Film Breakdown: Seahawks CB Quinton Dunbar Offers Legitimate All-Pro Upside

Sports are a welcome distraction from the real world for millions around the world. And yet, as we are all painfully aware, in this desperate time of global pandemic, no sport is being played.

Fortunately, Seahawks general manager John Schneider still managed to provide a welcome diversion from the fear and solitude of COVID-19, trading a fifth round pick for Washington cornerback Quinton Dunbar.

Seattle’s pro personnel evaluation department has excelled at identifying defensive back talent that is available via trade and free agency - for cheap too. In the Seahawks’ attempts to replace the "Legion of Boom," the best three results have been NFL veterans.

Justin Coleman was a clear win, arriving for a seventh round pick from the Patriots and leaving for the Lions as the highest-paid nickel in the league. Bradley McDougald was initially signed to a one-year, $2 million contract in 2017. McDougald’s pass coverage dependability has regularly held the back of Seattle’s defense together. He will forever be an underrated Seahawk. Quandre Diggs was rescued from the Lions for a fifth round pick. He immediately brought play making, speed, and a high football IQ to the free safety spot. The last time Seattle had enjoyed this skill set combination at the position, it was thanks to Earl Thomas.

I hear you shrieking that 2017 third round pick Shaquill Griffin has been a success story. However, after three years in the league, the 24-year old still must answer questions in his contract year. Griffin tested as a 96th percentile athlete, yet managed to put on too much weight in the 2018 offseason. He ended that year disappointingly, even before suffering injury. Last season finished with his initially high performance level dipping too. Griffin, in an effort to make plays, blew coverage and cost the team. He was too aggressive.

Tre Flowers aligns opposite Griffin at right cornerback and his playing style is similarly juxtaposed: he must remain cautious. Unlike Griffin, Flowers lacks the agility to break quickly on footballs and make the splashiest plays. Instead, he will win with his length in the first moments. If asked to cover longer, or without the help of a sideline, Flowers will get worked. Nothing demonstrated this more brutally than the exposé unleashed by Devante Adams in the 2019 Divisional Round of the playoffs in a loss to the Packers. Whatever the state of the pass rush, Flowers will often give up the comeback and the underneath stuff. Yet, Flowers’ NFL conversion from safety to outside corner has been okay. With a pass rush, he remains an average cornerback No. 2 who won’t get beat deep.

Seattle's top two corners ended 2019 badly. Yes, the pass rush was an obsolete weapon. However, it can also be true that the coverage was similarly blunt for long periods of the season. When asked about the defensive back play at the NFL Combine, Schneider was candid.

“I mean obviously we want to get better,” Schneider answered. “If I told you that we were satisfied with the performance, I’d be lying.”

At the time of that Indianapolis press conference, the only player on the roster behind Griffin and Flowers was Brian Allen. Allen was a 2017 pick of the Steelers and is a virtual unknown.

Then, the Dunbar move went down. The corner turns 28 in July and is in a contract year looking to earn a big 2021 payday. Having watched his tape, Dunbar has all of the traits to earn significant dollars. It’s remarkable how the former 2015 undrafted free agent out of Florida has developed. Last season, Dunbar was nearing dominance predominantly playing at the right cornerback spot.

Exposure

2019: Week 1 @ Philadelphia Eagles; Week 4 @ New York Giants; Week 5 v New England Patriots; Week 7 v San Francisco 49ers; Week 8 v Minnesota Vikings.

2018: Week 3 v Green Bay Packers; Week 5 @ New Orleans Saints

I decided to skip the 2019 game against the Detroit Lions. Watching Jeff Driskel and being reminded of Thanksgiving sounds like a combo of misery.

Added to the Redskins roster by then-General Manager Scott McCloughan, he of much Seahawks drafting success, Dunbar arrived in the NFL as a wideout. His switch to the other side of the football would happen fast. In August of his rookie year, Dunbar’s career trajectory was transformed.

“My first year coming into the league I was a wide receiver and we were just doing a special team drill, and I was the cornerback at gunner,” Dunbar told the Danny and Gallant show on 710 ESPN Seattle radio. “Guys just couldn’t get off my press and the head coach at the time, Jay Gruden, seen what he liked and then next practice he put me in at one-on-ones and I did pretty good, and it was all she wrote on that.”

Dunbar’s ability to press wide receivers makes sense given his profile. At his pro-day, he measured in at 6-foot, 201 pounds with 32 5/8-inch arms. The Seahawks have never taken an outside cornerback with arms shorter than 32 inches. It’s meme-level of obvious that Seattle loves their outside corners long and tall and Dunbar ticks these boxes. His background and profile screams Seahawks.

There are cautionary examples of veterans who have failed to play with the technique that Seattle asks of their corners though. Expensive free agent addition Cary Williams failed to suitably grasp the step-kick press methodology that the Seahawks coach. Despite having the length, Williams became one of the biggest free agent busts of Schneider’s tenure. He was released from his three-year, $18 million contract, signed in March 2015, in December of the same season. The corner was out of the league after a short end-of-2015 stint in Washington. If there is going to be a complicating factor for a veteran corner in Seattle, it will be grasping the step-kick.

Pete Carroll has said he first saw the technique employed by Raiders legend Willie Brown. There are two footwork elements that Seattle wants. First: the step. A short lateral step with the leverage foot aimed to maintain patience at the line of scrimmage. If aligned on the outside, this is often the outside foot because the corner wants to primarily disrupt the outside release of a go route. The second part of the process is the kick, the kick backwards to stay over the top of the receiver as he runs downfield. This process is unfamiliar for corners who have either been coached to immediately attack with a jab or to fire their feet in a motor-mirror approach. The waiting patience can be a daunting level of calm.

