Gretzky offers context, insight into his legend with "99: Stories of the Game"

The publicity blurb for Wayne Gretzky’s new book, 99: Stories of the Game, posits that the single most dominant athlete in North American sports is “arguably” the best hockey player of all time. This is akin to suggesting that maybe the Beatles were the best rock band, Shakespeare your leading playwright of the Elizabethan age, or that maybe Alfred Hitchcock was the master of cinematic suspense. It’s a pleasing burst of humility in an age of the perpetual chest thump, but one that might cock the eyebrow of a cynic.

Gretzky has never exactly taken a hard line, either in his interviews, or something like his 1991 autobiography, in which the worst he has to say about anyone is that he thinks Mike Bossy is rather hubristic, though then again, a goal scorer kind of needs to be. We’re not talking Alexander Pope-like blasts of candor.

Gretzky’s always been a bit “aw shucks,” which is what, in part, makes this book the surprise it is. I read a lot of hockey books. I read all kinds of books, and I like when books can be ostensibly about one subject but appeal to people who believe they have no interest in that particular subject, even if they revile that particular subject. But what I really wasn’t expecting to learn was that Gretzky was also the king of finely crafted hockey writing.

We see him, for instance, pondering the curve—or the lack of one—of Howie Morenz’s stick at the Hall of Fame. Morenz was a Canadiens player in the 1920s and 1930s who had a grisly on-ice accident that ended his career, tumbled him down into a deep depression on account of losing the sport he loved, which led to a nervous breakdown, and then a fatal heart attack, at thirty-four.

Wayne Gretzky returns to Oilers in executive role

Teenage Gretzky, as we learn in the opening chapter of this book, would ditch his friends—who’d tease him—to go to the Hall of Fame in Toronto yet again, to study Morenz’s stick. Proust had his madeleine cookie, and Gretzky had Morenz’s stick.

He proceeds to discuss it—its thickness, pliability, the nail in the portion where blade and shaft meet—and then expands on how Morenz must have skated, what his sight lines would have been, how he would have had to use his angles and edges, what his pass and shot selection would have been like. It is pure geometric poetry, with a kind of romantic forensics that would, for Gretzky, like so many other such mental excursions for Gretzky, pay off in his own NHL career.

There was a program that went out in Britain in 1955, which only ran for a handful of episodes, called Orson Welles’s Sketch Book. Welles would plump himself down in front of the camera, nominally draw something, even though he wasn’t really drawing, as the lens framed him in its center, then proceed to talk. To tell stories. From narrative, Welles ventured into ideas, from ideas back to story, so that everything became this one big life blend, and the little pauses, the little beats, became lacunae that said so much, too, in the context of what surrounded them.

This Gretzky book is like that, the Wayner’s Sketch Book, you might say, just as his playing style was founded on those interstices, those little rips and gaps in space and time that no one else saw.

He could be a hockey historian professionally, which is a neat thing to learn. Like, who knew? But it’s the presentation of a way of seeing that alters everything.

Ever been to a museum with someone who really knows art? Someone who is going to make it so that you can never see a painting again in the same way? Never see the natural compositions that present themselves at a dinner party in the same way? That’s what Gretzky does here, and you will never watch a hockey game in the same manner again.

He discusses the geometrical realities and challenges of the old Boston Garden, the history of the Blackhawks, all three editions of the Canada Cups he partook in, the Socratic lessons to be learned of the New York Islanders dynasty, and Willie O’Ree, the first African American to play in the league.

Wayne Gretzky: Off the Ice

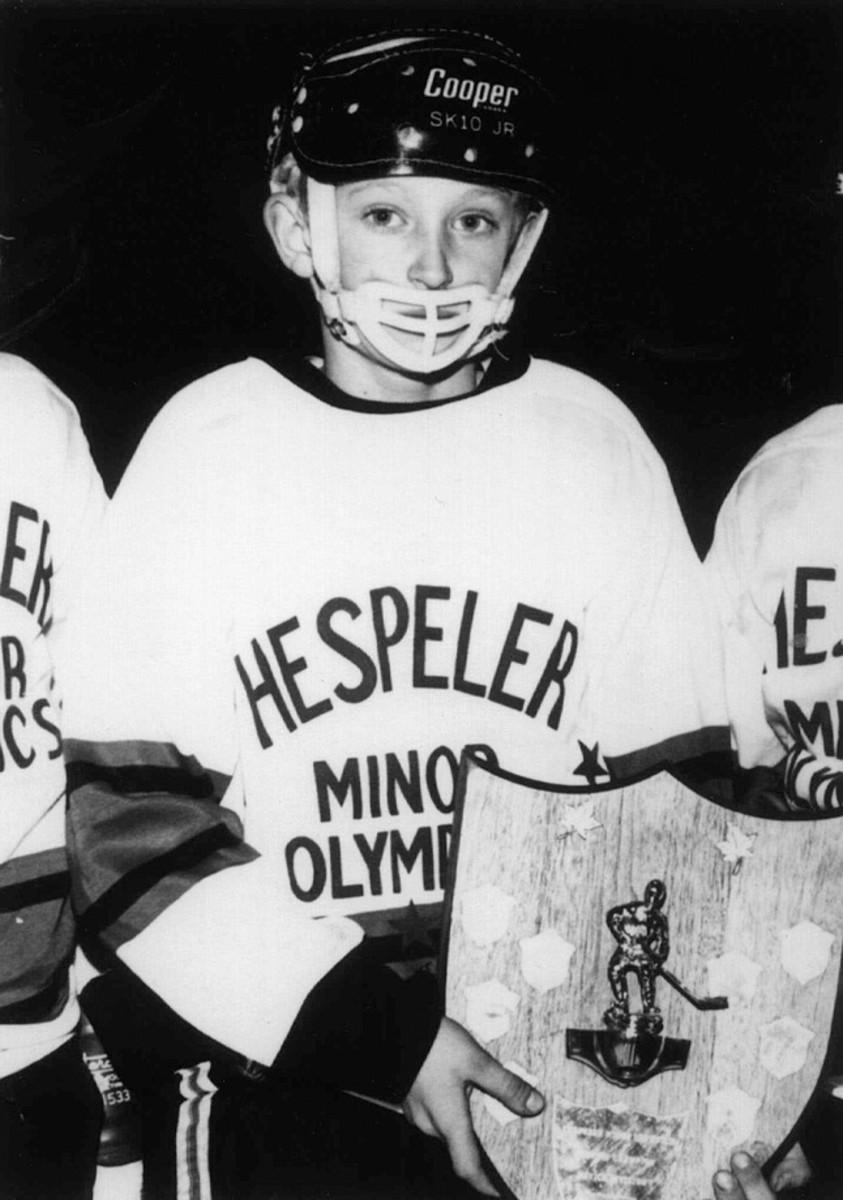

At age nine, Wayne Gretzky was a youth hockey phenomenon in Canada. As he progressed quickly from level to level and dominated against much older players, some newspapers called him "the next Bobby Orr" for his speed and skill.

