How the Washington Capitals turned in—and recovered from—the worst NHL season ever

In Largo did Abe Pollin

A stately pleasure-dome decree;

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

—Tom Dowling, The Washington Star. July 2, 1972.

The late Abe Pollin was a builder, a graduate of George Washington University who stuck around the District of Columbia to make his mark. Construction was the family business, so he raised apartment complexes around the beltway, from low-income units in southeast D.C. to a chic, 17-story building in suburban Maryland, named for his wife, Irene, who still resides in the area today.

Pollin’s investment group bought the NBA’s Baltimore Bullets in 1964, and four years later he assumed sole ownership. It wasn’t long until he started itching to bring pro hockey to the area, too. And so, on June 8, 1972, nine days before burglars broke into the Watergate Hotel, as war raged overseas in Vietnam, locals forked over 10 cents for a copy of the Evening Star and read the triumphant news splashed across the front page: D.C. GETS NHL FRANCHISE.

It was the result of a bidding race that saw Pollin marshal support from 17 U.S. Senators and 42 representatives in the House, who wrote to the league’s board of governors over the weeks leading to its expansion vote. The 11th-hour push paid off: Washington and Kansas City outlasted eight other groups from six different cities and would begin play in the 1974-75 season. The entrance fee cost Pollin $6 million. (Pittance compared to the $500 million due from Las Vegas Golden Knights owner Bill Foley before his team debuts next fall.) Another $16 million from his pockets went into erecting the Capital Centre, a 17,962-seat arena in Landover, Md., which touted its revolutionary Telscreen, replete with “dramatic full-color closeups and instant replays.” This all made Pollin a lauded man in the D.C. sports scene. OUR NEW HERO, another Star headline called him.