Willie Brown step-kick press at right cornerback. Notice Brown steps with his outside foot first, then opts for the two-hand jam as #81 (Roger Carr?) looks to release vertically through his cylinder.pic.twitter.com/D3pyhT7buG https://t.co/MTjPurHndm

— Under Zone X (Frisco)/Phoenix Check/Stick Slasher2 (@mattyfbrown) April 6, 2020

Kick step, step kick, kick slide. These are often applied to cornerback press. But what does it all mean? This 2011 Iowa State DB clinic from Chris Ash, now Texas DC, explains. This is similar to how the Seattle Seahawks ask their CBs to press transition.https://t.co/brCWUZtVLX pic.twitter.com/0W05Qk6bvY

— Under Zone X (Frisco)/Phoenix Check/Stick Slasher2 (@mattyfbrown) March 30, 2020

Sherman vs Goodwin part 2 pic.twitter.com/X9A0vhznrP

— Eric Crocker 🥷🏾 (@Crocky209) July 29, 2019

“I’m not new to some of the things that they do in Seattle,” a confident Dunbar revealed to 710 ESPN Seattle. “With the step-kick and stuff like that... I’ve worked with coaches who’ve been over there, you know that I knew for a while since I was a kid.”

Specifically, Dunbar credited Marquand Manuel, a former NFL cornerback who spent time with Seattle in Super Bowl XL. His post playing career has involved stints with: Carroll’s Seahawks (2012 assistant special teams coach, 2013 defensive assistant, 2014 assistant secondary coach) and Dan Quinn’s Falcons (2015-2016 secondary coach, 2017-2018 defensive coordinator) He is currently the Philadelphia Eagles defensive backs coach.

Manuel knows how to coach a step-kick. Though he never crossed paths with Dunbar in the NFL, his origins - as a native of Miami, Florida - match Dunbar. Both starred in Florida high school football, playing for teams just three miles apart. Both eventually became Gators. With Manuel 13 years older than Dunbar, it’s possible the senior Florida footballer has taught the junior more than a thing or two over the years.

Dunbar did indeed utilize a step-kick press in NFL games. However, he was more comfortable relying on a soft-shoe approach that saw him step with his inside foot and attempt to mirror receivers more, especially against the better pass-catching talent. It was akin to the “hop-step” that Xavier Rhodes deploys and spoke about in this video. This was effective for Dunbar - whether Seattle allows him to continue to use this technique as his go-to is unknown. Carroll doesn’t feel like a total autocrat when it comes to step-kicking; the bigger issue for Williams was that he kept getting roasted.

Most encouraging - step-kick or soft-shoe - was the patience and diagnosis skills that Dunbar demonstrated in press. He was rarely flat-out beat. Although lacking pure bully upper body strength, he was able to squeeze red lines and flatten routes. His transitions downfield were smooth with fluid hips and an accomplished kick-slide to widen. He was regularly over the top of his man and around the football. In terms of recovery mode, Dunbar had a silky switch-back plus a cut-off move.