The future Great One laced up his first pair of skates and spent countless hours on a rink built by his father in the backyard of their home in Brantford, Ontario. By the age of five, Wayne was competing against kids who were 10 or 11 years old.

At age 11, Gretzky was running wild in his Pee Wee league in Brantford. Nicknamed "The White Tornado" for his white gloves and speed, he scored 378 goals ... in one season. In one Pee Wee league game, Gretzky potted three goals in 45 seconds. "He would never come off the ice," recalls Darren Eliot, who played against Gretzky in the same league. "He moved to defense instead of actually taking a break on the bench."

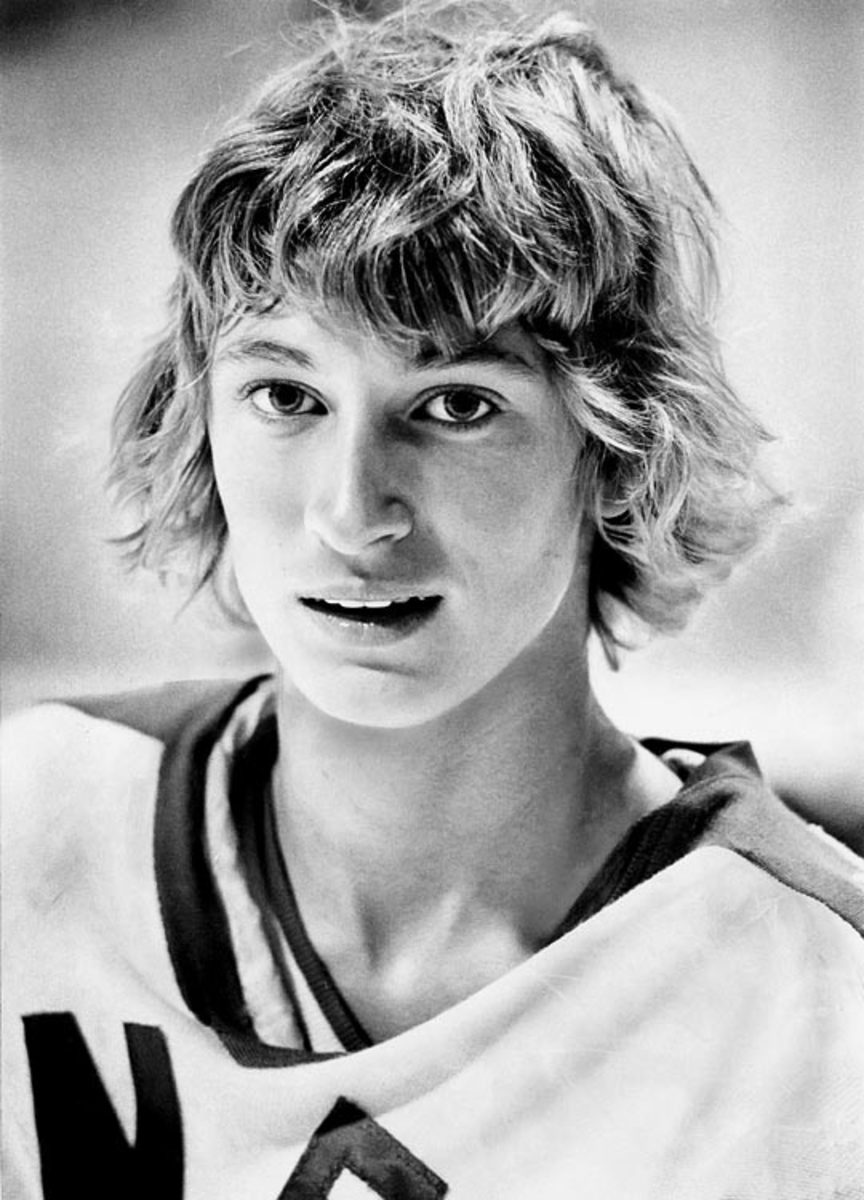

By age 14, the curly-topped phenom was a target of resentful parents in Brantford, some of whom cheered when he was injured during a game, so he moved to Toronto to play minor hockey for the Nationals.

Gretzky, 17, scored 70 goals and 182 points in 63 games for the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds of the Junior A Ontario Hockey Association and was the youngest player on Team Canada at the 1978 World Junior Championship in Quebec City. (He lead all scorers with eight goals and nine assists in six games.) Despite his prowess and uncanny on-ice sense and vision, some scouts feared he would be too small to play in the NHL.

Gretzky lived with a local family while he played in Sault St. Marie, Ontario. Here, the 17-year-old enjoys a neighborhood game of street hockey.

Gretzky throws a check, something rarely seen in his professional days, during a game of street hockey.

