Fancystats quietly leading NHL teams to dump the dump-and-chase strategy

Advanced analytics converted the Minnesota Wild to believers in puck possession. (Bruce Kluckholn/Getty Images)

By Sam Page

On the rush, the Wild forwards have numbers, but no structure. Captain Mikko Koivu carries the puck, skating along the right boards in Chicago's United Center nearly side-by-side with winger Zach Parise, who is on his left. Blackhawks defenseman Michal Rozsival, seeing the awkwardly bunched pair, comes out to the blueline to kill two birds with one check.

It’s October 26, just the fourth week of the new season, and Minnesota leads Chicago 4-2 with 4:27 remaining in the game. As recently as last May, the last time he played against the Wild, Rozsival’s gambit would have been a good one. Safe hockey dictates that Koivu ram the puck along the boards, eliminating a possible turnover. It’s the ultimate dump-and-chase situation, and Minnesota has been the ultimate dump-and-chase team since the inception of the franchise in 2000.

When Mike Yeo was hired to coach the Wild in 2011, he had good reasons for sticking with such a strategy. His previous NHL job had been as an assistant coach on a Pittsburgh Penguins team that had won the Stanley Cup in 2009 preaching the importance of, in his words, “getting pucks deep.” And in Minnesota, Yeo had inherited a roster of rambunctious players who were just fine with a game plan that dictated footraces to the endboards.

For a long time, NHL coaches have seen the chip-and-chase strategy as a viable alternative -- even an antidote -- to the puck possession game played by the league’s best clubs, e.g. the Blackhawks and the team they are modeled after, the Detroit Red Wings.

But hockey’s version of the sabermetrics movement has shown the dump-and-chase maxim to be the natural analogue to baseball’s devotion to the sacrifice bunt -- a needless waste of the game’s most precious commodity (possessions in hockey; outs in baseball) for a small benefit. More than ever before, winning in today’s NHL means holding on to the puck.

Koivu barrels through Rozsival, who crashes into the boards. Even with Chicago's Jonathan Toews backchecking, the Wild retain their man advantage. Blackhawks defenseman Duncan Keith retreats to cover Parise, and Toews sticks with Koivu, who circles behind the net and flips the puck out in front to unguarded rookie Justin Fontaine, who raps it past goalie Corey Crawford.

The goal seals the win in Minnesota's return to the United Center five months after the Blackhawks had unceremoniously dispatched the Wild in the first round of the playoffs with a 5-1 drubbing in Game 5. That loss spurred Yeo toward the changes that would make goals like Koivu’s possible.

“We felt that there were many aspects of our game that when we matched up against Chicago, we were right there with them,” Yeo said. “We knew that if we were going to take another step as an organization, we were going to have to become better offensively.”

So in a total departure from the strategy the coach once adhered to so faithfully that some Wild fans began referring to it as “The Church of Yeo,” Minnesota entered this season emphasizing the controlled zone entry, i.e. skating into the offensive zone with the puck. If it works -- the Wild are 25-19-5 as of this writing, holding on to the eighth and last playoff spot in the rugged Western Conference -- hockey may more quickly realize an advanced stats revolution of its own, thanks to the unlikeliest of marriages: bloggers and the team they once loved to hate.

Getting the word out

Eric Tulsky’s message finally reached some of the people who most needed to hear it. At the 2013 MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in Boston -- the mere existence of the annual March event is a sure sign that the statistical revolution in global sports has gone post-punk -- the soft-spoken Tulsky explained his radical ideas on the importance of puck possession to front office executives of the Wild, the Stars and the Capitals.

After speaking for 30 minutes to an hour with each team, Tulsky sensed genuine interest in his findings. But for months after the conference, no one called him back. He assumed his ideas had been forgotten -- or worse, had been dismissed -- until he read his Twitter timeline:

@BSH_EricT @mc79hockey i don't know if someone clued trotz in on this one, but he's been pushing carry-ins in camp. ...