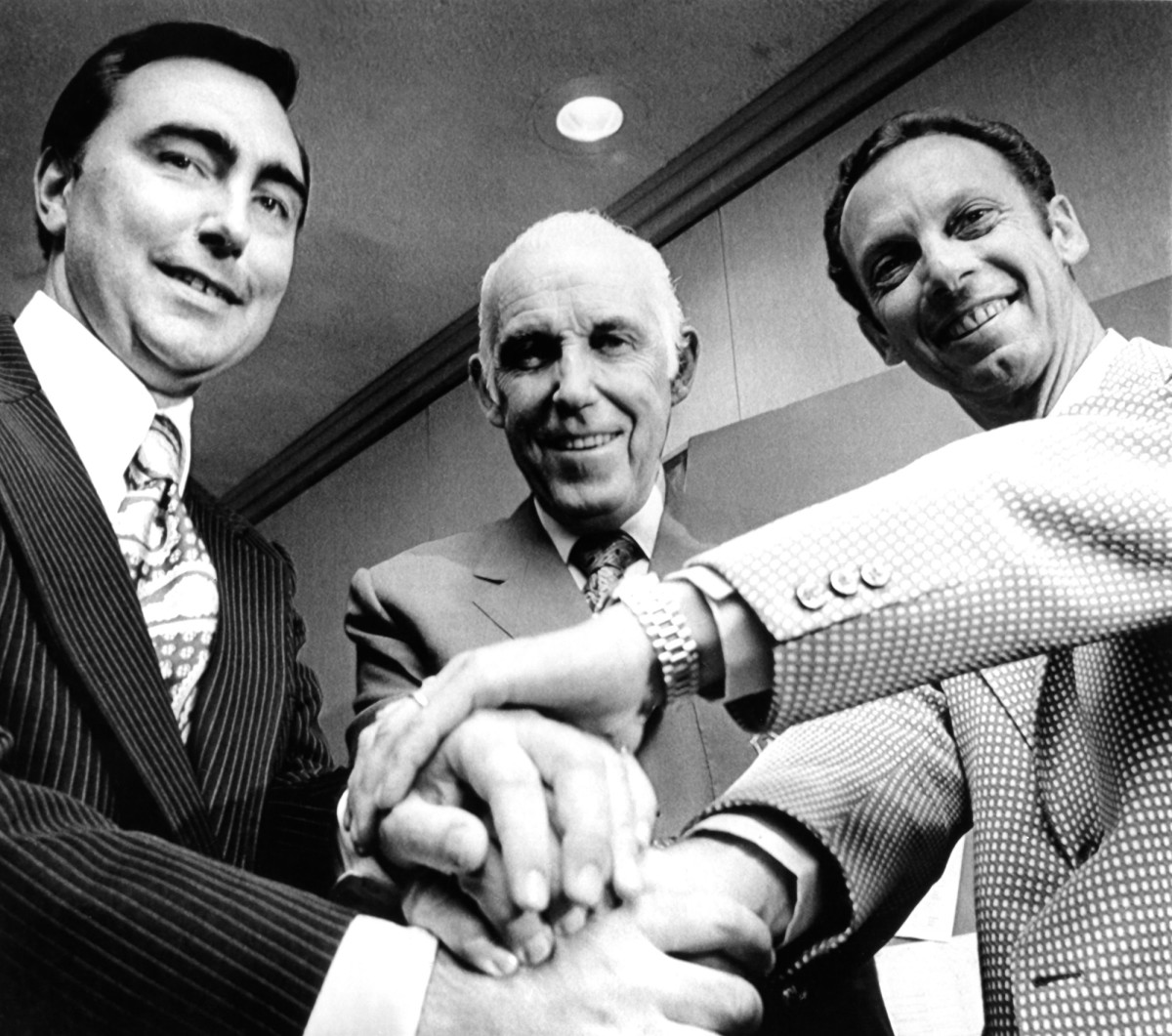

The franchise took shape over the next two years. Milt Schmidt, the Hall of Fame center on the Bruins’ famed “Kraut Line,” and more recently an executive and coach for Boston, was brought aboard as general manager. “Why inherit someone else’s problems when I can start something for myself?” Schmidt said at his introductory press conference, promising a “highly competitive” team within three years.

For other key positions, Schmidt sought familiarity. His right-hand man in Boston, Lefty McFadden, was tabbed as assistant GM. Red Sullivan, his chief talent scout, would fill the same job in Washington. Jim Anderson, the Bruins’ former minor-league bench boss, became head coach. Some 12,000 fans entered a contest to name the team; common submissions included the Domes, Cyclones, Streaks, Pandas, and most popularly, the Comets. Abe, however, chose one he felt “fit in just fantastic.”

The NHL's 10 best single-season teams

What followed was instead, by many measures, the worst NHL season ever. To date, no team has played at least 70 games while posting fewer points (21), wins (8) or road wins (1) than the 1974-75 Capitals. Nor has any mustered a lower points percentage (.131), allowed more total goals (446), or dropped more contests consecutively (17).

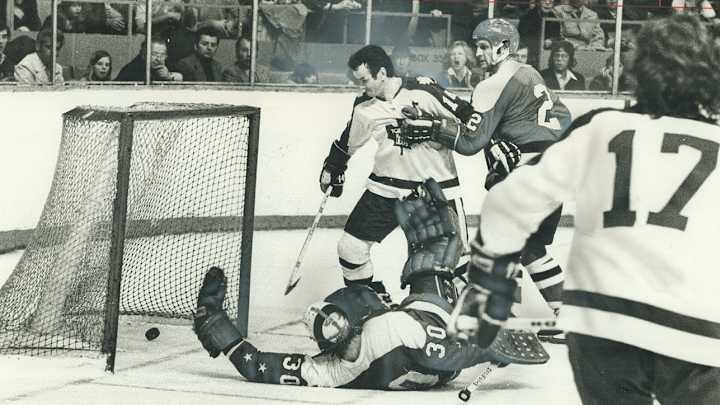

The wreckage featured four losses by double digits, and 10 in which Washington scored no goals. It saw backup goalie Michel Belhumeur make 35 appearances and record zero wins. It got Anderson fired by mid-February, and then sent Sullivan, his hasty replacement, into the hospital with stomach issues after five weeks on the job. It took until March 28 to win on the road. It reshaped careers and recolored legacies.

