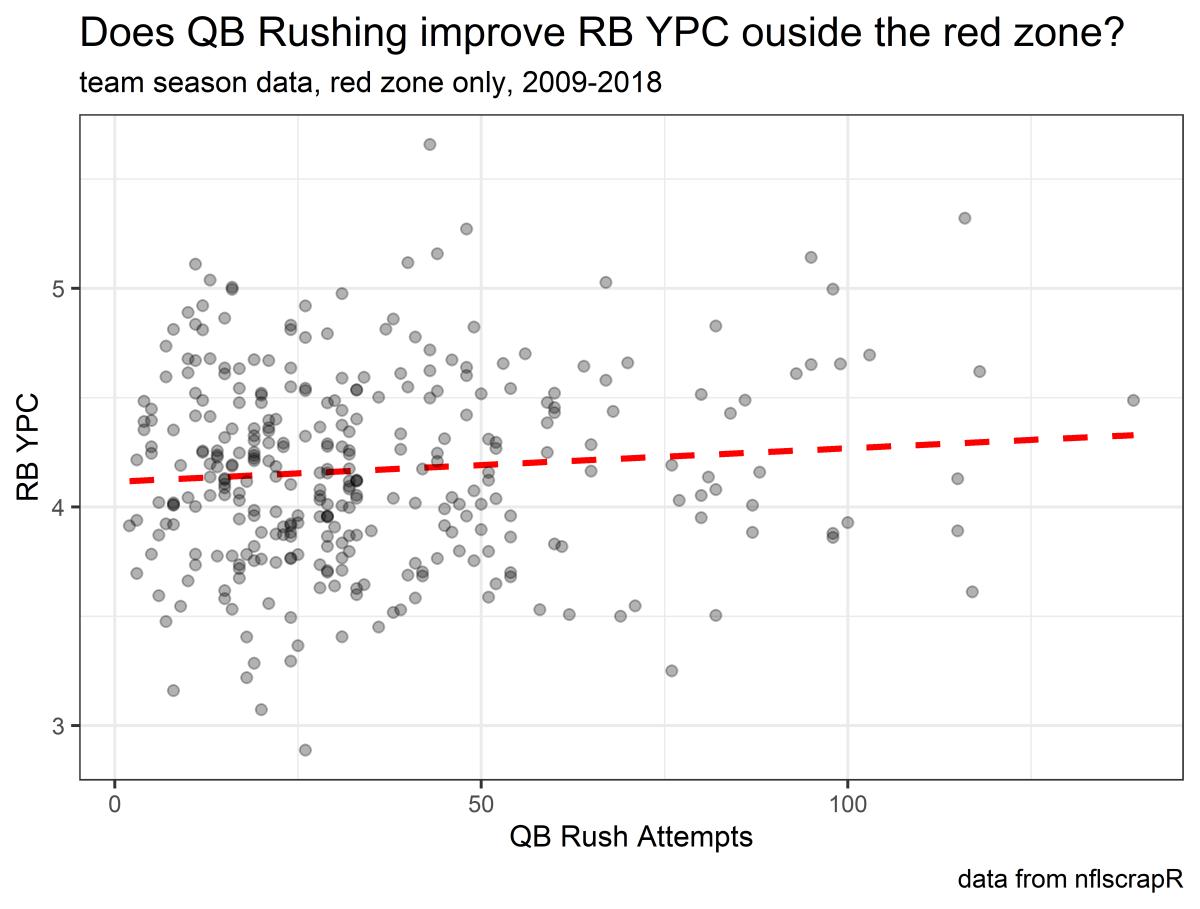

If this is true, we should be able to see it somewhere in the data. To start, I looked at how often a quarterback runs (designed + scrambles) and compared it to his running backs' yards per carry.

Normally when evaluating success on the field, I'd prefer to use EPA. My reasoning for using YPC instead is that EPA can capture a lot of coaching decisions rather than just running back production. I also selected only run plays between the 20 yard lines. But for what it's worth, I ran this same chart with running back EPA/carry and it was basically the same correlation (or lack thereof).

There is a very slight positive correlation here, but it's not strong enough to believe there's a signal there. With an r-squared value of 0.01 and a p-value of 0.07, it's safe to say this is just noise.

