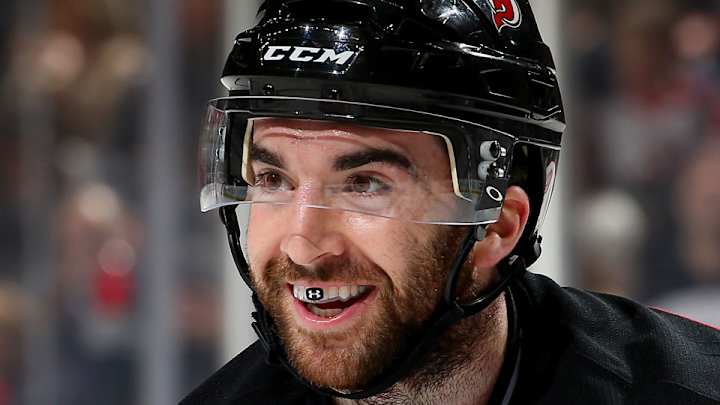

Jersey Boy Kyle Palmieri giving Devils his best in homecoming

Kyle Palmieri likes his sandwiches with roasted red peppers and fresh “mutz”—like any good Jersey Boy. So much so that he brags to his dad, Bruce, whenever he gets the chance to chomp down on one. Bruce is always jealous.

Kyle, 24, loves his Italian food—and he’s Jersey through and through. High school in Jersey City at St. Peter’s Prep. Slices of pizza at Benny’s in Hoboken, where his picture hangs on the wall. Hours and hours of skating in his hometown of Montvale.

Now he's back home after a detour of eight years through Michigan and Indiana, Syracuse and Anaheim. He’s back where it all started, with the team of his youth—the one that named him High School Player of the Month, the one that used to practice in West Orange as Kyle looked on.

What we’ve learned about Eastern Conference teams at midseason

And now his parents, Bruce and Tammy, are the Devils' newest and biggest fans, with season tickets in section 13 of the Prudential Center, nervously cheering for their boy as his career takes off in the state they love.

On a cool Saturday evening in December, Bruce and Tammy take their seats behind the Devils net, a section up, on the aisle before a game against the Ducks, Kyle’s former team. Tammy is decked in a Palmieri jersey. Bruce is wearing a Devils warmup jacket, his season pass as a guest proudly displayed on his chest.

The Palmieris are nervous watching Kyle. Always have been. Like when he was a kid in Jersey City. Or when he was 3,000 miles away in Anaheim and Grandma made sure to stay up past 1 in the morning to watch every game, no exceptions. It’s gotten easier, but only slightly. They know the risks. They know the sport is dangerous, and there are plenty of times when they cringe. They know Kyle likes to go in front of the net, because that's what Bruce taught him to do—don’t be a pretty boy. Go to the net.

They know what they instilled in Kyle. They know that he was born with a drive, a work ethic.

When Kyle was six, he wrote down what he wanted to be when he grew up. Most every kid chooses something unattainable—astronaut, president. Kyle wrote down hockey player. The Palmieris have it framed in their house, still there 18 years later.

Bruce says it remains because they're bad at taking stuff down. Tammy shakes her head.

"It'll be there forever,” she says.

NHL Roundtable: Jones-Johansen trade winner; first half MVP; more

Back when he was 10, and Bruce was his coach, and Kyle was the team’s best player, dad wouldn’t give him the C, even though he deserved it. And he tried talking to Kyle, tried talking to his 10-year-old like a man. You don’t need the C to lead, Bruce said. Lead by example. Lead with your heart, lead with your feet, lead by being you.

The Devils were sloppy in their first period matchup against Anaheim, and the Ducks quickly jump to a 1–0 lead. When Kyle gets the puck at the blue line, he immediately bumps into the ref. “C'mon!” Bruce yells as the puck slides away. “Could’ve had something there.”

Tammy watches the game as a bundle of nerves. It was toughest for her when Kyle was selected to go to the U.S. National Development Team, to send her boy off to Ann Arbor. At tryouts, Bruce looked on and was unsure. Tam, he said, everybody here is good.

