How New Orleans got an NFL Team by Mike Detillier - Part 4

In 2003, then WWL Radio Sports Director, Buddy Diliberto, spoke to me about obtaining as much information as possible on how New Orleans got an NFL team.

Diliberto first covered the beginning of getting a professional football team in the newspaper business and then covered the New Orleans Saints on television and the radio.

We both went to a host of different sources to get the behind the scenes information for the book, but in early 2005 Diliberto passed away, and I put our information away.

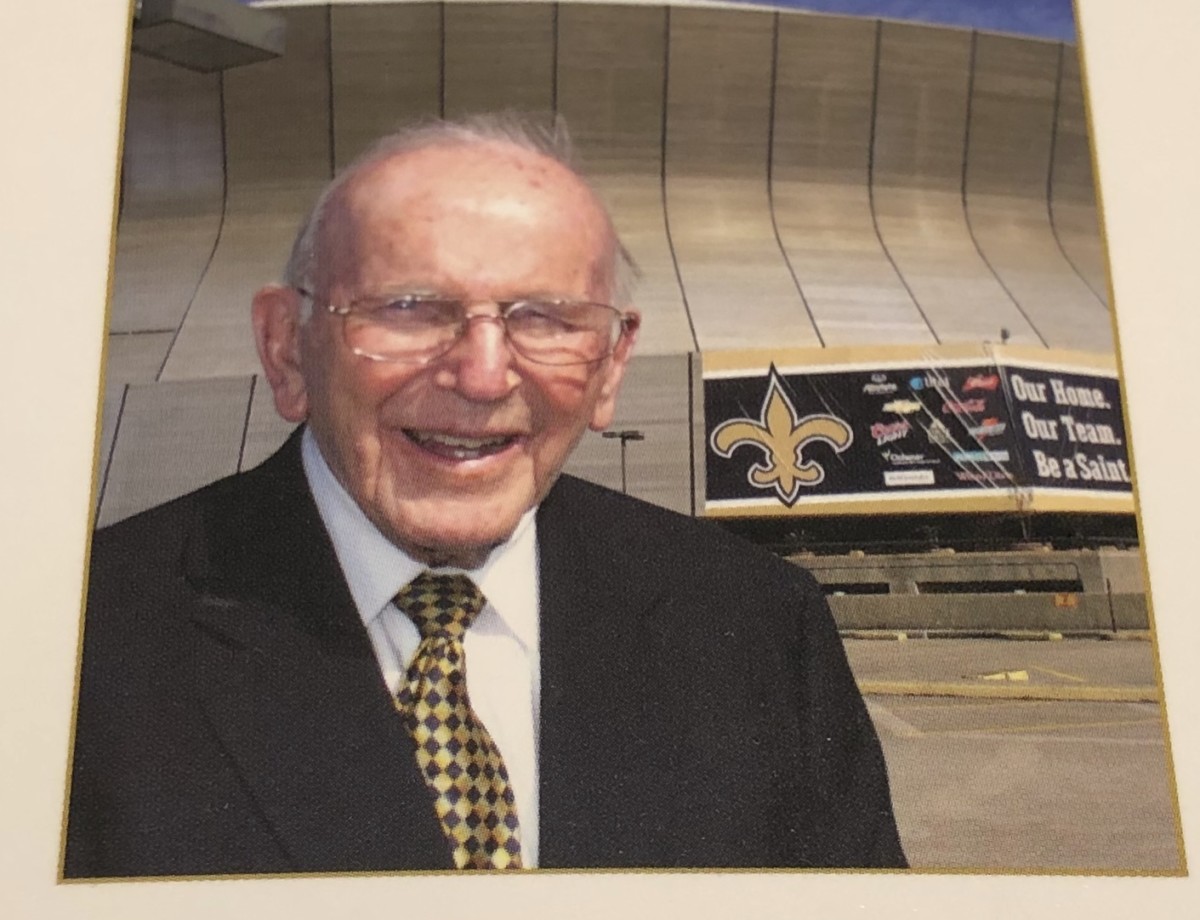

In this nine-part series on "How New Orleans got an NFL Team," I will give you the information from a host of sources. Mainly the most vital piece to get the New Orleans Saints was Dave Dixon. Dixon worked behind the scenes to place a team in New Orleans, and later he became the Father of the Louisiana Superdome.

PART 4

While Dave Dixon was fighting off other Southern towns to land an NFL team, he also received “Friendly Fire” from the local newspaper- the Times-Picayune.

