In Hockey, ‘If You Saw It, You Missed It’

Full Frame is Sports Illustrated’s exclusive newsletter for subscribers. Coming to your inbox weekly, it highlights the stories and personalities behind some of SI’s photography.

To get the best of SI in your inbox every weekday, sign up here. To see even more from SI's photographers, follow @sifullframe on Instagram and visit SI.com/photos. If you missed last week’s edition on shooting Dak Prescott and his scars, you can find it here.

There was no easing David E. Klutho in when he first started photographing for Sports Illustrated on March 1, 1986. His first assignment was an NHL game, a 6–3 home win for the Blues over the Blackhawks.

Just two months later, Klutho was thrown into the deep end. When it got to the conference finals of the Stanley Cup playoffs, the NHL staggered games every day. That meant Klutho would cover Rangers-Canadiens one night and Blues-Flames the next.

“I did both conference final series, all games,” he says. For example, he would cover a game in Calgary at night, then fly to New York the next morning to get to Madison Square Garden for that night’s game.

When he covered that year’s Cup finals he again photographed every game in both cities (Montreal and Calgary).

In a way, that first spring for Klutho photographing for SI set a precedent. Klutho would go on to cover 33 straight Stanley Cup finals from 1986 to 2019 (the finals weren’t played in ’05 due to a lockout.)

One of the biggest changes Klutho says he’s seen over his years covering hockey is in how the Stanley Cup is celebrated by the winning franchise.

“There were no stages, hats, T-shirts,” Klutho says, thinking back to 1986. “There’s none of that. I don’t even know if there were ads on the boards. That was real hockey.”

