The Power of Joe Namath: How New Orleans got an NFL Team - Part 5

In 2003, then WWL Radio Sports Director, Buddy Diliberto, spoke to me about obtaining as much information as possible on how New Orleans got an NFL team.

Diliberto first covered the beginning of getting a professional football team in the newspaper business and then covered the New Orleans Saints on television and the radio.

We both went to a host of different sources to get the behind the scenes information for the book, but in early 2005 Diliberto passed away, and I put our information away.

In this nine-part series on "How New Orleans got an NFL Team," I will give you the information from a host of sources. Mainly the most vital piece to get the New Orleans Saints was Dave Dixon. Dixon worked behind the scenes to place a team in New Orleans, and later he became the Father of the Louisiana Superdome.

PART 5 - The Influence of "Broadway Joe" Namath

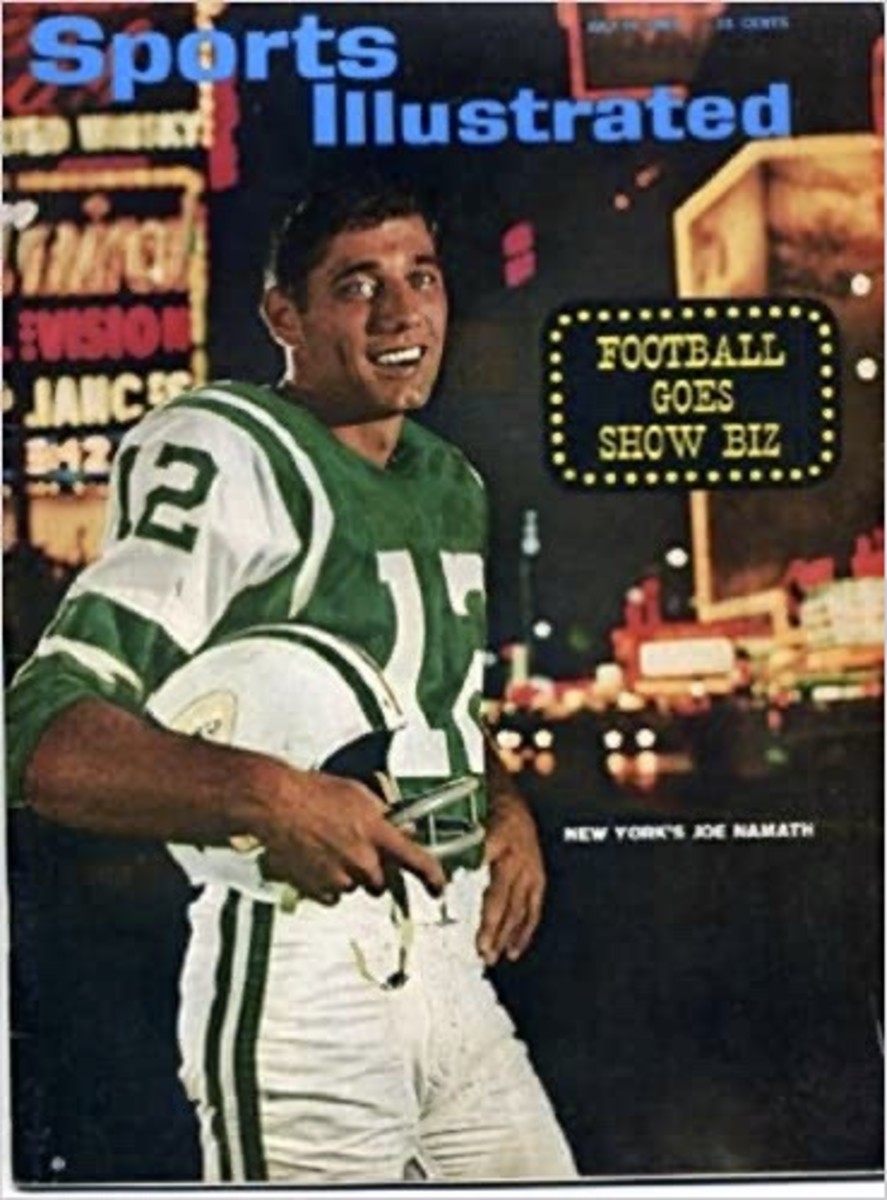

With a new television contract in hand for both leagues, the American Football League made a move for a player that changed the course of history for the AFL, helped force a merger, and it aided the expansion of both leagues, including New Orleans.

After Mike Ditka took over the head coaching job with the New Orleans Saints, he was replaced on WWL Radio’s weekly Casino show spot in Mississippi by former Kansas City Chiefs and New Orleans Saints Head Coach Hank Stram.