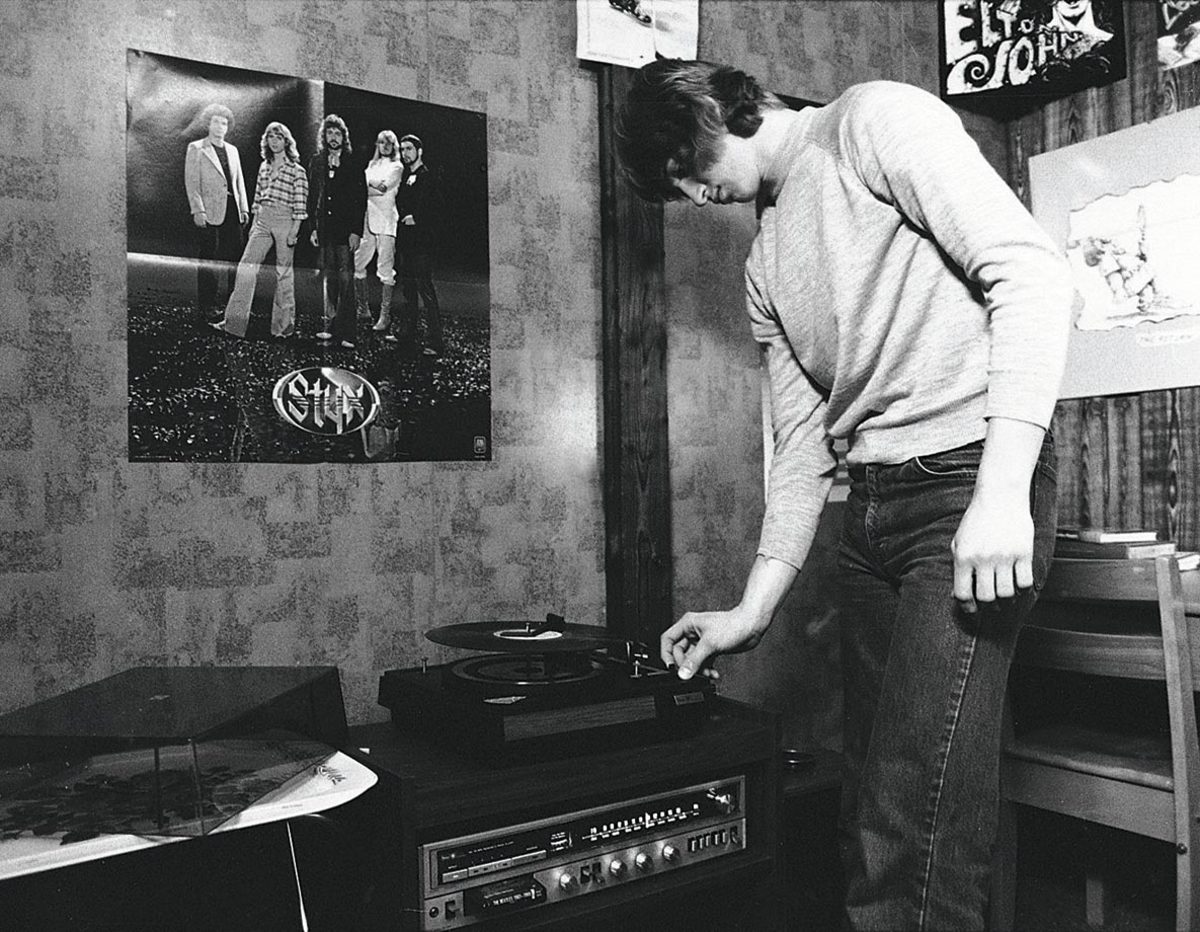

Obviously partial to the progressive sounds of Styx, the 17-year-old Gretzky spun some hot wax on his stereo in the Bodner family's house in Sault Ste. Marie.

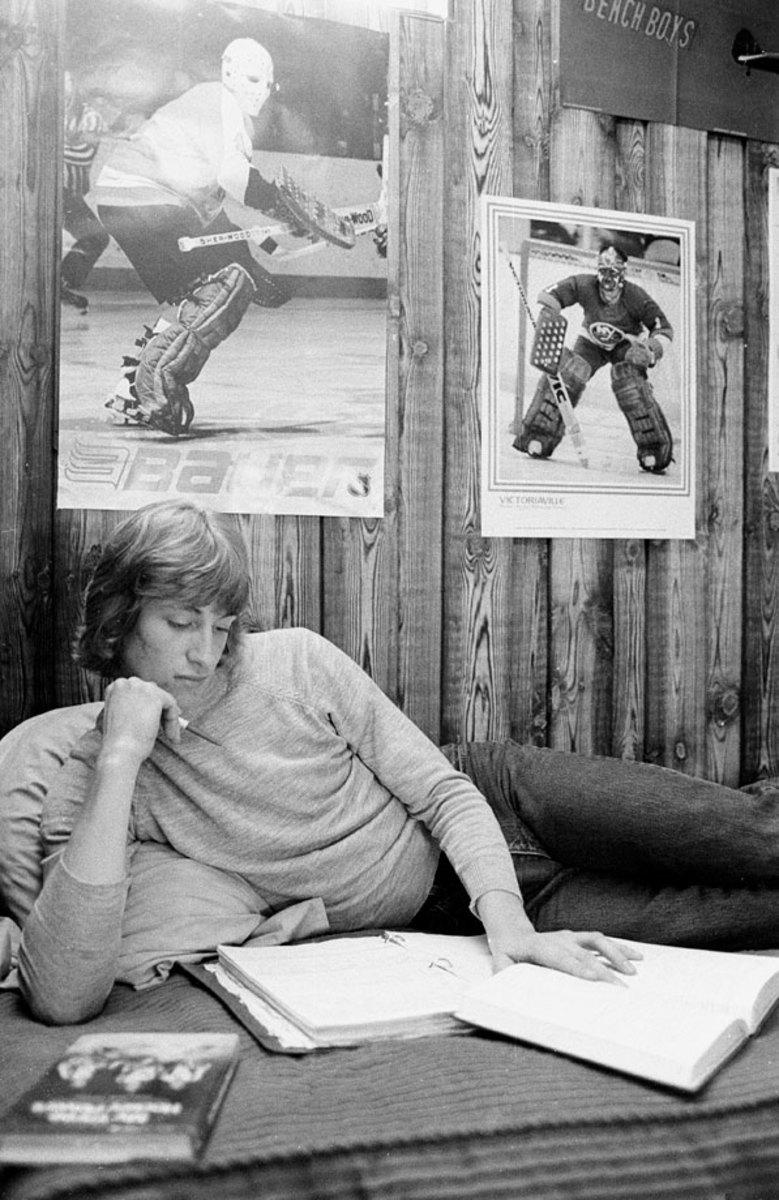

The teen phenom, seen here in his room at the Bodner family's house in Sault Ste. Marie, tried to keep up with his schoolwork as a pro career loomed.

