‘Would you like to get beaten up by Gordie Howe?’: A remembrance

Your teams. Your favorite writers. Wherever you want them. Personalize SI with our new App. Install on iOS (iOS or Android).

Man, you don’t get an offer like that every day.

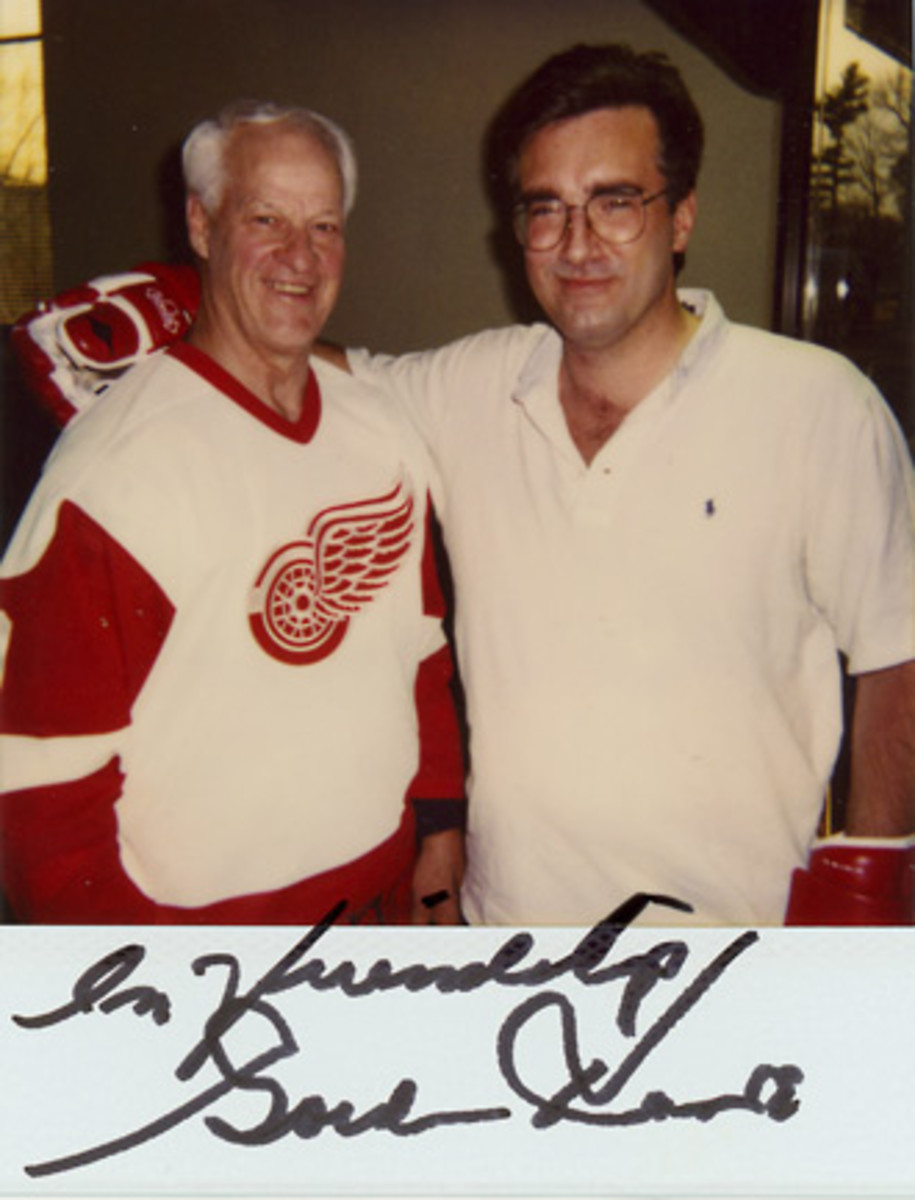

I was 37 and he was 68 and they promised he’d pull his punches so it would almost be a fair fight and my arms and hands would only be numb for about an hour after he left and most importantly: He’d be happy to take photos with me.

So I got beaten up by Gordie Howe. And between takes of the commercial he let me wear his gloves, and I became part of what is, for all I know, a majority of North America’s population: people who had their photos taken with him.