Yes, 8–67–5 record is a miserable sight, even four-plus decades later. But the season remains a memorable experience for those most intimately involved, the players who understood, like Pollin, that building something means finding folks to dirty their hands and lay the first bricks.

“You knew sooner or later that market was going to take off,” says Jack Lynch, a defenseman on the original team. “We just weren’t the ones who were going to enjoy that prosperity.”

This is their story, in their words.

“WE WERE HIGH AS KITES”

The Washington Capitals hockey team was born yesterday in the crowded Grand Salon of the Queen Elizabeth Hotel. The baby stood 136 feet tall, weighed 4,920 pounds and cost its papa, Abe Pollin, $6 million … The skeptics howled. “Won’t win a half dozen games,” one said. “A crime,” said another. “Nixon will certainly desert Washington now. This and Watergate will be too much.”

—Washington Post, June 12, 1974.

Bill Mikkelson, D: A lot of us were taken in the expansion draft. That’s how we ended up there.

Jack Lynch, D: If you look back at the protected list and who they could pick, it was pretty pathetic. You were getting the 17th, 18th-best player on the roster to build a franchise around.

Mikkelson: I think we were all fortunate to be there, the players on that team, at that time in our careers. I don’t want to make it sound derogatory. A lot of us were fourth-liners or whatever on NHL teams, struggling to get ice time.

Murray Anderson, D: We had a really, really, really good American Hockey League team. I was just a small cog in a very small wheel, because it was just too many small cogs to make a big wheel. Does that analogy make sense?

Two weeks before the mid-June expansion draft, Washington had won the first-overall pick in the amateur draft (over Kansas City in a coin toss). The Capitals selected Regina Pats defenseman Greg Joly. Handsome, bilingual, smart and the eventual owner of a sleek white Thunderbird and a five-year, $400,000 contract, Joly had led the Pats to the Memorial Cup and was named MVP.

GM Milt Schmidt (to the Post): Joly can do a lot of the same incredible things that [Bobby] Orr does. He skates extremely well, is intelligent and can either pass or carry the puck out of danger. He’s shown signs that he can score like Orr, too.

Ron Low, G: He was going to be the messiah. And he was a hell of a hockey player. There was just way too much pressure on him.

Mike Bloom, F: He got a lot of money for the time. Even guys on the other teams would go after him, physically go after him, because they were jealous.

Anderson: They were throwing this kid to the bloody lions.

Nelson Pyatt, F: Gregger used to always say, “Nelly, circle the wagons, here they come again.”

Bloom: But just we were all average. We didn’t really have a supporting cast. We just didn’t have the talent.

The roster that assembled at training camp in London, Ont., certainly did not project success. “It’s disgraceful that owner Abe Pollin… can’t appeal to the Better Business Bureau,” wrote Russ White of the Post. Of the 54 attending players, none had scored 10 goals in the NHL the previous season. Among the more decorated reports was Tommy Williams, an Olympic gold medalist with the United States in 1960 at Squaw Valley.

Ron Lalonde, F: We used to joke about his flight patterns. Nobody knew what he was going to do. We called him ‘The Bomber.’ He was on these flight patterns of skating around, and hopefully someone found him with the puck.

NHL 100: Celebrating 100 years of hockey's greatest players, moments and more

Jack Egers, F: Loved to party, loved to play hockey.

Yvon Labre, D: He had a big belly on him, so you can’t tell me he was in shape.

Pyatt: Those older guys, they were just playing out their cards.

Low: We were definitely outmatched muscle-wise most nights in any barn. Yvon Labre took way too many beatings for his teammates with guys he had no business fighting.

The captaincy was awarded to Doug Mohns, whose contract had been purchased from Atlanta, was a veteran of 1,315 NHL games, almost as many as the rest of the roster combined. He entered camp at 40 years old; no one else was older than 26.

Bill Lesuk, F: I had a lot of respect for Doug.

Anderson: He was Grandfather Time.

Egers: The senior man, the calming influence when we’d get frustrated.