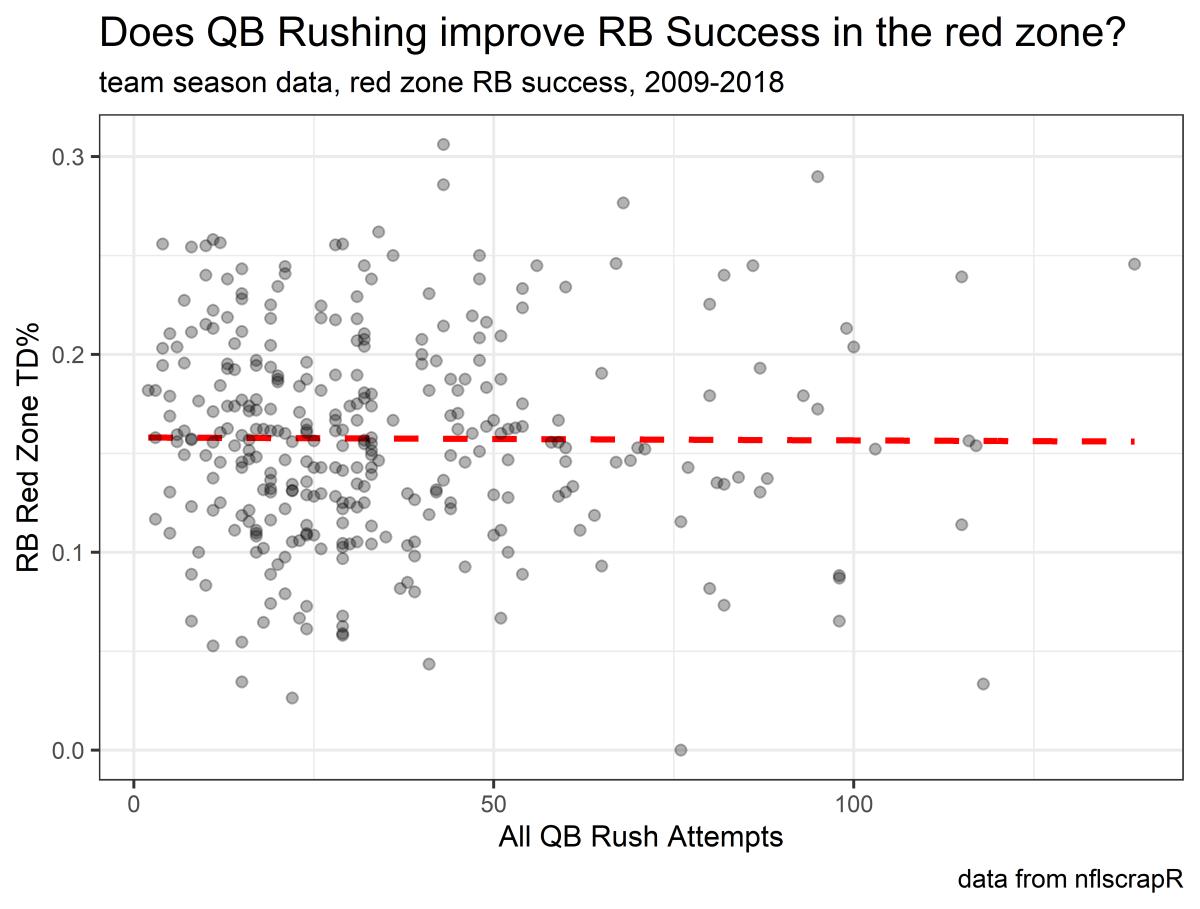

Perhaps we could see some more production inside the red zone if defenders are forced to keep a closer eye on a rushing quarterback.

Again, we can't find any sort of correlation here. I also tested running back YPC and EPA/carry here to no greater success than this. And in place of just basic quarterback rush attempts, I also tried quarterback total EPA and EPA/carry, to see if high-volume, successful rushing quarterbacks showed up in the data at all, but it wasn't meaningfully different either.

Furthermore, check out that one dot all the way on the bottom of this chart. That's the 2017 Seattle Seahawks. The 2017 Seahawks were one of the worst (running back) rushing teams...well, ever. They finished with exactly one rushing touchdown from their running backs, a 30-yard carry from J.D. McKissic, even with Russell Wilson tallying the second-most rushing yards of his career (586). That anecdote about Lynch breaking out when paired with Wilson is being destroyed by the same team within five years.

As of right now, there doesn't seem to be any significant boost to running back success when paired with a mobile quarterback. Maybe it's just too small of a portion of running back success to be detected with the data available here.

After all, Five Thirty Eight's Josh Hermsmeyer was already able to explain 80% of a back's YPC strictly based on the number of men in the box. Maybe a mobile quarterback invites more defenders into the box, negating the advantage of taking a defender away from the play to spy the QB. I do still believe there could be an advantage to running backs with a mobile quarterback. Perhaps shotgun runs are more successful, or maybe read-options specifically lead to better runs, but at this moment, that data isn't publicly available. With more data, there would certainly be more avenues to explore in this venture.