Kyle, after making the team, called Bruce. I’m on the fourth line, dad. What do I do?

What do you want me to do? Bruce replied in his thick Long Island accent. Work.

So Kyle did. Moved up to the first line. Moved up to the U-18 team. Moved on to Notre Dame and to the AHL and now the NHL, a place he and his family thought he could end up, but weren’t really sure.

As the action against the Ducks continued, Tammy crossed her hands, elbows on her knees. When Kyle got the puck and she popped up, elbow at attention, bouncing like the disc had been doing all night for the Devils.

The Ducks scored again right before the end of the period, and boos began to rain from the crowd. The Palmieris didn’t start out as Devils fans, but they are now. When former teammate Ryan Kesler scored that second goal for Anaheim, they groaned and jumped back in their seats. Silence.

Captain Andy Greene is the Devils' steadying force in season of change

It’s weird seeing Anaheim, Bruce says. He remembers being on the annual “dads” trip with the team and loving it. It’s been weird for Kyle, too. There’s more media attention before this game, seeing old friends and coaches for a team that came so close to making a Cup run.

Kyle loved Anaheim. So did Bruce and Tammy. The Ducks gave him his start in the NHL, after all, drafting him 26th in the first round of 2009. But it was tough to get playing time behind names like Getzlaf and Perry and Kesler, Selanne, Koivu and Ryan. So when he was traded to New Jersey last June for two draft picks, the Palmieris were excited but also disappointed for their son. They knew Kyle had made a bunch of friends in Southern California. They knew the players, the coaches.

But they also knew something only parents could: New Jersey was going to get the full Kyle.

What type of player do you want to be? That’s what Bruce asked when Kyle first made the NHL. Who do you want to be?

I want to make an impact, Kyle told him.

And that’s what Kyle has done this season, becoming one of the pleasant surprises for a team that was expected to scrape for goals. He has a career-high 17 thus far. He'll reach career bests in every meaningful statistical category this season. It's a true Jersey homecoming, Bruce says. But not so much for Kyle. He focuses on his job. He’ll only visit with friends after a game if there’s nothing to do the next day. He'll come home occasionally, but only on full off days. And the last time he tried, Bruce and Tammy were working, so he stayed back in his apartment in Hoboken, overlooking the Hudson River. Friends, family members ask him for tickets. Kyle knows how to stay no, because something bigger is at stake.

Who deserves an All-Star Game spot from the Atlantic and Metro Divisions

It’s been that way since he was a kid. Kyle would be out on the family rink that Bruce built, for hours and hours. He woke Bruce and Tammy up so he could be driven to hockey practice. He played during his summers, any chance he could get.

Bruce is a coach. He has seen what familial pressure can do to a player and he wasn’t about to have that kind of negative influence on his son. All he wanted was for Kyle to have fun. Every effort came from Kyle—the hours on the rink; the move to Michigan for the US National Team. It was Kyle who, at 19, came to Bruce and said he was ready to leave Notre Dame and go pro, ready to make a full commitment to the sport he loves.

It came from within then and it comes from within now, as he gains his footing as a key member of a team on the rise.

“Is it a hard 10:10 departure?” Kyle asks a public relations official as he scoots through the bowels of the Prudential Center after the game, clad in an expensive suit with the collar undone and sky blue socks poking out from his shoes.

The Devils, having lost the game, 2–1, are about to depart for Boston for a battle with the Bruins the next night. Palmieri, though, needs to make one more stop.

So he walks briskly down the corridors, makes a right at the practice rink, and waits at an elevator bank. Eleven people bolt out of the elevator. There’s Bruce and Tammy and Kyle’s sister Tahrin. Kyle’s girlfriend is there, along with friends from the neighborhood. There are hugs, kisses, good wishes expressed.

Kyle hustles back to the team bus, leaving a gaggle of Palmieri supporters in a cluster by the door.