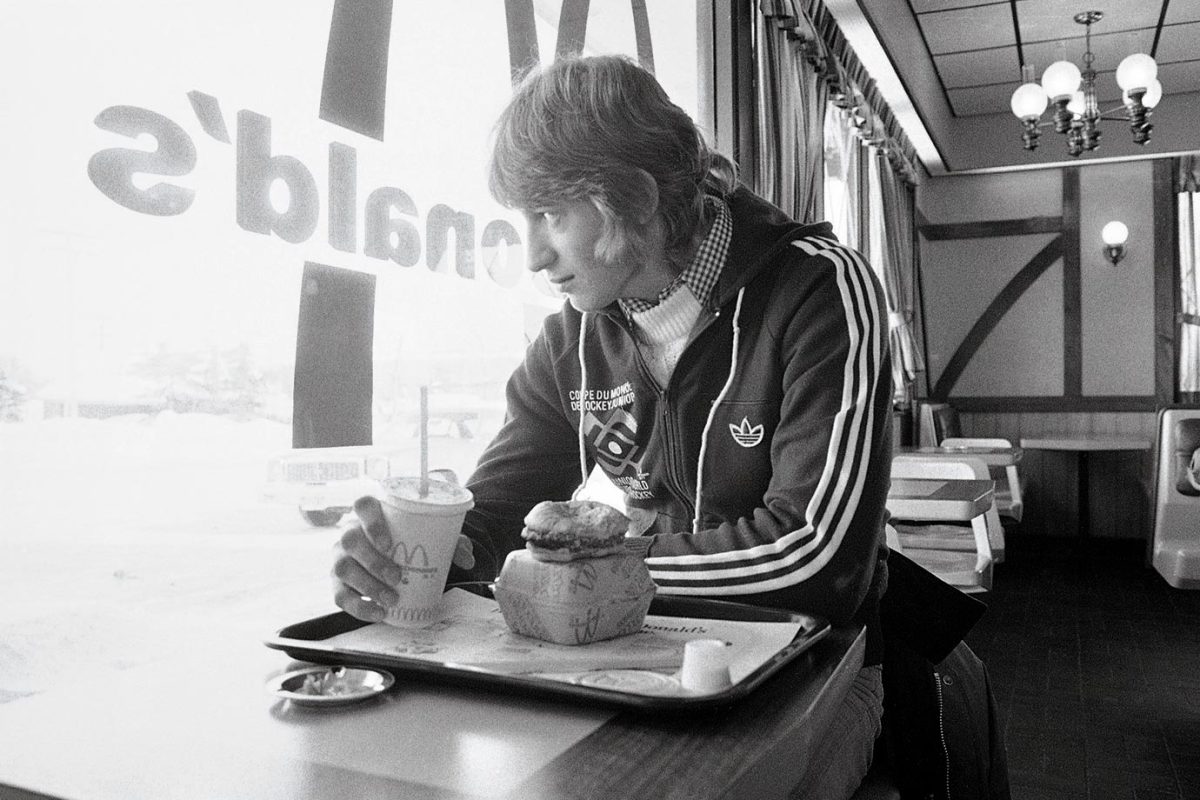

The future Great One grabs some grub at a McDonald's in Sault Ste. Marie.

Gretzky would go on to sponsor numerous businesses in his pro days, including McDonald's.

Gretzky had played only eight games for Indianapolis when the team folded. He was sold to the WHA's Edmonton Oilers, with whom he signed a 21-year contract worth $1 million per season on his 18th birthday. The Oilers were absorbed by the NHL later that year and Gretzky's accomplishments and legend would reach unprecedented heights.

Gretzky had good reason to smile before the playoffs in '81. He would go on to score 21 points (7 goals and 14 assists) in just nine games that postseason, before the Oilers were eliminated by the defending Stanley Cup champion New York Islanders in the second round.

Gretzky and the Oilers quickly became a force. Here, he playfully interviews two of his most notable teammates -- future Hall of Famers Paul Coffey and Mark Messier.

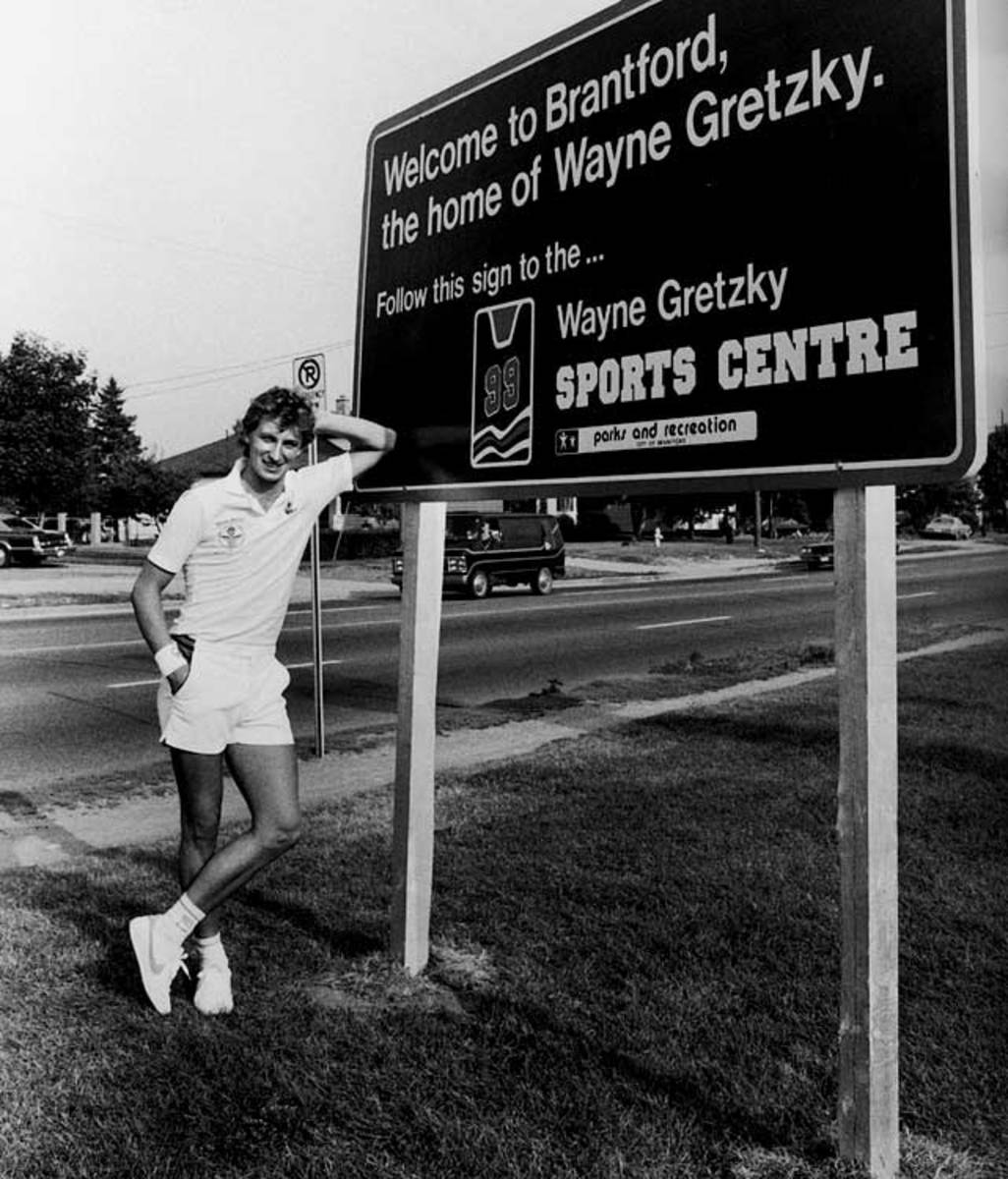

Only four years into his pro career, Gretzky had put his hometown on the map.

