‘What a Scene’: How a Canadian Expat’s Seattle Bar Became the Heart of Kraken Nation

ATOP A BARSTOOL INSIDE THE ANGRY BEAVER—When Tim Pipes arrived for work one afternoon five years ago, one of his employees told him someone named Todd had called. He asked for the caller’s last name, and when the employee said it started L-E-I, Pipes burst out laughing. This wasn’t some random Todd. This was Tod Leiweke, CEO of Seattle’s new hockey team, calling the city’s first—and, at that point, only—hockey bar.

A few weeks later, on Feb. 28, 2018, Leiweke stopped in for a pint. Pipes remembers the exact date because, the next day, someone bought the first Kraken ticket. Someones, actually, as more than 30,000 were immediately scooped up. At the bar, Leiweke asked Pipes whether he thought the team could sell 10,000 season packages in the first hour. “Five minutes,” Pipes responded.

Leiweke motioned to a friend at his table and said, “Come over and tell Jerry this.”

This wasn’t some random Jerry, either. This was Jerry Bruckheimer, the iconic filmmaker, who smiled at Pipes—the man from Toronto whose life had wound to Seattle, where he went looking for a place to watch his beloved Maple Leafs and came up empty.

What Pipes knew then, what he believed deep down, is now obvious, from new rinks to merchandise sales to one of the youngest and most entertaining teams in the NHL. The city had something of a hockey section in its soul. He built the bar to bolster and tether it. They came. And now, on this Sunday in May, as the Kraken face the Stars in the second round of the NHL playoffs, locals consider The Angry Beaver the equivalent of Pipes’s rink of hockey dreams. It’s loud, packed, indicative, magical. But that’s not even half the story.

I called Pipes hoping he would watch Sunday’s Game 3 with me, at the bar, surrounded by his customers and the significance of what he did, the toll exacted, the payoff happening, in some ways in real time. At first, he declined when we spoke last Friday. He had PTSD symptoms, he explained, and avoided crowds, even ones that paid him. But after talking—about his bar, his adopted city and its burgeoning hockey obsession—he reconsidered.

“I’m gonna meet you there,” he said, just before hanging up, promising tequila shots.

With 20 minutes left before the start of Game 3, hockey fans of all ages, ethnicities and origins pack into The Angry Beaver. The line to order drinks extends from the bar to the back wall. The distinct smell of cannabis wafts through the open windows from outside, as a Kraken-centric crowd filters into something like hockey heaven.

Pipes sits at the end of the bar, surrounded by an overwhelming amount of memorabilia. Much of the jerseys, pennants, bobbleheads, street signs and newspaper articles were donated by hockey fans who love the vibe. There’s hardly an inch of open wall space left. Special jerseys, signed and framed, hang between the bar area and restaurant space, while the wall opposite the bar is a collage of jerseys: hockey uniforms as artwork, more or less.

There’s an autograph from The Great One, Wayne Gretzky, procured as a trade for drinks and food (and not with Gretzky). And a signature from Capitals winger T.J. Oshie, whose father, Tim, has stopped by and drank whiskey with Pipes. And donated pennants from obscure or older hockey teams (Atlanta Flames, Vancouver Blazers, Kansas City Scouts). And a baseball tucked inside the display case near the entrance. It’s signed, ostensibly, by Bobby Orr, Gordie Howe, Brad Park and Phil Esposito—hockey legends, all. If the scribbles are authentic, the ball is quite valuable. But that’s not the point, for the man, his bar or anyone who managed to wiggle inside Sunday night.

Most are there for the atmosphere, to imbibe and cheer on the Kraken. With the series tied at 1, the hockey team in coffee country with a sea monster for a mascot continues to surprise. The Stars entered the Western Conference semifinals as heavy favorites. Dallas was still -210 to win the series before the game started, and many expected the Stars to reach, if not win, the conference finals. Their 108 points this season ranked fourth in the conference, behind only Colorado (ousted by the Kraken in the first round), Las Vegas and Edmonton. Dallas finished the regular season on an 8–2 run.

Away from The Angry Beaver, more believe the Kraken will lose this series than believe they will pull together another seismic upset. But inside? They’re saying there’s a chance!

As the first period unfolds without a score, a man saddles up to the bar. He is wearing a Kraken jersey and orders two beers and a shot. I ask for a few details. His name is Peter Roberts. He’s 47. He seems happy and immediately reveals the reason for his joy. He lives about 20 minutes north, in Lynnwood, has children and hardly ever gets out. Tonight, though, his first away in forever, he took an Uber here. He loves hockey and still plays and figured The Angry Beaver was made for people just like him. Pipes smiles and introduces himself. Roberts is spot on.

“First time,” he says. “What a scene.”

Watch the Kraken with fuboTV. Start your free trial today.