“We had things moving in the right direction with fan support, we had made major connections with the heavyweights in the NFL and also the Commissioner of the NFL in Pete Rozelle, but I had to fight off obstacles laid out on the ground by “The Editor” of the Times-Picayune in George W. Healy, Jr.,” Dixon said.

“The Times-Picayune of 2003 is a far different paper from back in the 1950s and 1960s and a better overall paper today. They had phenomenal writers back then, legendary writers, but the paper also had an ugly edge to change and progress when it came down to one man who gave commentary. Healy was someone very few people went toe-to-toe with. You didn’t cross him. He was powerful and used that power of the pen to sway people to his way of thinking.

Newspapers and editorial content still carried a lot of weight for many readers, but “The Editor” did not want to embrace change and wanted to stay living in the 1930s and 1940s. He was famous for being stubborn, unpredictable, and unwavering in his stances. He did not want professional sports in New Orleans, and he did not hide that fact. But he was also a man seeing changes in how people got their news and commentary in the early 1960s. He never considered radio a threat, but television was different.

I have to laugh to hear these commentators and folks on talk-shows say today, “I wish we lived back in the day when newscasters just gave us the straight news and no commentary.” Really-You don’t know history if you say that comment. They must not teach that in journalism class anymore. Since they first started printing newspapers, you got commentary, and you got their angle to a story. That’s just fact. Television gave you the straight news back then, but you also got daily commentary from Edward R. Murrow, Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley, Chet Huntley, and Howard K. Smith. Today you get opinions from commentators 24/7 on different channels.

Some have no clue what they are talking about, and some are hand-fed information from politicians, political parties, or sources they know that agree with their views on the world. Back then, you got the facts, but they also gave you their commentary on certain events, but it was only for a half-hour on television. Newspapers didn’t want television walking on their hallowed grounds, and certain people who owned newspapers or an editor of a paper got very ugly about the change on how people got information and commentary. I felt the wrath of my own hometown newspaper.”

Dixon was warned that influential forces were going to fight him on getting professional sports in New Orleans.

“Behind my back, he spoke ill of me to many influential people and told them I was doing this to be the new owner of the professional football team, and I was in it for the notoriety. I took a different point of view from him, and he was going to try and make an example of me to anyone else who crossed him. I was also told “The Editor” didn’t want professional sports in New Orleans and wanted to keep the city a college and high school sports town, cover the horse-racing world, cover the outdoor sports world some, a little professional baseball, not very much on professional basketball and he thought of professional football the same way. He had his reasons, and he literally wanted to keep this area in a “time bubble” and told his sportswriters to push Tulane and LSU football more, even in the off-season.”

Dixon got word that “The Editor” had given strict orders, no matter if the games were being played in New Orleans, to not report on professional football on a daily basis.

“We started to get professional pre-season games and “The Editor,” tells his sportswriters they can write about pro football, but not every day. OK, we are trying to sell a game, and there’s not much happening in the sports world in August, and he is saying even with pro football coming to town, don’t write about it every day leading up to the game in his own city. Virtually every one of the sportswriters told me what was happening, and I had to come up with a gameplan to push the game.”

States-Item Sportswriter/Columnist Peter Finney says Dixon became the ultimate “chess” player in his battle with Healy.

“David (Dixon) was the ultimate mover and shaker in this game with “The Editor.” Healy was not real vocal with me about leaking the information on how we covered the local exhibition games, and he saved most of his anger for Buddy (Diliberto) and (Bob) Roesler. But it was all three of us who leaked that information to Dixon.

Dave came up with a plan on the days we didn’t write about professional football to buy full-page advertisements in the sports page about the game. Healy was irate about it, but the powers to be who owned the newspaper knew they didn’t give away those full-page ads. Dixon threw the money card at him. He paid for it out of his own pocket. After that, any information about the NFL, AFL, and especially when the team was close to coming to New Orleans had to be filtered through him. He wrote commentary on what he considered the negative side of professional sports. He wrote negative commentary on the Sugar Bowl game, especially when they started to invite teams that had integrated from the East and Midwest. He also was against and wrote in negative terms about the city hosting the AFL All-Star game later one. He was caught with ownership wanting to push professional football and making money on the games and selling newspapers and his desire to not want it in New Orleans. But Dixon won the battle.”