— J.R. Lind (@jrlind) September 15, 2013

Q and A with #mnwild coach Mike Yeo: "We're going to be more aggressive." http://t.co/LHGVzMldBM

— Michael Russo (@RussoHockey) September 8, 2013

Sat in on video session at #CapsCon. #caps have most extensive collection of #Fancystats I've seen, incl zone time and entries by line/dpair

— Neil Greenberg (@ngreenberg) September 21, 2013

“It seems unlikely that that's just a coincidence,” Tulsky said.

Eric Tulsky (Courtesy of Sloan Sports Analytics)

Tulsky, 38, works at an energy storage start-up in Silicon Valley. He boasts degrees in physics and chemistry from Harvard, and a PhD in chemistry from Berkeley. A Philadelphia native, he got into hockey analytics on a lark in 2010 while writing for a Flyers fan blog, Broad Street Hockey.

Three years later, he arrived at the Sloan conference to promote his paper, “Using Zone Entry Data To Separate Offensive, Neutral, And Defensive Zone Performance.” The study’s conclusion is counterintuitive: “It is found that talent for driving shot differential derives almost entirely from neutral zone play and that attack zone talent is largely confined to shot quality effects.”

Basically: While one defensive zone blooper or offensive zone dangle may win the day, the difference between the best and worst teams is how well they move the puck through the neutral zone.

Tulsky found that players who carry the puck across the blue line produce twice as much offense as those who dump and chase. His research elevates carrying the puck successfully through the neutral zone from something the best players and teams do to an object of the game.

Fenwick Close -- by consensus the best measure of possession -- is expressed as the percentage of total shots that a team takes during tightly contested play. According to habseyesontheprize.com, teams that eclipse the 50% mark make the playoffs 75% of the time.

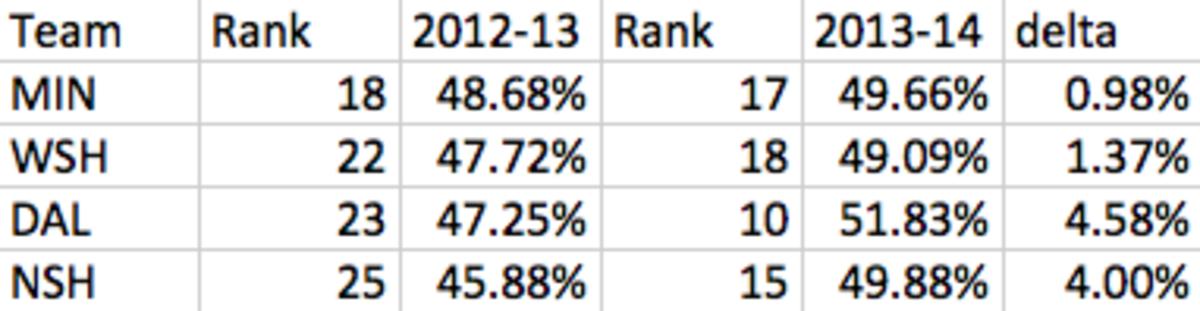

This season, Tulsky's guinea-pig teams are all nearly hitting that "magic" 50% a year after failing to do so:

In the standings, the two teams that have transformed their games the most -- Dallas (21-18-7) and Nashville (20-21-7), 10th and 11th, respectively, in the West -- are long shots to make the playoffs, victims of poor defense (Stars) and substandard goaltending (Predators), and the best conference in the league. In the much weaker East, Washington (22-16-8, 5th in the conference) has a good shot at the postseason.