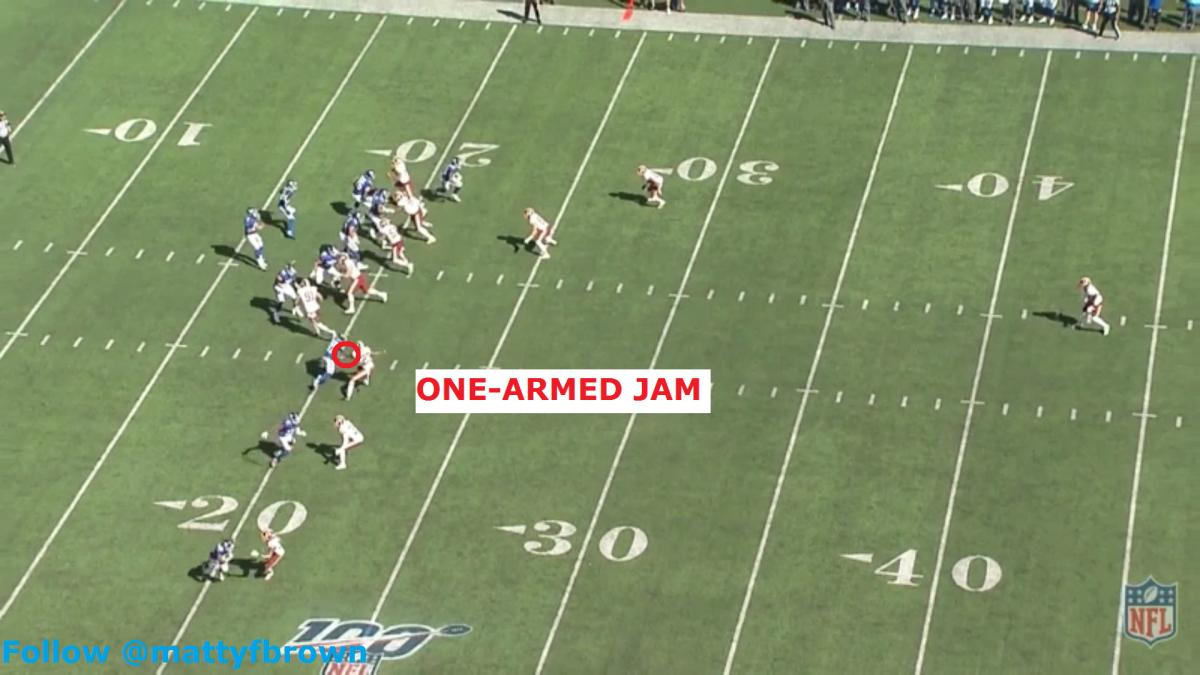

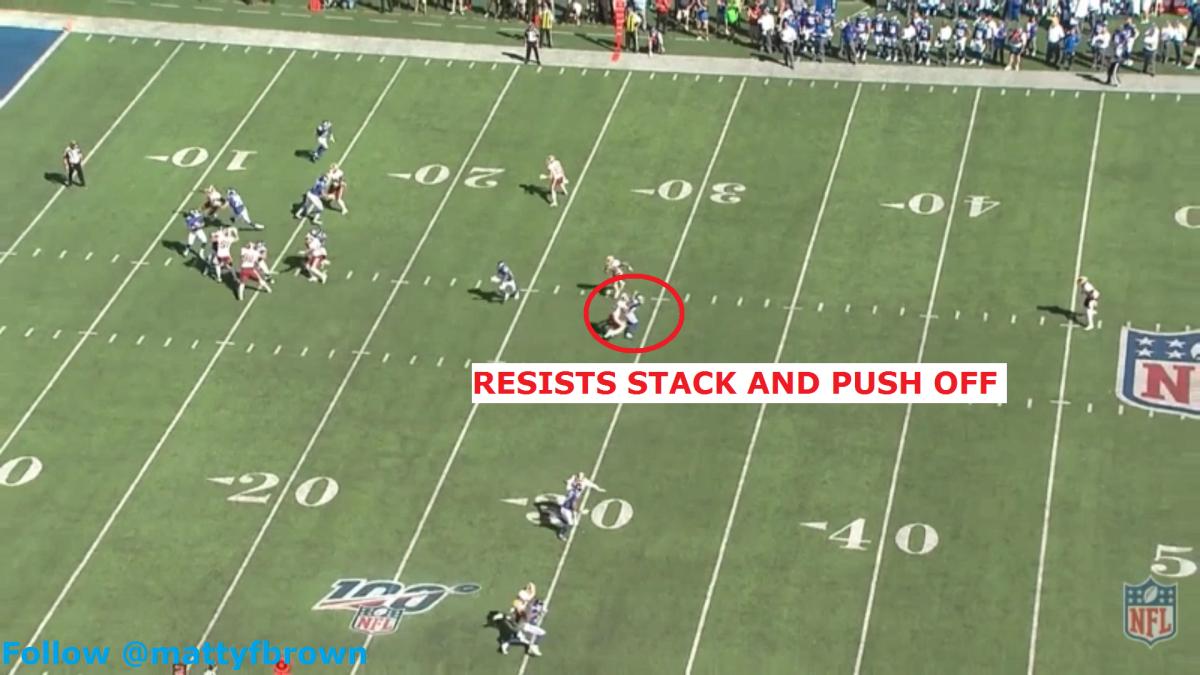

This interception in the slot, with Washington in Cover 1, illustrates the hop-step press. Dunbar was an obstacle for Sterling Shepard.

The corner managed to connect with a one-hand jam while staying light on his feet.

He was resistant to the receiver’s attempts to stack with a bam-step and shove at the route stem.

Dunbar also managed to locate the football and undercut the pass. Ultimately, this rep is illustrative of the man’s ball skills.

Dunbar’s receiver background has massively aided his ability to attack the football. Quarterbacks weren’t afraid of targeting his side of the field, but the corner regularly punished them for it. In 2019, Dunbar caught four interceptions, which was two off the league-high. He added eight pass break ups to that figure. Most impressively, this was despite the cornerback missing five games through injury. This wasn’t just a freaky one-year outlier. Field Gulls’ Alistair Corp wrote: “of the 23 cornerbacks with nine-plus interceptions and 35-plus pass breakups since 2015, Dunbar reached those numbers in the fifth-fewest games and fewest starts.”

On a Seattle team where Carroll constantly emphasizes the importance of turnovers, using the mantra “it's all about the ball,” such skills are invaluable. Dunbar’s game heavily features swag and verve. He flexes big plays. There is a visible confidence and enthusiasm to his play and it’s refreshing.

Take these two examples of Dunbar backed up on his own goal line. Once more, he opted for more of a reflective approach than a pure step-kick. But the diagnosis of a fade route proved correct. Dunbar suffocated the available space for the pass while staying over the top.

He located the football as the receiver did and then attacked the pass with length plus a leap.

Dunbar’s time in Washington placed him in a variety of coverages and techniques. Man-match and zone-match, the defense was complex to the point of assignment confusion. It was terribly abysmal viewing. Dunbar wasn’t though. In Cover 2-style pass defense, Dunbar showcased expert spacing. He was an effective barrier for outside releases when required, he could sink well, and he also excelled with his butt to the sideline, playing from high to low and reading the quarterback’s shoulder.

Seattle does run middle of the field open defense like Cover 2 and Cover 4, but Carroll’s unit is notorious for their usage of Cover 3. What makes this marriage between corner and play caller look so perfect is that Dunbar’s best footage came via Cover 3 assignments.