He never stopped taking photos with fans nor signing autographs for them. And let’s be clear, he wasn’t a saint about this: he made a nice living off beingGordie Howe and under the strategic brilliance of his wife Colleen (who might have been a tougher businesswoman than he was a tough player) they got trademarks not just for the nickname “Mr. Hockey” but on “Mrs. Hockey” as well.

He sold photographs and autographs to the businessmen and the memorabilia entrepreneurs. They would pay him to show up. And the fans might buy a signed stick or a puck or a jersey or if somebody made them, replica bumpers from the 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder that Cameron Frye destroyed in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Gordie Howe, man of the people: my treasured moments

But an autograph on something you had with him? Or a photo? Gordie Howe insisted he never took money directly from a fan. And behind it was a specific story.

Twenty-five years ago my friend Tim Kiely, who now produces the NBA on TNT, was working with Howe on a long-forgotten all-sports network called SNN and he saw the endless flow from Howe’s pen and the constant pre-selfie ritual of the ask, the pose, the camera not working, the photographee trying to explain to the photographer which button to push, the nuclear-quality flash and then the handshake.

He asked Howe if he ever got tired of it.

“No, sir,” Kiely recalls Howe telling him. “And I never take money and let me tell you why. I was walking on the beach in Florida with my grandkids and a guy comes up to me with his son and says to him ‘This is the man who saved my life.’”

Howe stood in astonishment as the man explained. He had been a Detroit kid, sent to pilot missions in the Korean war. After he was shot down, he returned to Detroit and given little chance to survive, his family grasped at every straw it could. It contacted the Red Wings and asked if Howe could sign something “just for luck” and send it to the hospital. Instead, Howe told Kiely, he delivered the autograph personally, and obviously the pilot recovered.

“And that’swhy I don’t mind, and I don’t take money.”

Former NHL goalie-now TV analyst Corey Hirsch tweeted on Friday that he went to his first game, Whalers vs. Kings in Los Angeles, at the age of seven and was confused by something he saw on the ice just before the game began: why “everyone was crowding around that player.” It was Howe, warmup skate over, signing autographs—Hirsch guesses at least 200—over and around the glass. In another team’s building.

'Mr. Hockey' Gordie Howe—NHL Hall of Famer, Red Wings legend—dead at 88

There are sports icons—DiMaggio, Jordan most of the time, Jeter, often—who are remote and unreachable and project a force field of brilliance that both stuns and excludes. Howe had the other kind: the light that welcomes. That, even more than the greatness, explains the sadness and the shock and the sense of personal, familial loss in the hockey-positive parts of this continent—devastating enough that it seems reasonable to guess that had there been a Stanley Cup Final game scheduled in the hours after his passing, it would have been postponed, less out of respect than from grief.

It could just have been postponed by awe.

On the night of that game Corey Hirsch attended, Howe was two days shy of his 52nd birthday. The biblical-worthy longevity of his career gets much attention now, but between it, and playing alongside his sons, and the fan accessibility, some of the greatness gets understated.

Claim whatever you want about the improvement of hockey in particular or athletics and athletes in general, but Wayne Gretzky and Bobby Orr are right: Howe is the greatest ever to play the game, and showing the math is easy. In the first 21 years of his career, he scored 649 goals, was credited with 852 assists, spent 1,421 minutes in the box, won six MVP awards, six scoring titles, nine All-Star first team nods, and added 65 playoff goals.

And in those 1,398 games in which he produced just his pre-expansion, pre-WHA numbers, he was, every night from the first pre-season scrimmage to the last game of the Stanley Cup, playing against one of the six best teams in the NHL (at worst against one of the top 10 professional teams in the pre-1967 world). He was trying to score against one of the best dozen goalies, get past some of the best three dozen defensemen, beat up the best handful of fighters. Competitively, it was as if every night, every instant, of Gordie Howe’s first 21 years in the NHL began somewhere between the current second round of the playoffs and the Conference Finals.

And lastly there’s the unknowable and presumably most impressive stat of them all: How many thousand photos did he take with fans?