Taking the NHL Outside: The making of stadium hockey

Taking the NHL Outside: The making of stadium hockey

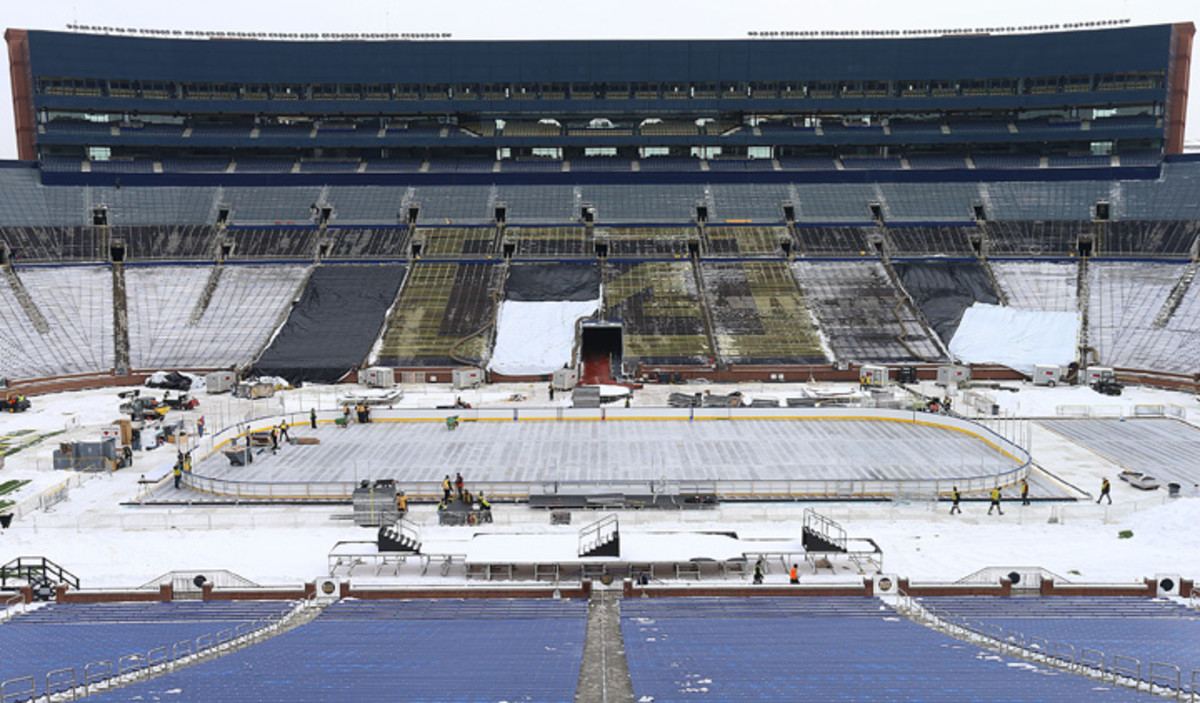

Michigan Stadium, Ann Arbor

Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles

Solder Field, Chicago

Yankee Stadium, New York

By Tim Newcomb

It doesn’t take a meteorologist to know that a sheet of NHL ice outdoors — in stadiums that seat more than 100,000, no less — offers both an aesthetically pleasing visual effect and plenty of challenging weather questions. Just ask NHL ice guru Dan Craig.

The league has expanded its outdoor program from one or two games per year to six across five North American stadiums -- including Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles -- presenting Craig with his biggest and most difficult job yet. The scariest part? All of his efforts in the widely varying locales will be at the mercy of the elements, which will ultimately determine the final quality of the ice.

GALLERY: The NHL's Outdoor Games

The 2014 outdoor series begins with the Maple Leafs against the Red Wings at Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor on Jan. 1. Craig tells Sports Illustrated that he’s hoping for a “party house,” and he may get one. “Michigan, because it is the Big House, it will be absolutely amazing to stand out on that field and have 110,000 screaming fans,” he says. “I can’t imagine that, as a hockey player. They will get jacked right up.”

After the cold of Michigan, the NHL will head to Los Angeles, putting an ice rink amidst the palm trees in Chavez Ravine for the game between the Kings and the Ducks at Dodger Stadium on Jan. 25. To counteract the affects of the Southern California heat -- the puck is scheduled to drop at 6:30 p.m. PT -- thermal blankets will be laid over the entire sheet of ice during the day to keep the sun off the surface.

There are two more games in January — the Rangers play twice at Yankee Stadium, against the Devils on the 26th, and against the Islanders on the 29th — followed by a March 1 game between the Penguins and the Blackhawks at Chicago’s Soldier Field. The Senators play the Canucks at Vancouver’s BC Place on March 2.

What does Craig hope for in all these scenarios? Forty-five degrees Fahrenheit and overcast skies. “If I get rain it is going to be a challenge,” he says about the potential for puddles and soggy ice. “Bright sunshine is a challenge.” Bright sun not only degrades ice, but it also affects players' ability to see.

Before dealing with game-day weather worries, however, Craig’s team needs to actually build outdoor rinks in the middle of stadiums. Football fields are crowned and baseball diamonds can slope. To improve sightlines in MLB venues for spectators, the rink stretches from first base to third. In football stadiums, it sits dead center on the fields. Any slopes — such as the six-inch drop from first to third at Wrigley Field in 2009 — are offset by building up the rink’s subfloor.

After the subfloor is built, 243 ice tray panels, each 28.5-feet-long by 30-inches-wide, go under the ice. The panels have a loop of 3,000 gallons of glycol coolant constantly running to keep the ice a perfect 22 degrees Fahrenheit. The coolant also flows through a mobile rink-refrigeration device -- a 53-foot-long, 300-ton unit, located on site. The NHL rolled out its second of these in December to handle the Michigan, L.A. and Vancouver games.

To create the ice, Craig’s team spends up to 10 days misting 20,000 gallons of city tap water until it becomes a two-inch thick sheet, which is nearly a full inch thicker than a sheet in an indoor arena to allow for weather-related evaporation. Craig uses thermal blankets near the sideboards, where sun glare can warm the ice, to keep it fresh for the game.

About 350 gallons of water-soluble paint keeps the surface of the sheet white, and Craig embeds 16 Eye on the Ice sensors to provide real-time data about ice conditions. But even with all of the high-tech monitoring and planning, there’s still one thing that could potentially cut the league's planned six outdoor games down to five: Vancouver's BC Place has a facility rule — which supersedes any NHL wishes — requiring the retractable roof to be closed during rain to protect the stadium’s interior.

It's safe to say that, whether it's a roof closure or wishy-washy ice outside, the NHL isn’t a fan of precipitation.

You can check out an illustrated account of the stadium plans in the Dec. 30 edition of SI magazine.

Tim Newcomb covers stadiums, design and technology for Sports Illustrated. Follow him on Twitter at @tdnewcomb.