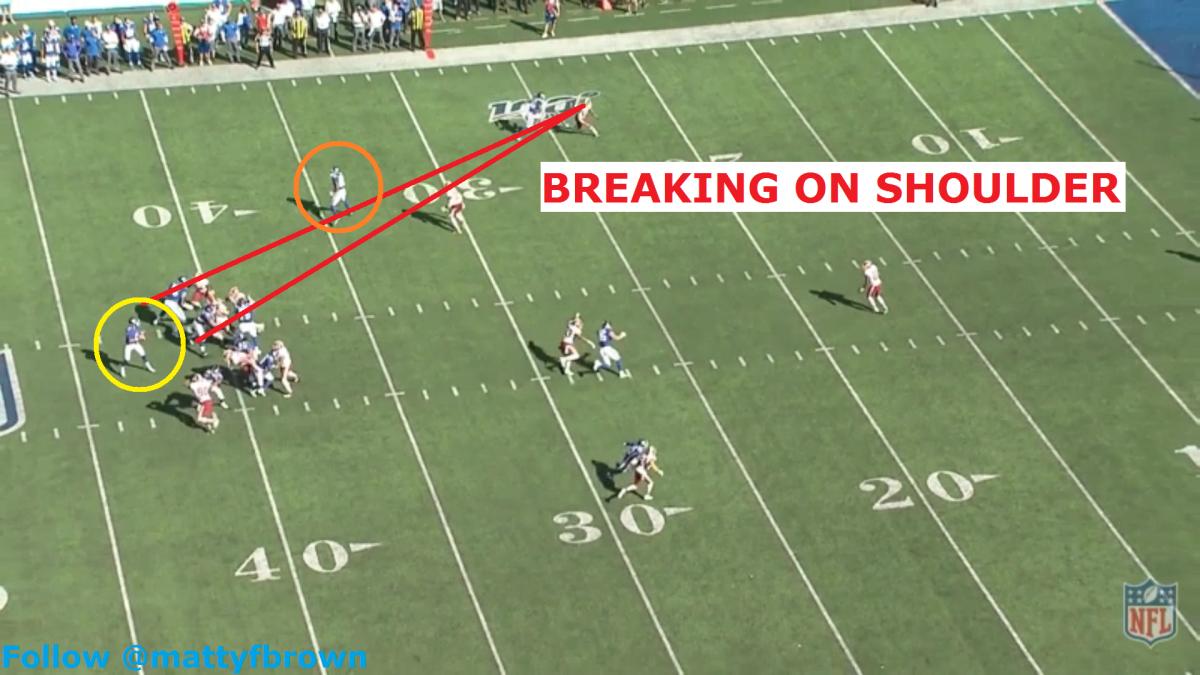

Specifically, Dunbar excels in off coverage. His production on the football comes from him visioning the quarterback in these alignments, with him comfortably reading the triangle of receiver, quarterback, and ball. He is predominantly a reactive corner, but his athleticism -which we’ll get to - and intelligence allows him to still make plays. Furthermore, Dunbar understands where his coverage help is. Due to his comprehension of offensive concepts and his visioning of quarterbacks, he occasionally looks beat on plays because he knows when the ball is designed to come out and whether or not the play is coming his way. Dunbar even remembers the concepts teams are running during the game. Crucially, he gets when to merge on his route and if he can attack the football.