Stram was adamant about Namath's positive impact in the American Football League and how his contract "didn’t nudge, but shoved" the NFL owners to negotiate a merger deal with the AFL.

“Joe Namath made us change the way all of us drafted college players,” Stram said on one of the Casino shows. “We had good teams in the AFL with the (Buffalo) Bills, the San Diego Chargers, and we had an excellent team in Kansas City and everyone knew Al Davis had changed the league in his approach, his ability to attack the deep part of the field with the pass and he had a great eye for talent in Oakland. As much as I disliked some of his methods of dealing with folks at times, he was truly brilliant. We needed to bulk up on offense because Namath was going to change our league.

You couldn’t just win with defense; you needed to change the lights on the scoreboard too. The Jets had maneuvered with the Houston Oilers and gotten the top overall choice in 1965. The Jets owner, Sonny Werblin, had come from the entertainment world. He knew how to sell a product. He had done that on Broadway and on television. He was going to sell Namath to the general public and do it in the “Mecca of the Media World”, New York City. That’s not a knock on Namath. He was immensely gifted, but he would not have been marketed in the same manner in Houston, Denver, Kansas City, or Oakland. That’s just fact.

But all of us in the AFL thought the New York Giants would pick Namath with the top pick in the NFL draft. Sonny Werblin and the Jets had beaten out the Giants the year before for Matt Snell from Ohio State. Matt was a tremendous running back for the Buckeyes, and Werblin stole him away from the Giants. We all thought this would be a New York vs. New York showdown for Namath.”

Stram went on to talk about meeting with his owner Lamar Hunt with the Chiefs on trying to outmaneuver other teams in the AFL with the strong possibility of Namath signing with the Jets.

“Lamar Hunt and I met a week before the draft to talk strategy,” Stram said. “The 1965 draft was held in late November of 1964 after the college football ended its regular season, but before the bowl games. So we haven’t even finished our 1964 AFL season, we have weeks left to play, and we are having a draft. I told Lamar that we needed to get playmakers on offense to offset Namath. Lamar asked me, “Hank, who do you want?”

I told him we needed three wide receivers and Lloyd Wells, who was a super scout for us and also someone who could do some behind the scenes things to insure us of getting players by forming a good relationship with them and at times hiding players away from the NFL too. Lloyd knew everyone in the Southwest Athletic Conference, and he had great relationships with players and families, and he sold the American Football League to many of the black players. We called him “The Judge.” When the old guard NFL saw we were signing players in numbers from the historically black colleges, they jumped in too. “The Judge” was a huge part of our success with the Chiefs, and he later went work for Muhammad Ali.

Lloyd told me we have to get a wide-out from Prairie View in Otis Taylor and two other ends in Frank Pitts, from Southern University in Baton Rouge and Gloster Richardson from Jackson State. Otis was a great catch for us, I truly believe he belongs in the NFL Hall of Fame, but we did a lot of maneuvering to keep the NFL away from him. We signed all three wide receivers, and all were excellent contributors to the organization. But Otis (Taylor) was special working with Lenny (Dawson).

We had long courted Gale Sayers, who was at Kansas University. He grew up in Nebraska and was a great running back for the Jayhawks. We had a terrific relationship with him, and we thought we had him. I never saw a running back run as fast sideways as he could forward like Gale could do. The only guy I have seen in the NFL since that could make good tacklers miss in the open-field like Sayers was Barry Sanders when he was with the Detroit Lions. Gale was a tremendous football player and a superb man in life. So Lamar picked him for us in Round One.

The other back I wanted was Jim Nance, who was a terrific running back/fullback with Syracuse. I hadn’t got out Jim Nance’s name good to Lamar, and he told me we couldn’t pick him. I asked him why and he said that Nance had grown up in Pennsylvania and played at Syracuse, and the Boston Patriots wanted him. I got angry and told Lamar, “Boss, are you working fulltime for the Chiefs or for the AFL?”

I know I was a pain to him about certain things like that, but he was looking out for the good of the league too. Lamar was a very soft-spoken man, and all he told me was, “Hank, give me another name?”

So I told him, Mike Curtis, from Duke. Mike was a tremendous fullback at Duke, he was a two-time all-conference fullback there, and I loved his aggressive play. Curtis was a total team player. We had an assistant coach with the Chiefs, and he was closely connected to the head coach at Duke at that time. We made a great offer to Curtis, but Mike Curtis signed on instead with the Baltimore Colts. The Colts switched him fulltime to linebacker, and Mike became a tremendous middle linebacker for them. Years later, Nance tells me, “Coach Stram, I was always a big fan of the Chiefs, and I hoped you guys would draft me.” I just couldn’t believe it.