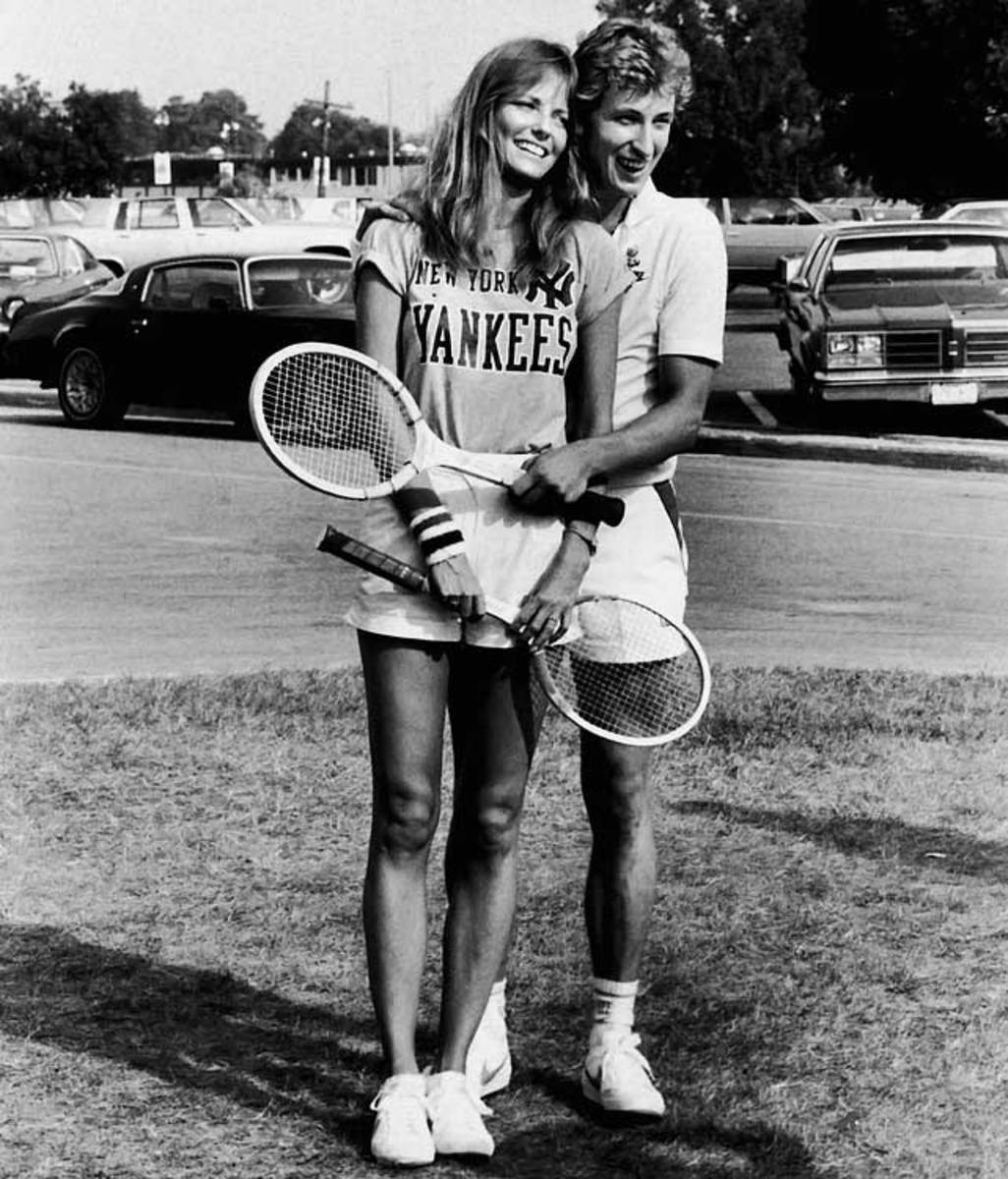

One of the perks of fame is you get to hobnob with models. Here, Gretzky schmoozes with Cheryl Tiegs during his charity tennis tournament.

The Oilers reached their first Stanley Cup Final in 1983, only to be swept by the four-time defending champion New York Islanders. Gretzky congratulated Islanders GM Bill Torrey, who told him, "Don't worry, kid. You'll be back next year." Torrey was right. In 1984, Gretzky and the Oilers dethroned the Isles in five games.