Pyatt: When I got into the league, I wasn’t much of a guy with fashion. I had one suit, an old corduroy suit, and the guys would say it was my marrying-and-burying suit. Dougie pulled me aside and said, “You’re in the big leagues, you’ve got to dress accordingly.” He knew a tailor in Montreal, and sure enough we went out, he made me three designed suits. He was a mentor-type guy you looked up to.

Another experienced forward was Steve Atkinson, a one-time 20-goal scorer with Buffalo. The dour preseason predictions left him steamed: “We don’t get a damn bit of respect,” he said. “People claim that we won’t win 10 games. It’s baloney.”

Five days later, Atkinson was eating steak at lunch before the exhibition opener, choked on a piece, and wound up in the hospital. (He missed the game but was fine.) That night against Buffalo, the lineup card listed the team as the Washington Generals, the Globetrotters’ punching bags.

In other words, the fertile hockey ground was ripe for comedy.

Lalonde: It was almost like a traveling circus. You didn’t know what was going to be happening at the other end.

Low: There were a lot of really good people on the team. Otherwise we would’ve all gone insane, I think. I’m not too sure we didn’t anyway.

The Future of Hockey: How the game looks now and how it is evolving

Egers: At training camp Stan Gilbertson and I got suspended for keeping beer in the tub of our hotel room. We had two workouts a day, so guys would come in after the second practice. Uncle Milty, he didn’t like that too much.

Lalonde: The practice facility in Tysons Corner (Va.), they had these gas-powered heaters, but the fumes from them almost made us pass out before we got out on the ice.

Lynch: The Cap Center was a beautiful rink, state-of-the-art, arguably one of the finer buildings in the league at the time. We shared training facilities with the Bullets, so when they put the benches in the locker room, they put them at the same height as what the basketball players wanted. We had 5’ 8”, 5’ 9” guys with their legs dangling, trying to put their skates on.

Lalonde: Even the color of the sweaters, they were still experimenting with. We had three sets of pants: Red, blue, and they started off with white, which I don't think there was any other team in the history of the NHL that had white pants.

Lynch: When I was in Detroit, before I got traded to Washington, the joke was that the Caps never had to worry about getting those pants dirty because they never went in the corners.

Lalonde: The problem with that was, in one of the exhibition games, Mike Marson, a black player, didn’t wear long underwear. When these white pants got wet, it was like he had nothing on. That put an end to the white pants.

Bill Mikkelson: We had to laugh at ourselves. I think we all knew our stature as far as caliber of players in the league go.

In the beginning, though, there was hope. A hat trick from Marson, a 19-year-old rookie who went in the second round of the amateur draft to become the NHL’s second black player ever, propelled the Caps to their first preseason victory, 6-4, over Detroit on Oct. 3. They then swept expansion brethren Kansas City, rolling into the regular season on a three-game winning streak.

Bloom: I had played two years in the Bruins system, so I remember going to training camp and knowing most of the guys. I’d played against them or with them. We didn’t think we’d be as bad as we turned out to be. I thought we did okay in the exhibition games.

Labre: We tied Montreal, 4–4, at the Cap Centre.

Mikkelson: There were legends and Hall of Famers in that Montreal lineup.

Labre: Boy, we were high as kites before the season started.

Egers: We all went into it bright-eyed and bushy-tailed.

Labre: Then we just faltered. Winning snowballs? Well, it seemed that losing can also snowball, and it did.

“THERE WAS NO MERCY”

The Capitals dropped their regular-season debut, 6–3, against a Rangers team that outshot them 19-1 in the third period. One week later they earned their first standings point, a 1–1 tie with Los Angeles. Then they hosted Chicago. It was Oct. 17. The Blackhawks had arrived in town after 4 a.m., bleary-eyed on a back-to-back, and their fatigue showed on the ice. Twice the Caps scored when pucks deflected off Chicago players, but they were in no position to be choosy. They celebrated the franchise’s first-ever win, 4–3, with Egers notching the decisive goal.

Egers: I got a pass, went up the wing, took the shot and scored. That’s my claim to fame. Good trivia question for you to remember. I’m sure we got some headlines in the paper. Maybe someone even said things were turning around. They were wrong.