Sometimes, even through the glorious stretches, Pipes feels sort of … cursed. He knew owning and operating a bar, in a city where growth equates to perpetual inflation and an industry where more fail than succeed, would be difficult. But what happened, to him and his bar, makes difficult seem easy in comparison.

Pipes opened the space in 2012. In the 11 years since, he lost his mother and his father. He got divorced. His finances shrunk, while his health declined. Rent went up, and up. And up again. The bar closed during the COVID-19 pandemic. His ailing back required a pair of surgeries. And all of that paled when considering …

On March 9, 2016, NHL hockey in Seattle was but a Pipes dream. He sat inside his bar early that morning, listening to his now-ex-wife complain about the lack of customers. “Closing time is only another half hour away,” he said.

At 1 a.m., they packed up and locked the doors. Then, suddenly, they heard what sounded like an explosion—and it was close. Heard isn’t exactly right. They felt it. “I swear to God, I thought it was a terrorist attack,” Pipes says.

The next sound Pipes describes was even scarier, if that’s possible. Like air being vacuumed into the cosmos. When Pipes turned to his left, he saw a ball of fire, maybe 50 feet wide, barreling right at him, only to, thankfully, halt or misdirect before it could torch his body in addition to the bar. The damage nearly destroyed his hockey experiment. Smashed windows. Broken bottles of booze. Artwork sent flying off the walls. The blast even pushed his facade in maybe four or five inches.

He screamed at everyone within earshot. “Get the f--- out of the bar!” But then he worried that he sort of remembered someone being in the bathroom when the blast hit. He sprinted back inside, pushed open the restroom doors and, thank God, saw only empty stalls. As far as good news went, though, that was it. “I couldn’t believe what I was looking at,” he says. “Mind-blowing.”

The three businesses directly across Greenwood Avenue North were no longer businesses. Wiped off the face of the earth. They’re still no more than an empty lot marked for upcoming construction.

His bar looked like a bomb site. Opening it, building something, marked one of the highlights of Pipes’s life. He arrived in Seattle back in 1991, as a musician and Berklee College of Music graduate drawn to an epic, grunge-heavy music scene. He played in a band called Bananafish, a five-piece, four-part harmony with The Beatles or Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young vibes. They made it pretty far, too, opening once for Heart and Queen at The Gorge Amphitheater, the state’s primo music venue. Pipes always thought that day would mark the most memorable of his life, until the bar opened, thanks to a smart (and early) investment in Apple. Then he thought the opening might be, until the bar was nearly destroyed by the explosion.

Soon after, thieves broke in, snapping the flimsy deadbolt on the kitchen entrance. Boards still covered where the windows had been; the robbery was that close to the blast. They stole liquor and cash, damaged stereo equipment and broke the nonalcoholic bottles. Pipes received a phone call the next morning, summoning him. Upon arrival, he sat on a milk crate in the back and, he says, “I literally broke down. Completely lost my s---.” He had already dealt with the NHL lockout during his first year as a bar owner. His insurance quadrupled, while he paid his employees when he could no longer open and his landlord still charged rent. Turns out, the explosion started with a natural gas leak in the neighborhood. He couldn’t reopen for nearly four months.

Then, everything else. Then, Leiweke, the Kraken, the debut season, this season and the playoffs. Rent continued to climb. Inflation went bananas. This was 11 lifetimes in 11 years. But through it all, his main aim—to build camaraderie and community through hockey —never changed.

Pipes considered closing. He almost had to shutter this place that meant so much to so many, and more than one time. Eventually, he resolved to stay open, no matter the costs, whether personal or professional or to his well-being.

The Angry Beaver is both distinctly Seattle and unabashedly Canadian. Maybe I’m wrong but that has to be a combination of one in these parts.

It’s tucked into a neighborhood located north of downtown that retains the vibe of Seattle before the tech boom. Downtown is high rises and towering office buildings and experiments in automated grocery stores. Greenwood isn’t that, or the suburbs to the east; it’s a more gritty vibe, with independent and small businesses, older homes and cooler dive bars. The Angry Beaver fits that well. It also serves poutine and a Canadian-style Bloody Mary—the Bloody Caesar, made with clam juice subbed for tomato. Pipes celebrates Canada Day and shows hockey on all seven of his flatscreens. He held a moment of silence for the junior hockey players who died in the Humboldt bus crash a few years back.

For Olympic gold-medal games, he has opened at 3 a.m. when Canada isn’t playing. He serves only coffee, water and soft drinks, but features live “Oh, Canada” renditions for packed houses. Born in Winnipeg and raised in Toronto, Pipes’s blood type is a mixture of mullets, poutine and ice skates. Once, a women’s gold-medal game nearly brought him to tears. The scene that morning marked yet another reminder, perhaps the most significant yet: he had been right about hockey in Seattle all along.