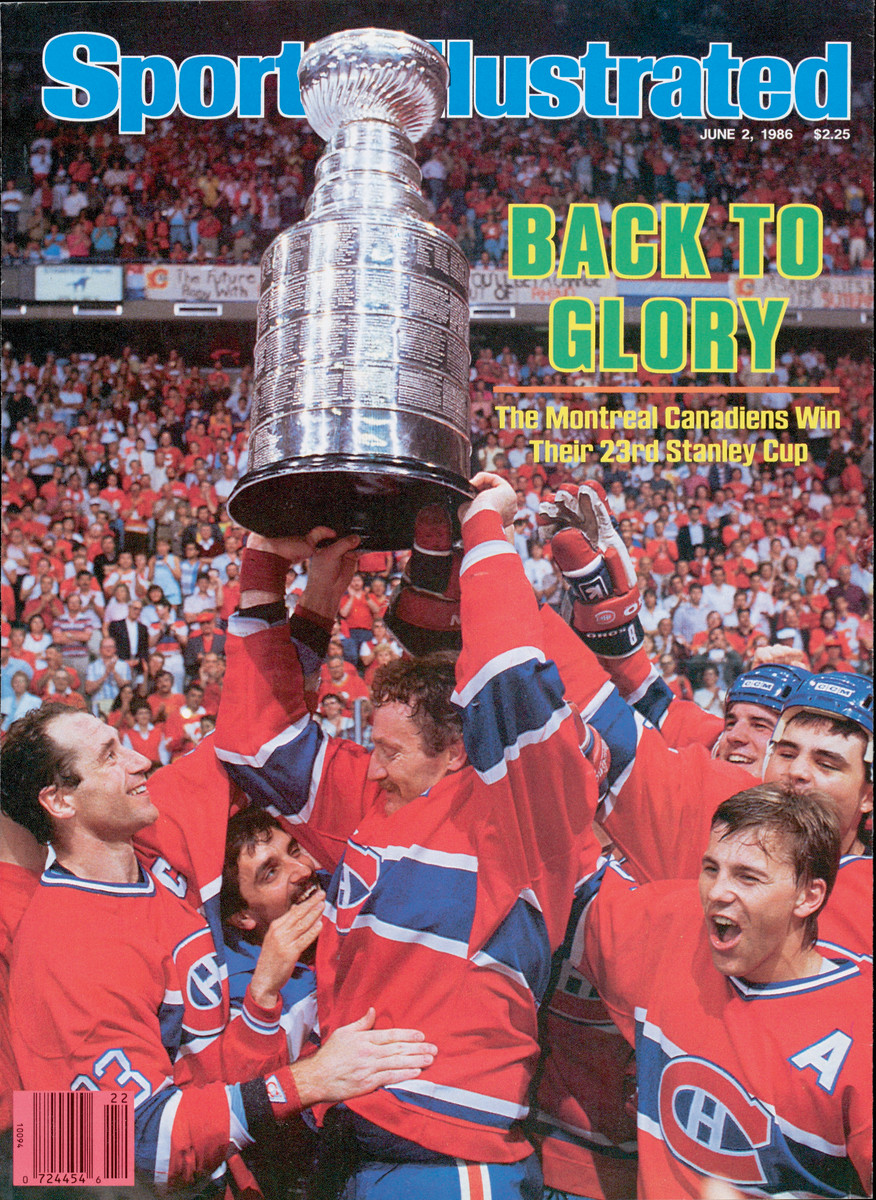

Klutho captured the image that ended up going on the cover of the June 2, 1986, issue of SI, with the Habs’ celebrating their 23rd Stanley Cup.

“They were bumping into me, and I had to jump back. You just went out there and did your job. Now there’s so many restrictions, and TV gets this and NHL Images gets this. Everyone puts on the hats. The amazing thing is that the game ends and there’s a little celebration when they mob the goalie or whatever. Then they’re just standing around. It’s the most boring thing you’ve ever seen because they’re waiting for people to set up things. You really miss the real celebration and energy of it. Back in the day, they gave the Cup right away. That’s when all those guys skated around with it traditionally,” Klutho says.

But while the celebrations have taken a decidedly different feel over the years, covering games remains a puzzle for any photographer. “It’s the most challenging sport to shoot,” Klutho says.

“It’s not like basketball,” he adds. “If Michael Jordan is going to dunk, you know where that’s happening. In hockey, the best pictures aren’t usually of the goalie.”

The first challenge is the limited vantage points. When you’re sticking your camera lens through a hole in the rink (“or, even worse, you’re shooting through the glass itself,” Klutho says) you can’t swing your camera to get different angles of the action on the ice.

That forced him to get creative. At the 1991 NCAA men’s ice hockey championships in St. Paul, Minn, the boards surrounding the rink were plexiglass and clear down to a bright yellow band just above the ice. Klutho convinced the NCAA to let him cut a hole in the boards inside the goal line. He then laid on his stomach under the stands to shoot through his makeshift hole.

In Detroit, SI cut a hole behind the net and off to one side at a zamboni entrance, which Klutho used for a number of years during the Red Wings’ string of success during the 1990s and early 2000s.

The second factor involved the mechanics of shooting the sport. Until 2003, Klutho and SI shot film. So, not only did he have to manually focus and zoom, but Klutho shot using strobes and single frames. Strobe lights would be set up in the stadium to mimic the arena’s lighting, but with much more light. They all went off at the same time and lit the entire building, enabling photographers to move around and still have the same light.

“When you shot film in the low-light levels of some arenas,” Klutho says, “it would be just nasty looking. At the stadiums with good strobe systems, my god, it looks night and day. If you look through some old SIs, you’ll see it’s so sharp.”

Though the strobes created sharp images, it took about three seconds for the lights to recycle. Compare that to the digital cameras used today, where you can capture split-second frames and entire sequences of play, and it’s almost like an entirely different discipline, where you “lose sight of timing and composition,” he says.

“Once I started doing this regularly, especially hockey, I would find myself shooting automatically,” Klutho says. “It’s not even crossing my mind to shoot the picture. It’s the weirdest thing. The best thing I can compare it to is when you’re driving along on a highway and you’re in your car and 10 miles later you just say, Oh my god, I wasn’t paying attention. But you’ve been making all these turns.”

“That’s what makes you be able to get things better,” he adds. “If you saw it, you missed it.”