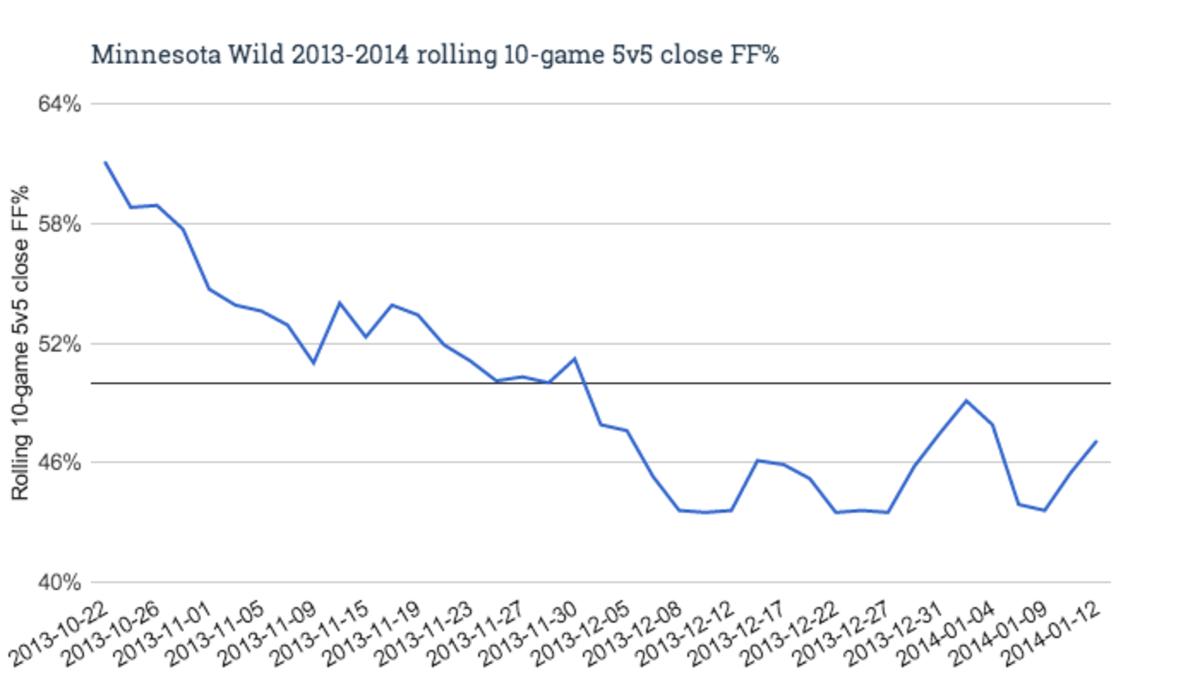

It's the least-improved team, the Wild, that currently has the most points, with 55. But that number undersells their season to date. While Dallas, Nashville and Washington have all hovered around 50% FenClose all season, Minnesota has been more up and down, getting off to a hot start (15-5-4 through Nov. 23), enduring a rapid descent (5-12-1 from Nov. 25 through Dec. 31), and making a subsequent recovery (5-2 in January):

(via extraskater.com)

More significantly, the Wild themselves attribute their hot streaks to their zone entry game, while they cite their low point as a time when they were doing too much dumping and chasing. In fact, when you unpack how each of the four teams in question reached this point, Minnesota may well be Tulsky's most fervent convert.

Nashville was the first team to employ Tulsky, during the 2012 offseason, after Paul Richard Cook, the Predators' executive assistant for hockey operations, recognized the analyst's name in one of the many unsolicited emails that Tulsky sends out to NHL teams. Hired by Nashville as a consultant, Tulsky filed advanced scouting reports of sorts for the coaching staff and got enough feedback to believe that his work was being carefully considered.

Still, in spite of the Predators' improved possession numbers, Tulsky's influence has limits. (“We’re not making decisions based on any stat,” said Nashville general manager David Poile, referring to the subject of player acquisition.) The relationship between the analyst and the team is less Billy Beane throwing a chair through the coach’s window than it is Paul DePodesta (or if you saw the movie, Peter Brand) slipping a memo under the coach’s door.

In Dallas, Frank Provenzano, the assistant GM who spoke to Tulsky at Sloan and had started tinkering with tracking zone entries, left the Stars this summer when Jim Nill, the former assistant GM in Detroit, replaced Joe Nieuwendyk as general manager.

Ironically, though Nill subsequently purged all things analytic in favor of the Red Wings model, similar statistics still caught hold. Puck possession, statistically measured or not, has always been a hallmark of the Detroit game, so it was no accident that Nill hired Lindy Ruff, a coach who has an affinity for possession hockey. Indeed, the former Sabres coach was already tracking his own zone entry stat, one based on the number of failed entries a team makes.