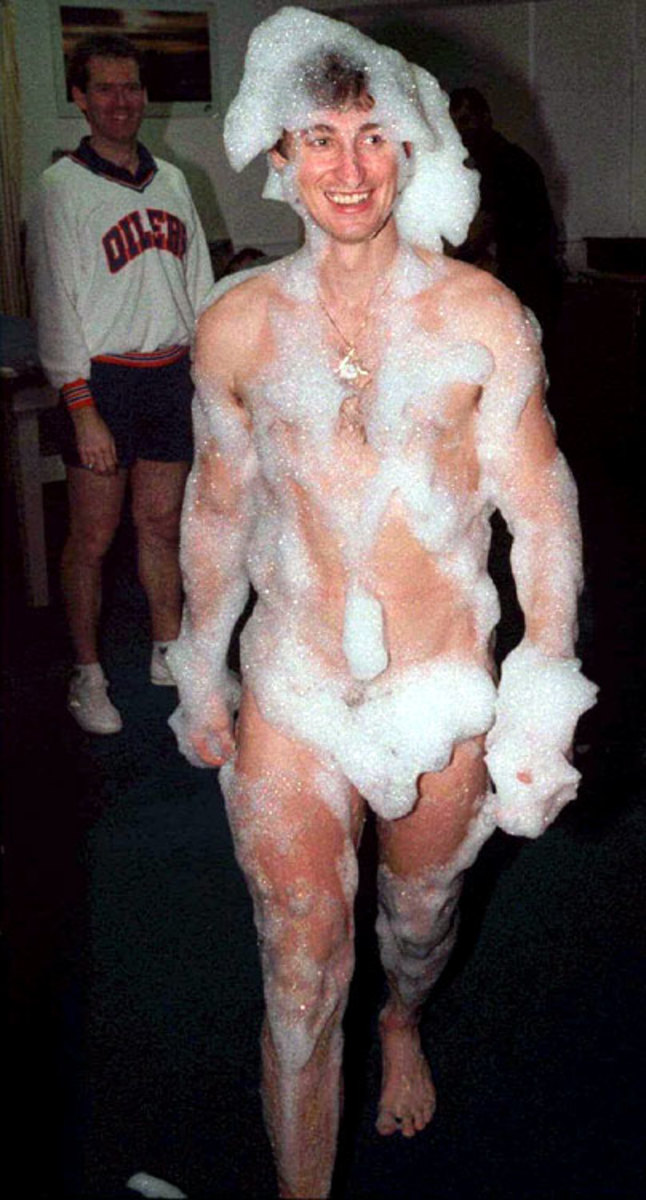

Mr Bubble: The Great One parades through the Oilers' dressing room. By that time, he was routinely shattering scoring marks and his Oilers were becoming a dynasty that would win four Stanley Cups in five years.

Gretzky married actress Janet Jones on July 16, 1988 in a ceremony that was tantamount to a Royal Wedding.

Gretzky's trade from the Oilers to the Los Angeles Kings in August 1988 was a landmark event for hockey in the United States. The Great One was welcomed to L.A. by Lakers superstar Magic Johnson.

Wayne Gretzky holds his four-year-old daughter, Paulina, after a press conference in Inglewood, Calif., on Jan. 4, 1993. It was announced that the Los Angeles Kings team doctors cleared Gretzky, who hadn't played all season due to a herniated thoracic disk in his back, to return to the game.

Gretzky lines up a shot during a golfing event in 1994, using a club he's more familiar with.

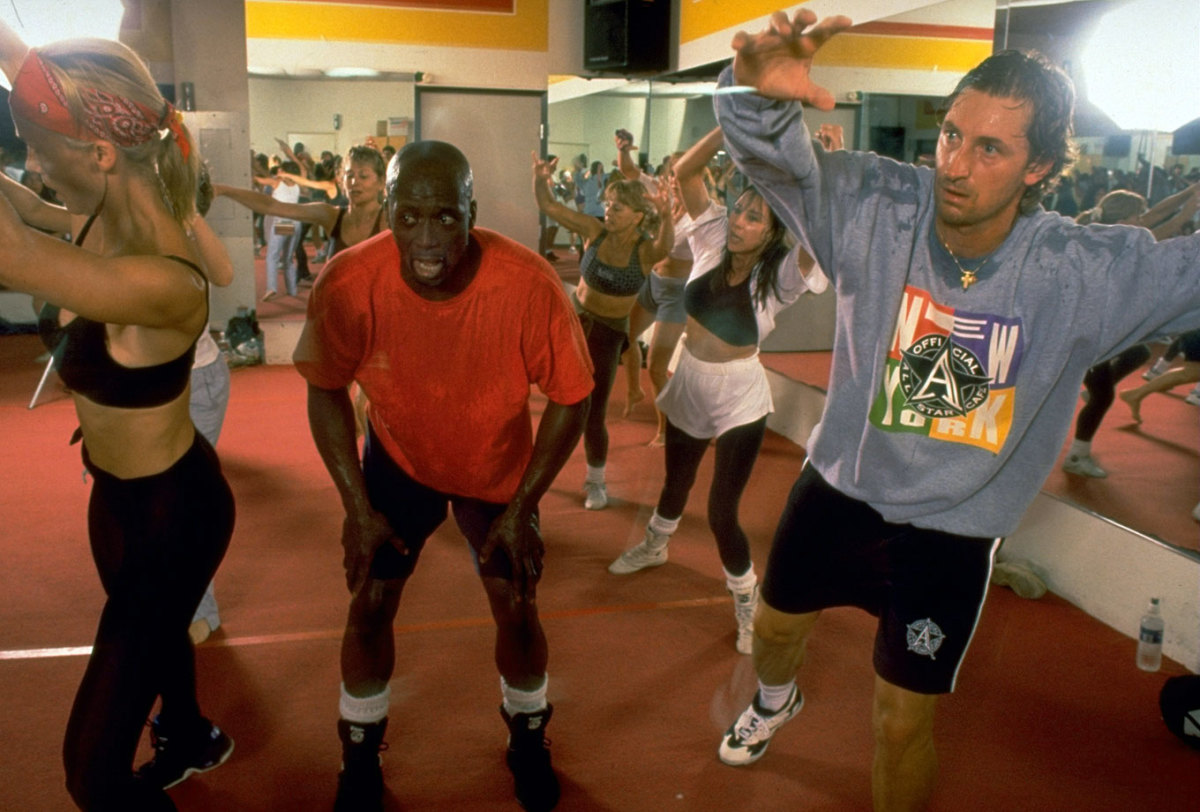

Wayne Gretzky breaks quite the sweat in an aerobics class taught by Billy Blanks in 1995.