His PTSD symptoms started after the explosion. Large, rowdy crowds, like the ones that pack his bar for Kraken playoff games, can make Pipes “a little shaky.” Still, it’s not like he wants an empty space. To combat the toll the explosion exacted, he took an anti-anxiety pill before driving in for Sunday’s game and ordered those tequila shots during the first period. Surveying the scene, he says, “This is why I built the bar.”

After the blast and the robbery, Pipes and his staff fixed everything. They polished and deep-cleaned the renovated space and added a pool table. The Angry Beaver continued to show hockey of all types—World Cups, juniors, Olympics, NHL contests and whatever else might come on. Pipes believed he owed his customers the vibe they sought, a place for their hockey souls. That’s why they packed in The Angry Beaver in the first place and why they mounted a fundraising campaign to help him cover repairs and operating costs.

Under the events tab on the bar’s website, Kraken playoff games aren’t listed. There’s no need. They are events, of course. But here, they are also Sunday.

The regulars and newbies and the I-had-no-ideas came for Game 1 against Dallas, for the upset few believed possible. The Kraken won, on the road, on an overtime goal from Yanni Gourde. Victory even meant a slice of NHL history, as Seattle netted three goals in 52 seconds in the first period—the sixth-fastest trio of scores by one team in NHL postseason history.

Dallas reasserted its dominance relative to expectations in Game 2, making adjustments and finding balance from its stars, and won easily, 4–2. The series would switch to Seattle for portending potential doom. Of course, that wasn’t so, as evidenced by the scene at The Angry Beaver on Sunday night.

The hockey heads clustered inside cheered, boisterously and often. They cheered for the first-period fight that got broken up. Cheered when the best Kraken players skated into view. Cheered when the poutine flights arrived at their tables covered in three types of gravy.

But consider all that mere prelude to the madness yet to come.