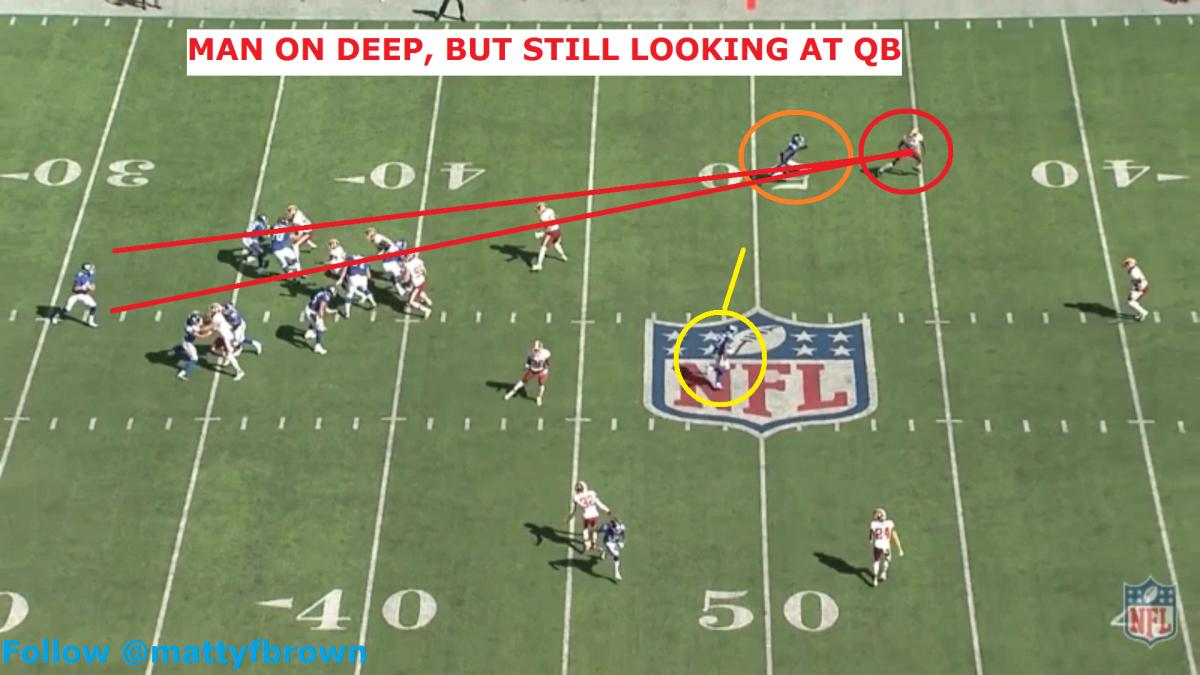

Check out Dunbar in what the Seahawks would call the “1/3 Read” Cover 3 cornerback technique. This involves playing man coverage on a receiver who travels deep into the designated deep 1/3 zone. It’s regularly deployed against single-side receivers. Dunbar was able to do it with a controlled shuffle, slide, or pedal. His velvety hips again aided his ability to transition downfield. His footwork, including a t-step and a drop-step, gave him the ability to break quickly underneath too.

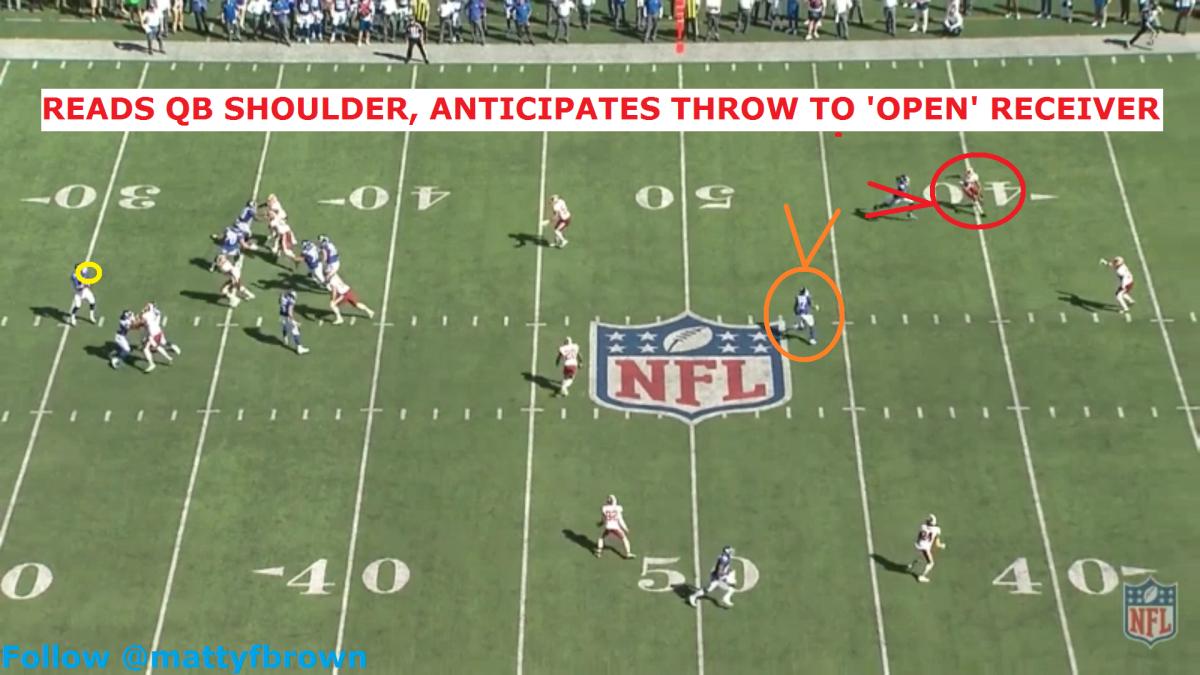

Here Dunbar was over the top of the man directly into his 1/3, playing man on the receiver. He was visioning Daniel Jones though.