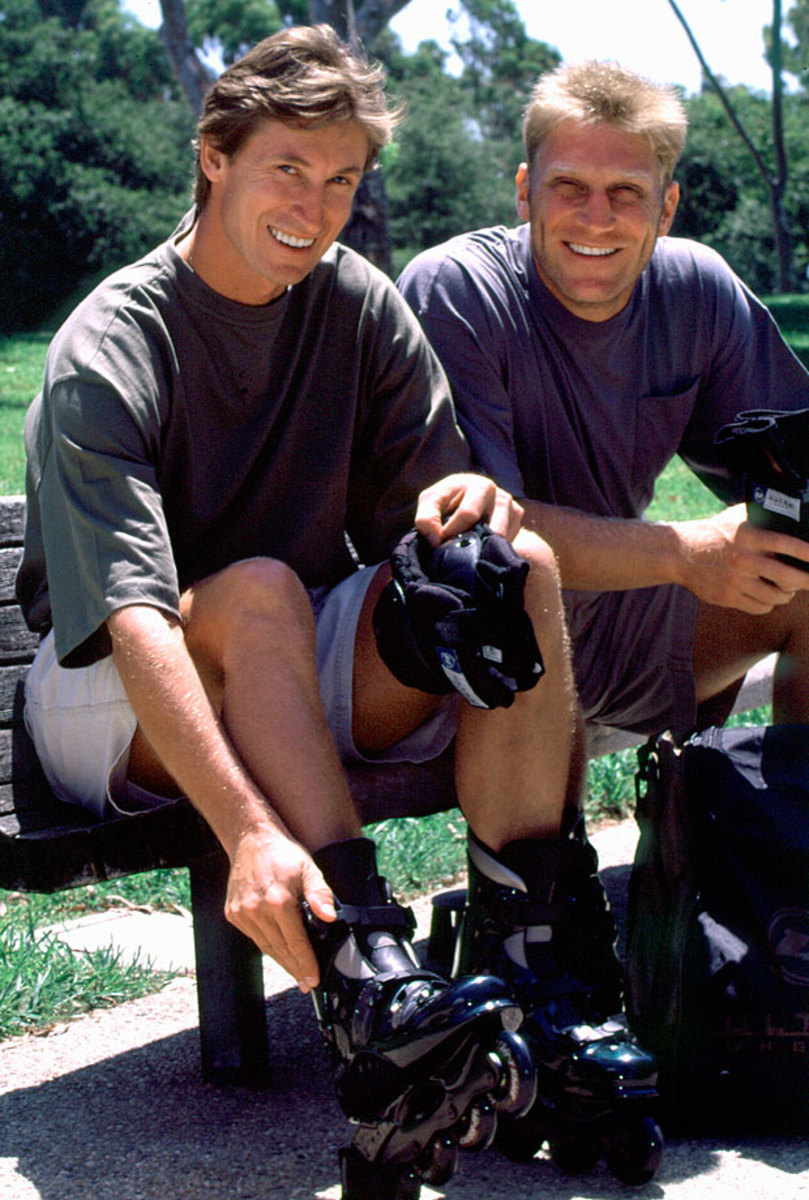

Gretzky and Brett Hull gear up with inline hockey skates in Los Angeles following the 1995-96 NHL season.

By 1996, Gretzky had moved on to the New York Rangers after a brief stay with St. Louis, reuniting him with former Oiler teammate Mark Messier.

Wayne Gretzky sits with his family, wife Janet and their kids Trevor, Paulina and Ty in 1997.

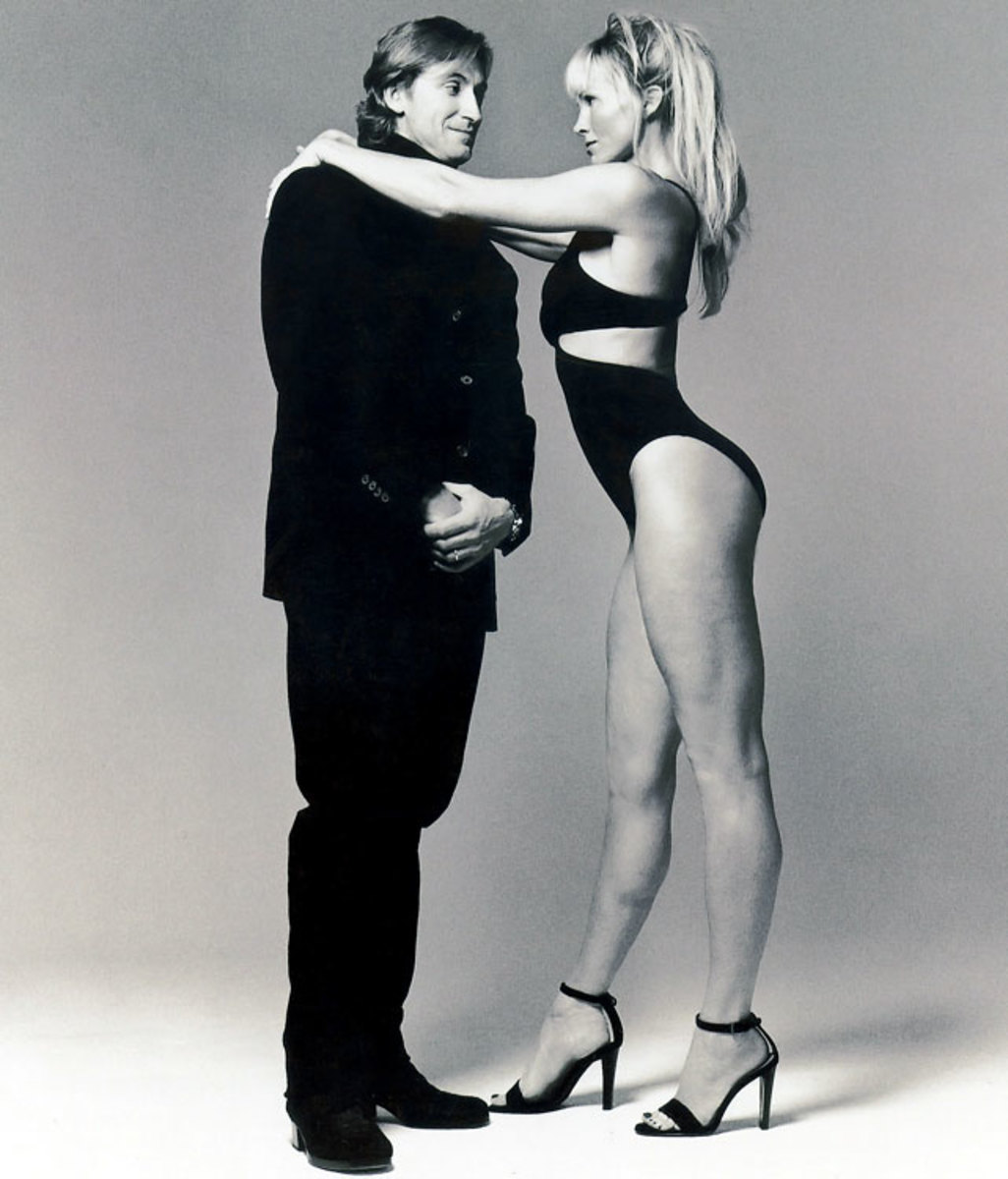

The Great One and his wife Janet graced the 1998 Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue.

Gretzky readies a backhand swing at Indian Wells during the Pro Am Tournament to Benefit the Prostate Cancer Foundation in 2004.