But that was Lamar, and he was trying to help other teams in the league too. But we didn’t draft Nance and Curtis signs with Baltimore. The biggest regret in my time in Kansas City was not to offer a contract that Gale Sayers couldn’t turn down. He ends up signing with the Chicago Bears. We made him a good deal, but we should have offered him a great deal. We messed that up. All of us thought his connections to our area would make the difference, but it didn’t, and I give “Ole Papa Bear” (George Halas) credit, he did a little maneuvering around with Sayers also late in the process to get him to sign on with the Bears. I was never so angry about losing a player like I was about losing Sayers to the Bears. Lamar was not stingy with money, but it was our initial offer that should have been a “Godfather” offer he couldn’t refuse.”

Stram said that he kept his eyes square on who would select Namath in the NFL.

“The NFL is having its draft in late November too, and I’m interested to see if the Giants select Namath. Instead, the Giants pick Tucker Frederickson with the top pick, and he was a good running back from Auburn, so it became who selects Namath now. But I was stunned they passed on Namath. I stuck my head in Lamar Hunt’s office and asked him which team selected Namath? He told me that 10 picks into the first round no team in the NFL had selected Namath.

"We both thought this was a set-up by the NFL."

The NFL wanted Namath in New York, and they gave a gift to the Giants by letting them select the running back they wanted in Frederickson and then would somehow/someway “plant” Namath in New York. That sounded like something Pete Rozelle would do. A few minutes later, Hunt walked on the practice field and told me, “Coach, the St. Louis Cardinals just selected Joe Namath. We better get ready to play against him in the AFL. No way Bill Bidwell gets him away from Werblin and the Jets.”

Lamar was right. The Cardinals offered him a contract worth $200,000 and a new Lincoln Continental, and he signed with the Jets for $427,000 and a new car. It was the largest contract ever given to a player at that time. He earned every penny for his talent and what he did for our league.

That signing dramatically changed the American Football League. When Joe Namath was healthy, he was the most gifted player in the AFL. He was someone everyone wanted to watch, and that move forced the hand of the NFL to seek a merger, expand the league with more teams, and Namath was box-office. Instead of having maybe 20,000 people to watch the Jets play, now they have 35,000 to 40,000 folks watching because of Namath. His contract with the Jets had the NFL wetting their pants. They thought they would go broke going against us for players. That new television contract with NBC and Namath signing with the Jets forced the merger between the AFL and the NFL later on, and cities like Miami, Atlanta, New Orleans, and Cincinnati got professional football because of it.”