Bloom: I remember thinking, “We’re going to be okay. We’re not going to be that good, but we’ll be okay.” Then we lost about 20 in a row.

(For accuracy’s sake it was 10, including three shutouts and an 11–1 pasting to the Canadiens.)

Bloom: Denis Dupéré is from somewhere around Montreal. We’re on the plane coming back, and Dupéré says, “I come into the dressing room, my mother’s crying, my sister’s crying, everybody’s crying,” Because we got clobbered so much.

Low: It was hard getting up for games, going into buildings like Buffalo, where the French Connection line was likely going to run up 10. You go into Boston, and you’re probably going to get the crap beaten out of you because they had Phil Esposito and Ken Hodge and Bobby Orr.

Egers: Just a very long season when you’re getting pummeled.

Lynch: You knew you were going to lose. It was just how much you were going to lose by.

All In: Behind the scenes with the Golden Knights, Vegas's first major league franchise

On the rare occasion, though, sympathy prevailed. Egers remembers one big loss against Boston, when he and linemate Dupéré sprang free on an odd-man rush, bearing down on goalie Gerry Cheevers with only a backchecking Orr in their way.

Egers: Orr keeps backing up going, “Shoot, Duper, shoot.” He wants Dupy to get a goal, right? Orr’s right on Cheevers’ pads almost, and Dupy snaps it top corner. As I’m skating by the net, Cheevers says to Orr, “You can be such a prick.” I got an assist, Dupy got a goal, we were happy. That’s how bad it was. We were happy we got two goals in Boston.

Low: One night we were in Buffalo, and it was a beautiful, warm spring day, like 54 outside. They’ve got the shot clock up beside the temperature gauge. Yvon Labre came by and said, “Jesus Christ, Ronnie, if we give them one more it’ll be higher than the temperature outside.”

TV broadcaster Hal Kelly (to the Evening Star): It’s like being a singer and instead of having a philharmonic orchestra behind you, there’s a piano player. A bad piano player.

By New Years’ Eve the Capitals had won three times—once each in October, November and December. They ended the season’s first half with a 20th straight road loss, five shy of the league record, and promptly set that futility mark Feb. 1 in Vancouver.

Later that month, while Pollin was playing tennis on vacation in the Virgin Islands, Schmidt traded Dupéré, then the team’s leading scorer and its lone all-star, to St. Louis for forwards Garnet (Ace) Bailey and Stan Gilbertson. Schmidt then removed Jim Anderson as coach, replacing him with Red Sullivan, the head scout.

Bloom: It wasn’t [Anderson’s] fault. That was a horrible job. Almost like a mercy firing, you know?

Low: I don't know how that man didn’t have a nervous breakdown.

Murray Anderson: It was a turnstile. We just didn’t know who was going to be in the lineup that night.

Lynch: They were constantly bringing guys up from Richmond, sending guys down, just trying everything. How do you build a team when you have that kind of turnover? There was no consistency. They were really grasping.

Dave Kryskow, F: I was frustrated after one game. I said something to a reporter, like, “When is this going to end? When are they going to send these kids down to the minors and replace them with some people who have experience?” I was traded to Detroit about two or three days later.

Mikkelson: What an opportunity for opponents to rack up points, pad their scoring totals. They’d never let up. They were winning 6-1? They’d want to lead 12–1. There was no mercy.

Few better symbolized the struggles—and has received more attention for them—than Mikkelson, a stay-at-home defenseman who’d already gone through the expansion experience once before, with the Islanders in 1972.

Mikkelson was coming off a strong season for the AHL’s Baltimore Clippers in ’73–74, finishing plus-44 in 75 games, and put in the work to make the permanent leap into the NHL after the Caps took him in the expansion draft; the Post reported that he quit smoking cigarettes, swore off alcohol and coffee and lost 10 pounds.

Entering camp, tragedy struck.

Mikkelson: My brother had been killed in a car accident in October, just before the season started. I remember getting the news. It was at warmup time before the game. I remember sitting in a room to the side of the dressing room by myself for a long time, with the game going on.