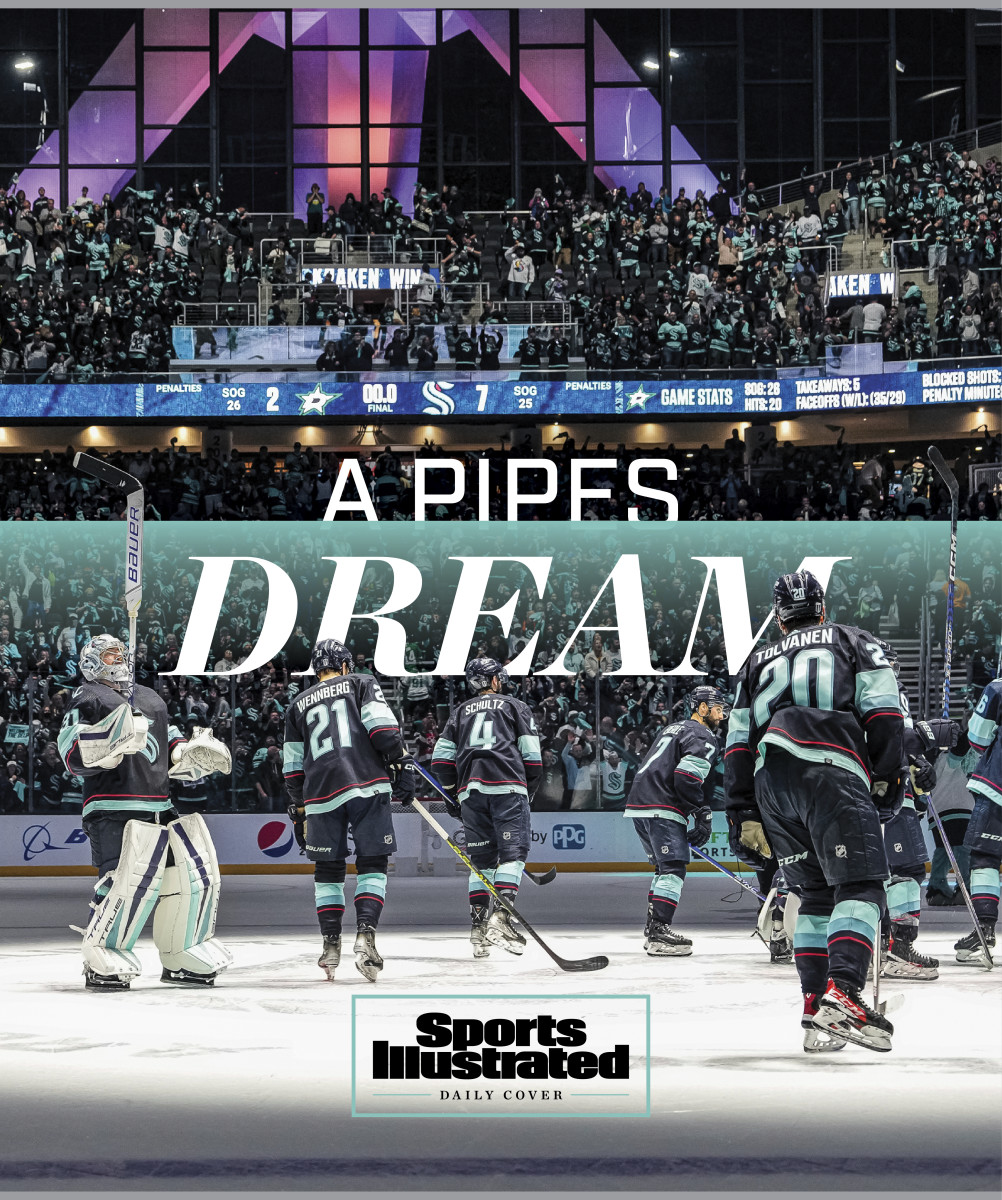

The Kraken did not take control in the second period so much as they obliterated the notion that the series had already slipped from their collective grasp, that they would not win another game. They scored at the 2:10 mark (Jordan Eberle), again 76 seconds later (Alex Wennberg) and yet again not even three minutes after that (Carson Soucy). Seattle netted five goals in that period alone, along with two more in the third period.

Owing to the day and time (Sunday, late evening and night), the bar wasn’t as packed as it would normally be for Kraken playoff hockey. Still, between the atmosphere, drinks and goal barrage, it was loud enough that my ears were ringing 90 minutes after leaving. There were “Let’s go, Kraken” chants. There was trash talk levied to the brave Stars fans who showed up. There were more tequila shots. A Sunday Funday had broken out.

How many in attendance remembered the final score (7–2) Monday back at their office cubicles? Not many is the bet here, which, again, isn’t the point. The point is Roberts, who stopped back at the bar for another round late in the game. He asked about my laptop, how I could write inside a bar (answer: practice, failure, more practice). This opened a window to dig deeper into his backstory. Roberts wasn’t just a middle-aged dad from the suburbs finding a rare night of bliss. His wife had died six months ago. Cancer. She had been in treatment the past couple of years. He had purchased season tickets and been to only six games in the Kraken’s two seasons. This marked some of his first free hours since her death.

I told Pipes this story a little later, when he sat back down. We both fought back tears, the moment powerful and instructive. He didn’t create this bar for Roberts, not exactly. But he also did. He created the bar for people who love hockey, and, while some might stop in for the beer and others for the poutine and still others to watch their favorite teams, some also come for an escape that can mean much more.

As the Kraken morphed from one of the season’s largest surprises into a legitimate playoff force, patrons told Pipes he “deserved this,” after everything. But that’s not right. Not exactly. The playoff run and its corresponding economic impact are critical to The Angry Beaver. But don’t mistake that as tied to the hell Pipes has lived through the past decade-plus. He created hockey heaven. He lived through regular-life hell. Both exist, but not in relation to each other. He doesn’t “deserve this” for the robbery, the explosion, the pandemic or anything else, Pipes says.

Instead, the takeaway is actually purer, more poetic. Pipes deserves this the same as his patrons deserve this. Because hockey matters in Seattle—and because it did long before the Kraken existed, let alone made the playoffs, won a series or embarked on a glorious run. By 8:20 p.m., the bar was raucous. Patrons continued to stream in. The Angry Beaver felt more like the epicenter of hockey in Seattle than Climate Pledge Arena, no disrespect intended. Why? Soul.

“Just as human beings, there’s been this massive underlying part of it,” Pipes says. “I didn’t know anything about running a bar/restaurant. But I figured it out.” He flashes backward to Game 7 of the first round, when The Angry Beaver was so jammed another human being could not have fit inside. The contest went to overtime. The bar went silent. When the Kraken won, well … it’s hard for Pipes to explain. “Just tears popping out of my eyes,” he says.

He pauses, like he’s trying to calculate how all the events from the past 11 years—11 lifetimes—make sense. “Without a doubt the hardest thing I’ve ever done by a long shot, miles and miles,” he says. “I’ve lost so many people, employed so many, served so many. But now, people are walking into the place, thanking me, saying what it means to them.”

Soon, Pipes will lament the end of the playoffs. But, in many ways, he’s like the original Starbucks, a part of Seattle that hardly exists anymore but matters, more than ever, as everything else changes. Yup, soul. He’s a destination, an experience. The Angry Beaver is where people go for exactly what Pipes created. It’s older, stuffed to the ceiling with dive-bar character, a home for wayward hockey souls.

Which reminds him of that first call with Leiweke. When “Todd” dialed The Angry Beaver, he told the employee who answered, “We’re down in Georgia. We just got a hockey club. Tell Tim to buckle up.” Pipes considers the path from there to here, leading to another, inevitable pause. And then …

“Man, I love this part.”