The red line debate

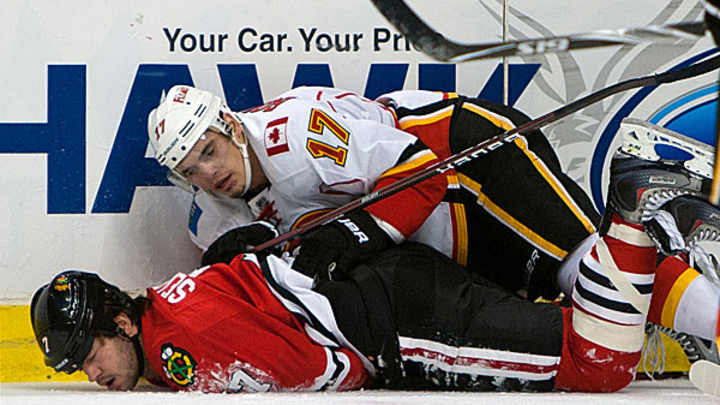

The parade of concussions and players visiting the NHL discipline czar, continued with Rene Bourque (top) plastering Brent Seabrook on Sunday and adding more fuel to the debate about how to stop the carnage. (Charles Cherney/AP)

By Stu Hackel

With concern growing in the hockey world about a spike in concussions during the past few weeks, the wide range of proposed solutions has included restoring the two-line offside pass -- "bringing back the red line," as many hockey people say, although the line hasn't been removed, only the old offside rule that was based on it.

But it's very questionable whether the consequences of restoring it would be worth what might be gained.

"I don’t believe the red line needs to go back in," says NBC's and Sports Illustrated's Pierre McGuire. "It will slow the game down and allow coaches to control the tempo of the game more. And it will lead to more obstruction. You won’t see as many breakaways, you won’t see as many odd-man rushes. You’ll probably have seven to 10 more face-offs per game."

McGuire coached in the NHL and played as a U.S. collegian and a pro in Europe. He's been a keen student of trends in the game and probably has the best seat in the house when he works as a game analyst between the benches on NBC and Versus telecasts.

"If you want to slow the game down, or impede the game, put the red line back in, you’ll see," he says. "The 1-2-2 will be back and bigger than ever. You watch, because you can have a boundary you can use with the red line.

"I think the biggest argument against the red line going back, if there’s a lead established after 40 minutes, and the red line is in, if there’s a two- to three-goal lead, 95 percent of the time, the game’s over, which is not the case now," McGuire explains. "I don’t think, if you’re trying to lure paying customers, you want the last 20 minutes of their experience to be null and void."

The NHL sells speed and physicality and rule changes after the 2004-05 lockout ushered in a new era of both. While studying concussions, the league explained the increased incidents as the unintended consequence of bigger players now traveling at faster speeds, unencumbered by obstruction tactics. The logic of the argument to restore the two-line offside is that since the faster game is being blamed, slowing the pace will automatically decrease the number of concussions.

The post-lockout rules have had opponents, especially among those in the game who prospered during the dead-puck era when the neutral zone was a quagmire of clutching and grabbing, holding and hooking, and an obstacle course of trapping defenders who dumbed down and damaged the product. So it's not surprising that some would want to turn back the clock and use the concussion problem as the justification.

Here's Don Cherry and Ron MacLean on this past weekend's "Coach's Corner" segment of Hockey Night in Canada. They get into it starting around the 4:30 mark, with the red line discussion beginning about a minute later.

And during the second intermission, on the "Hotstove" segment (video), Elliotte Friedman says there could be serious debate at the March GMs meeting about restoring the two-line offside pass. Kevin Paul Dupont in Sunday's Boston Globe reviewed a variety of proposed remedies to the concussion spike and included restoring it.

But McGuire remains unconvinced that this is a practical solution.

"If the red line being out is such a major problem, how come in college -- where the hitting is as ferocious or more ferocious because of heads being used as battering rams because of full face mask -- how come we haven’t had this onrush of concussions at the college level?" he asks. "The red line has been out of the college game forever, since 1979, and we haven’t had this overabundance of head shot issues.

"I think at the end of the day it comes down to respect and, listen, the stakes are greater in pro hockey. It comes down to guys paying attention to where they are on the ice.

"I think the biggest thing is players a still getting used to playing at these tempos and these speeds," he continues. "There’s an adjustment period for everybody. It’s not just because the red line is out. The training has gotten so good, these players are so well-conditioned, they’re so quick and they’re such good athletes. The players are just not used to playing at these tempos. I see it even at youth hockey levels. I’ve never seen it as quick, at any level. I see nine-year-old players skating like 12- and 13 year-old players used to skate. So that carries itself all the way up to the NHL and college."

Other solutions to the problem have been offered and McGuire believes some have merit. He's never been in favor of the trapezoid behind the net that restricts a goalie's ability to play the puck and help defensemen on shoot-ins. That's one issue that many seem to agree would ease the problem.

He also favors the "bear-hug rule" proposed by Toronto GM Brian Burke that would permit a defender to wrap his arms around a puck carrier who is facing the boards. "You’re allowed to wrap up, put him in or ride him into the wall, then release," McGuire explains.

This would be an alternative to defenders who ram the puck carrier from behind head-first into the glass or boards. It has been proposed before by Burke, but has never gotten much traction among other GMs who see it as reintroducing obstruction as well as legitimizing holding. The current emphasis by the league is to approach the puck carrier with less force or from more of an angle, but some players have not yet been able to adjust.

Among other proposed solutions: the NHL has been trying to modify shoulder and elbow pads to make them softer and smaller. That is an ongoing effort. And while many recent concussions were the result of accidental contact, any discussion of effectively deterring blows to the head must include stronger rules against deliberate head contact and stiffer suspensions for violators. That's not the favored approach by the league, the team owners, the GMs, the coaches and the players. None of them want to see skaters taken out of the lineup for extended periods.

The discussion has also turned to making the ice surface bigger, something that McGuire -- who has experience in both NHL and European hockey -- approaches with some caution. He notes in Finland, the rinks have gone to a slightly wider configuration compared to the NHL, but not the full international size of 200 feet by 100 feet. "It would open up more room," he says, "but the bigger you make the ice, the slower the game gets. And if you went 200 by 100, there’d be no hitting."

That may be a moot point. On the "Hotstove" segment linked above, Eric Francis reported that the owners are not in favor of making NHL rinks larger, citing the cost of the transition, which could be as high as $10 million in some rinks, and the lost revenue from the front row of seats.

The ever-lengtheninglist of players who are out of the lineup due to head injuries got a little longer on Sunday when the Flames' Rene Bourque boarded Blackhawks defenseman Brent Seabrook and forced him from the game. That earned Bourque a five-minute major and game misconduct plus a hearing with league disciplinarian Brendan Shanahan on Monday.

Here's that hit.

“When a guy has his back turned and you have more speed than him, it comes down to respect,” Hawks captain Jonathan Toews said. “Headshots and head injuries aren’t going anywhere if we’re going keep making plays like that, and that goes for everybody around the entire league.”

Seabrook has already suffered at least three concussions, two within a short span of the 2009-210 season. UPDATE: Bourque was suspended two games for that hit by the NHL.

The debate on how to limit concussions, accidental and otherwise, will go on for a while but slowing down the game by restoring the two-line pass seems like a counterproductive solution.