Bloom: Billy was a quiet guy, good guy, not at all emotional. But he came back in and was crying, throwing stuff around.

Mikkelson: That casts a pall on the whole year, the whole winter. I guess you just deal with it. Whenever I think back on that year, there’s two things that come to mind. That’s number one, the difficult times of that experience. Number two is my plus-minus, of course.

Mikkelson’s minus-82 mark—in 59 games no less, before the Capitals mercifully spared him with a reassignment to the minors—still stands as the all-time low. (SI’s Michael Farber wrote about Mikkelson, whose daughter won a gold medal with Team Canada at the Vancouver Olympics, in July 2012.)

Low: He gets that record, but the guy was a hell of a defenseman. We just weren’t good enough.

Bill Mikkelson: One of my minuses, I stepped onto the ice and raced to our net, because there were three Montreal Canadiens on our goalie. It was a 3-on-0 and we had a bad change. My other 81 minuses I may deserve, but that one I didn’t.

“I THINK WE DRANK A LOT OF BEER”

Several key members of the original Capitals, like their leading scorer (Williams) and emotional leader (Mohns), are deceased. Other contributors, like Dupéré and Joly, did not reply to interview requests. Marson, who finished as the third-leading scorer with 28 points, declined. “Memories, sometimes, you’ve got to leave them in the past,” forward Gord Smith said, and then did the same as Marson.

Among the dozen who agreed to speak, initial reactions were mixed. “Let’s just say it was not the best year of my life,” began Labre. But many still cling to brief moments of laughter, perhaps even more than any loss. Four-plus decades later, they’re the stories that still act as balms to the sting.

Bruce Cowick, F: Doug Mohns never took his helmet off during the national anthem. He always saluted. There was only one reason: He was completely bald and he didn’t like to show people.

Low: Sometimes he wore a toupee. One night we’re heading off the ice after the period. He takes his helmet off on the way back and his freaking toupee’s stuck in his helmet. Ace goes, “Jesus Christ, don’t let them blow the top of your head off, it’s just a frigging game.”

Bloom: I went with Dupéré and Williams to visit this Air Force colonel who was renting them a really nice house. I remember him saying to Williams and Dupéré, “You guys will take care of my house, right?”

Low: I lived with them. We had a big party at our place. We had a big fireplace and ran out of wood. So Tommy decided to start burning the chairs in our house. Then the next day, guys who didn’t make any money were out buying brand-new chairs for the rented house we had.

Lalonde: The most avid fans were from the Canadian Embassy. They had us down two or three times. They’d have Molson Canadian, a trainload, shipped down to them. It was a little bit of a taste of home in Washington.

Why Lord Stanley never presented his own Cup, more NHL fun facts

Lynch: And in return we’d make sure they had tickets to whatever games they wanted.

Indeed, despite their record, there was excitement in town. Words of encouragement, written onto signs by fans, often hung on the walls of the practice facility. (“Win, lose, or draw we’re behind you,” one said.) Counted upon to engage with locals still learning about the new sport, the Capitals made frequent public appearances, visiting schools or church groups or American Legions or…

Lynch: We were out in Columbia (Md.), halfway between Baltimore and Washington, at a mall trying to promote the team. Kids were coming up, they had no idea what hockey was, no idea who the Washington Capitals were. But air hockey had come out as a popular table game at the time. They thought we were air hockey players.

Labre: They gave me $100 to go to New Carrolton mall and sign some autographs. I was the only one who showed up. There were some kids who were there by accident. I didn’t do too many of those after that. Hockey was going to have a hard time, but the fans we did have were really good fans. That’s proven.

Lesuk: We still hear from a couple fans from over the years. Still get a Christmas card from one family.

Kryskow: They treated us first-class. The only tough times were when they dropped the puck. It wasn’t fun getting your brains beat out.

The coaching switch from Anderson to Sullivan briefly jolted the Capitals, who won the latter’s debut against the Rangers on Feb. 11. The next week, Low posted the franchise’s first shutout victory, 3–0 against Kansas City. But the streak of road losses kept climbing. Their 32nd straight was a particular heartbreaker, 3–1, in Pittsburgh.