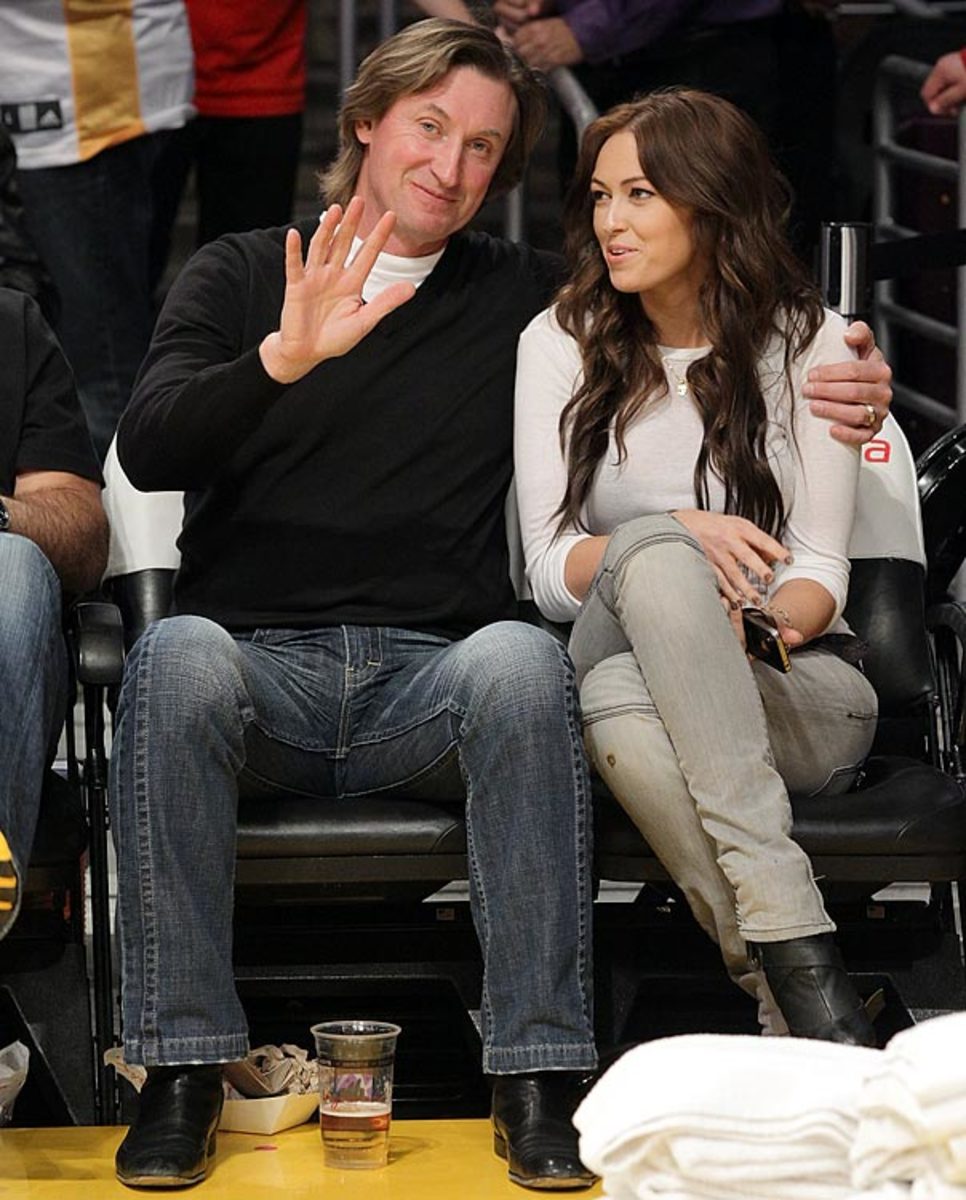

Gretzky and his daughter Paulina attend a Lakers game against the Jazz at Staples Center in 2011.

Wayne and Janet take in a Kings game against the Blues at Staples Center in 2013.

Pro golfer Dustin Johnson looks up to his future father-in-law, Wayne Gretzky, during a photo shoot in Los Angeles on Jan. 9, 2015. In “The Great One,” Johnson has a father figure who can teach him a thing or two about handling fame.

Bossy gets his props, and Gretzky even tells us how, in part, he scored so many goals, in an anecdote that involves Bossy shooting on longtime Oilers’ goalie Grant Fuhr, one-on-one.

There is a hilarious chapter on the origins of the Lady Byng trophy, starring Lady Byng herself. I mean, admit it: you have always wondered what the hell that is about, an NHL award named the Lady Byng? Come on. That seems incongruous.

Gretzky details what was known in the early 1920s as “hell on ice,” of which our Lady Byng was a huge fan—violence aside—and in regular attendance at the games. We see the villainously named Sprague Cleghorn “playing with a nail on his stick” and this horrified Lady Byng, especially when Cleghorn broke the arm of the Senators’ Frank Neighbor, who happened to be her favorite player.

“As it happened,” Gretzky writes, “Neighbor was also her neighbor.”

Number ninety-nine with the joke! And a good one at that. Byng invites Neighbor over to her house, asks if he thinks it’d be good to have an award for gentlemanly play, he says sure, and that’s how the trophy came to be. A guy just had to have his arm broken and be attacked by a dude who wielded a stick with a nail in it.

Wayne Gretzky lending his voice to 'The Simpsons'

Then there’s Walter Gretzky, Wayne’s father, who is all over these pages. If you play hockey, there is a very good chance you have a special relationship with your parent, because you will have spent hundreds, if not thousands of hours, together in cars, at super early hours of the morning, just the two of you, driving to rinks, then driving back again.

Walter was also something of an artistic conscience for Wayne, Virgil to his Dante.

When the Flyers began to assert themselves in 1973-74, with their proto-Slap Shot tendencies, Walter says to his son, “This is not good for you.” Gretzky is baffled, and prompts his dad to explain that the rough and tumble style of play would be less than ideal for Wayne’s talents.

You imagine him, years before he’d be in the league, knowing he would be, trying to think his way through the problem. He’d have solved it, too, you’re confident in thinking, though the 1970s dynastic Canadiens bailed him out, in some ways, with their graceful play.

That team featured Ken Dryden, and for most of my life I have held his The Game as the best hockey book ever written. It’s one of the best nonfiction books I’ve ever read, and I always have some machination going where I’m trying to pass it off on some friend who could care less about hockey, saying—and not untruthfully—that you do not have to give a fig about vulcanized rubber to love this book.

I can say that more about this one. The meeting at the office, I suspect, looks different after reading how Gretzky thinks, ditto the painting on the museum wall; the Bach fugue sounds different, and you’ll see overlap in terms of geometry, misdirection, anticipation, the way the familiar is recast and always made new again.

The man has every record there is, might as well notch his name down for best hockey book. And you are going to want to make like you’re trying a wraparound attempt and ram this into some stockings this year. Credit Gretzky with another of his endless assists, I suppose.