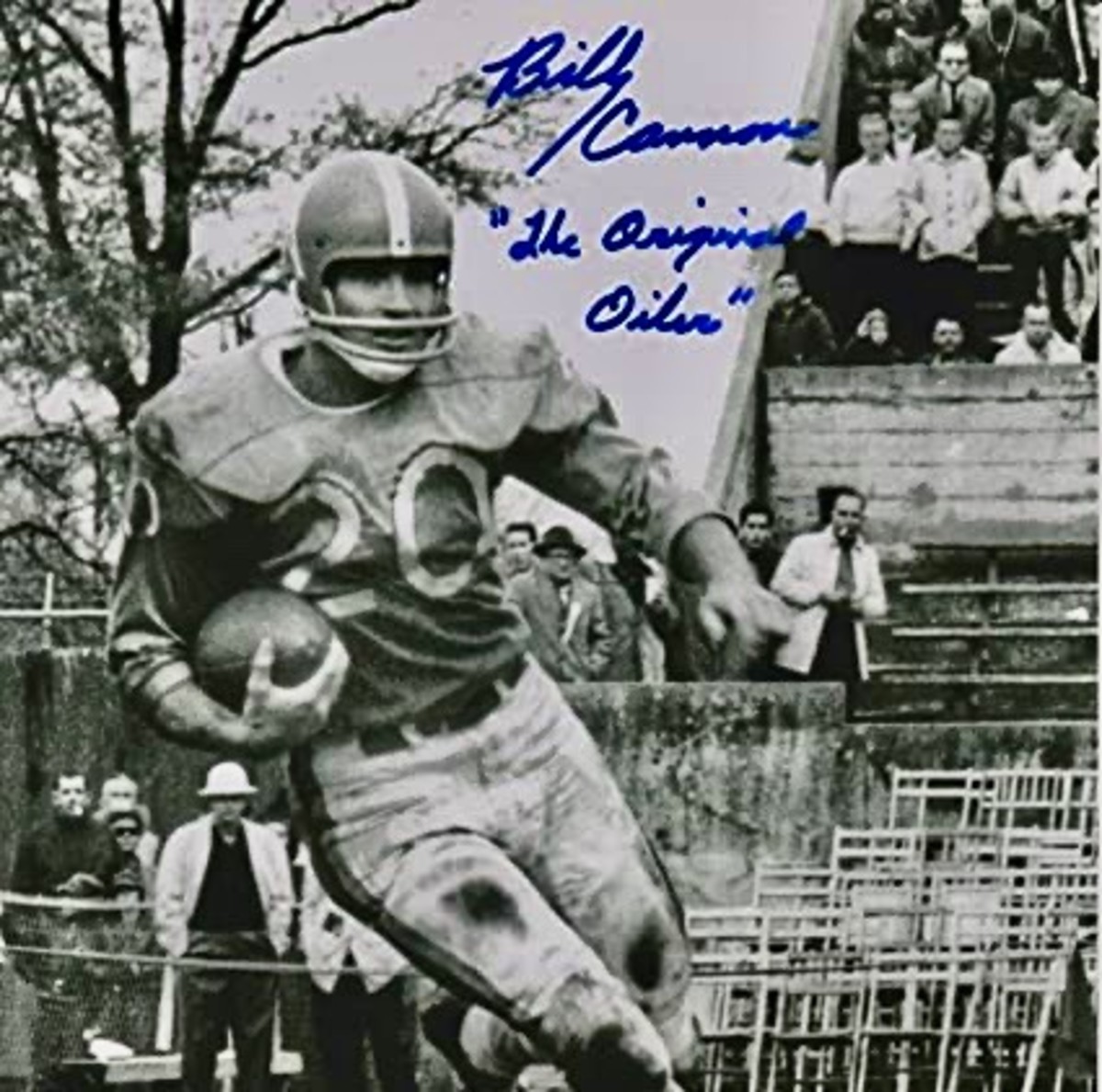

In 2010 LSU 1959 Heisman Trophy winning halfback Billy Cannon, who became the first big-time college player to sign with the American Football League, joined Bobby Hebert and me on our Monday Night WWL’s 2nd Guess Show and he gave Namath the highest of endorsements for what he did for the new league and his talents.

“Joe (Namath) was the most physically gifted football player I ever played against,” Cannon said.

“Before his knees went, real bad-he was All-World. Everyone remembers Super Bowl III, and that changed the perception of the AFL to many, but Joe threw a ball like no one I have ever seen. Some players were upset that he got all that money before he played a game in the league, but guess what, so did I. I told the guys that Namath making that kind of money helps all of us, not just him. It had folks paying a lot more attention to the AFL because of Namath. I read and hear some of these “stat geeks” today that never played a game in their life and just want to give you statistics about Namath, but numbers don’t tell you the whole story. He was a star passer in a league where you could “bump and run” a wide receiver all the way downfield and not get a penalty for it. Guys were unloading on Namath. We saw film where defenders were hitting Namath 5 or 6 seconds after he threw the ball, and it was legal to do.

I’m with the Oakland Raiders, and I tell Al Davis, “Al, this is borderline assault on Namath the way we hit him after the throw,” and Davis tells me, “Cannon, how would you suggest we stop him?” That was Al Davis. Joe was one tough guy.

Let these quarterbacks today play under those rules and let me see their numbers. Joe Namath changed the American Football League like no other player, and he opened up the leagues to expand so people could see pro football in more places, like New Orleans.”