Lalonde: So Red comes into the dressing room.

Labre: He told us, “I want everybody up in my hotel room right after you get showered and dressed.” He knew we felt bad enough. He knew the season was halfway done, and he didn’t have to rip us another one.

Lalonde: We all make our way across the street. He’s not there. We’re all sitting around. All of a sudden there’s a knock on the door. This bellboy shows up, and he’s wheeling a cart. He comes in the room, leaves the cart there. Sullivan walks in after, and he says, “Congratulations, boys. You tried hard. Unfortunately we didn’t make it.” He uncovers the cart, and it was two or three cases of beer.

Lynch: For a coach to do that was just unheard of. I thought it was so cool.

Kryskow: I think we drank a lot of beer. That’s all you could do.

“WE GRABBED THE GARBAGE PAIL”

The end was in sight, but the horror season kept claiming victims. After a 14th straight loss, Sullivan stepped aside March 22.

Pyatt: We’re in the dressing room, and I had a towel over my face because I felt so bad for him as he was telling us it was his final game. Red had this raspy voice. You always knew something hilarious was coming down the pipe from him. He says, “You’ve got to admit gang, the only thing you guys set on fire this year was my stomach. I tried to kill it with beer, booze. It just went out, gang.” I felt so bad, but I had the towel over my head and I started laughing.

Left with no choice, Schmidt moved behind the bench. On March 26, the road losing streak hit 37 and the overall slide hit 17 with a 6–3 loss in Los Angeles.

Two nights later, though, salvation arrived. At the Oakland Coliseum, the Capitals scored twice in the opening 4:12, took a 3–1 lead into the first intermission, and rode two late goals from Pyatt, who had recently arrived via trade from Detroit, to a 5–3 win over the Golden Seals.

Pyatt: Someone says, “Hey Nels, this is our big chance tonight.” I’m going, “What? You guys haven’t won a game on the road yet?” I’m thinking, “Holy, man, I’m stepping onto a sinking ship here.”

Lalonde: After we won, we really didn’t know how to react.

Lynch: We grabbed the garbage pail, a Rubbermaid-type pail.

Labre: I wasn’t happy about that. I went, “Oh god.”

Pyatt: We passed it around like we won the Stanley Cup.

Lalonde: We dragged it down the hallway and onto the ice. A couple guys did a couple laps.

Low: When we came back into the room, Ace Bailey got everyone to sign the garbage can.

Lalonde: The next year we go in there, and there’s a garbage can with all of our magic-marker signatures.

Ultimately, the original Capitals exited in style. Behind four goals from Stan Gilbertson, they pounded Pittsburgh in the season finale at home, 8-4. The players stuck around after, signing autographs and snapping pictures and drinking champagne with fans. Some of them reportedly started chanting, “CAPS, WE LOVE YOU,” and “THANK YOU, CAPS! THANK YOU, ABE!”

Ron Weber, radio play-by-play: So it ended the season on a high note… if 8–67–5 can be regarded as high.

“S---, THEY WEREN’T ANY BETTER”

None of the original Capitals remained on the roster when they clinched their first playoff berth, eight years later in 1982-83, which sparked a run of 14 straight postseason appearances. Today, the Capitals are the defending Presidents’ Trophy winners, still searching for the franchise’s first Cup but eons from where they started.

Cowick: For Christmas this year, I wish I could’ve gone back and made it a winning season.

Mikkelson: I wish the current crew there good luck and good fortune. Remind them how lucky they are.

Lalonde: I hear people talking about the worst team in the history of hockey. They ask me, “Oh, you were part of it?” I look back, and I’m proud to say that I played in the NHL, and proud that I played in Washington, and that I was part of the ground floor. Even if it was the worst team in the history of hockey, I wouldn’t trade that for anything in the world.

Pyatt: If I had to do it all over, I’d do it in a New York second. We were just a bunch of young guys trying to make our way.

Mikkelson: How did they do their second year? How’d they do the next year? Eleven wins? That’s all? S---, they weren’t any better.