Mike Ilitch's passion for Detroit and winning endeared him to Red Wings, Tigers fans

Mike Ilitch has died, and the first thing you’ll hear about him was that he wanted to win. Well, we all want to win. What separated Ilitch was how much he wanted to win, and how hard he tried to do it. It was like nothing else mattered. He ran the Red Wings and Tigers the way he lived his life: without a net.

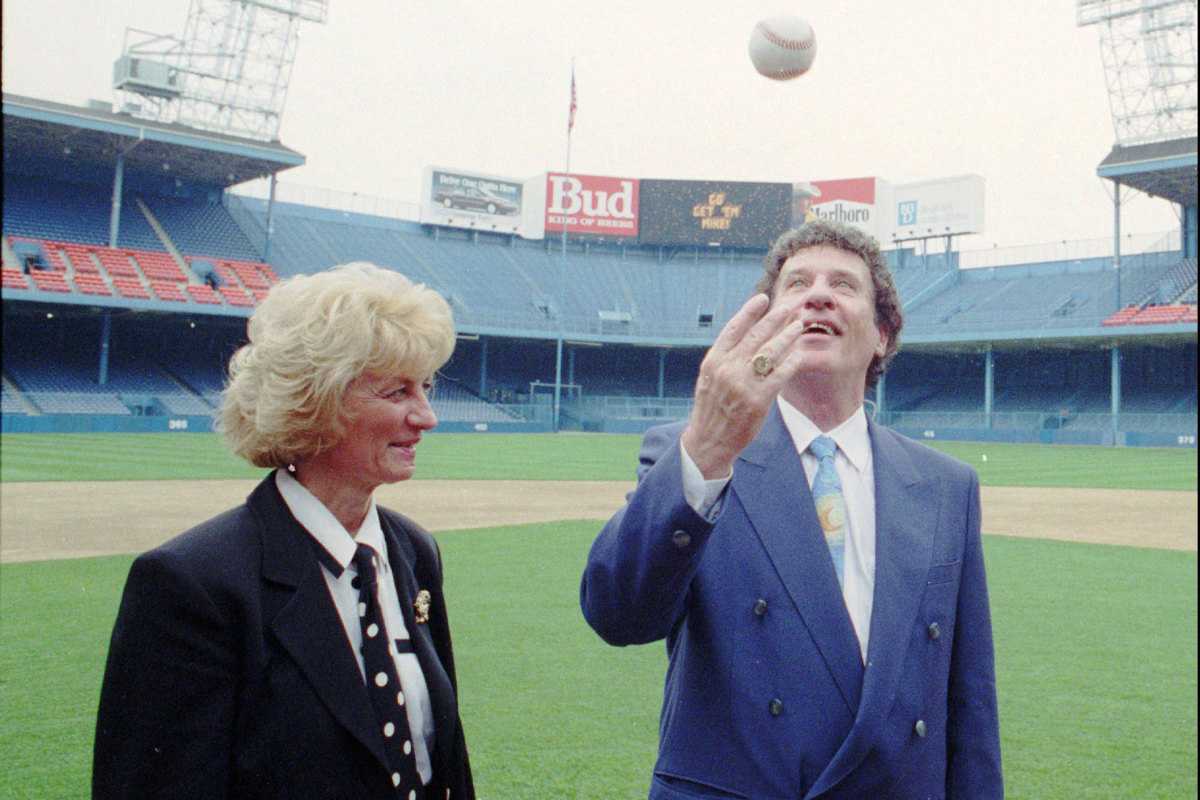

If Ilitch ever worried about risk in his 87 years, he didn’t show it. He was one of the least pragmatic owners in sports history. Marian Ilitch would tell people that when she and her husband started Little Caesar’s Pizza, she worked in the back, in the kitchen, while he was in the front with the customers. But there was a problem. Mike’s friends would show up and he wouldn’t charge them.

It was a theme in Ilitch’s life, again and again: when passion competed against common sense, common sense never had a chance. His heart beat his head every time. The results were extraordinary: four Stanley Cups, two American League pennants, and a record of sustained success in the city of Detroit.

When Ilitch bought the Red Wings, in 1982, they were struggling to attract fans. He gave away a car at every home game. You didn’t even have to buy a ticket to enter the drawing; you could just show up at Joe Louis Arena and put your name in.

Detroit Tigers, Red Wings owner Mike Ilitch dies at age 87

Ilitch later said after giving the cars away he got two thank-you notes—and one guy sued him. But the giveaways were classic Ilitch. There was no business plan behind them. Ilitch said he did it because he “had to do something.” He wanted the city to feel as much passion for the Red Wings as he did.

It must have been fun negotiating with Mike Ilitch. He could never hide his true desires. He would rather get caught eating Domino’s than lose a player he really wanted.

He once told baseball super-agent Scott Boras he would do “whatever it takes” to sign a Boras client. When Tigers designated hitter Victor Martinez tore up his knee one January, Ilitch spent $214 million replacing him. That was the price for Prince Fielder. It was crazy to almost everybody except Ilitch. He did not dwell on price tags. When he saw something he wanted, he bought it.

Reporters could not predict his plans, because they changed on a whim. Some of his own employees were sometimes shocked at how far he would go to improve his team. His tendency to act like the payroll was just Monopoly money could even startle his own family.

In 2001, the Red Wings responded to a rare first-round exit by adding future Hall of Famers Dominik Hasek, and Luc Robitaille. They were far over any reasonable budget, but Ilitch wasn’t done. He signed future Hall of Famer Brett Hull. He did not tell Marian about the negotiations until the deal was done.

Ilitch was a very smart businessman—he didn’t become a billionaire by accident. But when he looked in the mirror, he did not just see his net worth. He really, truly believed he had a role as both private businessman and public servant.

It wasn’t charity work—Ilitch squeezed taxpayers in the building of his new hockey arena, and some people bristled at his habit of holding onto abandoned buildings instead of doing something with the real estate. But look around. Think about Art Modell leaving Cleveland, or the York family banking the revenue from the 49ers’ new stadium instead of pouring it into the team, or James Dolan alienating Knicks fans and former players. In the last decade, especially, Detroit fans would not have traded Ilitch for any other owner.

Ilitch won those four Stanley Cups with the Red Wings, yet he openly admitted: He wanted a World Series title more. As a young man, Ilitch played in the Tigers’ minor-league system; he said a knee injury kept him from reaching the majors.

It took him awhile to figure out how to win in baseball. First he spent too much, then he was too patient with the wrong management team, and finally he hired a great executive, Dave Dombrowski, and he pushed his payrolls near Yankees territory.

And while so many other franchises moved to the suburbs—the Pistons and Lions both operated in the ‘burbs during Ilitch’s tenure—he was committed to the city of Detroit. The Tigers moved from Tiger Stadium to Comerica Park. The Red Wings will move from Joe Louis Arena to Little Caesars Arena in Midtown. When the Pistons were up for sale a few years ago, Ilitch nearly bought them, largely, I believe, so he would have another tenant for the arena he wanted built for the Wings.

He needed whatever leverage he could find. Everybody knew he would never move the Wings out of the city. He also restored the Fox Theater in Detroit. All this arena-building may not seem like a big deal in other cities. But Detroit was a city in terrible decline until the last few years. Ilitch was a bulwark at a time when Detroit desperately needed one. No, he did not win that World Series. But he made it clear he would win or die trying, and that’s a hell of a way to live a life.