The Giants were running a Yankee combination (post-dig) and Dunbar was ready, reading Jones’ shoulder.

Dunbar knew his free safety would take the deeper route and fired at the over route as Jones’ delivered, peeling off his 1/3 Read in front of the intermediate route for the glorious pick.

Dunbar working his Cover 3 zone and technique with the free safety was encouraging, as this was a recurring absence and subsequent issue for the 2019 Seahawks.

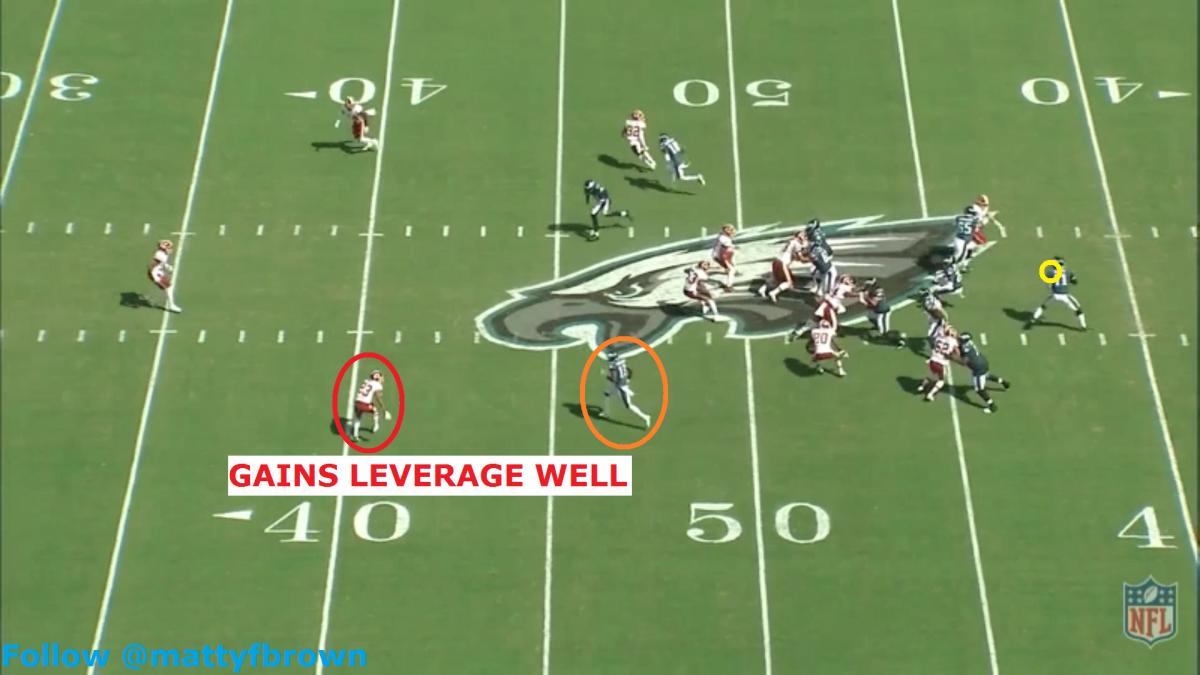

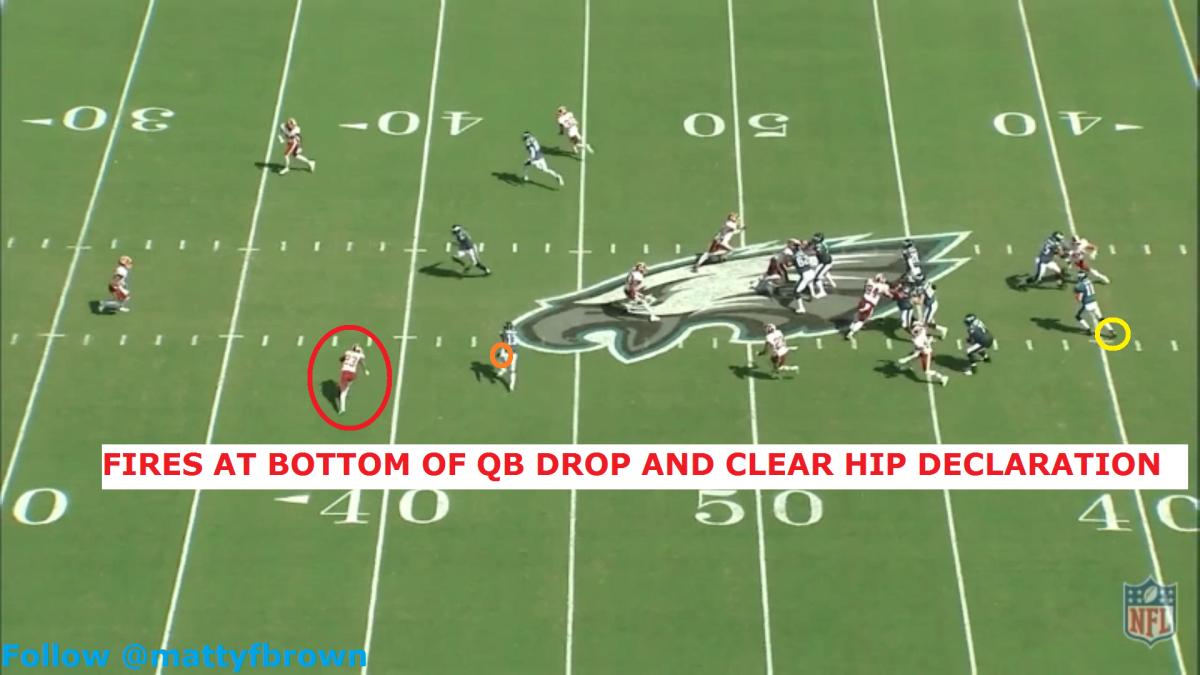

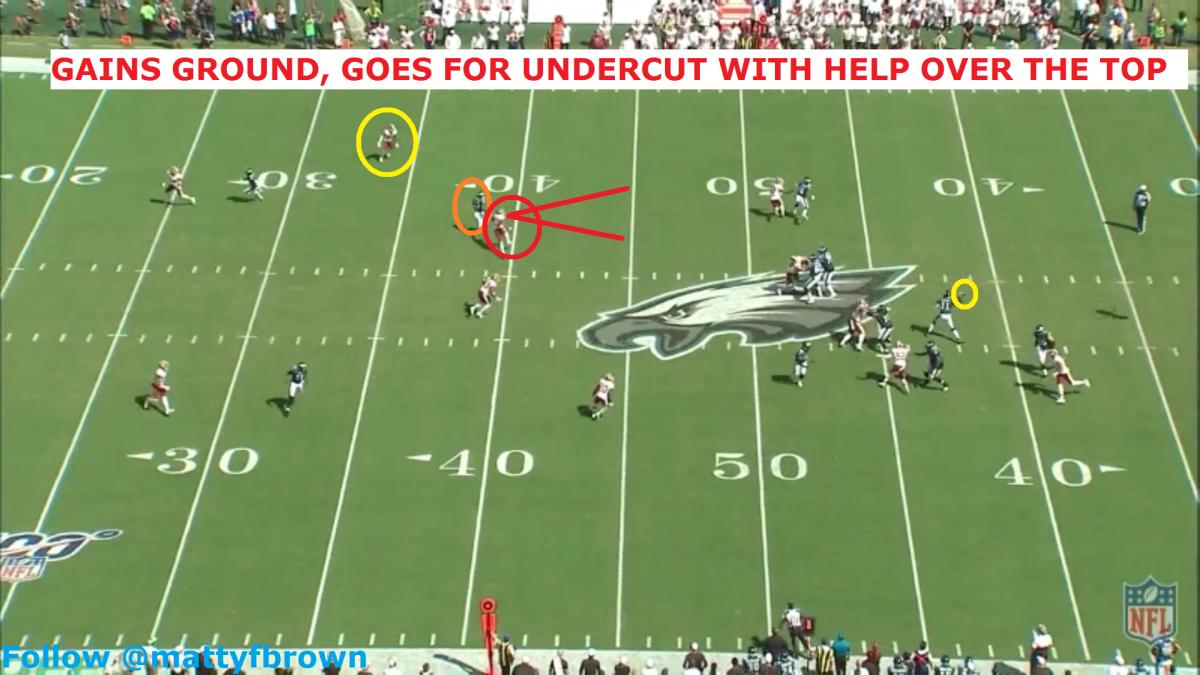

In a 1/3 Read facing the over route, Dunbar held up well too. First, he gained leverage with controlled feet.

Staying over the top of Nelson Agholor while reading Carson Wentz, Dunbar burst well once given clear indicators.

It’s striking that Dunbar was never afraid to make plays on the ball, instead leaning on the inherent confidence that all great play makers have.

If his man went shallow, Dunbar was active and effective in looking for more coverage work. For instance: on the backside of trips.