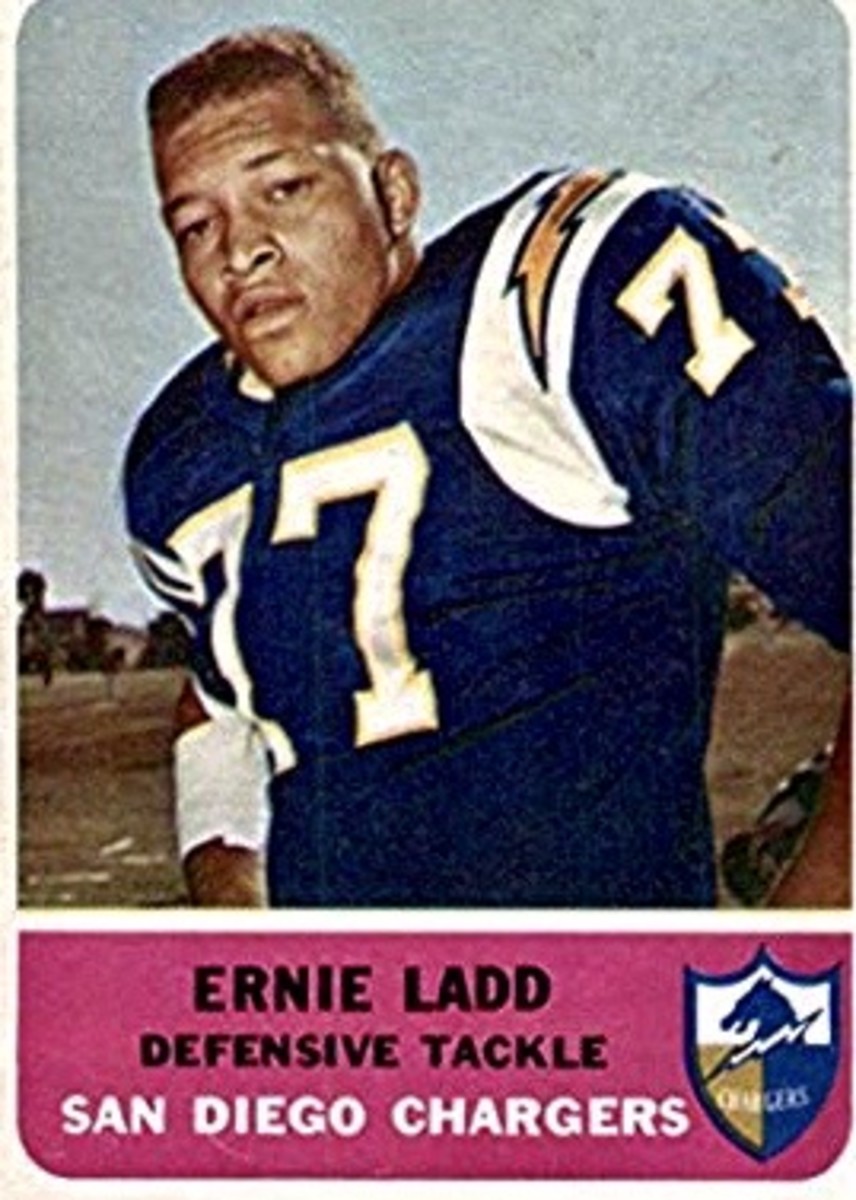

In the summer of 2004, WWL-Radio had an NFL Throwback Show with myself and Buddy Diliberto. One of the best guests in this series was former Grambling and AFL star defensive lineman Ernie Ladd, who would go on to a great second career in professional wrestling.

“The Big Cat” spoke about his dislike for playing Namath, but also his respect for the star passer.

“I hated playing Joe Namath,” Ladd said with a roaring laugh. “He got rid of the football so fast you couldn’t influence his throw. You could unload on Namath after the throw, but Joe was tough, and he would trash talk back to you. You rarely saw that from a quarterback, but Joe was not shy about talking back to you. He was pretty damn mouthy, but he could back it up with his play. I had a knack for timing my jump with my long arms and knock down a pass. I was pretty good at it, but Joe was so fast to throw the ball the football would go right around me or between my arms. That had never happened before.

Without Namath in the AFL, we would have had the merger, but it would have been five years later. Some older players were upset when I signed my deal coming out of Grambling and (Billy) Cannon’s deal when he left LSU because we had never played a down in the pros, but this time the Namath deal didn’t upset the players - it upset the NFL owners. Joe Namath was and still is the most gifted passer I’ve ever seen, but his biggest influence for pro football was how we got paid. You would have had to buy 100 big mops to pick up the sweat coming off the NFL owners because of the money Namath got.”

The NFL and AFL had new television contracts in hand, and Joe Namath was the star player the American Football League wanted so much in New York. Dave Dixon spoke to both league commissioners on what the next move was for both the NFL and the AFL, and how it would affect New Orleans.

"I spoke to both Pete Rozelle and Joe Foss, and both assured me that a decision on new teams would be made in 1965, and New Orleans would be heavily in the mix,” Dixon said. “They both said expansion was not a maybe, but a given for the 1966 season. I had pretty good sources that told me that the NFL owners wanted Atlanta first and then us. So Atlanta was the “prime” spot for both leagues, but I felt whichever league didn’t get Atlanta – New Orleans would get the next professional team. I was so confident in early January of 1965 that New Orleans would have a professional football team in 1966. But in reality, 1965 became the most frustrating and disastrous year in the pursuit of a professional team for New Orleans.”