But it is the Wild's transformation that, in some ways, has been the most complete.

“This was going to be a year that there was a focus on entering the zone with possession and helping us get on the offense through puck possession,” said Minnesota forward Matt Cooke, who played for Yeo in Pittsburgh before signing with the Wild this season.

The secret formula

The Wild won’t discuss to what extent, if any, Tulsky’s work has played in their transformation. Minnesota's front office declined all interview requests, including specific questions about the organization's use of statistical analysis.

Yeo admitted that Minnesota tracks zone entries for every game. While he characterizes the front office’s role in the style change as more supportive than formative, it's clear that Tulsky’s work has enabled that support.

It's not as though the benefits of the puck-possession game were a secret. “If you did stats on every one of the games in the first seven or eight years that we played the Detroit Red Wings, I’m ninety-nine percent sure that their puck possession was more than ours,” said Poile. “We weren’t trying to let them do that -- they were a better team.”

And the Wild have also become a better team. They famously signed Ryan Suter and Zach Parise to 13-year, $98 million deals before the 2012-13 season. But while personnel is important, playing with the puck is far more of a choice than most teams acknowledge. And the impetus for too often making the wrong choice -- fear of a disastrous turnover -- is drastically overrated according to Tulsky’s work.

“We recorded for two years every time an entry was on an odd-man rush,” Tulsky said. “I could look at every time you had a failed entry: How often does that lead to an odd-man rush the other way? And it's much more rare than people think.”

Still, while rare, the downside of the puck-possession game can be discouraging, and Minnesota's players believe it has contributed to their streakiness this season. A few goals-against on defensive breakdowns speak louder than a bevy of shots when the shots aren’t going in.

As recently as Nov. 14, the Wild’s possession game was humming. Their FenClose ranked fourth in the NHL at 57%, their 7.6% improvement over the previous season was the best since the stat started being tracked in 2007.

But during four straight hard-luck losses at the end of November, the Wild outshot their opponents 130-108 while being outscored 8-3. They subsequently strayed from their breakout game, getting outshot 381-339 in December, to predictable results.

“We're getting away from it now, because we're not having as much success, not scoring a lot of goals,” Suter said after a 5-2 loss to the Penguins on Dec. 19. “You have to be a confident group to make those plays. And I think we're getting away from it now because we're not confident.”

Still, Yeo kept the faith, re-emphasizing to his players the idea that a good process will eventually yield a good result, even if it seems impossible in the short term.

“We do know that we're getting the shots, we're getting the chances, and that if we continue with the process, it'll come,” Yeo said.

This doubling-down on the possession game represents an interesting 180 from Minnesota’s position two years ago. Thirty games into the 2011-2012 season, the Wild had the most points of any team in the league. Yet they boasted the worst possession stats in hockey. Stats bloggers, Tulsky’s consultancy partner Derek Zona chief among them, made Minnesota a test case for the importance of puck possession.

The Wild -- somewhat miraculously given their head start -- missed the playoffs by 14 points that year. The Kings, statistical darlings championed by Tulsky and others, won the Stanley Cup. Underscoring the irony: Minnesota had been cited in Tulsky’s original study as a textbook example of how a team should not play.

Now the Wild are being rewarded for putting their faith in a good process. And while their FenClose doesn't scream "Stanley Cup contender" like L.A.'s did a few seasons ago, their conscious belief that they can improve their shot differential with on-ice adjustments makes them an interesting team to watch nonetheless.

“We got the green light to try to skate in with the puck and make more plays,” winger Jason Pominville said. “And it lead to us having the puck a little more in the offensive zone and creating a little more, especially early on in the season -- we were outshooting teams by big margins.”

Statistically-inclined fans waited for the Maple Leafs' inevitable collapse this season as a proving moment for the predictive and explanatory powers of shot-based metrics. In many ways, though, Minnesota, if it continues to have success, represents a more important test case.

The push for the use of advanced statistics has always been about sacrificing small, obvious gains for bigger, though sometimes imperceptible, advantages. The Wild, faced with a tailspin, forsook a familiar strategy and reaffirmed their faith in a scientific solution.