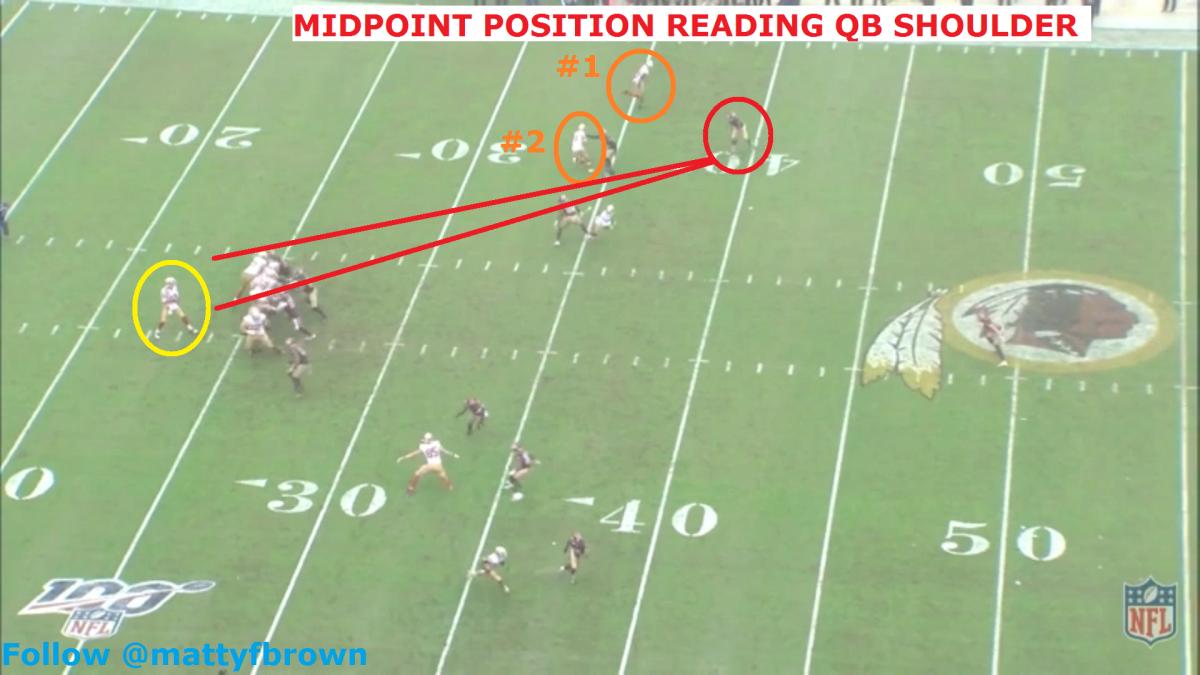

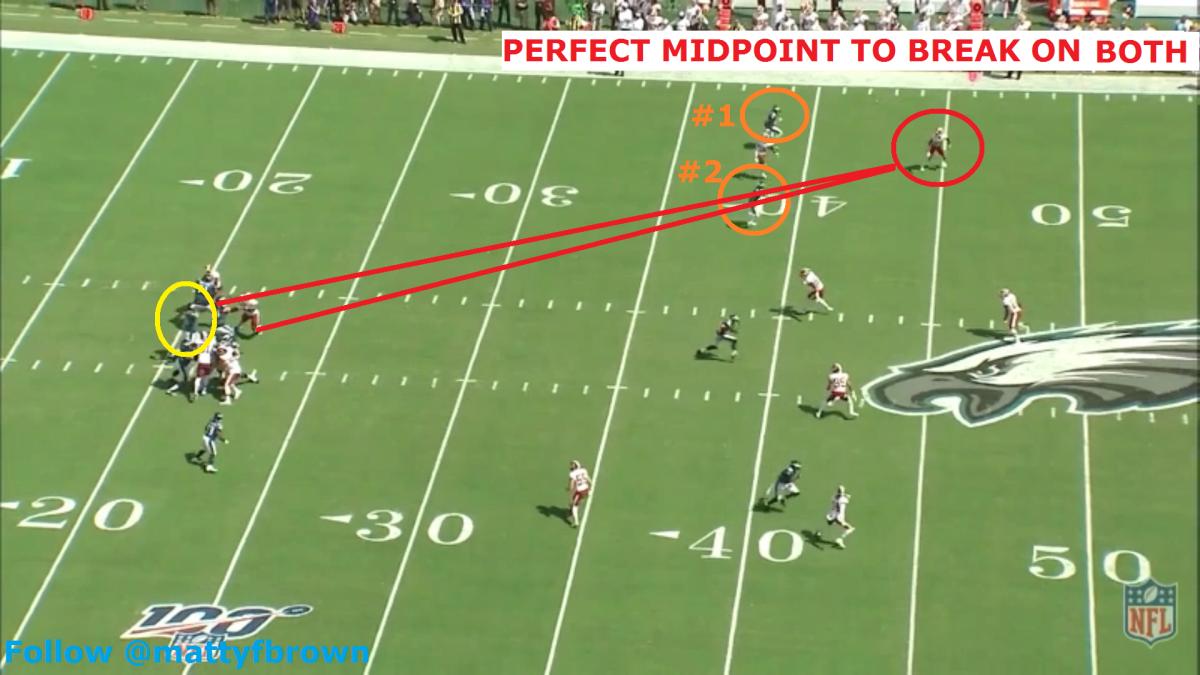

The other Cover 3 technique that the Seahawks ask of their corners is a “Zebra 1/3.” Utilized against two or more receivers, this is a zone midpoint technique that asks the cornerback to dissect two vertical routes downfield into the deep 1/3. Dunbar will do well in this too.

The corner’s positioning was regularly optimal.

Moreover, Dunbar’s breaks were directed at the ball and they were timed impeccably, not arriving too early to be penalized for pass interference or too late while giving up a catch.

Dunbar chose smart technique choices for what offenses were throwing at him. Additionally, he got mad at blown coverages, always ultra aware of the required coverage checks and adjustments. This carries over to Seattle.

As an alternative to their press look, the Seahawks will teach their cornerbacks a press-bail skill that has them up at the line of scrimmage before bailing backwards with outside technique. This enables the corner to disguise their intentions and vision the quarterback afterwards.

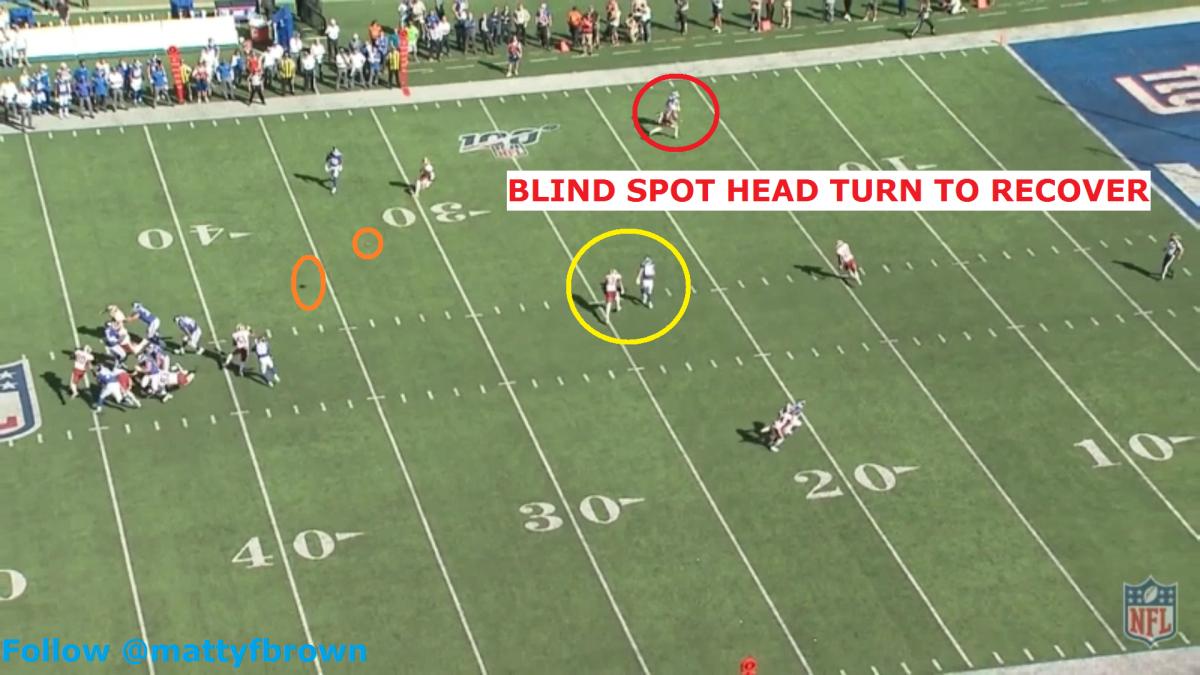

The key for the corner is to get depth rapidly but with control. They must maintain outside and over-the-top leverage, then deal with the consequences if the receiver manages to get in the blind-spot behind them.