“I had my issues with him about the Saints, wanting to pursue pro basketball, Super Bowl games in New Orleans and also the Superdome,” Dixon added. “He wanted none of that for our city. He had to change and I can say I thought the writers did an exceptional job in the months leading up to New Orleans getting the franchise and covering the team, but “The Editor” had to be dragged screaming and kicking into the new world. Every other hometown newspaper was backing the efforts of others to get professional sports in the Deep South and he did everything he could to stop it. Shameful, but we won the war against the powers to be.”

The Money Game Changes the Way they covered Pro Football in New Orleans.

Dave Dixon went on to say he was fascinated to see what would happen in early 1964 when the television contracts for both the National Football League and the American Football League would come up for the 1965 season and beyond.

WDSU (Channel 6) Sports Director Wayne Mack in a one-on-one interview in 1985 told me that he was tipped off something big was going to happen by WDSU Television station owner Edgar Stern, Jr.

“The Boss always knew things others had no idea about, and one day in early 1964 he walks into the newsroom and tells me “Wayne, get ready to start covering professional football,” and he walked away quickly. Stern didn’t say another word to me. I did a little work and found out that both television contracts were coming up for renewals. The major newspapers in the Northeast were saying that CBS, who had the rights to NFL games, would not get into a bidding war for professional football. CBS had just made major cuts to their news division, and most felt they would pass on the National Football League games despite television ratings that were enormous on Sunday afternoons. Really no one in the sports world knew if the American Football League would even survive back then, and the owners were losing tremendous amounts of money. Who knew would be offered for their games.”

Mack said he was shocked when word of a new deal came over the newspaper wires.

“I couldn’t believe that CBS had paid $28.2 million dollars for the television rights to the National Football League games for 1965 and 1966. It was a staggering amount of money at that time and I thought that offer would have been made by NBC, not CBS. Then CBS acquires the rights to the NFL Championship Game, and CBS and the NFL agreed to extend the deal another year for $31.8 million.

I was devastated until two days later, and I’m behind the curtains for The Midday Show, and Edgar Stern comes up behind me, and I turn quickly, and I tell him, “I can’t believe CBS got the rights to the National Football League games.” Stern turned quickly and told me, “The game is not over yet Wayne, and we got a little time on the clock for a few plays.”

I wondered what he was talking about. Days later, I found out.

Mack went on to talk about how the games for professional football were spread out on all three networks.

“CBS had the regular-season games for the National Football League, but NBC had the rights early on for the radio and television coverage to the NFL Championship Game,” Mack said. “The contracts were separate. The American Football League was on ABC, but NBC had the rights to the 1963 AFL Championship game. NBC also had the Pro Bowl games. They were playing “money checkers” with the pro game coverage. But NBC was really known sports-wise for its Saturday Afternoon Major League Baseball Game of the Week coverage and the Rose Bowl game. Days after CBS got the rights to the NFL games, someone in the newsroom ripped off a UPI story that NBC had bought the exclusive rights to the American Football League games starting in 1965, and it was a 5-year deal for $36 million dollars.

Then NBC acquires the rights to play the Orange Bowl game on the network. On January 1, 1965, Texas vs. Alabama in the Orange Bowl became the first college bowl game to be televised in prime time. It changed the way WDSU and every other NBC station covered professional football. And it meant that the American Football League had survived. I never get emotional about things like that, but I was emotional that those events had changed the way I would cover professional football, and now we had the Rose Bowl and Orange Bowl games. And we still had Major League Baseball also. NBC was now playing in the big leagues, sports-wise and so was I at Channel 6 (WDSU).”

Buddy Diliberto said that the new television contract with NBC for the American Football League saved the league, and the coverage of professional football opened up the television door for him.

“I really think other than the merger that moment the AFL got that huge money deal from NBC really saved the league,” Diliberto said. “Teams in the AFL were really in bad shape financially, and then they started borrowing money from NBC to pay players and go after the top college talent. It was a savior to the AFL, and that moment pushed the NFL owners to look at a merger. It may have not been discussed at that time, but it was the pivotal moment in time for the National Football League to look at cutting a deal with the AFL. They had a great deal, but they didn’t like the bidding wars for college players, and it changes their feelings on how the general public felt about the AFL.

It did change the way NBC covered pro football, but it also sort of changed my life. The local ABC station, Channel 12 at that time, called me and wanted me to take over doing sports coverage on television. I turned it down at first. But Hap Glaudi, who I had worked with at the paper before he went to take over the sports department at WWL (Channel 4-CBS), convinced me to take the television spot. That moment changed most of our lives back then.

But what the American Football League needed in early 1964 was a football celebrity that would throw television, newspaper, and radio “heat” on the league. In less than a year-they landed him.”