On this play, Dunbar anticipated a throw to the flat on what he thought was a curl-flat combo.

Thankfully, the corner didn’t fully break down as he was reading Jones’ shoulder. Dunbar recovered, staying calm to turn his head round and locate the receiver in his blind-spot.

Dunbar was able to stay in phase from his press-bail. The following video features more examples of his press-bail, where he widens in efforts to maintain outside leverage.

Sound leverage is a theme throughout Dunbar’s coverage. The corner pitches his tent. It’s rare that his initial leverage gets broken by a receiver. His off-man, inside defense is a great example of this. He escorted, tempoed, and broke routes.

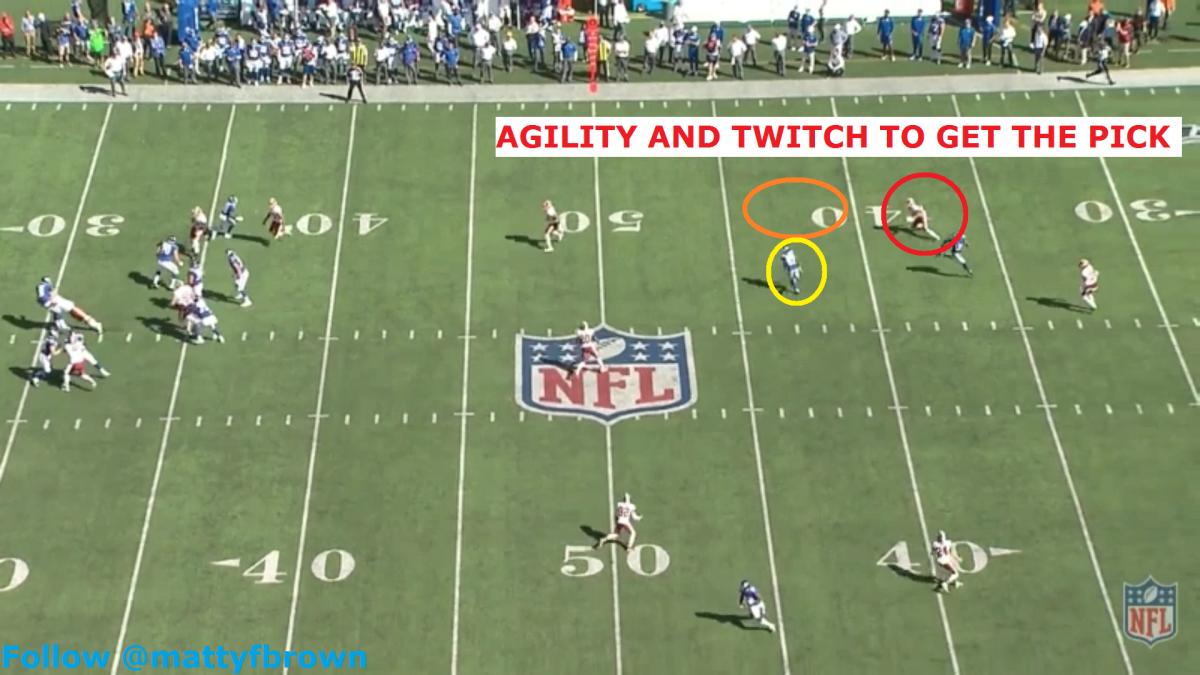

In nearly all of the clips included, Dunbar’s movement skills are obvious. He can lean into his breaks to truly fling himself into the right direction. His pro-day figures according to nfldraftscout.com match the footage. In the summer of 2015, the cornerback ran a 4.44 40-yard dash with a blistering 1.47 second 10-yard split. The couple of plays are full of twitch.

Negatives regarding Dunbar’s game come across as nit-picky. There’s the aforementioned hop-over-step press. In off alignments, dainty, small steps and footwork are occasionally hindered by a false step of hesitation. Against runners, Dunbar overruns plays and disregards the location of pursuit assistance. When meeting these ball carriers, he bends at the waste despite aiming for shoulder contact.

The biggest concern surrounding Dunbar’s game is not skill set-based. Instead, it’s justified doubts over his durability. In his five-year professional career, Dunbar has missed 14 NFL games due to hamstring and leg injuries. He started the first 11 games of 2019 before injury ended his season early.

Still, there is a dearth of attractive draft options with 32-inch arms or longer. I wasn’t enamored with the look of the safety conversion options either. These alternatives would be significant projects for the coaching staff. Dunbar certainly has room to improve (he got better in 2019 from 2018), but he can come in and start from Day 1. The coverage will be boosted. Dunbar has an All-Pro ceiling if he can stay on the field.

What does this mean for nickel? Carroll likes keeping things simple, but we could see different nickel options depending on the opponent. Flowers is suited to taking on tight ends inside. He could get an Akeem King-style role as a bandit back. Shaquill Griffin is naturally the most slot-capable given his athleticism.

At the price Dunbar cost, this was a no-brainer deal for Schneider to make, injury concerns or not. Seattle gave up the No. 162 overall selection of the 2020 NFL Draft. If you recall, that’s the fifth round pick Pittsburgh traded for Nick Vannett - a distinctly mediocre player became something very different. Teams overvalue draft selections and this is a smart gamble. Dunbar has a 2020 cap number under $3.5 million. That’s laughably low. If the corner re-signs elsewhere, it’s likely to come with third-round compensation. That’s the level of player we are talking about here.

This acquisition is what Schneider’s front office seems particularly good at, which is exploiting the foolishness of poor rival decision makers, something he's done in the past to acquire Marshawn Lynch, Chris Clemons, Jadeveon Clowney, and Diggs. Dunbar’s arrival is just the latest example and it could pay major dividends for the Seahawks in the fall if there is a season. Thankfully, his arrival distracted us all from this nasty virus. Stay safe and stay at home!